Czesław Miłosz facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Czesław Miłosz

|

|

|---|---|

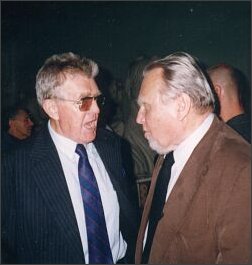

Miłosz in 1999

|

|

| Born | 30 June 1911 Šeteniai, Kovno Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Died | 14 August 2004 (aged 93) Kraków, Poland |

| Occupation |

|

| Citizenship |

|

| Notable works | Rescue (1945) The Captive Mind (1953) A Treatise on Poetry (1957) |

| Notable awards | Neustadt International Prize for Literature (1978) Nobel Prize in Literature (1980) National Medal of Arts (1989) Order of the White Eagle (1994) Nike Award (1998) |

| Spouse |

Janina Dłuska

(m. 1956; died 1986)Carol Thigpen

(m. 1992; died 2002) |

| Children | Anthony (born 1947) John Peter (born 1951) |

| Signature | |

Czesław Miłosz (born June 30, 1911 – died August 14, 2004) was a famous Polish-American poet, writer, translator, and diplomat. Many people consider him one of the greatest poets of the 20th century. He won the 1980 Nobel Prize in Literature. The Swedish Academy, which gives out the Nobel Prize, said Miłosz was a writer who "voices man's exposed condition in a world of severe conflicts." This means he wrote about how people feel when they face tough times.

Miłosz lived through the German occupation of Warsaw during World War II. After the war, he worked for the Polish government as a cultural attaché. This job involved promoting Polish culture. When the communist government in Poland became too dangerous, he moved to France. Later, he chose to live in the United States. There, he became a professor at the University of California, Berkeley.

His poems, especially those about his wartime experiences, became very well known. He also wrote a book called The Captive Mind. This book looked closely at Stalinism, a harsh form of communism. These works made him famous as a leading artist and thinker who had left his home country.

Throughout his life, Miłosz wrote about important ideas. These included questions about right and wrong, politics, history, and faith. As a translator, he helped Polish readers discover books from Western countries. As a scholar, he helped people in the West learn more about Slavic literature. His Catholicism and personal experiences also influenced his writing. He wrote in both Polish and English.

Miłosz passed away in Kraków, Poland, in 2004. He is buried in Skałka, a church in Poland where many important Poles are honored.

Contents

Life in Europe: Growing Up and War Years

Early Life and Family History

Czesław Miłosz was born on June 30, 1911. His birthplace was the village of Šeteniai in what was then the Russian Empire. Today, this area is part of Lithuania. His father, Aleksander Miłosz, was a Polish civil engineer. His mother, Weronika, came from a well-known Polish family.

Miłosz's family had a long history. His mother's family could be traced back to the 13th century. His grandmother's ancestor was a personal secretary to a Polish king. His paternal grandfather fought for Polish independence in 1863. Even with this noble background, Miłosz's childhood was not fancy. He wrote about his early life in books like The Issa Valley and Native Realm. He described how his Catholic grandmother influenced him. He also shared his early love for books and his thoughts on social classes.

Miłosz's early years were full of changes. His father worked on projects in Siberia, and the family traveled with him. When World War I started in 1914, his father joined the Russian army. Miłosz and his mother moved around a lot. They were in Vilnius when the German army took it over. They also followed his father deeper into Russia. His brother, Andrzej, was born in 1917. The family finally returned to Šeteniai in 1918.

But the Polish–Soviet War began in 1919. Miłosz's father tried to join Lithuania with Poland. This failed, and the family had to move to Wilno, which was then under Polish control. The war continued, forcing them to move again. Miłosz even wrote about Polish soldiers shooting at him and his mother. The family returned to Wilno after the war ended in 1921.

Education and Early Writings

Despite all the moving, Miłosz was a great student. He was very good at learning languages. He learned Polish, Lithuanian, Russian, English, French, and Hebrew. After high school, he studied law at Stefan Batory University in 1929. At university, he joined student groups for intellectuals and poets. His first poems were published in the university's student magazine in 1930.

In 1931, he visited Paris and met his distant cousin, Oscar Milosz. Oscar was a French poet and became a mentor to Czesław. Back in Wilno, Miłosz stood up for Jewish students. They were being bothered by an anti-Semitic mob. He stepped between the mob and the students, even though it was dangerous.

Miłosz's first book of poems, A Poem on Frozen Time, came out in 1933. That same year, he read his poems at an anti-racist event. This was because Adolf Hitler was gaining power in Germany. In 1934, he finished his law degree. He then moved to Paris for a year on a scholarship. He wrote articles for a newspaper and often met with his cousin Oscar.

By 1936, he was back in Wilno. He worked at Polish Radio Wilno, creating literary programs. His second poetry book, Three Winters, was published that year. Some critics compared him to the famous poet Adam Mickiewicz. After a year, he was fired from Radio Wilno. Some people thought he was a left-wing supporter. He had adopted socialist ideas as a student, though he later moved away from them. He and his boss had also included Jewish and Byelorussian performers, which angered some right-wing groups. In 1937, Miłosz moved to Warsaw. He found work at Polskie Radio and met Janina Dłuska, who would become his wife.

World War II Experiences

Miłosz was in Warsaw when Germany invaded Poland in September 1939. He escaped the city with colleagues but returned to find Janina. The Soviet invasion of Poland made his journey difficult. He had to get fake documents and travel mostly on foot. He finally reunited with Janina in Warsaw in 1940.

To avoid German authorities, Miłosz joined underground activities. He attended secret lectures, as higher education was forbidden for Poles. He translated famous works like Shakespeare's As You Like It and T. S. Eliot's The Waste Land. He also published his third poetry book, Poems, secretly in 1940. It was published under a fake name and press. In 1942, he helped publish an anthology of Polish war poetry.

Miłosz took big risks to help Jews in Warsaw. He worked with an underground group called Freedom. His brother, Andrzej, also helped Jews. Miłosz took in a Jewish couple, the Trosses, and helped them hide and gave them money. They sadly died during the Warsaw Uprising. He also helped at least three other Jewish people.

Miłosz did not join the Polish Home Army. He later said this was partly to protect himself. He also felt their leaders were too strict. He did not take part in the Warsaw Uprising. He thought it was a "doomed military effort." He later criticized the Red Army for not helping the uprising.

In August 1944, German troops began burning Warsaw. Miłosz was captured and held in a camp. A Catholic nun, a stranger, helped him escape. He and Janina fled the city. They settled in a village near Kraków. They were there when the Red Army entered Poland in January 1945. Warsaw had been mostly destroyed.

After the war, Miłosz published his fourth poetry collection, Rescue. It focused on his wartime experiences. This book includes some of his most famous poems. These include "A Song on the End of the World" and "Campo Dei Fiori."

Working for Poland and Leaving Communism

From 1945 to 1951, Miłosz worked as a cultural attaché for the new People's Republic of Poland. He lived in New York City, Washington, D.C., and Paris. His job was to organize and promote Polish cultural events. Even though he represented Poland, which was a Soviet-controlled country, he was not a communist. He did not publish books during this time. Instead, he wrote articles about American writers for Polish magazines. He also translated works by Shakespeare and others into Polish.

In 1947, his son, Anthony, was born in Washington, D.C.

In 1948, Miłosz helped set up a Polish Studies Department at Columbia University. This department was named after Adam Mickiewicz. However, some Polish groups in the U.S. thought it was a communist plot. They protested, but the department was still created. It closed in 1954 when Poland stopped funding it.

In 1949, Miłosz visited Poland again. He was shocked by the fear he saw everywhere. He started looking for a way to leave his job. He even asked Albert Einstein for advice.

The Polish government, influenced by Joseph Stalin, became more controlling. They saw Miłosz as a threat because he spoke his mind. In late 1950, his passport was taken away. He was told it was to check if he planned to leave the country. After some help, he got his passport back. Realizing he was in danger, Miłosz left for Paris in January 1951.

Seeking Asylum in France

When Miłosz arrived in Paris, he went into hiding. He was helped by a Polish magazine called Kultura. His wife and son were still in the U.S. He tried to enter the U.S. but was denied. At that time, the U.S. was in a period called McCarthyism. Powerful Polish groups had convinced American officials that Miłosz was a communist. He could not leave France. His second son, John Peter, was born in Washington, D.C., in 1951, and Miłosz was not there.

Since the U.S. was closed to him, Miłosz asked for political asylum in France, and it was granted. After three months in hiding, he announced his decision to leave the Polish government. He explained his reasons in a Kultura article called "No". He was the first important artist from a communist country to publicly explain why he broke ties with his government. His case got a lot of attention. His work was banned in Poland. Some people criticized him, like the poet Pablo Neruda. But others, like Albert Camus, supported him.

Miłosz was finally reunited with his family in 1953. Janina and their children joined him in France. That same year, he published The Captive Mind. This book explained how Soviet communism worked and its effects. It helped many people in the West change their minds about communism. The German philosopher Karl Jaspers called it an "important historical document." It became a classic book for studying totalitarianism.

Miłosz wrote a lot during his years in France. He published two poetry books, Daylight (1954) and A Treatise on Poetry (1957). He also wrote two novels, The Seizure of Power (1955) and The Issa Valley (1955). His memoir, Native Realm (1959), also came out. All these were published in Polish by a press in Paris.

A Treatise on Poetry is considered one of Miłosz's most important works. It is a long poem that looks at Polish history. It also tells about Miłosz's war experiences and how art and history are connected.

In 1956, Miłosz and Janina got married.

Life in the United States: Teaching and Nobel Prize

Becoming a Professor in California

In 1960, Miłosz was offered a job at the University of California, Berkeley. This allowed him to move to the United States. He was a very good and popular teacher. He was given a permanent teaching position after only two months. This was unusual because he did not have a PhD or much teaching experience. But his deep knowledge was clear. After years of administrative jobs he didn't like, he felt at home in the classroom. With a steady job as a professor of Slavic languages and literatures, Miłosz became an American citizen. He also bought a home in Berkeley.

Miłosz started writing scholarly articles in English and Polish. He wrote about authors like Fyodor Dostoyevsky. But he felt a bit lonely in his early years at Berkeley. He was seen more as a political figure than a great poet. Many of his colleagues didn't even know he wrote poetry.

To help Americans discover his poetry, Miłosz put together an anthology. It was called Postwar Polish Poetry and was published in English in 1965. This book had a big impact. It was the first time many English readers saw Miłosz's poems. It also introduced them to other Polish poets like Wisława Szymborska. In 1969, his textbook The History of Polish Literature was published in English. He then released his own book, Selected Poems (1973). He translated some of these poems himself.

At the same time, Miłosz kept publishing in Polish. His poetry collections from this period include King Popiel and Other Poems (1962) and From the Rising of the Sun (1974).

During Miłosz's time at Berkeley, the campus was a center for student protests. He sometimes disagreed with the student protesters. He called them "spoiled children" and thought their political passion was naive. He felt they didn't understand real hardship.

After 18 years, Miłosz retired from teaching in 1978. He received a special award from the University of California. But when his wife, Janina, became ill, he returned to teaching seminars to help with medical costs.

Winning the Nobel Prize

On October 9, 1980, the Swedish Academy announced that Miłosz had won the Nobel Prize in Literature. This award made him famous around the world. On the day the prize was announced, Miłosz held a short press conference. Then, he went to teach his class on Dostoevsky. In his Nobel lecture, Miłosz spoke about the role of a poet. He also talked about the sad events of the 20th century. He honored his cousin Oscar.

Many Poles learned about Miłosz for the first time when he won the Nobel Prize. His writing had been banned in Poland for 30 years. After the prize, some of his works were finally published there. He also visited Poland for the first time since 1951. Crowds greeted him like a hero. He met important Polish figures like Lech Wałęsa and Pope John Paul II. At the same time, his early Polish works were translated into English and many other languages.

In 1981, Miłosz was invited to give lectures at Harvard University. He used this chance to highlight writers who had been unfairly imprisoned. These lectures were published as The Witness of Poetry (1983).

Miłosz continued to publish new works. These included poetry collections like Hymn of the Pearl (1981) and Unattainable Earth (1986).

In 1986, Miłosz's wife, Janina, passed away.

In 1988, his Collected Poems came out in English. After communism fell in Poland, he divided his time between Berkeley and Kraków. He started publishing his Polish writings with a publisher in Kraków. When Lithuania became free from the Soviet Union in 1991, Miłosz visited for the first time since 1939. In 2000, he moved to Kraków permanently.

In 1992, Miłosz married Carol Thigpen. She was a professor at Emory University. They were married until her death in 2002. His later works include poetry collections like Facing the River (1994) and Roadside Dog (1997). His last poetry books were This (2000) and The Second Space (2002).

Death and Legacy

Czesław Miłosz died on August 14, 2004, at his home in Kraków. He was 93 years old. He had a state funeral at the historic Mariacki Church in Kraków. Important people like the Polish Prime Minister and former president Lech Wałęsa attended. Thousands of people watched as his coffin was moved to his final resting place at Skałka Roman Catholic Church. Poets read his poem "In Szetejnie" in many languages he knew.

Some protesters tried to disrupt the funeral. They claimed Miłosz was anti-Polish or anti-Catholic. But Pope John Paul II and Miłosz's confessor (a priest he spoke to) publicly confirmed that Miłosz had received religious rites. This helped calm the protest.

Family Members

Miłosz's brother, Andrzej Miłosz (1917–2002), was a Polish journalist and translator. He made documentaries about his brother.

Miłosz's son, Anthony, is a composer and software designer. He has translated some of his father's poems into English.

Awards and Honors

Besides the Nobel Prize, Miłosz received many other awards:

- Polish PEN Translation Prize (1974)

- Neustadt International Prize for Literature (1978)

- National Medal of Arts (United States, 1989)

- Order of the White Eagle (Poland, 1994)

He was also a visiting professor at many universities. He received honorary doctorates from places like Harvard University and the University of California at Berkeley. Some academic centers are named after him.

In 1992, Miłosz became an honorary citizen of Lithuania. His birthplace was turned into a museum. In 1993, he became an honorary citizen of Kraków.

His books also won awards. His first book, A Poem on Frozen Time, won an award from Polish writers. The Seizure of Power received the European Literary Prize. His collection Roadside Dog won a Nike Award in Poland.

In 1989, Miłosz was named one of the "Righteous Among the Nations" at Israel's Yad Vashem memorial. This was to honor his efforts to save Jews during World War II.

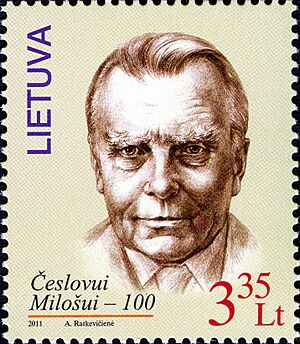

Miłosz has been honored even after his death. The Parliament of Poland declared 2011, his 100th birth anniversary, the "Year of Miłosz." Streets are named after him in several cities. In 2013, a primary school in Vilnius was named after him.

His Impact on Culture

The poet Joseph Brodsky called Miłosz "one of the great poets of our time." Many writers have said Miłosz influenced them. Scholars have noted his impact on poets like Seamus Heaney and Robert Hass.

Miłosz's writings were secretly brought into Poland. They inspired the anti-communist Solidarity movement in the early 1980s. Lines from his poem "You Who Wronged" are carved on a monument in Gdańsk. This is where the Solidarity movement began.

Miłosz's book Postwar Polish Poetry also had a big effect on English-speaking poets. It made them think about poetry in new ways. It encouraged them to write about important historical and intellectual topics.

Miłosz's work is still studied today. His papers, including his writings and letters, are kept at Yale University.

What Miłosz Wrote About

Different Ways of Writing

Miłosz wrote in many different ways. He wrote poetry, novels, autobiography, scholarly works, and essays. His letters to other writers have also been published.

Early in his career, Miłosz was called a "catastrophist" poet. This meant he and other poets used unusual images and forms. They did this to react to a Europe filled with extreme ideas and war. Miłosz continued to experiment with different forms throughout his career. His poems range from very long ones, like A Treatise on Poetry, to very short ones. He used both free verse (no strict rules) and classic forms like the ode. Sometimes his poems rhymed, but often they did not. He often used different forms to show different meanings in his poems.

Main Ideas in His Work

Miłosz's work is known for being complex. But some common ideas appear throughout his writings.

He was known as a "poet of great inclusiveness." This means he tried to capture all the different parts of life. His poems often show "contradiction." One idea might be presented, and then immediately challenged. This use of many voices helped show the complexity of the modern world. It also helped him search for what is right and wrong.

Miłosz often explored what it means to be moral. He wanted his readers to see the different sides of their own experiences. This forces people to make conscious choices, which is part of being moral. For example, in The Captive Mind, he thought about how to help three Lithuanian women forced to live on a Russian farm. In his poems "Campo Dei Fiori" and "A Poor Christian Looks at the Ghetto," he wrote about feeling guilty for surviving when others suffered.

Miłosz's ideas about morality are always connected to history. He believed that people are always part of history. He had lived through Nazism and Stalinism. He was very concerned about the idea of "historical necessity." This idea was used in the 20th century to excuse terrible suffering. But Miłosz did not completely reject this idea. He thought that some things in history, like the rise and fall of civilizations, might have their own logic. But he also reminded readers not to forget the millions of people who suffered for these historical changes.

Miłosz also showed a great sense of wonder and faith in his writing. This was not always religious faith. It was a belief in the realness of the world around us. Sometimes, Miłosz was more openly religious. His writing often refers to Christian ideas. He saw the universe as having both good and evil forces. From this view, he could accept that the world has evil. Yet, he could still find hope and beauty in it. History might show that human efforts are pointless. But time also offers a glimpse of eternity. This viewpoint meant Miłosz tried to "suffer time" and "live in the hope of the redemption of the world."

Who Influenced Miłosz

Many writers and thinkers influenced Miłosz. Some of the most important ones include:

- Oscar Miłosz: His cousin, who sparked his interest in deep, philosophical ideas.

- Simone Weil: A French philosopher whose work Miłosz translated.

- Fyodor Dostoyevsky: A famous Russian novelist.

- William Blake: An English poet and artist.

- T. S. Eliot: An American-British poet.

See also

In Spanish: Czesław Miłosz para niños

In Spanish: Czesław Miłosz para niños

- List of Polish Poets

- Nobel Prize in Literature

- Polish literature

- List of Polish Nobel laureates

Images for kids

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |