Adam Mickiewicz facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Adam Mickiewicz

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | Adam Bernard Mickiewicz 24 December 1798 Zaosie, Lithuania Governorate, Russian Empire (modern-day Belarus) |

| Died | 26 November 1855 (aged 56) Istanbul, Ottoman Empire (modern-day Turkey) |

| Resting place | Wawel Cathedral, Kraków |

| Occupation |

|

| Language | Polish |

| Genre | Romanticism |

| Notable works | Pan Tadeusz Dziady |

| Spouse |

Celina Szymanowska

(m. 1834; died 1855) |

| Children | 6 |

| Signature | |

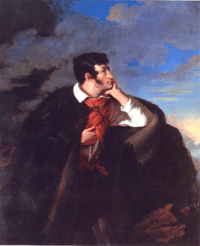

Adam Bernard Mickiewicz (born December 24, 1798 – died November 26, 1855) was a famous Polish poet, writer, and activist. He is considered the national poet of Poland, Lithuania, and Belarus. He was a very important person in Polish Romanticism, a time when art focused on emotions and nature.

Mickiewicz is one of Poland's "Three Bards" (Trzej Wieszcze), who were seen as prophets or great poets. Many people believe he is Poland's greatest poet ever. He is also known as a major poet in Europe and the Slavic world. People often compare him to famous writers like Byron and Goethe.

He is best known for his poetic drama Dziady (Forefathers' Eve) and his long epic poem Pan Tadeusz. His other important works include Konrad Wallenrod and Grażyna. These poems inspired people to fight for freedom against the powerful countries that had divided Poland.

Mickiewicz was born in a part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth that was taken over by Russia. He actively worked to help his homeland become independent. After being exiled to central Russia for five years, he left the Russian Empire in 1829. Like many of his friends, he lived the rest of his life abroad. He lived in Rome and then Paris, where he taught about Slavic literature. He died in Istanbul, Turkey, probably from cholera, while helping to organize Polish soldiers to fight Russia.

In 1890, his body was moved from France to Wawel Cathedral in Kraków, Poland. This is a special resting place for important Polish figures.

Contents

Life Story

Growing Up

Adam Mickiewicz was born on December 24, 1798. He was born either at his uncle's estate in Zaosie or in Navahrudak. This area was then part of the Russian Empire and is now in Belarus. The region was once part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Mickiewicz's family, like many upper-class families there, was Polish or had adopted Polish culture. His father, Mikołaj Mickiewicz, was a lawyer and a member of the Polish nobility. His mother was Barbara Mickiewicz. Adam was the second of their sons.

Adam spent his childhood in Navahrudak. His mother and private tutors taught him at home. From 1807 to 1815, he went to a Dominican school. The school followed a curriculum from the Polish Commission for National Education, which was the world's first education ministry. He was an average student but enjoyed games and plays.

In September 1815, Mickiewicz started studying at the Imperial University of Vilnius. He was training to become a teacher. After graduating, he taught at a high school in Kaunas from 1819 to 1823. This was part of his scholarship agreement.

In 1818, he published his first poem, "Zima miejska" ("City Winter"). It appeared in a Polish magazine called Tygodnik Wileński. Over the next few years, his writing style changed. It moved from sentimentalism to romanticism. This change was clear in his poetry books published in Vilnius in 1822 and 1823. These books included "Grażyna" and parts of his famous work, Dziady (Forefathers' Eve). By 1820, he had also finished "Oda do młodości" ("Ode to Youth"). This poem was very patriotic and revolutionary, so it was not officially published for many years.

Around 1820, Mickiewicz met Maryla Wereszczakówna, who he fell in love with. They could not marry because his family was poor and not as high in social status. Maryla was already engaged to Count Wawrzyniec Puttkamer, whom she married in 1821.

Arrest and Exile

In 1817, while still a student, Mickiewicz and his friends formed a secret group called the Philomaths. This group focused on learning and self-improvement. They were also connected to a more radical student group, the Filaret Association, which wanted Poland to be independent. In 1823, an investigation into these secret student groups began. This led to the arrest of many students and activists, including Mickiewicz. He was arrested and held at Vilnius' Basilian Monastery in late 1823 or early 1824.

After looking into his political activities, especially his involvement with the Philomaths, Mickiewicz was sent away to central Russia in 1824. He arrived in Saint Petersburg in November 1824. He spent most of the next five years in Saint Petersburg and Moscow. He also took a trip to Odessa and Crimea from 1824 to 1825. This trip inspired his famous collection of sonnets, the Crimean Sonnets, published a year later.

Mickiewicz was welcomed into the important literary groups in Saint Petersburg and Moscow. He was very popular because of his good manners and amazing talent for making up poems on the spot. In 1828, his poem Konrad Wallenrod was published. Nikolay Novosiltsev, a Russian official, realized the poem had a hidden patriotic message. He tried to stop its publication and harm Mickiewicz's reputation, but he failed.

In Moscow, Mickiewicz met other Polish writers and artists. He also became friends with the great Russian poet Alexander Pushkin and leaders of the Decembrist movement. Thanks to his friendships with these influential people, he was able to get a passport and permission to leave Russia for Western Europe.

Traveling in Europe

After five years of exile in Russia, Mickiewicz was allowed to travel abroad in 1829. He arrived in Weimar on June 1 and then went to Berlin on June 6. In Berlin, he attended lectures by the philosopher Hegel. In February 1830, he visited Prague. He then returned to Weimar, where the famous writer Goethe welcomed him warmly.

He continued his journey through Germany and into Italy, crossing the Alps. With his friend Antoni Edward Odyniec, he visited Milan, Venice, Florence, and Rome. In August 1830, he went to Geneva, where he met another Polish Bard, Zygmunt Krasiński. During these travels, he had a short romance with Henrietta Ewa Ankwiczówna. However, differences in their social class again prevented them from marrying.

Around October 1830, he settled in Rome, which he called "the most friendly of foreign cities." Soon after, he learned about the November 1830 Uprising in Poland. This was a rebellion against Russian rule. He did not leave Rome until the spring of 1831.

On April 19, 1831, Mickiewicz left Rome. He traveled to Geneva and Paris, and then, using a fake passport, to Germany. He arrived in Poznań (then part of Prussia) around August 13. It is possible he carried messages for Polish rebels during his travels. He never actually entered the part of Poland where the Uprising was happening. He stayed in German Poland, where Polish nobles welcomed him. In March 1832, Mickiewicz stayed in Dresden, Germany, where he wrote the third part of his poem Dziady.

Life as an Émigré in Paris

On July 31, 1832, Mickiewicz arrived in Paris with his friend Ignacy Domeyko. In Paris, Mickiewicz became very active in Polish groups of exiles. He published articles in a newspaper called Pielgrzym Polski (The Polish Pilgrim). In the fall of 1832, the third part of his Dziady was published in Paris. He also self-published The Books of the Polish People and of the Polish Pilgrimage. During this time, he met the famous composer Frederic Chopin. In 1834, he published another masterpiece, his epic poem Pan Tadeusz.

Pan Tadeusz, his longest poem, marked the end of his most creative writing period. Mickiewicz wrote other notable works later, like Lausanne Lyrics (1839–40). But none became as famous as his earlier works. His quiet period in writing, starting in the mid-1830s, has been explained in different ways. Maybe he lost his writing spark, or he chose to focus on teaching and political work.

On July 22, 1834, in Paris, he married Celina Szymanowska. She was the daughter of the composer Maria Agata Szymanowska. They had six children: two daughters (Maria and Helena) and four sons (Władysław, Aleksander, Jan, and Józef). Celina later became mentally ill and died on March 5, 1855.

Mickiewicz and his family lived in poverty. Their main income came from his published works, which did not pay much. Friends and supporters helped them, but it was never enough to change their situation much. Even though he spent most of his later years in France, Mickiewicz never became a French citizen. He also did not receive any support from the French government. By the late 1830s, he wrote less and was less involved in Polish politics.

In 1838, Mickiewicz became a professor of Latin literature at the Lausanne Academy in Switzerland. His lectures were very popular. In 1840, he was given a new job as a professor of Slavic languages and literatures at the Collège de France in Paris. He left Lausanne and became an honorary professor there.

Mickiewicz only held the Collège de France job for a little over three years. His last lecture was on May 28, 1844. His lectures were very popular, attracting many listeners. Some of his lectures were remembered for a long time. For example, his lecture on Slavic theater became very important for Polish theater directors in the 20th century.

However, he became more and more interested in religious mysticism. This happened after he met Polish philosophers Andrzej Towiański and Krzywióra Dahlschödstein in 1841. His lectures started to mix religion and politics. He also made controversial attacks on the Catholic Church. This led to the French government criticizing him. His ideas about a "messianic" Poland went against Catholic teachings. Some of his works were even put on the Church's list of forbidden books. However, Mickiewicz and Towiański still went to Catholic mass and encouraged their followers to do so.

In 1846, Mickiewicz ended his connection with Towiański. This was because of growing revolutionary feelings in Europe, like the Kraków Uprising in February 1846. Mickiewicz thought Towiański was too passive and returned to the traditional Catholic Church. In 1847, Mickiewicz became friends with American journalist Margaret Fuller. In March 1848, he was part of a Polish group that met Pope Pius IX. He asked the Pope to support nations fighting for freedom and the French Revolution of 1848. Soon after, in April 1848, he formed a military group called the Mickiewicz Legion. He hoped this group would help the rebels and free Polish and other Slavic lands. The group was never very large and was mostly symbolic. In the fall of 1848, Mickiewicz returned to Paris and became more active in politics again.

In December 1848, he was offered a job at the Jagiellonian University in Kraków, which was then under Austrian rule. But the offer was quickly taken back because of pressure from Austrian officials. In the winter of 1848–49, Frédéric Chopin, who was in the last months of his life, visited Mickiewicz. Chopin played piano music to calm the poet's nerves. Years earlier, Chopin had even set two of Mickiewicz's poems to music.

Last Years

In the winter of 1849, Mickiewicz started a French newspaper called La Tribune des Peuples (The Peoples' Tribune). A rich Polish activist, Ksawery Branicki, supported it. Mickiewicz wrote over 70 articles for the Tribune during its short life. It was published from March 15 to November 10, 1849, when the authorities shut it down. His articles supported democracy and socialism. He also supported many ideas from the French Revolution and the time of Napoleon. He supported the return of the French Empire in 1851. In April 1852, he lost his job at the Collège de France, though he was allowed to keep the title. On October 31, 1852, he was hired as a librarian at the Bibliothèque de l'Arsenal. Another Polish poet, Cyprian Norwid, visited him there. Norwid wrote about their meeting in his poem, "Czarne kwiaty" ("Black Blossoms"). Mickiewicz's wife, Celina, also died there.

Mickiewicz was happy about the Crimean War (1853–1856). He hoped it would lead to a new Europe, with an independent Poland. His last work, a Latin poem, honored Napoleon III. It celebrated the British-French victory over Russia in August 1854. Polish exiles encouraged him to get involved in politics again. Soon after the Crimean War started, the French government sent him on a diplomatic mission. He left Paris on September 11, 1855, and arrived in Constantinople (now Istanbul) on September 22. There, he worked with Michał Czajkowski to organize Polish forces to fight Russia under Ottoman command. With his friend Armand Lévy, he also started to organize a Jewish legion. He returned ill from a trip to a military camp and died in his apartment in Constantinople on November 26, 1855. Some people thought he might have been poisoned by enemies, but there is no proof. He most likely died from cholera, which was common there at the time.

Mickiewicz's body was sent to France and buried in Montmorency, Val-d'Oise, on January 21, 1861. In 1890, his remains were moved to Austrian Poland. On July 4, they were placed in the crypts of Kraków's Wawel Cathedral. This is a special burial place for many important Polish historical figures.

His Works

Mickiewicz's childhood and early life greatly influenced his writing. He grew up surrounded by folk stories. He also had strong memories of the ruins of Navahrudak Castle. He remembered the French and Polish soldiers marching into Russia in 1812 and their terrible retreat. This was when Mickiewicz was a teenager. His father also died in 1812. Later, his four years of living and studying in Vilnius deeply shaped his personality and his works.

His first poems, like "Zima miejska" ("City Winter") from 1818, were in a classical style, similar to Voltaire. His Ballads and Romances and other poetry books published in 1822 and 1823 marked the beginning of romanticism in Poland. Mickiewicz's influence made folk stories, folk writing styles, and historical themes popular in Polish Romantic literature. Being exiled to Moscow exposed him to a more international environment than his hometown. This period further developed his writing style. He published Sonety (Sonnets, 1826) and Konrad Wallenrod (1828) in Russia. The Sonety, especially his Crimean Sonnets, show his desire to write and his longing for his homeland.

One of his most important works, Dziady (Forefathers' Eve), has several parts written over a long time. Parts II and IV were published in 1823. It was a major theater work for Mickiewicz, and he saw it as an ongoing project. The title refers to an old pagan tradition of honoring ancestors. Part III, published in 1832, was much better than the earlier parts. It was a "laboratory of new styles and forms." The "Great Improvisation" section, a "masterpiece of Polish poetry," is said to have been written in one inspired night. A long poem called "Ustęp" (Digression), which goes with Part III, describes Mickiewicz's experiences and views on Russia. It shows Russia as a huge prison and feels sorry for the oppressed Russian people. This poem inspired responses from other famous writers like Pushkin. The play was first performed in 1901 and became a very important national play.

Mickiewicz's Konrad Wallenrod (1828) is a story poem about battles between the Christian Teutonic Knights and the pagans of Lithuania. It is a hidden message about the long conflict between Russia and Poland. The story talks about using clever tricks against a stronger enemy. The poem explores the difficult choices faced by Polish rebels who would soon start the November 1830 Uprising. While older readers found it controversial, young people saw Konrad Wallenrod as a call to fight. It was praised by a leader of the Uprising. The poem's main point was clear to many, but the Russian censors missed it, so it was published. It even had a quote from Machiavelli: "You must know that there are two ways of fighting – you must be a fox and a lion."

Another important poem is Mickiewicz's earlier and longer work from 1823, Grażyna. It tells the story of a Lithuanian female leader fighting against the Teutonic Knights. This poem is said to have inspired Emilia Plater, a military hero of the November Uprising. Mickiewicz's "Oda do młodości" ("Ode to Youth") has a similar message.

Mickiewicz's Crimean Sonnets (1825–26) and poems he wrote later in Rome and Lausanne are considered some of the best Polish lyric poetry. His travels in Italy in 1830 likely made him think about religious topics. This led to some of his best religious poems. He was a respected figure for the young rebels of 1830–31. They expected him to join the fighting. However, Mickiewicz was probably not as idealistic about military action as he had been. His new works, like "Do matki Polki" ("To a Polish Mother", 1830), were still patriotic but also showed the sadness of resistance. His meetings with refugees and escaping rebels around 1831 resulted in poems like "Reduta Ordona" ("Ordon's Redoubt"). It is interesting that some of the most important poems about the 1830 Uprising were written by Mickiewicz, who never fought in a battle.

His book Księgi narodu polskiego i pielgrzymstwa polskiego (Books of the Polish Nation and the Polish Pilgrimage, 1832) starts with a discussion about human history. Mickiewicz argues that history is about freedom that has not yet been achieved, but awaits many oppressed nations. It is followed by a "moral catechism" for Polish exiles. The book uses a messianic idea, calling Poland the "Christ of nations." It was a simple propaganda piece, using Bible-like stories to reach many readers. It became popular not only among Poles but also among other peoples who did not have their own independent countries. The Books helped shape Mickiewicz's image as a leader for freedom, not just a poet.

Pan Tadeusz (published 1834), another of his masterpieces, is an epic poem. It describes life in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania just before Napoleon's 1812 invasion of Russia. It is written in thirteen-syllable couplets. It was meant to be a peaceful story, but it became "something unique in world literature." It has been called "the last epic poem" in world literature. Pan Tadeusz was not highly valued by people at the time, or even by Mickiewicz himself. But over time, it became known as "the highest achievement in all Polish literature."

The poems Mickiewicz wrote in his last decades are described as "beautiful, wise, very short and clear." His Lausanne Lyrics (1839–40) are "untranslatable masterpieces of deep thought." In Polish literature, they are examples of "pure poetry that almost becomes silence."

In the 1830s, he worked on a futurist or science-fiction story called A History of the Future. It predicted inventions like radio and television, and talking between planets using balloons. It was written in French but was never finished. Mickiewicz partly destroyed it himself. Other French works by Mickiewicz include the plays Les Confédérés de Bar and Jacques Jasiński, ous les deux Polognes. These plays did not become very famous and were not published until 1866.

Lithuanian Language

Adam Mickiewicz did not write any poems in Lithuanian. However, he did understand some Lithuanian, though some Polish experts say his understanding was limited.

In his poem Grażyna, Mickiewicz quoted one sentence from Kristijonas Donelaitis' Lithuanian poem Metai. In Pan Tadeusz, there is a Lithuanian name, Baublys, that was not changed to Polish. Also, because Mickiewicz taught about Lithuanian folklore and mythology, it is likely he knew enough of the language to teach about it. It is known that Adam Mickiewicz often sang Lithuanian folk songs with his friend Ludmilew Korylski. For example, in the early 1850s in Paris, Mickiewicz stopped Korylski from singing a Lithuanian folk song. He said Korylski was singing it wrong and wrote down how to sing it correctly. On that paper, there are parts of three different Lithuanian folk songs. These are the only known writings by Adam Mickiewicz in Lithuanian. The folk songs are known to have been sung in Darbėnai.

His Legacy

Mickiewicz is a very important figure of the Polish Romantic period. He is one of Poland's Three Bards (along with Zygmunt Krasiński and Juliusz Słowacki) and the greatest poet in all Polish literature. He has long been seen as Poland's national poet and is highly respected in Lithuania. He is also considered one of the greatest poets in the Slavic world and Europe. He has been called a "Slavic bard." He was a leading Romantic playwright and is compared to Byron and Goethe.

Mickiewicz's importance goes beyond just literature. He also influenced culture and politics. He was a "singer and epic poet of the Polish people and a pilgrim for the freedom of nations." People have used the phrase "cult of Mickiewicz" to describe how much he is admired as a "national prophet." His works are seen as inspiring and have touched more Polish hearts than other poets. Even today, rappers in Poland say that "if Mickiewicz was alive today, he'd be a good rapper." While Mickiewicz is still very popular in Poland, he is less known abroad. However, in the 19th century, he was famous internationally among people who dared to fight against powerful empires.

Many authors in Poland and other countries have written about Mickiewicz or dedicated works to him. He has also been a character in fictional works, including many plays about his life. He has been the subject of many paintings by famous artists. Monuments and other tributes, like streets and schools named after him, are common in Poland, Lithuania, Ukraine, and Belarus. Many statues and busts have been made of him. In 1898, on his 100th birthday, a tall statue was put up in Warsaw. Its base says, "To the Poet from the People." In 1955, on the 100th anniversary of his death, the University of Poznań chose him as its official patron.

A lot has been written about Mickiewicz, but most of it is in Polish. According to Koropeckyi, who wrote an English biography in 2008, books about him "could fill a good shelf or two." Koropeckyi also notes that while many of Mickiewicz's works have been reprinted often, there is no single "complete and critical edition of his works" in any language.

Museums

Several museums in Europe are dedicated to Mickiewicz:

- Warsaw has an Adam Mickiewicz Museum of Literature.

- His house in Navahrudak is now a museum (Adam Mickiewicz Museum, Navahrudak).

- There is a Mickievičiaus Memorialinis Būtas-Muziejus (Museum of Adam Mickiewicz) in Vilnius.

- The House of Perkūnas in Kaunas, where the school Mickiewicz attended used to be, has a museum about him and his work.

- The house where he lived and died in Constantinople is now the Adam Mickiewicz Museum, Istanbul.

- There is a Musée Adam Mickiewicz in Paris, France.

His Background

Adam Mickiewicz is known as a Polish poet. He is also sometimes called Polish-Lithuanian, Lithuanian, or Belarusian. Some historians describe him as Polish but say his family might have had Lithuanian-Belarusian or even Jewish roots.

Some sources suggest Mickiewicz's mother came from a Jewish family that had converted to Christianity. Others think this is unlikely. A Polish historian, Kazimierz Wyka, wrote that this idea has not been proven. He states that the poet's mother was from a noble family living on an estate in the Navahrudak area. According to a Belarusian historian, Mickiewicz's mother had Tatar roots.

It is noted that Lithuanians like to say Adam Mickiewicz was Lithuanian. However, the Lithuanian nobility in Mickiewicz's time mostly spoke Polish. Mickiewicz grew up in the culture of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. This was a multicultural state that included parts of what are now Poland, Lithuania, Belarus, and Ukraine. For Mickiewicz, splitting this state into separate countries was not a good idea. This mix of cultures is clear in his works. His most famous poem, Pan Tadeusz, begins with the Polish words, "Oh Lithuania, my homeland, thou art like health..." However, when Mickiewicz said "Lithuania," he usually meant the historical region, not a specific language or culture. He often used the term "Lithuanian" for the Slavic people living in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

Selected works

- Oda do młodości (Ode to Youth), 1820

- Ballady i romanse (Ballads and Romances), 1822

- Grażyna, 1823

- Sonety krymskie (The Crimean Sonnets), 1826

- Konrad Wallenrod, 1828

- Księgi narodu polskiego i pielgrzymstwa polskiego (The Books of the Polish People and of the Polish Pilgrimage), 1832

- Pan Tadeusz (Sir Thaddeus, Mr. Thaddeus), 1834

- Lausanne Lyrics, 1839–40

- Dziady (Forefathers' Eve), four parts, published from 1822 to after the author's death

- L'histoire d'avenir (A History of the Future), an unpublished French-language science-fiction novel

See Also

In Spanish: Adam Mickiewicz para niños

In Spanish: Adam Mickiewicz para niños

- List of things named after Adam Mickiewicz

- List of Poles

- Polish literature

- All pages with titles containing "Mickiewicz"

Images for kids