November Uprising facts for kids

Quick facts for kids November Uprising |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Revolutions of 1830 and Russo-Polish Wars |

|||||||

Taking of the Warsaw Arsenal. Painting by Marcin Zaleski. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Congress Poland

|

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Strength | |||||||

150,000 |

180,000–200,000 |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Polish claim: 40,000 killed and wounded | Polish claim: about 22,000–23,000 killed and wounded |

||||||

The November Uprising (1830–31) was a big rebellion by Poles against the Russian Empire. It is also known as the Polish–Russian War 1830–31 or the Cadet Revolution. The uprising started on November 29, 1830, in Warsaw. Young Polish officers from a military school led by Lieutenant Piotr Wysocki began the fight. People in Lithuania, Belarus, and Right-bank Ukraine soon joined them. Even though the Poles had some early wins, a much larger Russian army eventually defeated the uprising.

After the rebellion, the Russian Emperor Nicholas I made new rules in 1832. These rules meant that Russian-controlled Poland lost its freedom and became a direct part of the Russian Empire. Warsaw became a military base, and its university was closed.

Contents

Why the Uprising Started

Poland's History Before the Uprising

For a long time, Poland was a powerful country. But by 1795, it was divided up by three big empires: Austria, Prussia, and Russia. This meant Poland no longer existed as an independent country.

Later, during the Napoleonic Wars, a small Polish state called the Duchy of Warsaw was created. But after Napoleon's defeat, the Congress of Vienna in 1815 divided Poland again. Russia took control of a part called Congress Poland.

Losing Freedom in Congress Poland

At first, Congress Poland had some freedom. It had its own constitution, parliament, government, courts, army, and money. The Russian Tsar was also the King of Poland, but the Poles could elect their own parliament.

However, over time, Russia started taking away these freedoms. The Tsar, Alexander I, never officially became King of Poland. Instead, he put his brother, Grand Duke Constantine Pavlovich, in charge. Constantine often ignored the Polish constitution.

In 1819, freedom of the press was stopped, and censorship began. Russian secret police started watching and bothering Polish secret groups. In 1821, the Tsar even banned Freemasonry. By 1825, meetings of the Polish parliament had to be held in secret. In 1829, the new Tsar, Nicholas I, officially crowned himself King of Poland in Warsaw.

Grand Duke Constantine was not liked by the Poles. He removed Polish organizations and replaced Poles with Russians in important jobs. Even though he was married to a Polish woman, he was seen as an enemy. His way of leading the Polish Army also caused many problems with the officers. This led to secret plans for a rebellion across the country, especially within the army.

The Uprising Begins

The fighting started on November 29, 1830. A group of young officers, led by Piotr Wysocki, attacked the Belweder Palace. This was where Grand Duke Constantine lived. The main reason for the uprising was a Russian plan to use the Polish Army to stop revolutions in France and Belgium. This plan went against the Polish constitution.

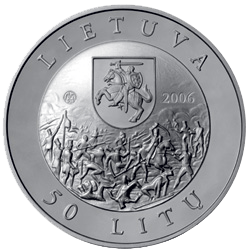

The rebels got into the Belweder Palace, but Grand Duke Constantine managed to escape. The rebels then went to the main city arsenal and captured it. The next day, Polish citizens joined the fight. They forced the Russian troops to leave Warsaw. This event is sometimes called the Warsaw Uprising or the November Night (Polish: Noc listopadowa).

Fighting for Freedom

The Polish government was surprised by how fast things happened. They quickly formed a new council to take charge. They removed unpopular ministers and brought in new leaders like Prince Adam Jerzy Czartoryski and General Józef Chłopicki. At first, they tried to talk with Grand Duke Constantine to find a peaceful solution.

However, some radical leaders, like Maurycy Mochnacki, wanted a full national uprising. They did not trust the new government. Mochnacki organized the Patriotic Club. On December 3, he spoke at a big public meeting in Warsaw. He demanded a revolutionary government and an attack on Constantine's forces. The Polish army, with most of its generals, joined the uprising.

A new "provisional government" was formed. On December 5, 1830, General Chłopicki was named "dictator of the uprising." Chłopicki thought the uprising was a bad idea. He believed Russia was too strong. He hoped to end the conflict peacefully and save the constitution.

Chłopicki sent Prince Franciszek Ksawery Drucki-Lubecki to Saint Petersburg to talk with the Tsar. Chłopicki did not make the Polish army stronger. He also refused to attack Russian forces in Lithuania. But the radicals in Warsaw wanted war and complete freedom for Poland. On December 13, the Polish parliament declared a "National Uprising" against Russia.

On January 7, 1831, Prince Drucki-Lubecki returned with bad news. The Tsar demanded that Poland surrender completely. Chłopicki resigned the next day.

Power then went to the radical "Patriotic Society" led by Joachim Lelewel. On January 25, 1831, the parliament officially removed Nicholas I as King of Poland. This was like a declaration of war on Russia. They said, "the Polish nation is an independent people."

On January 29, a new national government was set up. Michał Gedeon Radziwiłł became the new leader, and Chłopicki agreed to lead the army again.

The Polish-Russian War

The war began when a large Russian army of 115,000 soldiers, led by Field Marshal Hans Karl von Diebitsch, crossed into Poland on February 4, 1831.

The first big battle was on February 14, 1831, near the village of Stoczek. Polish cavalry, led by Brigadier Józef Dwernicki, defeated a Russian division. This victory was important for Polish morale, but it did not stop the Russians from moving towards Warsaw. Other battles, like those at Dobre, Wawer, and Białołęka, did not have clear winners.

The Polish forces gathered near the Vistula River to protect Warsaw. On February 25, about 40,000 Polish soldiers met 60,000 Russian soldiers east of Warsaw at the Battle of Olszynka Grochowska. Both armies fought hard for almost two days. Both sides lost many soldiers. Over 7,000 Poles died, and even more Russians were killed. Diebitsch had to retreat, and Warsaw was saved for a while.

Chłopicki was wounded in this battle. General Jan Skrzynecki took his place. Skrzynecki also believed that fighting Russia was hopeless. He tried to end the war through talks and hoped other countries would help.

Many people across Europe supported the Poles. Meetings were held in Paris, and money was collected in the United States. However, the governments of France and Britain did not want to get involved. They wanted to stay friends with Russia. Austria and Prussia also stayed neutral and did not allow supplies to reach Poland.

The war became very difficult for the Poles. They fought bravely. There were attempts to start uprisings in other areas like Lithuania. Young Countess Emilia Plater and other women fought in the Lithuanian uprising. But these smaller fights were not enough. New Russian forces arrived in Poland. Constant fighting and bloody battles, like the one at Ostroleka, where 8,000 Poles died, weakened the Polish army. Mistakes by commanders and constant changes in leadership also caused despair.

Some people wanted the government to make changes, like giving peasants more rights to their land. But the parliament was slow to act. They were afraid that other European countries would see the war as a social revolution. Because of this, the initial excitement among the peasants faded.

Meanwhile, the Russian army, now led by General Paskevich (after Diebitsch died), began to surround Warsaw. Skrzynecki failed to stop the Russian armies from joining up. The people demanded his removal, and General Dembinski took temporary command. There were riots, and the government became very disorganized. Count Jan Krukowiecki became the head of the Ruling Council. He believed the war could not be won.

On September 6, Warsaw's suburb of Wola fell to Paskevich's forces. The next day, the Russians attacked the city's main defenses. During the night of September 7, Krukowiecki surrendered, even though parts of the city were still fighting. He was immediately removed from power, and Bonawentura Niemojowski took his place. The army and government moved to the Modlin fortress.

Then came news that a Polish army group under Ramorino, which could not join the main army, had surrendered after crossing into Austria. It was clear the war could not continue.

On October 5, 1831, the rest of the Polish army, over 20,000 men, crossed into Prussia and surrendered their weapons. They chose this rather than surrendering to Russia.

Many Polish soldiers, following the example of Dąbrowski from an earlier generation, tried to form new groups in Prussia and Galicia to go to France. But the Prussian government stopped their plans. The Polish immigrants traveled through German areas and were often welcomed by the local people. Even some German rulers showed sympathy. Only after strong demands from Russia were the Polish support groups in Germany closed.

What Happened Next

After the November Uprising ended, Polish women wore black ribbons and jewelry. This was a way to show sadness for their lost homeland. You can see this in the movie Pan Tadeusz (1999), which is based on a famous Polish story.

The Scottish poet Thomas Campbell was very sad when he heard that Warsaw had been captured by the Russians. He wrote that "Poland preys on my heart night and day." He even helped start the "Association of the Friends of Poland" in London. The November Uprising also had supporters in the United States. The famous writer Edgar Allan Poe felt sympathy for the Polish cause.

Even though many Poles in the rebellion were Catholic, the Church condemned the uprising. Pope Gregory XVI wrote a letter in 1832 about civil disobedience. He said that the rebellion was caused by "fabricators of deceit and lies" who rebelled against "legitimate authority."

See also

- Great Emigration

- Warszawianka 1831 roku

- Revolutionary etude

- Hôtel Lambert

- Polish National Government (November Uprising)

- Sources in Polish

- Stanislas Hernisz

General:

- List of wars involving Poland