Pierre Boulez facts for kids

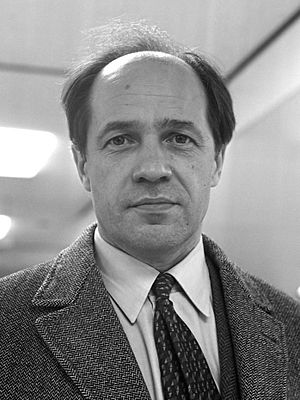

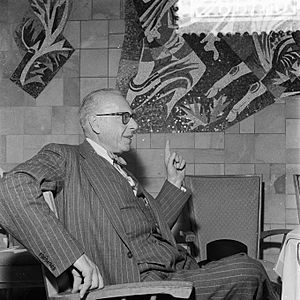

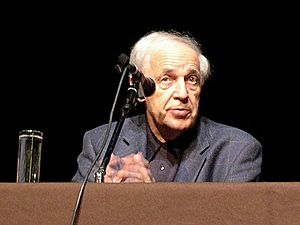

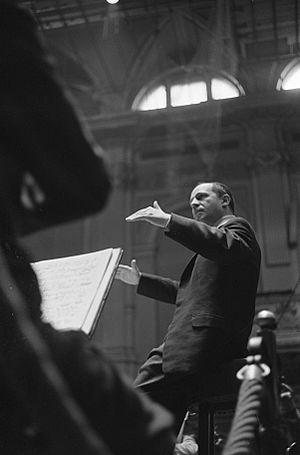

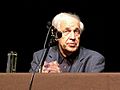

Pierre Louis Joseph Boulez (born March 26, 1925 – died January 5, 2016) was a famous French composer, conductor, and writer. He also started several important music organizations. He was one of the most influential people in classical music after World War II.

Boulez was born in Montbrison, France. He studied music at the Paris Conservatoire with Olivier Messiaen and also learned from other teachers. He started his career in the late 1940s as a music director for a theater company in Paris. He was a leader in new, experimental music. He helped develop musical styles like integral serialism (where many parts of music are organized in a series) and controlled chance music (where some parts are left to chance, but in a planned way). He also explored using electronics to change instrumental music live.

Boulez often changed his older compositions, so he didn't have a huge number of works. But many of his pieces, like Le Marteau sans maître and Répons, are considered very important in 20th-century music. He was very dedicated to modern music, and some people thought his strong opinions made him seem a bit strict.

Besides composing, Boulez was also one of the best conductors of his time. For over sixty years, he led many famous orchestras, including the New York Philharmonic and the BBC Symphony Orchestra. He was known for performing music from the first half of the 20th century, by composers like Claude Debussy, Igor Stravinsky, and Béla Bartók. He also conducted works by composers of his own time. He conducted famous operas, including Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen for its 100th anniversary at the Bayreuth Festival. He made many recordings throughout his career.

Boulez also founded several key music institutions. These include the Domaine musical, IRCAM (a research center for music and sound), the Ensemble intercontemporain (a group for new music), and the Cité de la Musique in Paris. He also started the Lucerne Festival Academy in Switzerland.

Contents

- A Look at Pierre Boulez's Life

- Early Years and School (1925–1943)

- Music Studies in Paris (1943–1946)

- Starting His Career in Paris (1946–1953)

- Starting the Domaine musical (1954–1959)

- Conducting Around the World (1959–1971)

- Leading Orchestras in London and New York (1971–1977)

- Leading IRCAM (1977–1992)

- Back to Conducting (1992–2006)

- Final Years (2006–2016)

- Boulez's Compositions

- Boulez's Personality

- Boulez as a Conductor

- Boulez and Opera

- Boulez's Recordings

- Boulez as a Performer

- Writing and Teaching

- Boulez's Impact

- Awards and Honors

- Images for kids

- See also

A Look at Pierre Boulez's Life

Early Years and School (1925–1943)

Pierre Boulez was born on March 26, 1925, in Montbrison, a small town in France. His father, Léon, was an engineer and a strong person, while his mother, Marcelle, was cheerful and friendly. Pierre was the third of four children. The family did well and moved to a comfortable house where Pierre grew up.

From age seven, Boulez went to a Catholic school. He took piano lessons, played music with friends, and sang in the school choir. When he was older, his father wanted him to become an engineer. So, Boulez studied advanced math in Lyon.

In Lyon, Boulez heard an orchestra for the first time and saw his first operas. He also met a famous singer, Ninon Vallin, who was impressed by his piano playing. She convinced his father to let him try to get into the Lyon Conservatoire, a music school. He was not accepted, but he was determined to become a musician. The next year, with his sister's help, he studied piano and harmony privately. In 1943, he moved to Paris to try to join the Conservatoire de Paris. His father even went with him and helped him settle in.

Music Studies in Paris (1943–1946)

In October 1943, Boulez tried out for the advanced piano class at the Conservatoire but didn't get in. However, in January 1944, he was accepted into a harmony class with Georges Dandelot. He learned so quickly that Dandelot called him "the best of the class."

Around this time, he met Andrée Vaurabourg, a composer's wife. He studied counterpoint (a way of combining melodies) with her privately for two years. She thought he was an amazing student. In June 1944, he also started studying with Olivier Messiaen, a very important composer. Boulez joined Messiaen's advanced harmony class at the Conservatoire in 1945.

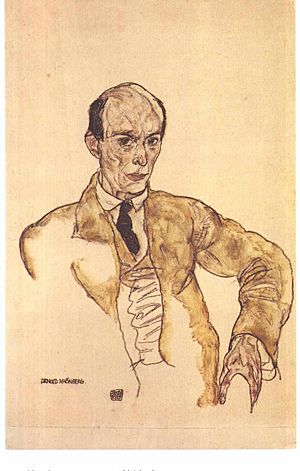

Boulez moved to small attic rooms in Paris, where he lived for the next thirteen years. In 1945, he heard a performance of Schoenberg's Wind Quintet, which used a strict "twelve-tone technique." This was a big discovery for him. He then took private lessons with René Leibowitz, who taught him more about this technique and the music of Anton Webern. However, Boulez later felt Leibowitz's teaching was too strict and they stopped working together in 1946.

In June 1945, Boulez was one of four students at the Conservatoire to win a top prize. Examiners called him "the most gifted—a composer." He also spent time learning about Balinese music, Japanese music, and African drumming in Paris museums. He said this music gave him "a different feeling of time."

Starting His Career in Paris (1946–1953)

In February 1946, Boulez's music was performed publicly for the first time. He earned money by teaching math and playing the ondes Martenot, an early electronic instrument, for radio shows and in theaters. In October 1946, the famous actor and director Jean-Louis Barrault hired him to play the ondes for a play. Boulez soon became the music director for Barrault's theater company, a job he kept for nine years. This allowed him to work with professional musicians and still have time to compose.

Working with the company also let him travel. They toured Belgium, Switzerland, Edinburgh, London, and even North and South America. Much of the music he wrote for the company was lost during student protests in 1968.

From 1947 to 1950, Boulez composed a lot. He wrote his first two piano sonatas and early versions of two cantatas (vocal pieces) based on poems by René Char. In October 1951, a piece for eighteen instruments called Polyphonie X caused a stir at its first performance, with some audience members booing.

Around this time, Boulez met two other important composers: John Cage and Karlheinz Stockhausen. He became good friends with Cage in 1949, and they wrote many letters to each other about the future of music. In 1952, Stockhausen came to Paris to study, and he and Boulez quickly became close friends, talking about music all the time.

In late 1951, a tour took Boulez to New York, where he met Igor Stravinsky and Edgard Varèse. He stayed at John Cage's apartment, but their friendship began to fade because Boulez didn't like Cage's increasing use of chance in his music.

In July 1952, Boulez attended the International Summer Course for New Music in Darmstadt, Germany. There, he met other important composers like Luciano Berio and Luigi Nono. Boulez quickly became a leader in the modern art movement after the war. People found his confidence reassuring during a time of confusion.

Starting the Domaine musical (1954–1959)

In 1954, with help from Barrault and Renaud, Boulez started a concert series called the Domaine musical in Paris. These concerts focused on three types of music: older classics not well known in Paris, new works by young composers, and forgotten old masters. Boulez was a great organizer, and the concerts were an instant hit. They attracted artists, writers, and even fashionable society.

Important moments for the Domaine musical included a festival for composer Webern in 1955 and the first European performance of Stravinsky's Agon in 1957. Boulez remained the director until 1967.

On June 18, 1955, Boulez's most famous work, Le Marteau sans maître (The Hammer without a Master), was first performed. This piece for a singer and instruments, based on poems by René Char, was an immediate international success. Many people felt it was a truly new and important work. When Boulez conducted it in Los Angeles in 1957, Stravinsky called it "one of the few significant works of the post-war period."

In January 1958, Boulez's Improvisations sur Mallarmé were first performed. These pieces grew into a larger, five-movement work called Pli selon pli, which was first heard in 1962. Around this time, Boulez's friendship with Stockhausen became strained, as Boulez felt Stockhausen was taking his place as a leader in new music.

Conducting Around the World (1959–1971)

In 1959, Boulez moved to Baden-Baden, Germany. He worked with the South-West German Radio orchestra as a composer and conductor. He also had access to an electronic music studio. He bought a large house there, which became his main home.

During this time, he started conducting more and more. His first time leading an orchestra was in 1956 in Venezuela. In 1959, he filled in for a sick conductor at two major festivals, which led to him conducting famous orchestras like the Amsterdam Concertgebouw and the Berlin Philharmonic. In 1963, he conducted the 50th anniversary performance of Stravinsky's The Rite of Spring in Paris, where it had caused a riot when first performed.

That same year, he conducted his first opera, Berg's Wozzeck, in Paris. He had many rehearsals, and the musicians loved working with him. He conducted Wozzeck again in 1966.

He was also invited to conduct Richard Wagner's Parsifal at the Bayreuth Festival, a very important event for Wagner's music. He conducted it several times. He also led performances of Wagner's Tristan und Isolde in Japan, but he was not happy with the lack of rehearsal. In contrast, his conducting of Debussy's Pelléas et Mélisande in London in 1969 was highly praised.

In 1965, the Edinburgh International Festival showed many of Boulez's works as both a composer and conductor. In 1966, he suggested changes to French music to the culture minister, but his ideas were rejected. Boulez was very angry and announced he would "go on strike" from official French music.

In March 1965, he made his US debut with the Cleveland Orchestra. He became their main guest conductor in 1969 and music advisor in 1970. He also made guest appearances in Boston, Chicago, and Los Angeles.

Besides Pli selon pli, his main new work in the early 1960s was the final version of his Structures for two pianos. Later in the decade, he started composing more new pieces, like Éclat (1965), a short, bright piece for a small group, which later grew into a longer work.

Leading Orchestras in London and New York (1971–1977)

Boulez first conducted the BBC Symphony Orchestra in 1964. His performances with them over the next five years included his debuts at the Proms (a famous British music festival) and Carnegie Hall in New York. In January 1969, he was named their chief conductor.

Two months later, Boulez conducted the New York Philharmonic for the first time. The orchestra and management were so impressed that they offered him the chief conductorship after Leonard Bernstein. Although his friends worried it would take away from his composing, Boulez accepted the chance to "reform the music-making of both these world cities."

His time in New York (1971–1977) was not entirely smooth. His programming was limited by the need to please regular audiences. He introduced more important works from the early 20th century. While the musicians admired his skill, some found him less emotional than Bernstein. However, it was widely agreed that he improved the orchestra's playing.

His time with the BBC Symphony Orchestra was happier. With the BBC's support, he could be more adventurous with his music choices. He focused intensely on 20th-century music. He conducted works by younger British composers. His relationships with the musicians were generally excellent. He was chief conductor from 1971 to 1975 and continued as chief guest conductor until 1977. He returned to the orchestra often until 2008.

In both cities, Boulez looked for places where new music could be performed more casually. In New York, he started "Rug Concerts" where the audience sat on the floor. In London, he gave concerts at the Roundhouse, a former railway building. His goal was to make everyone feel like they were "taking part in an act of exploration."

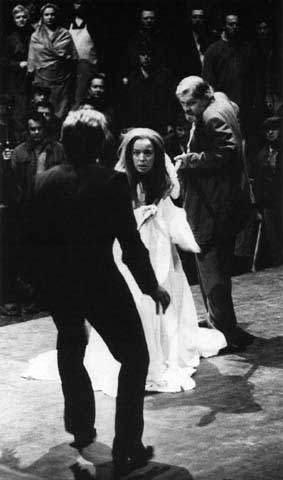

In 1972, Wolfgang Wagner invited Boulez to conduct the 1976 centenary production of Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen at Bayreuth. The director was Patrice Chéreau. This production was shown on TV around the world.

During this period, he composed a few new works, with Rituel in memoriam Bruno Maderna (1975) being one of the most important.

Leading IRCAM (1977–1992)

In 1970, French President Georges Pompidou asked Boulez to come back to France. He wanted Boulez to create an institute for musical research and creation in Paris. This institute, called the Institut de recherche et coordination acoustique/musique (IRCAM), opened in 1977.

Boulez wanted IRCAM to be a place where artists and scientists from all fields could meet, like the famous Bauhaus school. IRCAM's goals included studying acoustics, designing instruments, and using computers in music. The main building was built underground to keep it quiet. Some people criticized IRCAM for getting too much government money, and Boulez for having too much power. At the same time, he founded the Ensemble Intercontemporain, a group of talented musicians who played 20th-century music and new works.

In 1979, Boulez conducted the first performance of the full three-act version of Alban Berg's opera Lulu in Paris. After this, he conducted less often to focus on IRCAM. Most of his performances during this time were with his own Ensemble intercontemporain, including tours to the US, Australia, and the Soviet Union.

He composed much more during this period. He created pieces that used IRCAM's technology to change sounds electronically in real time. One of these was Répons (1981–1984), a 40-minute work for soloists, ensemble, and electronics. He also greatly reworked older pieces, like his Notations I-IV for orchestra.

In 1980, some of the original directors of IRCAM's departments resigned. Boulez called these changes "very healthy," but it showed there were problems with his leadership.

Special events celebrating his music were held in Paris (1981), Baden-Baden (1985), and London (1989). From 1976 to 1995, he held a special teaching position at the Collège de France. In 1988, he made a series of six TV shows about modern music. He also bought an apartment in Paris.

Back to Conducting (1992–2006)

In 1992, Boulez stepped down as director of IRCAM. He then became a composer-in-residence at the Salzburg Festival.

The year before, he started annual visits with the Cleveland Orchestra and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. In 1995, he was named principal guest conductor in Chicago, a position he held until 2005. His 70th birthday in 1995 was celebrated with a six-month tour with the London Symphony Orchestra, visiting Paris, Vienna, New York, and Tokyo. In 2001, he conducted a major series of Bartók's works with the Orchestre de Paris.

This period also saw him return to conducting opera. He worked with director Peter Stein on Debussy's Pelléas et Mélisande (1992) and Schoenberg's Moses und Aron (1995). In 2004 and 2005, he returned to Bayreuth to conduct a new production of Parsifal.

His two most important compositions from this time are ...explosante-fixe... (1993), which used IRCAM's electronic tools, and sur Incises (1998), for which he won a major award in 2001.

He continued to help organize music institutions. He co-founded the Cité de la Musique, which opened in Paris in 1995. This complex included a concert hall, museum, and media center, and became home to the Ensemble Intercontemporain. In 2004, he co-founded the Lucerne Festival Academy in Switzerland, a school for young musicians focusing on 20th and 21st-century music. For ten years, he spent summers working with young composers and conducting the Academy's orchestra.

Final Years (2006–2016)

Boulez's last major work was Dérive 2 (2006), a 45-minute piece for eleven instruments. He left several other compositions unfinished, including more of his orchestral Notations.

He continued to conduct for the next six years. In 2007, he worked again with director Chéreau on an opera. In April 2007, Boulez and Daniel Barenboim performed all of Gustav Mahler's symphonies in Berlin and later in New York. In late 2007, the Orchestre de Paris presented a look back at Boulez's music. In 2008, the Louvre museum had an exhibition about his work.

His conducting appearances became less frequent after an eye operation in 2010 left him with poor eyesight. He also had a shoulder injury. In late 2011, though quite frail, he led a tour of his own Pli selon pli in six European cities. His last time conducting was in Salzburg on January 28, 2012. After that, he canceled all his conducting jobs.

Later in 2012, he worked on the final changes to his only string quartet, Livre pour quatuor, which he started in 1948. In 2013, he oversaw the release of a 13-CD set of all his authorized compositions. He remained director of the Lucerne Festival Academy until 2014. His health kept him from attending the many celebrations for his 90th birthday in 2015.

Pierre Boulez died on January 5, 2016, at his home in Baden-Baden, Germany. He was buried there on January 13. A memorial service was held in Paris the next day, where many important figures spoke about his life and work.

Boulez's Compositions

Early Student Works

Boulez's earliest surviving pieces are from his school days (1942–43). These were mostly songs. They were described as "modest, delicate" and used common French music styles of the time.

As a student, Boulez composed pieces influenced by his teachers. His first piece using serial music was Thème et variations for piano (1945).

Douze notations and Ongoing Works

Boulez finished Douze notations (Twelve Notations) in December 1945. These are twelve short piano pieces, each twelve bars long. Later, he used two of them in another work. Then, in the 1970s, he began to transform these Notations into much larger works for orchestra. This project kept him busy until the end of his life.

This shows Boulez's habit of revisiting and changing his earlier works. He believed that his ideas should be explored in every possible way. He often made new versions of his pieces, with each version being a different stage of the music.

First Published Works

The Sonatine for flute and piano (1946–1949) was the first work Boulez allowed to be published. It's a very energetic serial work. One writer noted its "sharp, brittle violence mixed with extreme sensitivity." His Piano Sonata No. 1 (1946–49) is known for its many different ways of playing notes and fast changes in speed, creating a feeling of "instrumental excitement."

He then wrote two cantatas based on poems by René Char: Le Visage nuptial and Le Soleil des eaux. The latter went through several versions before its final form in 1965.

The Second Piano Sonata (1947–48) is a half-hour piece that requires amazing skill from the pianist. It follows the basic structure of a classical sonata but changes the traditional model. When Boulez played it for composer Aaron Copland, Copland asked, "But must we start a revolution all over again?" Boulez replied, "Yes, mercilessly."

Total Serialism

This "revolution" became very intense between 1950 and 1952. Boulez developed a technique called total serialism. In this, not only the notes but also other musical elements—like how long notes last, how loud they are, their sound quality, and how they are played—were organized using strict serial rules.

Boulez applied this technique very strictly. He organized each element into sets of twelve, making sure no element was repeated until all twelve had been used. This created a constant flow of changing musical information. Boulez said this was his generation's way of creating a "clean slate" after the war.

His works in this style include Polyphonie X (1950–51; later withdrawn) and Structures, Book I for two pianos (1951–52). Boulez later described Structures, Book I as a piece where "the responsibility of the composer is practically absent." He said it was an "absolutely necessary" experiment, even if he wasn't eager to listen to it himself.

Le Marteau sans maître and Pli selon pli

Structures, Book I was a turning point for Boulez. He realized that total serialism was too rigid. So, he made his music more flexible and expressive. The most important result of this new freedom was Le Marteau sans maître (The Hammer without a Master, 1953–1955). This piece is considered a "keystone of 20th-century music." It uses three short poems by René Char. Four movements are vocal settings of the poems, and five are instrumental commentaries. The music has sudden tempo changes, flowing melodies, and unique instrument sounds. Boulez said his choice of instruments (like alto flute, xylorimba, vibraphone, guitar, and viola) was influenced by non-European cultures.

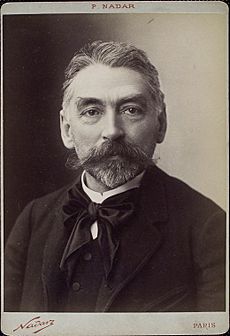

For his next major work, Pli selon pli (Fold by Fold, 1957–1989), Boulez used the complex poetry of Stéphane Mallarmé. At seventy minutes, it is his longest composition. It has three "Improvisations" on individual poems, surrounded by two orchestral movements. Boulez's goal was to make the poems become the music on a deeper, structural level. The piece is for soprano voice and a large orchestra, often used in smaller groups. Boulez described its sound as "extraordinarily 'vitrified'." The work changed over time, reaching its final form in 1989.

Controlled Chance in Music

From the 1950s, Boulez experimented with what he called "controlled chance." This is different from John Cage's use of chance. In Cage's music, performers might create unexpected sounds. But in Boulez's music, performers choose from possibilities that the composer has already written down. When this applies to the order of sections, it's called "mobile form."

Boulez used this technique in several works. In his Third Piano Sonata (1955–1957), the pianist can choose different paths through the score. In Éclat (1965), the conductor decides the order in which each player joins the group. In later works, like Cummings ist der Dichter (1970), the conductor has choices about the order of events, but individual players do not.

Figures—Doubles—Prismes (1957–1968) is a fixed work with no chance elements. It's a large set of variations where the parts blend into each other. It's also known for the unusual way the orchestra is set up, with different instrument families spread across the stage.

Middle-Period Works

From the mid-1970s, Boulez's music changed. It became clearer and more direct. Boulez himself said that the "outside" of his recent work was simpler, even if the "inside" was still complex. These works are among his most often performed.

Rituel in memoriam Bruno Maderna (1974–75) marks the start of this change. Boulez wrote this 25-minute piece to honor his friend, the composer and conductor Bruno Maderna, who died young. The piece is divided into fifteen sections, and the orchestra into eight groups. Some sections are conducted, while in others, a percussionist sets the pace. One writer called the work's feeling "awesome grandeur."

Notations I–IV (1980) are the first four transformations of his 1945 piano miniatures into pieces for a very large orchestra. A critic wrote that the original ideas were "broken into a thousand linked, lapped, sparkling fragments," with the finale being a "terse modern Rite which sets the pulses racing."

Dérive 1 (1984) is a short piece for five instruments, with the piano leading. The music is based on six chords, which are shuffled and decorated, spiraling outwards before returning to the start.

Works with Electronics

Boulez was not interested in listening to pre-recorded electronic music in a concert hall. He wanted to instantly change instrumental sounds live. This technology became available when IRCAM was founded in the 1970s. Before that, he had made some electronic pieces, but he was not happy with them and withdrew them.

The first piece finished at IRCAM was Répons (1980–1984). In this 40-minute work, an instrumental group is in the middle of the hall, while six soloists (two pianos, harp, cimbalom, vibraphone, and glockenspiel/xylophone) surround the audience. Their music is electronically transformed and projected through the space. One critic described how a "new sound world enters" when the soloists begin, and how natural and electronic sounds blend together.

Dialogue de l'ombre double (Dialogue of the Double Shadow, 1982–1985) for clarinet and electronics was a gift for composer Luciano Berio. It's a dialogue between a live clarinet and its "double," which is pre-recorded by the same musician and played through speakers around the hall.

In the early 1970s, Boulez worked on a piece called …explosante-fixe… for eight solo instruments with electronic changes. But the technology was still new, and he eventually withdrew it. He reused some of its ideas in a later piece with the same name. This final version (1991–1993) uses a special MIDI-flute and two other flutes with an ensemble and live electronics. The computer could follow the score and react to the players. The main flute's sound is imitated and echoed by the other flutes and the larger group.

Anthèmes II for violin and electronics (1997) grew from an earlier solo violin piece. The electronic system captures the violin's playing, transforms it in real time, and sends it around the space, creating a "hyper-violin." Even though this creates effects no violinist could do alone, Boulez kept the electronic sounds similar to the violin so its source is always clear.

Later Works

In his later works, Boulez stopped using electronics. However, in sur Incises (1996–1998), he used three pianos, three harps, and three percussionists spread across the stage. This allowed him to create echoes and special sound effects similar to what he used to do with electronics. This piece grew from a short piano piece. In 2013, he called sur Incises his most important work because it was "the freest."

Notation VII (1999) is the longest of his orchestral Notations. What was quick in 1945 became slow and flowing. What was simple became wonderfully detailed and rich.

Dérive 2 started as a five-minute piece in 1988. By 2006, it was a 45-minute work for eleven instruments and Boulez's last major composition. Boulez wanted to explore different rhythms, tempo changes, and layers of different speeds. He called it "a sort of narrative mosaic."

Unfinished Projects

Boulez left some works unfinished. For example, there are three unpublished movements of his Third Piano Sonata and more parts of Éclat/Multiples that would almost double its length if performed.

In his later years, Boulez was working on two more orchestral Notations (V and VI), but they were postponed. He was also developing Anthèmes 2 into a large work for violin and orchestra. He even talked about writing an opera based on Samuel Beckett's play Waiting for Godot. None of these big projects were completed.

Boulez's Personality

When he was young, Boulez was known for being very direct and sometimes confrontational. One writer called him a "bully," and Boulez agreed, saying he had to fight against the old ways of society. For example, in 1952, he famously declared that any musician who hadn't truly experienced "dodecaphonic music" (twelve-tone music) was "USELESS."

However, those who knew him well often spoke of his loyalty. He helped his mentor, conductor Roger Désormière, after he became ill. A writer who observed Boulez later in life saw him caring about the health and families of musicians. In his later years, he was known for his charm and warmth. His humor was described as depending on his "twinkling eyes, his perfect timing, his infectious schoolboy giggle."

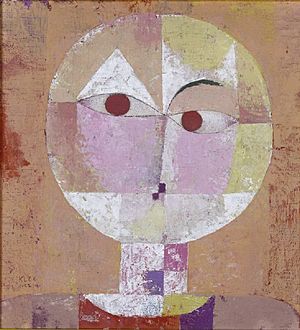

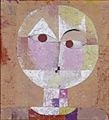

Boulez loved to read and was especially influenced by writers like Marcel Proust and James Joyce. He was also interested in visual arts throughout his life. He wrote about the painter Paul Klee and collected modern art. He knew artists like Joan Miró and Francis Bacon personally. He also had connections with important philosophers.

He enjoyed walking, especially in the Black Forest when he was at home in Baden-Baden. He also owned a farmhouse in France.

Boulez kept his private life very private. After his death, there was some discussion about his personal relationships, but little clear evidence exists. He had a personal assistant, Hans Messner, who lived with him and helped him with daily life.

One writer described Boulez as "affable, implacable, unknowable."

Boulez as a Conductor

Boulez was one of the top conductors of the second half of the 20th century. He led most of the world's major orchestras for over sixty years. He taught himself how to conduct, learning a lot by watching other conductors like Roger Désormière and Hans Rosbaud. He also mentioned George Szell as an important mentor.

Boulez gave different reasons for conducting so much. He started conducting for the Domaine musical because they didn't have much money, so he did it himself. He also said that conducting his own works was the best training for a composer. However, sometimes his conducting schedule made it hard to find time to compose.

Not everyone agreed on how great a conductor he was. Conductor Otto Klemperer called him "without doubt the only man of his generation who is an outstanding conductor and musician." Another critic, Hans Keller, felt Boulez sometimes missed the deeper meaning in older music. However, most agreed that Boulez conducted music he loved magnificently.

He worked with many leading soloists, including Daniel Barenboim and Jessye Norman.

Boulez was known for creating a clear, energetic sound. His precise rhythm could create a thrilling feeling. He was excellent at revealing the structure of a musical score and making complex orchestral sounds clear. He conducted without a baton and avoided dramatic movements. He believed that "outward excitement uses up inner excitement."

His ear for sound was legendary. There are many stories of him noticing a small mistake from an instrument in a large orchestra. Other conductors admired his clear and professional rehearsals. He was known for being very efficient and organized, knowing exactly what could and could not be done.

Boulez and Opera

Boulez also conducted in opera houses. He chose a small number of operas, focusing only on 20th-century works and Wagner. He enjoyed working with director Wieland Wagner on Wozzeck and Parsifal, finding their discussions about music and staging exciting.

They had planned other productions, but Wieland Wagner died in 1966. When Wozzeck was revived after Wagner's death, Boulez was very disappointed by the poor working conditions. This experience made him very critical of opera houses. In a famous interview, he even suggested that the "most elegant" solution for opera's problems would be "to blow the opera houses up."

Later, in the 1980s, Boulez became vice president of the planned Opéra Bastille in Paris. But when the music director, Daniel Barenboim, was fired, Boulez left in support.

Boulez only conducted opera projects when he was sure the conditions were right and he could work with top stage directors. Because of his years with the Barrault theater company, the visual and dramatic parts of an opera were as important to him as the music. He always attended staging rehearsals.

For the 1976 centenary Ring in Bayreuth, Boulez first asked other famous directors, but they refused. Finally, Patrice Chéreau, a theater director, accepted. He created one of the most important opera productions of modern times. Chéreau's production updated the story to the 19th and 20th centuries, using images from the industrial age. At first, the audience was hostile, and some musicians refused to work with Boulez later. But over the next four years, the production and music grew in fame. After the final performance in 1980, there was a 90-minute standing ovation. Boulez worked with Chéreau again on Berg's Lulu (1979) and Janáček's From the House of the Dead (2007).

His other favorite director was Peter Stein. Boulez believed Debussy's Pelléas et Mélisande was "not gentle at all, but cruel and mysterious." Stein's staging for Welsh National Opera in 1992 brought this vision to life. Their 1995 production of Schoenberg's Moses und Aron was described as "theatrically and musically thrilling."

From the mid-1960s, Boulez talked about composing an opera himself. He tried to find writers for the story, but they both passed away. He later discussed adapting a play by Jean Genet and another by Heiner Müller, but nothing came of these plans. In 2010, news came out that he was working on an opera based on Samuel Beckett's Waiting for Godot, but this ambitious project was never finished.

Boulez's Recordings

Boulez's first recordings were made in the late 1950s and early 1960s for the French Vega label. These included his early thoughts on works he would later re-record, as well as pieces he didn't record again. They also included the first of his five recordings of Le Marteau sans maître. In 2015, these early recordings were released together in a 10-CD set.

From 1966 to 1989, he recorded for Columbia Records (later Sony Classical). Among his first projects were the Paris Wozzeck and the London Pelléas et Mélisande. He made a highly praised recording of The Rite of Spring with the Cleveland Orchestra. He also recorded many works with the London Symphony Orchestra, including rare pieces and a complete set of Webern's works. He made a wide-ranging survey of Schoenberg's music, including large works like Gurrelieder. He also recorded the orchestral works of Ravel. For his own music, he recorded Pli selon pli, Rituel, and Éclat/Multiples. In 2014, Sony Classical released a 67-CD set of all his Columbia recordings.

Three of his opera projects from this period were released by other labels: the Bayreuth Ring on video and LP, and the Bayreuth Parsifal and Paris Lulu for Deutsche Grammophon.

In the 1980s, he also recorded for the Erato label, mostly with the Ensemble Intercontemporain. These recordings focused more on the music of his contemporaries and some of his own works. In 2015, Erato released a 14-CD set of his recordings for them. In 1984, he recorded some pieces on Frank Zappa's album The Perfect Stranger.

From 1991 onwards, Boulez recorded exclusively for Deutsche Grammophon. These recordings featured orchestras from Chicago, Cleveland, Vienna, and Berlin. He re-recorded much of his main repertoire, including the orchestral music of Debussy, Ravel, Stravinsky, and Bartók. He also oversaw a second complete set of Webern's works. His own later music, like Répons and sur Incises, was also featured. He recorded composers new to his list, such as Richard Strauss and Anton Bruckner. His recording of Bruckner's Eighth Symphony was especially praised. The most important addition to his recordings was a cycle of Gustav Mahler's symphonies and vocal works with different orchestras. An 88-disc set of all Boulez's recordings for Deutsche Grammophon, Philips, and Decca was released in 2022.

Many hundreds of concerts conducted by Boulez are also kept in the archives of radio stations and orchestras. In 2005, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra released a 2-CD set of his live broadcasts, including works he hadn't recorded commercially.

Boulez as a Performer

Early in his career, Boulez sometimes performed publicly as a pianist. In 1955, he played piano for a singer in a recording of songs by Stravinsky and Mussorgsky. From 1957 to 1959, he performed his own Third Piano Sonata several times. He also gave recitals of music for two pianos. In the 1960s and 1970s, he occasionally played piano for songs in orchestral concerts. A rare example of his piano playing later in life was a short film from 1992, where he played his early Notations.

Writing and Teaching

Boulez was one of the most prolific writers about music in the 20th century, similar to Schoenberg. Ironically, he first gained international attention as a writer with his 1952 article "Schoenberg is Dead," published shortly after Schoenberg's death. In this strong article, he criticized Schoenberg for being too traditional and praised Webern for being more radical.

Boulez's writings were for different audiences over the years. In the 1950s, he wrote for cultured Parisians. In the 1960s, he wrote for specialized avant-garde musicians. From 1976 to 1995, he wrote for a highly educated but non-specialist audience during his lectures at the Collège de France. Much of his writing was for specific events, like notes for a new piece or a recording. He generally avoided detailed musical analyses, except for one on The Rite of Spring. As one writer noted, Boulez was better at sharing ideas than technical information, which made his writing popular with non-musicians.

Boulez's writings have been published in English in several books. He also expressed his ideas through long interviews. Two volumes of his letters have been published: with composer John Cage and with anthropologist André Schaeffner.

Boulez taught at the Darmstadt Summer School almost every year from 1954 to 1965. He was a professor of composition in Switzerland from 1960 to 1963 and a visiting lecturer at Harvard University in 1963. He also gave private lessons early in his career. Some of his students became famous composers themselves.

Boulez's Impact

When Boulez turned 80, an article in The Guardian showed that other composers had mixed feelings about him:

- George Benjamin: Boulez created "wonderfully luminous and scintillating works" with "rigorous compositional skill" and "extraordinary aural refinement."

- Oliver Knussen: He was "a man who fashions his scores with the fanatical idealism of a medieval monk."

- John Adams: He was "a mannerist, a niche composer, a master who worked with a very small hammer."

- Alexander Goehr: "Boulez's failures will be better than most people's successes."

When Boulez died in January 2016, he did not leave a will. In 1986, he had agreed to place his musical and literary manuscripts with the Paul Sacher Foundation in Switzerland. In 2017, the Bibliothèque nationale de France announced that Boulez's family had donated many of his private papers and belongings, including books, archives, letters, scores, photos, and recordings.

In October 2016, the large concert hall of the Philharmonie de Paris was renamed the Grande salle Pierre Boulez. Boulez had campaigned for this hall for many years. In March 2017, a new concert hall, the Pierre Boulez Saal, designed by Frank Gehry, opened in Berlin. It is home to a new Boulez Ensemble.

Boulez's music continues to be performed by new generations of musicians. In September 2016, Simon Rattle and the Berlin Philharmonic performed Boulez's Éclat alongside Mahler's 7th Symphony on an international tour. In 2017, the Ensemble Intercontemporain performed Répons in New York. In September 2018, the first Pierre Boulez Biennial took place in Paris and Berlin, celebrating his music and the works that influenced him.

Awards and Honors

Boulez received many state honors, including Honorary Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) from the UK and the Knight Commander's Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany. Among his many awards, he listed: Grand Prix de la Musique (Paris, 1982), Polar Music Prize (Stockholm, 1996), Royal Philharmonic Society Gold Medal (1999), Wolf Prize (Israel, 2000), Grawemeyer Award for Music Composition (2001), Glenn Gould Prize (2002), and Kyoto Prize (Japan, 2009). He also received nine honorary doctorates from universities around the world.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Pierre Boulez para niños

In Spanish: Pierre Boulez para niños

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |