Edgard Varèse facts for kids

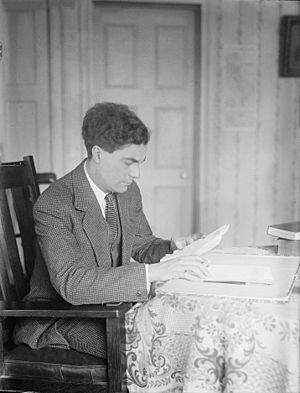

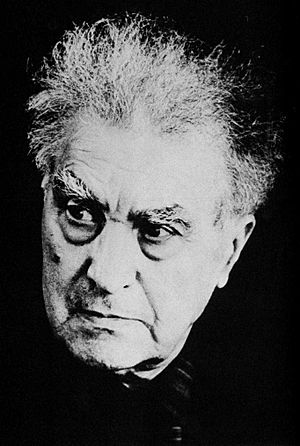

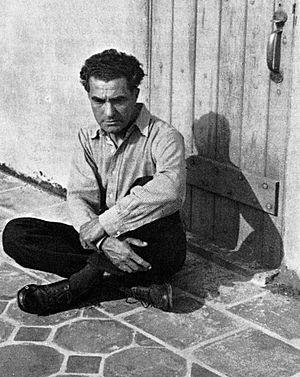

Edgard Varèse (born December 22, 1883 – died November 6, 1965) was a French composer who spent most of his life in the United States. Varèse's music focuses a lot on the timbre (the unique sound quality of an instrument) and rhythm. He even came up with the phrase "organized sound" to describe his own music style. He believed that music should be like "sound as living matter" and that "musical space" should be open and not limited.

Varèse thought of his music as "sound-masses", like how crystals form naturally. He once said that "to stubbornly conditioned ears, anything new in music has always been called noise", and he asked, "what is music but organized noises?"

Even though his complete surviving works only last about three hours, he greatly influenced many important composers of the late 20th century. Varèse saw a lot of potential in using electronic tools to make music. Because he used new instruments and electronic sounds, he became known as the "Father of Electronic Music." Writer Henry Miller even called him "The stratospheric Colossus of Sound."

Varèse also actively helped other 20th-century composers get their music performed. He started the International Composers' Guild in 1921 and the Pan-American Association of Composers in 1926.

Life and Music Journey

Early Years in France and Italy

Edgard Varèse was born in Paris, France. When he was just a few weeks old, he went to live with his great-uncle and other relatives in a small village called Le Villars in France. He grew very close to his grandfather, Claude Cortot, and felt more affection for him than for his own parents.

In the late 1880s, his parents brought him back, and in 1893, young Edgard had to move with them to Turin, Italy. His father was of Italian descent, and they wanted to live closer to his relatives. It was in Turin that he had his first real music lessons with Giovanni Bolzoni, who was the director of Turin's music school. In 1895, he wrote his first opera, Martin Pas, but this music is now lost.

As a teenager, Varèse's father, who was an engineer, wanted him to study engineering. So, Varèse enrolled at the Polytechnic of Turin. His father did not approve of his interest in music and wanted him to focus only on engineering. This disagreement grew stronger, especially after his mother passed away in 1900. Finally, in 1903, Varèse left home and moved to Paris.

In 1904, he began studying music at the Schola Cantorum, where one of his teachers was Albert Roussel. After that, he studied composition with Charles-Marie Widor at the Paris Conservatoire. During this time, he wrote several big orchestral pieces, but he only performed them himself on the piano. One of these was his Rhapsodie romane from around 1905, which was inspired by the old churches in Tournus. In 1907, he moved to Berlin and married actress Suzanne Bing. They had a daughter but divorced in 1913.

During these years, Varèse met famous composers like Erik Satie, Richard Strauss, Claude Debussy, and Ferruccio Busoni. These composers greatly influenced him. He also became friends with Romain Rolland and Hugo von Hofmannsthal. On January 5, 1911, his musical piece Bourgogne was performed for the first time in Berlin.

After being released from the French Army during World War I due to injury, he moved to the United States in December 1915.

Starting Fresh in the United States

In 1918, Varèse made his first appearance in America by conducting a large musical work by Berlioz.

He spent his first few years in the United States in Greenwich Village, New York City. He met many important American musicians and promoted his ideas for new electronic musical instruments. He also conducted orchestras and started a short-lived group called the New Symphony Orchestra. In New York, he met Leon Theremin, who invented an early electronic instrument, and other composers who were exploring new electronic sounds.

Around this time, Varèse began working on his first composition in the United States, Amériques. He finished it in 1921, but it wasn't performed until 1926 by the Philadelphia Orchestra. Almost all the music he had written in Europe was lost or destroyed in a fire in Berlin. So, in the U.S., he had to start all over again. The only piece that survived from his early period was a song called Un grand sommeil noir.

After finishing Amériques, Varèse and Carlos Salzedo started the International Composers' Guild (ICG). This group was dedicated to performing new music by both American and European composers. In July 1921, the ICG announced, "The present day composers refuse to die. They have realised the necessity of banding together and fighting for the right of each individual to secure a fair and free presentation of his work." In 1922, Varèse visited Berlin and helped start a similar group there with Ferruccio Busoni.

Varèse wrote many of his pieces for orchestral instruments and voices to be performed by the ICG during its six years. In the early 1920s, he composed Offrandes, Hyperprism, Octandre, and Intégrales.

He became an American citizen in October 1927. After coming to the USA, Varèse often used 'Edgar' for his first name, but he started using 'Edgard' again, though not always, from the 1940s.

Return to Paris and New Sounds

In 1928, Varèse went back to Paris to change a part in his piece Amériques to include the recently invented ondes Martenot, an early electronic instrument. Around 1930, he composed Ionisation, which was the first classical music piece to feature only percussion instruments. Even though it used existing instruments, Ionisation was all about exploring new sounds and ways to create them.

In 1931, he was the best man at his friend Nicolas Slonimsky's wedding in Paris. In 1933, while still in Paris, he wrote to the Guggenheim Foundation and Bell Laboratories asking for money to build an electronic music studio. His next composition, Ecuatorial, was finished in 1934. It included parts for two special electronic instruments called fingerboard Theremin cellos, along with winds, percussion, and a bass singer. Varèse was excited about getting a grant and quickly returned to the United States to work on his electronic music. Slonimsky conducted the first performance of Ecuatorial in New York on April 15, 1934.

Back in the United States Again

Varèse soon left New York City and traveled to Santa Fe, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. In 1936, he wrote his solo flute piece, Density 21.5. He also promoted the theremin during his travels in the Western U.S. and demonstrated one at a lecture in New Mexico in 1936. By the time Varèse returned to New York in late 1938, Leon Theremin had gone back to Russia. This made Varèse very sad, as he had hoped to work with him to improve the instrument.

Later, in the late 1950s, when a publisher wanted to make Ecuatorial available, there were very few theremins around. So, Varèse rewrote the part for the ondes Martenot instead. This new version was performed for the first time in 1961.

Science and Sound Ideas

When Varèse lived with his father, an engineer, he was encouraged to study science at a high school in Italy that focused on math and science. Here, Varèse became very interested in the works of Leonardo da Vinci.

Varèse began his music studies in Paris from 1903 to 1905. While in Paris, Varèse had a very important experience during a performance of Beethoven's Seventh Symphony. During one part of the music, perhaps because of how the hall sounded, Varèse felt like the music was breaking apart and moving through space. This idea stayed with him for the rest of his life. He later described it as "sound objects, floating in space."

Unfinished Big Projects

From the late 1920s to the end of the 1930s, Varèse put most of his creative energy into two big projects that were never finished. Much of the music for these projects was destroyed, but some ideas from them might have been used in his smaller works. One was a large stage show called The One-All-Alone or Astronomer. This was first planned to be based on Native American legends. Later, it became a futuristic story about a world disaster and instant communication with the star Sirius. Varèse worked on this second version in Paris from 1928 to 1932.

The second big project was a choral symphony called Espace. At first, the words for the chorus were to be written by André Malraux. Later, Varèse decided on a text with important phrases in many languages, to be sung by choirs in Paris, Moscow, Beijing, and New York City. These choirs would be synchronized to create a global radio event. Varèse asked writer Henry Miller for ideas for the text. Miller suggested that this grand idea, which also never happened, eventually turned into Varèse's piece Déserts. Varèse felt frustrated with both these huge projects because he lacked the electronic instruments he needed to create the sounds he imagined.

However, he used some of the material from Espace in his short piece Étude pour espace, which was almost the only new work he had written in over ten years when it premiered in 1947.

Becoming Famous Worldwide

By the early 1950s, Varèse was talking with a new generation of composers. When he went back to France to finish the tape parts for Déserts, Pierre Schaeffer helped him find the right facilities. The first performance of Déserts, which combined orchestral music with tape sounds, was part of a radio concert. It was played between pieces by Mozart and Tchaikovsky and received a strong, mixed reaction from the audience.

Le Corbusier, a famous architect, was hired by Philips to design a building for the 1958 World Fair. He insisted on working with Varèse, even though the sponsors resisted. Varèse created his Poème électronique for this building, where about two million people heard it. Using 400 speakers placed throughout the building, Varèse made a sound and space experience where listeners could feel the sound moving through space. This piece challenged what people expected from music and how it was composed, bringing new life to electronic sound and presentation.

In 1962, he was invited to join the Royal Swedish Academy of Music, and in 1963, he received a major music award called the Koussevitzky International Recording Award.

In 1965, Edgard Varèse received the Edward MacDowell Medal.

Musical Influences

In his younger years, Varèse was very impressed by Medieval and Renaissance music. Later in his career, he even started and conducted several choirs that performed this older music. He was also influenced by the music of Alexander Scriabin, Erik Satie, Claude Debussy, Hector Berlioz, and Richard Strauss. You can also hear clear influences from Stravinsky's early works, like Petrushka and The Rite of Spring, in Varèse's piece Arcana.

Students and Impact

Students

Varèse taught many important composers, including Chou Wen-chung, Lucia Dlugoszewski, André Jolivet, Colin McPhee, James Tenney, and William Grant Still. See: List of music students by teacher: T to Z#Edgard Varèse.

Influence on Classical Music

Many composers have said they were influenced by Varèse, or you can see his influence in their music. These include Pierre Boulez, John Cage, Olivier Messiaen, Karlheinz Stockhausen, and Iannis Xenakis.

The conductor of modern music, Robert Craft, recorded two albums of Varèse's music in 1958 and 1960. These recordings helped Varèse gain wide attention among musicians and music lovers beyond his immediate circle. Much of the percussion music by George Crumb, for example, owes a lot to Varèse's works like Ionisation and Intégrales.

Influence on Popular Music

Varèse's focus on timbre (sound quality), rhythm, and new technologies inspired many musicians who grew up in the 1960s and 1970s. One of Varèse's biggest fans was the American guitarist and composer Frank Zappa. When Zappa heard an album called The Complete Works of Edgard Varèse, Vol. 1, he became obsessed with the composer's music.

On Zappa's 15th birthday, December 21, 1955, his mother let him make an expensive long-distance call to Varèse's home in New York City. Varèse was away in Brussels, Belgium, so Zappa spoke to Varèse's wife, Louise. Eventually, Zappa and Varèse talked on the phone and discussed meeting. Although they never met, Zappa received a letter from Varèse. Zappa framed this letter and kept it in his studio for the rest of his life. Varèse's spirit of trying new things and pushing the boundaries of music lived on in Zappa's long and successful career. Zappa's last project was a recording of Varèse's works.

Tributes

- The record label Varèse Sarabande Records is named after him.

- Keyboard player Robert Lamm from the band Chicago wrote a song called "A Hit By Varèse" for their album Chicago V (1972).

- American saxophonist and composer John Zorn was inspired by Varèse for his 2006 album Moonchild: Songs Without Words.

Musical Ideas

Predictions

Varèse often thought about how technology would change music in the future. In 1936, he predicted musical machines that could play music as soon as a composer put in their score. He said these machines would be able to play "any number of frequencies," meaning many different pitches. Therefore, the music score of the future would need to be like a "seismograph" to show all its possibilities. In 1939, he added that with this machine, "anyone will be able to press a button to release music exactly as the composer wrote it—exactly like opening up a book." Varèse didn't see these predictions fully come true until his experiments with tape recordings in the 1950s and 1960s.

Idée fixe

Some of Edgard Varèse's works, especially Arcana, use something called an idée fixe. This is a fixed musical theme that is repeated several times in a piece. The idée fixe was famously used by Hector Berlioz in his Symphonie fantastique. It's usually not changed in pitch, which makes it different from a leitmotiv used by Richard Wagner.

Works

- Un grand sommeil noir, song for voice and piano (1906)

- Amériques for large orchestra (1918–1921; revised 1927)

- Offrandes for soprano and chamber orchestra (1921)

- Hyperprism for wind and percussion (1922–1923)

- Octandre for seven wind instruments and double bass (1923)

- Intégrales for wind and percussion (1924–1925)

- Arcana for large orchestra (1925–1927)

- Ionisation for 13 percussion players (1929–1931)

- Ecuatorial for bass voice, brass, organ, percussion and theremins (revised for ondes-martenots in 1961) (1932–1934)

- Density 21.5 for solo flute (1936)

- Étude pour espace for soprano solo, chorus, 2 pianos and percussion (1947)

- Dance for Burgess for chamber ensemble (1949)

- Déserts for wind, percussion and electronic tape (1950–1954)

- La procession de verges for electronic tape (soundtrack for a film) (1955)

- Poème électronique for electronic tape (1957–1958)

- Nocturnal for soprano, male chorus and orchestra (1961)

|

See also

In Spanish: Edgar Varèse para niños

In Spanish: Edgar Varèse para niños