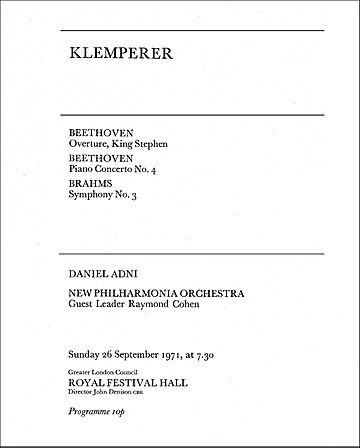

Otto Klemperer facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Otto Klemperer

|

|

|---|---|

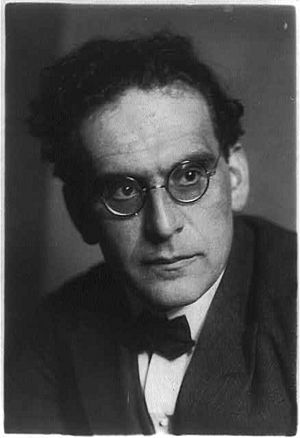

Klemperer, circa 1920

|

|

| Born | 14 May 1885 |

| Died | 6 July 1973 (aged 88) Zürich, Switzerland

|

| Citizenship | German (1885–1935) American (1940–1954) German (1954–1973) Israeli (joint nationality, 1970–1973) |

| Occupation | Conductor, composer |

| Spouse(s) |

Johanna Geisler

(m. 1919, died 1956) |

| Children | Werner and Lotte Klemperer |

Otto Nossan Klemperer (May 14, 1885 – July 6, 1973) was a famous conductor and composer. He was born in Germany. Later, he worked in the US, Hungary, and finally Britain. At first, he led music in opera houses. But he became best known for conducting orchestras in concert halls.

Otto Klemperer was a student and friend of the famous composer Gustav Mahler. From 1907, Klemperer got more and more important jobs. He led music in opera houses across Germany. From 1929 to 1931, he was in charge of the Kroll Opera in Berlin. There, he showed new musical works. He also put on classic operas in new, modern ways.

Klemperer came from a Jewish family. When the Nazis came to power in 1933, he had to leave Germany. Soon after, he became the main conductor of the Los Angeles Philharmonic orchestra. He also led other American orchestras as a guest. These included the San Francisco Symphony and the New York Philharmonic.

In the late 1930s, Klemperer became very ill. He had a brain tumor. Doctors removed it, but the surgery left him partly paralyzed on his right side. He also had a mood disorder that affected his feelings and behavior. This illness made his career difficult for a while. He did not fully recover until the mid-1940s. From 1947 to 1950, he was the music director of the Hungarian State Opera in Budapest.

Klemperer's later career was mostly in London. In 1951, he started working with the Philharmonia Orchestra. By then, he was known for his strong performances of German symphonies. He gave many concerts and made nearly 200 recordings with the Philharmonia. He retired in 1972. Some people thought his style for Mozart was too serious. But many believed he was the best at conducting symphonies by Beethoven, Brahms, Bruckner, and Mahler.

Contents

Life and Career of Otto Klemperer

Early Life and Musical Training

Otto Nossan Klemperer was born on May 14, 1885. His birthplace was Breslau, in what was then the German Empire. Today, this city is called Wrocław, and it is in Poland. Otto was the second child and only son of Nathan and Ida Klemperer. His family name was changed to Klemperer in 1787. This was part of an effort to help Jewish families fit into Christian society. Both of Otto's parents loved music. His father sang, and his mother played the piano.

When Otto was four, his family moved to Hamburg. His mother gave piano lessons there. It was decided early on that Otto would become a professional musician. He started piano lessons with his mother around age five. He later studied piano at the Hoch Conservatory in Frankfurt. He also learned music theory there. Klemperer followed his piano teacher, James Kwast, to Berlin. He later said Kwast taught him everything important about music. Another teacher, Hans Pfitzner, taught him how to compose and conduct.

In 1905, Klemperer met Gustav Mahler in Berlin. Mahler was a very famous composer and conductor. Klemperer helped with a rehearsal of Mahler's Second Symphony. Later, Klemperer made a piano version of the symphony. He played it for Mahler in 1907. Klemperer first conducted in public in May 1906. He took over a show called Orpheus in the Underworld in Berlin.

Mahler wrote a short note recommending Klemperer. Klemperer kept this note his whole life. Because of it, he got a job in Prague in 1907. He became a chorus master and assistant conductor there.

Leading German Opera Houses

After Prague, Klemperer worked at the Hamburg State Opera from 1910 to 1912. Then he became the main conductor in Barmen (1912–1913). After that, he moved to the larger Strasbourg Opera (1914–1917). From 1917 to 1924, he was the chief conductor of the Cologne Opera.

In Cologne, he married Johanna Geisler in 1919. She was a singer in the opera company. Otto converted from Judaism to Roman Catholicism at this time. He remained Catholic until 1967, when he returned to Judaism. Otto and Johanna had two children. Their son, Werner, became an actor. Their daughter, Lotte, became her father's assistant. Johanna continued her singing career, sometimes with Otto conducting. She stopped singing in the mid-1930s. They stayed close until she died in 1956.

In 1923, Klemperer turned down a job at the Berlin State Opera. He felt he would not have enough artistic control there. The next year, he became a conductor at the Prussian State Theatre in Wiesbaden (1924–1927). This was a smaller theater. But he had the control he wanted over the shows. He conducted many operas there. These included The Marriage of Figaro, Don Giovanni, and Fidelio. He also led more modern works. He later said this was the happiest time of his career.

Klemperer visited Russia in 1924 and conducted there. He returned every year until 1936. In 1926, he made his first appearance in America. He was a guest conductor for the New York Symphony Orchestra. During his eight weeks, he led the first US performances of Mahler's Ninth Symphony. He also conducted Janáček's Sinfonietta.

Working in Berlin

In 1927, Berlin leaders decided to start a new opera company. It would focus on new works and fresh productions. This company was known as the Kroll Opera. Klemperer was chosen to be its first director. He signed a ten-year contract. He agreed on the condition that he could also conduct concerts. He also wanted to choose his own stage designers.

Klemperer's time at the Kroll Opera was very important for his career. It also helped shape opera in the early 20th century. He introduced many new musical pieces. He said the most important operas he showed there were by Stravinsky, Krenek, Hindemith, Janáček, and Schoenberg.

The Kroll Opera used modern ways of staging shows. For example, in 1929, they put on Der fliegende Holländer in a very new style. This was different from old-fashioned sets and costumes. Some critics loved it, saying it was "unusual and magnificent." Others hated it, calling it "a new outrage."

In 1929, Klemperer conducted in Britain for the first time. He led the London Symphony Orchestra. He was praised for his "dominating personality" and "masterful control." Critics called him "a great orchestral commander."

The Kroll Opera closed in 1931. The official reason was money problems. But Klemperer believed it was for political reasons. He was told that his "political and artistic direction" was not liked. Klemperer had to move to the main State Opera. But there was little important work for him there. He stayed until 1933. Then, the rise of the Nazis forced him to leave Germany for Switzerland. His wife and children joined him.

Moving to Los Angeles

After leaving Germany, Klemperer found it hard to get conducting jobs. He did get some important chances in Vienna and at the Salzburg Festival. Then, William Andrews Clark, who started the Los Angeles Philharmonic, asked Klemperer to be their main conductor. The Los Angeles orchestra was not considered one of the best in America. The pay was also less than Klemperer wanted. But he accepted and moved to the US in 1935.

The orchestra had money troubles. Clark had lost much of his wealth during the Great Depression. Still, Klemperer successfully introduced new music. This included Mahler's Das Lied von der Erde and Bruckner's symphonies. He also played music by his neighbor, Arnold Schoenberg. Schoenberg also gave Klemperer lessons in composing music. Klemperer thought Schoenberg was the best composition teacher.

In 1935, Klemperer conducted the New York Philharmonic for four weeks. The audience in New York was very traditional. Klemperer insisted on playing Mahler's Second Symphony. Critics praised his conducting. But ticket sales were low. Klemperer hoped to become the orchestra's main conductor. But he knew the Mahler symphony had hurt his chances.

Back in Los Angeles, Klemperer conducted the orchestra in many cities. He worked with famous solo musicians. He also exchanged conducting jobs with Pierre Monteux, who led the San Francisco Symphony. After a concert in 1936, a critic called Klemperer one of the world's greatest conductors.

From 1938 to 1945

In 1938, the Pittsburgh Symphony asked Klemperer for help. They wanted to become a full-time orchestra again. Klemperer held auditions and rehearsed the musicians. The first concerts were very successful. He was offered a high salary to stay. But he was already committed to Los Angeles. So, Fritz Reiner became the conductor in Pittsburgh.

In 1939, Klemperer started having serious balance problems. Doctors found a brain tumor. He had surgery in Boston, which was successful. But it left him partly paralyzed on his right side. He also had a mood disorder. After the surgery, he went through a difficult period with his illness. In 1941, he left a mental health center. The police looked for him, describing him as "dangerous." He was found two days later and seemed calm. A doctor said he was "temperamental" but not dangerous. The Los Angeles orchestra ended his contract. He had few conducting jobs after that. His daughter, Lotte, worked in a factory to help the family.

After the War

By 1946, Klemperer was healthy enough to conduct in Europe again. His first concert was in Stockholm. In 1947, he conducted operas in Salzburg and Vienna. While in Salzburg, he was invited to be the music director of the Hungarian State Opera in Budapest. He accepted this job and worked there from 1947 to 1950. In Budapest, he conducted many operas by Mozart and others. He also led many concerts.

In March 1948, Klemperer performed in London for the first time since the war. He conducted the Philharmonia Orchestra. He led works by Bach, Stravinsky, and Beethoven.

Klemperer left Budapest in 1950. He was frustrated by political interference from the communist government. For the next nine years, he did not have a permanent conducting job. In the early 1950s, he worked as a guest conductor in many countries. In London in 1951, he conducted two Philharmonia concerts. Critics praised him highly. The Times newspaper said his conducting showed "emotional intensity" and "intellectual force."

After this, Klemperer faced another setback. In 1951, he fell on ice at a Montreal airport and broke his hip. He was in the hospital for eight months. Then, for a year, he and his family had trouble leaving the US. This was due to new laws. With help, he got temporary passports in 1954. He moved with his wife and daughter to Switzerland. He settled in Zürich and got German citizenship again.

Working in London

From the mid-1950s, Klemperer lived in Zürich. But his main musical work was in London. There, he became closely linked with the Philharmonia Orchestra. This orchestra was seen as the best in Britain in the 1950s. Its founder, Walter Legge, hired many top conductors. Legge wanted Klemperer to work with the Philharmonia more often. The musicians, critics, and public all admired Klemperer.

Legge also worked for EMI, a recording company. He often planned concerts using music that had just been recorded. This meant the orchestra was well-rehearsed. Klemperer liked this because it gave him "time to prepare a work properly."

By this time, Klemperer's music choices had changed. He no longer focused on experimental modern music. Instead, he focused on German classical and romantic composers. Bach and Beethoven were at the center of his work. Critics praised his Beethoven performances. They noted their "spacious, perfectly proportioned architecture" and "majesty of line."

In 1957, Legge started the Philharmonia Chorus. They first performed Beethoven's Ninth Symphony with Klemperer. A critic wrote that London now had "a Beethoven cycle that any city in the world would envy."

Klemperer was invited to conduct at the 1959 Holland Festival. But he had another accident. In October 1958, he set his bedclothes on fire while smoking in bed. He suffered severe burns. His recovery was slow. He could not conduct again until September 1959. When he returned to the Philharmonia, Walter Legge named him the orchestra's first principal conductor for life. In the 1960s, Klemperer conducted more works outside the main German music. These included pieces by Bartók, Berlioz, and Tchaikovsky.

Klemperer returned to opera in 1961. He made his debut at Covent Garden with Fidelio. He directed the staging and conducted the music. This production was seen as "traditional, unfussy, grandly conceived." He also directed and conducted Fidelio in Zürich the next year. At Covent Garden, he later directed and conducted Die Zauberflöte (1962) and Lohengrin (1963).

Later Years and Retirement

In the early 1960s, Walter Legge became unhappy with the music scene. In March 1964, he announced that the Philharmonia Orchestra would stop its activities. Klemperer said Legge did not warn him. But with Klemperer's strong support, the musicians refused to break up. They formed their own group, the New Philharmonia Orchestra (NPO). They chose Klemperer as their president. He stayed in this role until he retired eight years later.

In his later years, Klemperer returned to the Jewish faith. He strongly supported the country of Israel. He visited his younger sister there. In 1970, he accepted Israeli citizenship. He also kept his German citizenship and Swiss residency.

As Klemperer got older, his focus and control of the orchestra lessened. Sometimes, he would fall asleep while conducting. His hearing and eyesight also became weaker. But musicians said that suddenly, he would become "wonderfully vigorous again." Klemperer continued to conduct and record with the New Philharmonia. His last concert was on September 26, 1971. His final recording session was two days later.

In January 1972, Klemperer announced he could no longer handle public performances. He hoped to keep making recordings. But these plans did not happen. He retired to his home in Zürich. He died in his sleep on July 6, 1973. He was buried in the Jewish cemetery in Zürich.

Otto Klemperer's Compositions

Klemperer once said, "I am mainly a conductor who also composes." He wished to be remembered as both. In his time, conductors were expected to compose music. He started composing at a young age. He wrote songs in his mid-teens. He often changed his compositions and destroyed some.

In 1908, Klemperer heard Debussy's opera Pelléas et Mélisande. This changed his ideas about composing. He felt the music he wrote after that was his first mature work. He continued to write about 100 songs. Around 1915, he wrote two operas. Neither was performed in public. But he did conduct a private concert of one opera in 1931. The "Merry Waltz" from this opera is his best-known composition. He wrote nine string quartets, and eight of them still exist.

Klemperer conducted the first performance of his First Symphony in 1961. He conducted the final version of his Second Symphony in 1969. He recorded it a few weeks later. He wrote six symphonies in total. Critics had different opinions about his compositions. Some found his fast music "gritty." Others found his slow movements "astonishingly sweet." One critic said his Second Symphony was "the product of an outstanding conductor."

Recordings by Otto Klemperer

Otto Klemperer did not enjoy making recordings. But he made many of them. His first recording was in 1924. It was a part of Bruckner's Eighth Symphony. He made it for Polydor with the Staatskapelle Berlin. His early recordings included Beethoven symphonies. He also recorded music by Ravel and Debussy. He recorded German classics like Brahms and Wagner. He even recorded lighter French music.

From his years in Los Angeles, there is only one studio recording. But there are several recordings from live radio shows. These include symphonies by Beethoven and Dvořák. They also have parts of operas by Gounod and Verdi. There are no studio recordings from his time in Budapest. But live performances were recorded. These include complete operas like Lohengrin and The Magic Flute. All were sung in Hungarian.

In 1951, Klemperer recorded several works in Vienna for the Vox label. These included Beethoven's Missa solemnis. This recording was praised as "grave and powerful." That same year, his live performances of Mahler's Kindertotenlieder were recorded.

In October 1954, Klemperer made his first recording with the Philharmonia Orchestra. It was Mozart's Jupiter Symphony. Critics called it "extremely impressive." Between 1954 and 1972, he recorded nearly 200 different works with the Philharmonia. These included more Mozart symphonies. He also recorded complete symphony sets by Beethoven and Brahms. Other works were by Bach, Richard Strauss, and Wagner.

With the Philharmonia Chorus and Orchestra, he recorded Bach's St Matthew Passion. He also recorded Handel's Messiah and Brahms's German Requiem. His complete opera recordings with the Philharmonia were Fidelio and The Magic Flute.

After the musicians formed the New Philharmonia in 1964, Klemperer continued recording with them. He recorded symphonies by Haydn, Schumann, Bruckner, and Mahler. He also recorded all of Beethoven's piano concertos. Daniel Barenboim was the soloist. Major choral recordings included Beethoven's Missa solemnis and Bach's B minor Mass. Critics praised the Missa solemnis as one of the greatest recordings. He also recorded four complete operas: Così fan tutte, Don Giovanni, Der fliegende Holländer, and The Marriage of Figaro.

Honors and Legacy

Awards and Recognition

In 1933, Klemperer received the Goethe Medal in Berlin. In 1966, he won the Leipzig Orchestral Nikisch Prize. He also received honorary degrees from two universities in California. In 1971, he became an honorary member of the Royal Academy of Music in London. From Germany, he received the Grand Medal of Merit with Star (1958) and the Order of Merit (1967).

The first part of Klemperer's 1959 recording of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony was chosen by NASA. It was put on the Voyager Golden Record. This record was sent into space on the Voyager space craft. It contained sounds and images to show life and culture on Earth.

In 1973, Lotte Klemperer gave the Royal Academy of Music a collection of her father's books and music scores. She also gave them a portrait and some of his conducting sticks. This is now called the Otto Klemperer Collection. One of the academy's conducting professorships is named the Klemperer Chair.

His Reputation as a Conductor

When Klemperer died, a music critic wrote that an "age of giants has ended." He listed other great conductors who were gone. The Times newspaper said that in Britain, Klemperer was seen as the greatest living conductor. Many people agreed that he was the most important conductor for German and Austrian classical music.

Many musicians had different opinions about Klemperer's way of conducting Mozart. One critic said Klemperer's Mozart was "made of sterner stuff." Another complained that his direction of The Marriage of Figaro was "humourless." But others found his slow and calm view of the opera interesting. Klemperer's slow speeds sometimes drew criticism in his later years. But an EMI producer said Klemperer's tempos were always carefully chosen. They were part of his overall understanding of the music.

Critics wished Klemperer had conducted more of Bruckner's symphonies. They said he understood these works deeply. Some noted that in his later years, his conducting became very firm. He was not known for colorful sounds. Instead, his music often had a clear, almost black-and-white tone.

Klemperer was most famous as a Beethoven conductor. His 1951 recording of the Missa solemnis was called "sublime." His recording of the Fifth Symphony was seen as "individual" and "illuminating." A critic wrote that his 1962 recording of Fidelio was "stunning." Alan Civil, the Philharmonia's first horn player, said Klemperer brought new understanding to Beethoven. He felt it was "as though Beethoven himself were standing there."

See also

In Spanish: Otto Klemperer para niños

In Spanish: Otto Klemperer para niños

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |