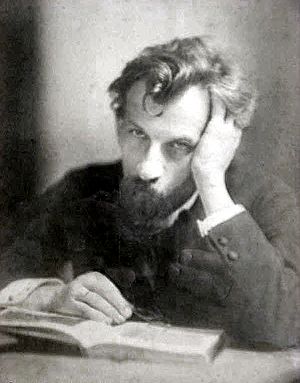

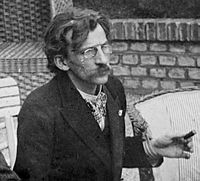

Hans Pfitzner facts for kids

Hans Erich Pfitzner (born May 5, 1869 – died May 22, 1949) was a German composer and conductor. He was known for being against modern music styles. His most famous work is the opera Palestrina (1917). This opera is loosely based on the life of a famous 16th-century composer named Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina.

Contents

Life

Hans Pfitzner was born in Moscow. His father played the cello in an orchestra there. In 1872, when Hans was two, his family moved back to his father's hometown, Frankfurt, in Germany. Pfitzner always thought of Frankfurt as his true home.

He learned to play the violin from his father at a young age. He started writing his own music when he was 11. In 1884, he wrote his first songs. From 1886 to 1890, he studied music at the Hoch Conservatory in Frankfurt. He learned composition with Iwan Knorr and piano with James Kwast. Later, Pfitzner married Kwast's daughter, Mimi.

Pfitzner worked several low-paying jobs early in his career. He taught piano and music theory at the Koblenz Conservatory from 1892 to 1893. In 1894, he became a conductor at the Staatstheater Mainz for a few months. When he was almost 40, in 1908, he got a more important job. He became the opera director and head of the conservatory in Straßburg (Strasbourg).

In Strasbourg, Pfitzner finally had a steady job. He gained more control over his own operas. He believed that he should be in charge of how his operas were performed on stage. This idea caused him problems later in his career. A big change in Pfitzner's life happened after World War I. France took over Strasbourg in 1918. Pfitzner lost his job and became very poor at age 50.

This made some of his personality traits stronger. He felt he deserved special treatment for his contributions to German art. He was often socially awkward and not very polite. He truly believed his music was not appreciated enough. He also felt personally wronged by Germany's enemies. His sadness grew in the 1920s after his wife died in 1926. His older son, Paul, also became ill and needed special medical care.

In 1895, Richard Bruno Heydrich sang the main role in Pfitzner's first opera, Der arme Heinrich. People said Heydrich "saved" the opera. Pfitzner's most important work was Palestrina. It was first performed in Munich on June 12, 1917. The conductor was Bruno Walter. Walter, a famous conductor, believed Palestrina would be remembered forever.

One of Pfitzner's most famous writings was a pamphlet called Futuristengefahr (which means "Danger of Futurists"). He wrote it to respond to another musician, Ferruccio Busoni. Busoni thought that the future held all the hope for Western music. Pfitzner disagreed, asking, "What if we are already at a high point, or have even passed it?" Pfitzner had similar discussions with other music critics.

Pfitzner dedicated his Violin Concerto in B minor, Op. 34 (1923), to the Australian violinist Alma Moodie. She performed it for the first time in Nuremberg in 1924, with Pfitzner conducting. Moodie became very well known for playing this piece. She performed it over 50 times in Germany. At that time, Pfitzner's concerto was seen as a very important new violin piece. However, it is not played as often by violinists today.

The Nazi Era

As he got older, Pfitzner became more nationalistic. At first, some important people in Nazi Germany liked him. But he soon had disagreements with the main Nazi leaders. They didn't like his long friendship with the Jewish conductor Bruno Walter. Pfitzner also made the Nazis angry when he refused to write music for Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream. The Nazis wanted him to replace the famous music by Felix Mendelssohn, who was Jewish. Pfitzner said that Mendelssohn's original music was much better than anything he could create.

Pfitzner and Hitler met as early as 1923. Pfitzner was in the hospital after an operation. Hitler did most of the talking. Pfitzner disagreed with him about a certain thinker, which made Hitler leave angrily. Later, Hitler said he wanted "nothing further to do with this Jewish rabbi" about Pfitzner. Pfitzner didn't know about this comment and thought Hitler liked him.

When the Nazis came to power in 1933, Pfitzner was asked to give lectures. He accepted, hoping it would help him get an important job. However, Hitler made sure that Pfitzner was not chosen for important positions. These jobs went to people who were more loyal to the Nazi party.

In 1934, Pfitzner was forced to retire. He lost his jobs as an opera conductor, stage director, and professor. He also received a very small pension. He fought this until 1937 when the issue was finally resolved. For a Nazi party event in 1934, Pfitzner hoped to conduct. But he was rejected. At the event, he learned for the first time that Hitler believed he was partly Jewish. Pfitzner had to prove that his family was not Jewish. By 1939, he was very unhappy with the Nazi government.

Pfitzner's ideas about Jewish people were confusing. He thought of Jewishness as a cultural thing, not a race. In 1930, he said that while Jewish people might pose "dangers to German spiritual life," many Jews had done a lot for Germany. He also said that hating Jewish people was wrong. He was willing to make exceptions. For example, he helped his Jewish student Felix Wolfes. He also stayed friends with Bruno Walter and his childhood friend Paul Cossman, who was Jewish.

Pfitzner's efforts to help Cossman might have caused the Gestapo (Nazi secret police) to investigate him. Pfitzner's requests probably helped Cossman be released in 1934. However, Cossman was later arrested again in 1942 and died in Theresienstadt. Pfitzner worked with Jewish musicians throughout his career. He often performed with the famous singer Ottilie Metzger-Lattermann, who was later killed in Auschwitz. Still, Pfitzner also kept in touch with people who strongly disliked Jewish people. He sometimes used hateful language, which was common among people of his generation.

Pfitzner's home was destroyed by bombs during the war. His membership in the Munich Academy of Music was taken away because he spoke out against Nazism. In 1945, he was homeless and mentally ill. But after the war, he was cleared of Nazi ties and given his pension back. He was allowed to live in an old people's home in Salzburg. He died there in 1949.

After a long time of being forgotten, Pfitzner's music started to be performed again in the 1990s. Many music experts, especially in Germany and Britain, began to study Pfitzner's life and music. They looked at his complex relationship with the Nazis. Some concluded that he was not fully pro-Nazi. He worked with Nazi leaders hoping they would promote his music. But he became bitter when the Nazis found his music not useful for their propaganda.

Students of Hans Pfitzner

- Sem Dresden (1881–1957)

- Ture Rangström (1884–1947)

- Otto Klemperer (1885–1973)

- W. H. Hewlett (1873–1940)

- Heinrich Jacoby (1889–1964)

- Czesław Marek (1891–1985)

- Charles Münch (1891–1968)

- Felix Wolfes (1892–1971)

- Carl Orff (1895–1982)

- Heinrich Sutermeister (1910–1995)

Recordings

All of Pfitzner's orchestral works have been recorded by the German conductor Werner Andreas Albert. His complete songs have also been recorded. His chamber music, which includes string quartets, piano trios, and a violin sonata, has been recorded many times.

Works

Operas

| Title | Year | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Der arme Heinrich | 1891–1893 | His first opera. |

| Die Rose vom Liebesgarten | 1897–1900 | A romantic opera. |

| Das Christ-Elflein (1st version) | 1906 | A Christmas story. |

| Das Christ-Elflein (2nd version) | 1917 | A revised version of the Christmas opera. |

| Palestrina | 1909–1915 | His most famous work. |

| Das Herz | 1930–31 | A drama for music. |

Orchestral Works

| Work | Year | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Scherzo in C minor | 1887 | |

| Cello Concerto in A minor | 1888 | |

| Incidental music to Das Fest auf Solhaug | 1890 | Music for a play by Henrik Ibsen. |

| Herr Oluf | 1891 | A ballad for baritone and orchestra. |

| Die Heinzelmännchen | 1902-03 | A ballad for bass and orchestra. |

| Das Käthchen von Heilbronn | 1905 | Incidental music for a play. |

| Piano Concerto in E-flat major | 1922 | |

| Violin Concerto in B minor | 1923 | Dedicated to Alma Moodie. |

| Lethe | 1926 | For baritone and orchestra. |

| Symphony in C-sharp minor | 1932 | Adapted from his String Quartet, Op. 36. |

| Cello Concerto in G major | 1935 | |

| Duo for Violin, Cello, and small Orchestra | 1937 | |

| Small Symphony in G major | 1939 | |

| Elegy and Roundelay | 1940 | |

| Symphony in C major | 1940 | Also known as "An die Freunde" (To the Friends). |

| Cello Concerto in A minor | 1944 | |

| Cracow Greetings | 1944 | |

| Fantasie in A minor | 1947 |

Chamber Works

Pfitzner wrote several pieces for small groups of instruments. These include:

- Piano Trio in B-flat major (1886)

- String Quartet [No 1.] in D minor (1886)

- Sonata in F-sharp minor for Cello and piano (1890)

- Piano Trio in F major (1890–96)

- String Quartet [No. 2] in D major (1902–03)

- Piano Quintet in C major (1908)

- Sonata in E minor for Violin and Piano (1918)

- String Quartet [No. 3] in C-sharp minor (1925)

- String Quartet [No. 4] in C minor (1942)

- Sextet in G minor (1945) for clarinet, violin, viola, cello, contrabass, and piano.

Instrumental Works

Pfitzner also composed pieces for solo instruments, mainly piano:

- 5 Piano Pieces (1941)

- 6 Studien for piano (1942)

Choral Works

He wrote music for choirs, sometimes with solo singers and orchestra:

- Der Blumen Rache (1888) – a ballad for women's choir.

- Columbus (1905) – for mixed choir.

- Von Deutscher Seele (1921) – for four soloists, mixed choir, orchestra, and organ.

- Das dunkle Reich (1929) – a choral fantasy.

- Urworte. Orphisch (1948-49) – a cantata completed after his death.

Songs with Piano Accompaniment

Pfitzner composed many songs for voice and piano, often setting poems by famous writers like Joseph von Eichendorff, Heinrich Heine, and Goethe. Some of these songs were also arranged for voice and orchestra.

See also

In Spanish: Hans Pfitzner para niños

In Spanish: Hans Pfitzner para niños