Leoš Janáček facts for kids

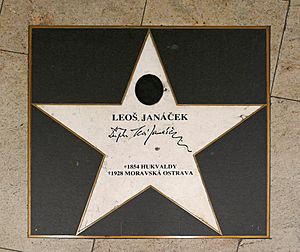

Leoš Janáček (born Leo Eugen Janáček; 3 July 1854 – 12 August 1928) was a famous Czech composer. He was also a music expert, a folklorist (someone who studies folk traditions), a writer, and a teacher. He found inspiration in the traditional music of Moravia and other Slavic countries, including Eastern European folk music. This helped him create his own unique and modern musical style.

Before 1895, Janáček spent most of his time researching folk music. At first, his music sounded a bit like other composers of his time, such as Antonín Dvořák. But later, his own style developed. He combined his studies of folk music with modern ideas. You can first hear this new style in his opera Jenůfa, which was first performed in 1904 in Brno.

When Jenůfa became a big success in Prague in 1916, Janáček's music became known around the world. His later works are his most famous. These include operas like Káťa Kabanová and The Cunning Little Vixen, the Sinfonietta, the Glagolitic Mass, and the rhapsody Taras Bulba. He also wrote two string quartets and other chamber music. Janáček is considered one of the most important Czech composers, along with Dvořák and Bedřich Smetana.

Contents

Biography

Early Life

Leoš Janáček was born in Hukvaldy, Moravia, which was part of the Austrian Empire at the time. His father, Jiří, was a schoolmaster, and his family didn't have much money. Leoš was a very talented child, especially in singing in choirs. His father wanted him to become a teacher, like him, but he saw Leoš's amazing musical skills and let him follow his passion.

In 1865, young Janáček joined the foundation of the Abbey of St. Thomas in Brno. There, he sang in choirs under Pavel Křížkovský and sometimes played the organ. One of his classmates said Janáček was an "excellent pianist." Křížkovský thought Janáček was a bit difficult but still suggested he go to the Prague Organ School. Janáček later remembered Křížkovský as a great conductor and teacher.

Janáček first planned to study piano and organ, but he later decided to focus on composing music. He wrote his first vocal pieces while leading the Svatopluk Artisan's Association choir from 1873 to 1876. In 1874, he started studying at the Prague organ school.

Life as a student in Prague was hard because he was poor. He didn't even have a piano in his room, so he practiced on a keyboard drawn on his tabletop! He once criticized a teacher's performance in a journal, which almost got him kicked out of school. But his teacher changed his mind, and Janáček graduated in 1875 with the best grades in his class.

When he returned to Brno, he became a music teacher and led several amateur choirs. From 1876, he taught music at Brno's Teachers' Institute. One of his students there was Zdenka Schulzová, who later became his wife. He also took piano lessons and performed in concerts. In 1876, he became the choirmaster of the Beseda brněnská Philharmonic Society, a role he held until 1888.

From 1879 to 1880, he studied piano, organ, and composition at the Leipzig Conservatory. He wrote a piano piece called Zdenka's Variations there. He wasn't happy with his teachers and couldn't study in Paris, so he moved to the Vienna Conservatory. He left Vienna in 1880, feeling a bit disappointed.

He returned to Brno and married Zdenka Schulzová on 13 July 1881.

In 1881, Janáček started and became the director of the organ school. He stayed in this job until 1919, when the school became the Brno Conservatory. In the mid-1880s, Janáček began composing more regularly. He wrote Four male-voice choruses (1886), which he dedicated to Antonín Dvořák, and his first opera, Šárka (1887–88). During this time, he also started collecting and studying folk music, songs, and dances.

In 1887, he strongly criticized a comic opera by another Czech composer, Karel Kovařovic. Janáček said the music and story weren't connected. This criticism led to problems later on, as Kovařovic, who was in charge of the National Theatre in Prague, refused to put on Janáček's opera Jenůfa.

From the early 1890s, Janáček was a leader in studying folk music in Moravia and Silesia. He used folk songs and dances in his orchestral and piano pieces. Many of the tunes he used were ones he had recorded himself. Most of his work in this area was published between 1899 and 1901, but he loved folklore his whole life. His composing was still influenced by the dramatic style of Smetana and Dvořák. He didn't like German music, especially Wagner, and wrote about it in the Hudební listy journal, which he started in 1884. After his second child, Vladimír, died in 1890, he tried to write an opera called Beginning of the Romance (1891) and a cantata called Amarus (1897).

Later Years and Famous Works

In the early 1900s, Janáček composed church music, including Otčenáš (Our Father, 1901) and Ave Maria (1904). In 1901, the first part of his piano music On an Overgrown Path was published and became very popular. In 1902, Janáček visited Russia twice. On his second trip, his daughter Olga became very ill. They brought her back to Brno, but she passed away in February 1903.

Janáček put his sadness about Olga's death into his new opera, Jenůfa. He dedicated the opera to her memory. Jenůfa was performed in Brno in 1904 and had some success, but Janáček wanted it to be recognized in Prague. However, the Prague opera refused to perform Jenůfa for twelve years. Feeling sad and tired, Janáček went to a spa to rest. There, he met Kamila Urválková, whose love story inspired his next opera, Osud (Destiny).

In 1905, Janáček saw a protest in Brno where a young man was killed by the police. This event inspired his piano piece, 1. X. 1905 (From The Street). This made him even more supportive of anti-German and anti-Austrian ideas. In 1906, he started working with the Czech poet Petr Bezruč, creating several choir pieces based on Bezruč's poems.

Janáček's life in the early 1900s was difficult, both personally and professionally. He still wanted to be recognized in Prague. He even destroyed some of his works, and others were never finished. But he kept composing, creating many wonderful choir, chamber, orchestral, and opera pieces. His fifth opera, Výlet pana Broučka do měsíce, composed from 1908 to 1917, is known as the most "purely Czech" of his operas.

In 1916, he began a long friendship and working relationship with the writer Max Brod. In the same year, Jenůfa was finally performed at the National Theatre in Prague. It was a huge success and brought Janáček his first big fame. He was 62 years old!

From 1917 to 1919, he composed The Diary of One Who Disappeared. As he finished it, he started his next work inspired by Kamila, the opera Káťa Kabanová.

In 1920, Janáček retired as director of the Brno Conservatory but continued teaching until 1925. In 1921, he heard a lecture by the Indian poet Rabindranath Tagore and used one of Tagore's poems for his choir piece The Wandering Madman (1922). Around the same time, he finished his opera The Cunning Little Vixen, which was inspired by a story in a newspaper.

In 1924, when Janáček was 70, a book about his life was published. In 1925, he stopped teaching but kept composing. He received the first honorary doctorate from Masaryk University in Brno. In 1926, he created his Sinfonietta, a grand orchestral piece that quickly became very popular. That same year, he visited England. Many of his works were performed in London. Soon after, he started composing a large orchestral piece called Glagolitic Mass, using an old Slavic text.

Janáček was an atheist, meaning he didn't believe in organized religion, but religious themes often appeared in his music. The Glagolitic Mass was partly inspired by a friend's suggestion and partly by Janáček's wish to celebrate the anniversary of Czechoslovakia's independence.

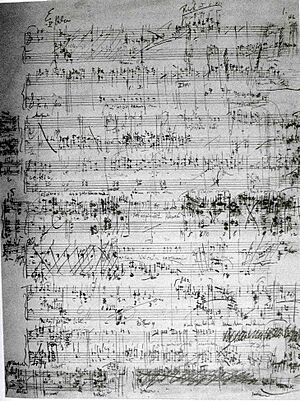

In 1927, Janáček began his last opera, From the House of the Dead. The third act of this opera was found on his desk after he died. In January 1928, he started his second string quartet, the Intimate Letters, which he called his "manifesto on love." In his later years, Janáček became famous worldwide. He joined the Prussian Academy of Arts in Berlin in 1927. His operas and other works were finally performed on major stages around the globe.

In August 1928, he went on a trip with Kamila Stösslová and her son. He caught a cold that turned into pneumonia. He passed away on 12 August 1928, in Ostrava, at the age of 74. He had a large public funeral with music from his Cunning Little Vixen. He was buried in the Field of Honour at the Central Cemetery in Brno.

Personality

Janáček worked very hard his whole life. He led the organ school, taught at the teachers' institute, collected his "speech tunes," and composed music. From a young age, he was an individualist and had strong opinions, which often led to disagreements. He openly criticized his teachers, who saw him as rebellious. However, his own students found him strict and demanding. One student described Janáček's choppy way of speaking, noting that it appeared in some of his opera characters.

His married life was calm at first, but it became more difficult after his daughter, Olga, died in 1903. Years of working without much recognition made him feel very down. He wrote later, "I was beaten down. My own students gave me advice – how to compose, how to speak through the orchestra." His success in 1916, when Jenůfa was finally performed in Prague, brought new challenges. Janáček reluctantly accepted changes made to his work.

Style

In 1874, Janáček became friends with Antonín Dvořák and started composing in a more traditional, Romantic style. After his opera Šárka (1887–1888), his music began to include elements of Moravian and Slovak folk music.

He learned to use the rhythms, ups and downs, and sounds of normal Czech speech (especially the Moravian dialect) in his music. This helped create the very unique singing style in his opera Jenůfa (1904). The success of Jenůfa in Prague in 1916 was a turning point for him. In Jenůfa, Janáček developed a special way of using "speech tunes" to create a unique musical and dramatic style. This style was very different from the popular "Wagnerian" way of composing operas. He studied how "speech tunes" changed, the feelings of the speakers, and how speech flowed. This helped him create very real and dramatic characters in his later operas, and it became a key part of his style. Janáček took these ideas even further than other composers like Modest Mussorgsky, and his work was similar to what Béla Bartók would do later. Most of Janáček's best-known works were composed in the last ten years of his life.

Much of Janáček's music is very original and unique. It uses a wider range of tonality (the way music is organized around a main note) and often uses modes (different kinds of scales). He believed that "there is no music without key." Janáček often used repeating musical patterns. The music keeps moving forward through short, "unfinished" musical ideas that repeat and build up energy. Janáček called these repeating ideas "sčasovka." It's a Czech word that means a "little flash of time" or a "musical capsule." These short, quick musical ideas with special rhythms "pepper" the music. Janáček's use of these repeated ideas is a bit like what minimalist composers do.

Inspiration

Folklore

Janáček was greatly influenced by folklore, especially Moravian folk music. But he didn't just copy it in a romantic way. He studied it very carefully and realistically. Moravian folk songs are often freer and have more unusual rhythms and melodies compared to songs from other parts of the Czech Republic. Janáček found that the folk musicians didn't have names for their musical modes (types of scales) but had their own ways of describing them. He thought their "Moravian modulation" (a way of changing keys) was a special feature of this region's folk music.

Janáček wrote original piano music for over 150 folk songs, respecting their original purpose. He also used folk ideas in his own compositions, especially his later ones. He didn't just imitate the style; instead, he created a new and original musical style based on his deep study of folk music. By carefully writing down folk songs as he heard them, Janáček became very sensitive to the melodies and rhythms of speech. He collected these special parts of spoken language, calling them "speech tunes." He used these "essences" of spoken language in his vocal and instrumental works. The unique sound of his music, with its human speech-like rhythms, comes from the world of folk music.

Russia

Janáček loved Russia and Russian culture his whole life, and this was another important source of inspiration for his music. In 1888, he saw a performance of Tchaikovsky's music in Prague and met the older composer. Janáček greatly admired Tchaikovsky, especially how he used Russian folk ideas in his music. Janáček's Russian inspiration is very clear in his later chamber music, symphonies, and operas. He followed Russian music developments from a young age. In 1896, after his first visit to Russia, he started a Russian Circle in Brno. Janáček read Russian books in their original language. Russian literature gave him many ideas, even though he knew about the problems in Russian society.

When he was 22, he wrote his first piece based on a Russian theme: a melodrama called Death, based on a poem by Lermontov. In his later works, he often used stories with clear plots. In 1910, a Russian fairy tale inspired his Fairy Tale for Cello and Piano. He composed the rhapsody Taras Bulba (1918) based on a short story by Gogol. Five years later, in 1923, he finished his first string quartet, inspired by Tolstoy's Kreutzer Sonata. Two of his later operas were also based on Russian themes: Káťa Kabanová, composed in 1921 from Alexander Ostrovsky's play The Storm, and his last work, From the House of the Dead, which was based on Dostoyevsky's novel.

Other Composers

Janáček always greatly admired Antonín Dvořák and dedicated some of his works to him. He even rearranged some of Dvořák's music. In the early 1900s, Janáček became more interested in the music of other European composers. His opera Destiny was a response to another famous work of the time, Louise, by the French composer Gustave Charpentier. The influence of Giacomo Puccini can be seen in Janáček's later works, like his opera Káťa Kabanová. Even though he paid attention to new music in Europe, his operas always stayed strongly connected to Czech and Slavic themes.

Folk Music Research

Janáček grew up in a region with strong folk culture. He started exploring it as a young student. Meeting the folklorist František Bartoš was very important for Janáček's own development as a folklorist and composer. They worked together to systematically collect folk songs. Janáček became an important collector himself, especially of songs from different parts of Moravia and Slovakia. From 1879, his collections included notes on how people spoke. He helped organize the Czech-Slavic Folklore Exhibition, a big event in Czech culture in the late 1800s. From 1905, he led a committee for Czech National Folksong in Moravia and Silesia. Janáček was also a pioneer in using ethnographic photography in Moravia and Silesia. In 1909, he bought an Edison phonograph and was one of the first to use recordings for folk music research. Some of these recordings still exist today.

Criticism

At the beginning of the 20th century, music experts in the Czech Republic were very influenced by Romantic music, especially by composers like Wagner and Smetana. People were not very open to new musical styles. During his lifetime, Janáček reluctantly agreed to changes made to his opera Jenůfa by Karel Kovařovic. Kovařovic added more trumpets and French horns to make the ending sound more "festive," saying Janáček's original music was "poor." Later, the original music for Jenůfa was restored by Charles Mackerras and is now performed as Janáček intended.

Another important Czech music expert, Zdeněk Nejedlý, who greatly admired Smetana, criticized Janáček. He called Janáček's style "unanimated" and his opera duets "only speech melodies," without strong musical layers. Nejedlý thought Janáček was more of an amateur composer whose music didn't fit Smetana's style. According to Charles Mackerras, Nejedlý tried to harm Janáček's career.

Janáček's friend and collaborator Václav Talich, a famous conductor, sometimes changed Janáček's music, mainly the instruments and how loud they played. Some critics strongly disagreed with this. Talich re-orchestrated Taras Bulba and the Suite from Cunning Little Vixen, saying it couldn't be performed in the Prague National Theatre otherwise. Talich's changes made Janáček's unique sounds and contrasts less clear, but his version was used for many years. Charles Mackerras began studying Janáček's music in the 1960s and gradually brought back the composer's original musical ideas.

Legacy

Janáček was one of the 20th-century composers who wanted music to be more realistic and connected to everyday life. His operas, in particular, use melodies that sound like spoken words, folk music, and complex musical ideas. Janáček's works are still performed regularly around the world and are very popular with audiences. He also inspired later composers and music experts in his home country.

His operas from his later years, such as Jenůfa (1904), Káťa Kabanová (1921), The Cunning Little Vixen (1924), The Makropulos Affair (1926), and From the House of the Dead (first performed after his death in 1930), are considered his best works. The Australian conductor Sir Charles Mackerras became very well known for conducting Janáček's operas.

Janáček's chamber music, though not a huge amount, includes pieces that are considered classics of the 20th century. These are especially his two string quartets: Quartet No. 1, "The Kreutzer Sonata", inspired by Tolstoy's novel, and Quartet No. 2, "Intimate Letters".

The first performance of Janáček's Concertino for piano and other instruments took place in Brno in 1926. It was also performed at a festival in Frankfurt in 1927.

Another unique chamber piece is the Capriccio for piano left hand, flute, trumpets, trombones, and tenor tuba. It was written for a pianist who lost the use of his right hand during World War I. This piece became very famous after its first performance in Prague in 1928.

Other well-known pieces by Janáček include the Sinfonietta, the Glagolitic Mass (with text in Old Church Slavonic), and the rhapsody Taras Bulba. These pieces and the five late operas mentioned above were all written in the last ten years of Janáček's life.

Janáček started a school for composers in Brno. Some of his notable students were Jan Kunc, Václav Kaprál, and Pavel Haas. Most of his students did not copy his style, so he didn't have direct followers. According to Milan Kundera, Janáček developed his own modern style somewhat separately from other modern movements, but he was still aware of new music in Europe. His journey to his unique "modernism" in his later years was long and he truly found his own voice as a composer around age 50.

Sir Charles Mackerras, the Australian conductor who helped make Janáček's operas famous around the world, said his style was "... completely new and original, different from anything else ... and impossible to pin down to any one style." Mackerras noted that Janáček's use of whole-tone scales was different from Debussy's, his folk music inspiration was unlike Dvořák's or Smetana's, and his complex rhythms were different from young Stravinsky's.

The French conductor and composer Pierre Boulez called Janáček's music surprisingly modern and fresh. He said, "Its repetitive pulse varies through changes in rhythm, tone and direction." He described Janáček's opera From the House of the Dead as "primitive, in the best sense, but also extremely strong, like the paintings of Léger."

The Czech conductor and writer Jaroslav Vogel wrote what was for a long time considered the main book about Janáček in 1958.

Janáček's life has been shown in several films. In 1983, the Brothers Quay made a stop motion animated film, Leoš Janáček: Intimate Excursions, about his life and work. In 1986, the Czech director Jaromil Jireš made Lev s bílou hřívou (Lion with the White Mane), which showed the love inspirations behind Janáček's works. In Search of Janáček is a Czech documentary from 2004, made to celebrate 150 years since his birth. An animated cartoon version of The Cunning Little Vixen was made in 2003 by the BBC. The progressive rock band Emerson, Lake & Palmer used a part of the Sinfonietta for their song "Knife-Edge" in 1970.

The Janáček Philharmonic Orchestra was created in 1954. Today, this orchestra often plays modern music but also performs classical pieces. The orchestra is based in Ostrava, Czech Republic, and tours around the world.

Asteroid 2073 Janáček, discovered in 1974, is named in his honor. The novel 1Q84 by Haruki Murakami uses Janáček's Sinfonietta as an important part of the story. Ostrava's international airport was renamed after Janáček in November 2006.

|

See also

In Spanish: Leoš Janáček para niños

In Spanish: Leoš Janáček para niños

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |