Marianne Weber facts for kids

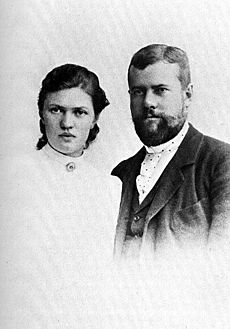

Marianne Weber (born Marianne Schnitger, August 2, 1870 – March 12, 1954) was an important German sociologist. She also worked hard for women's rights. She was married to Max Weber, a famous sociologist.

Contents

Life Story

Growing Up (1870–1893)

Marianne Schnitger was born on August 2, 1870, in Oerlinghausen, Germany. Her father, Eduard Schnitger, was a doctor. Her mother, Anna Weber, came from a well-known business family. When Marianne was only three years old, her mother passed away.

After her mother's death, Marianne moved to Lemgo. Her grandmother and aunt raised her for the next 14 years. During this time, her father and his two brothers faced serious mental health challenges. When Marianne turned 16, her grandfather, Karl Weber, sent her to special finishing schools. She finished these schools when she was 19. After her grandmother died in 1889, Marianne lived with her aunt Alwine in Oerlinghausen.

In 1891, Marianne started spending time with the Weber family in Charlottenburg. She became very close to Max Weber Jr. and his mother, Helene. Marianne admired Helene greatly. In 1893, Marianne and Max Weber got married in Oerlinghausen. They then moved into their own home in Berlin.

Married Life (1893–1920)

In the first years of their marriage, Max taught in Berlin. Then, in 1894, he taught at the University of Heidelberg. Marianne continued her own studies during this time. After moving to Freiburg in 1894, she studied with Heinrich Rickert, a leading philosopher.

Marianne also became involved in the women's movement. She heard many important feminist speakers at a meeting in 1895. In 1896, she helped start a group in Heidelberg. This group aimed to share feminist ideas. She also worked with Max to help more women attend the university.

In 1898, Max became very unwell. This happened after his father's death. Between 1898 and 1904, Max stepped back from public life. He spent time in hospitals and traveled a lot. He also resigned from his job at the University of Heidelberg. During this period, Marianne took on more public roles. She attended political meetings and published her first book in 1900. It was called Fichtes Sozialismus und sein Verhältnis zur Marxschen Doktrin. This means "Fichte's Socialism and its Relation to Marxist Doctrine."

In 1904, the Webers visited America. Marianne met Jane Addams and Florence Kelley there. Both were strong feminists and worked for political change. That same year, Max returned to public life. He published his famous book, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. Marianne also continued her own research. In 1907, she published her important work, Ehefrau und Mutter in der Rechtsentwicklung. This means "Wife and Mother in the Development of Law."

In 1907, Karl Weber, Marianne's grandfather, died. He left her enough money for the Webers to live comfortably. Around this time, Marianne started her famous intellectual salon. A salon was a regular gathering where people discussed ideas. Between 1907 and the start of World War I, Marianne became more respected as a thinker and scholar. She published several works, including "The Question of Divorce" (1909) and "On the Valuation of Housework" (1912).

World War I began in 1914. Max was busy publishing his studies on religion. He also lectured, organized hospitals, and advised on peace talks. He even ran for office in the new Weimar Republic. Marianne also published many works during this time. Some of these were "The New Woman" (1914) and "War as an Ethical Problem" (1916).

In 1918, Marianne Weber joined the German Democratic Party. Soon after, she became the first woman elected as a delegate in the parliament of Baden. In 1919, she became the chairwoman of the Bund Deutscher Frauenvereine. This was the League of German Women's Associations. She held this position until 1923. In 1920, Max's sister Lili died suddenly. Max and Marianne adopted Lili's four children. Shortly after, Max Weber became ill with pneumonia. He died suddenly on June 14, 1920. Marianne was left a widow with four children to raise.

Being a Widow (1920–1954)

After Max's unexpected death, Marianne stepped back from public life. She focused her energy on preparing ten volumes of her husband's writings for publication. In 1924, the University of Heidelberg gave her an honorary doctoral degree. This was for her work on Max's writings and for her own scholarship. Between 1923 and 1926, Weber worked on Max Weber: Ein Lebensbild. This biography of Max was published in 1926.

Also in 1926, she restarted her weekly salon. She then began a period of public speaking. She spoke to very large audiences, sometimes up to 5,000 people. During this time, she continued to raise Lili's children. She had help from a close group of friends.

Marianne Weber During the Nazi Era

Weber's career as a public speaker for women's rights ended suddenly in 1935. This was when Hitler dissolved the League of German Women's Associations. During the time of the Nazi regime, until the Allied Occupation of Germany in 1945, she continued to hold her weekly salon. People at her salon often discussed philosophy, religion, and art. They would subtly criticize the Nazi system.

Weber continued to write during this time. She published Frauen und Liebe ("Women and Love") in 1935. She also published Erfülltes Leben ("The Fulfilled Life") in 1942.

Later Years

On March 12, 1954, Marianne Weber passed away in Heidelberg, in what was then West Germany.

Her Work

Main Ideas

Marianne Weber's ideas about society often focused on the experiences of women. She lived in a time when society was mostly run by men. She wrote about German women of her time. Many of these women were starting to work outside the home for the first time. This new experience changed how power worked within families.

Weber believed that laws, religion, history, and the economy were mostly created by men. These systems shaped women's lives and limited their freedom. She also felt that marriage could be studied to understand society better. Marriage was central to women's lives. It showed how law, religion, history, and the economy affected them. She noted that while marriage could limit women, it also offered them some protection. It could reduce "the brutal power of men by contract." Weber's work, especially her 1907 book Wife and Mother in the Development of Law, looked closely at marriage. She concluded that marriage was a "complex and ongoing negotiation over power and closeness."

Another important idea in her work was about women's contributions. She believed that women's work helped to "map and explain the creation of people and the social world." Human work creates cultural things. These range from small daily values like cleanliness to big ideas like philosophy. Between these two extremes is a large area called "the middle ground of immediate daily life." Women play a big part here. They are often the caretakers, child-raisers, and daily money managers of the family. Weber argued that this middle ground is where people mostly develop who they are. These developed selves then affect others in their daily actions.

She also felt that the constant struggle between our spiritual side and our animal side makes us human. This conflict is not a problem to be solved. Instead, it forms the basis of human dignity. This "long struggle of human beings to control their instincts with their free moral will" is a cultural product. Women are largely responsible for creating this.

Finally, Weber also believed that differences like social class, education, age, and beliefs greatly affected women's daily lives. She saw big differences not just between women in the countryside and cities. There were also differences among different types of rural women and urban women. Urban women, like Weber herself, were defined not just by their husbands' jobs but also by their own. Among working women, their jobs (like traditional women's work versus academics or artists) affected their daily lives. This led to different needs, lifestyles, and overall beliefs.

Georg Simmel and Marianne Weber

Many people have discussed the connection between Max Weber and Georg Simmel. But Marianne Weber was also a colleague of Simmel. They were friends for over 20 years. During this time, Max and Simmel often talked and wrote letters. Marianne Weber also wrote a response to Simmel's 1911 essay. In it, she criticized his ideas about "gender relations." Both sociologists studied "the woman question." They also looked at how gender shapes individuals and society.

See also

In Spanish: Marianne Weber para niños

In Spanish: Marianne Weber para niños

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |