Heidelberg Castle facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Heidelberg Castle |

|

|---|---|

|

Heidelberger Schloss

|

|

|

|

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Gothic & Renaissance |

| Town or city | Heidelberg |

| Country | Germany |

| Construction started | before 1214 |

| Owner | Bishop of Worms (first known owner) State of Baden-Württemberg |

Heidelberg Castle (German: Heidelberger Schloss) is a famous ruin in Germany. It is a well-known landmark in the city of Heidelberg. The castle ruins are considered some of the most important Renaissance buildings north of the Alps.

The castle was mostly destroyed in the 1600s and 1700s. It has only been partly rebuilt since then. It sits about 80 meters (262 feet) up the northern side of the Königstuhl hill. From this spot, it offers amazing views of the old downtown area. You can reach the castle by taking a funicular railway from Heidelberg's Kornmarkt.

The first castle building was constructed before 1214. It was later made bigger into two castles around 1294. However, in 1537, a lightning bolt struck and destroyed the upper castle. The buildings you see today were expanded by 1650. After that, wars and fires caused more damage. In 1764, another lightning bolt caused a fire that ruined some rebuilt parts. By 1880, the famous writer Mark Twain described it as a ruin.

Contents

History of Heidelberg Castle

Early Beginnings

Heidelberg was first mentioned in 1196. In 1155, Conrad of Hohenstaufen became the Count Palatine. This meant he was a powerful ruler in the region, which became known as the Electoral Palatinate. The first time a castle in Heidelberg was mentioned was in 1214. This was when Louis I, Duke of Bavaria received it from Emperor Friedrich II.

By 1303, documents started mentioning two castles:

- The upper castle on Kleiner Gaisberg Mountain (destroyed in 1537).

- The lower castle on the Jettenbühl, which is where the current castle stands.

The lower castle was built sometime between 1294 and 1303. Under Ruprecht I, a church was built at the castle.

A Royal Residence

When Ruprecht became King of Germany in 1401, the castle was too small for his large group of people. He wanted more space and stronger defenses.

After Ruprecht passed away in 1410, his land was divided among his four sons. His eldest son, Ludwig III, received the Palatinate. Ludwig was an important judge. In 1415, he held Antipope John XXIII captive at the castle.

The French writer Victor Hugo visited Heidelberg in 1838. He enjoyed walking among the castle ruins. He wrote about its long history and how it faced many challenges over five hundred years. He noted that the castle was often in conflict with powerful rulers like kings and emperors.

-

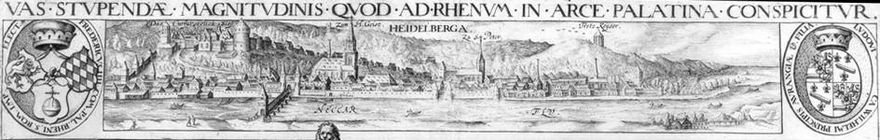

The castle and town, by Matthäus Merian.

-

A Romantic painting of the castle by J. M. W. Turner.

Wars and Destruction

During the rule of Louis V, Elector Palatine (1508–1544), Martin Luther visited Heidelberg. He came to discuss his ideas and saw the castle. He wrote to a friend, praising the castle's beauty and strong defenses.

In 1619, Frederick V, Elector Palatine accepted the crown of Bohemia. This decision helped start the Thirty Years War. For the first time, the castle faced attacks. This period marked the end of new construction. The years that followed brought destruction and rebuilding.

After Frederick V's defeat in 1620, his lands were left open to attack. On August 26, 1622, General Tilly attacked Heidelberg. He took the town in September and the castle a few days later.

In 1633, the Swedes captured Heidelberg. They fired on the castle from the Königstuhl hill. The castle's commander surrendered. The emperor's troops recaptured it in 1635. It remained theirs until the Peace of Westphalia ended the Thirty Years War. The new ruler, Charles Louis, moved into the ruined castle in 1649.

Victor Hugo also wrote about these events. He noted how many powerful figures, including emperors and kings, had attacked or influenced the castle.

The Nine Years' War

After Charles II, Elector Palatine passed away, Louis XIV of France claimed the Palatinate. This led to the War of the Grand Alliance, also known as the Nine Years' War. On September 29, 1688, French troops marched into the Palatinate. On October 24, they entered Heidelberg.

France decided to destroy all forts and lay waste to the Palatinate. This was to stop enemy attacks. As the French left the castle on March 2, 1689, they set it on fire. They also blew up part of the Fat Tower. Some parts of the town were burned too. However, a French general, René de Froulay de Tessé, told the townspeople to make small fires. This created smoke and made it look like the whole town was burning, preventing more damage.

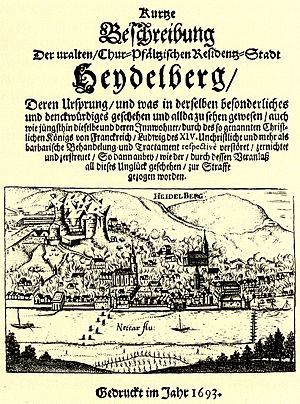

In 1690, Johann Wilhelm, Elector Palatine began rebuilding the walls and towers. When the French returned in 1691 and 1692, the town's defenses were strong. But on May 18, 1693, the French took the town again. They could not take the castle, so they destroyed the town to weaken the castle's support. The castle's defenders surrendered the next day. The French then finished destroying the towers and walls that had survived the first attack.

Moving the Court to Mannheim

In 1697, the Treaty of Ryswick brought peace. There were plans to take down the castle and use its parts for a new palace. But this was difficult, so the castle was just repaired. Charles III Philip, Elector Palatine thought about redesigning the castle. However, he did not have enough money. He did, however, hire Perkeo of Heidelberg, his favorite jester, to look after the castle's wine. Perkeo became a mascot for the city.

In 1720, Charles had a disagreement with the Protestants in the town. He gave the Church of the Holy Spirit entirely to the Catholics. Because of this, the Catholic prince-elector moved his court to Mannheim. He lost all interest in the castle. He even said he wished "Grass may grow on her streets."

Moving to Mannheim also made sense because turning the old castle into a modern Baroque palace would have been very expensive. In Mannheim, the prince-elector could build a new palace, Mannheim Palace, exactly as he wanted.

Karl Theodor, Charles Philip's successor, planned to move his court back to Heidelberg Castle. But on June 24, 1764, lightning struck the court building twice. This set the castle on fire again. Karl Theodor saw this as a sign from heaven and changed his plans. Victor Hugo also saw it as a divine sign. He wrote that if Karl Theodor had moved in, the castle would have been decorated in a fancy style, losing its charm as a ruin.

For many years after, only basic repairs were done. Heidelberg Castle remained mostly a ruin.

The Castle as a Ruin

Slow Decay and Romantic Views

In 1777, Karl Theodor became ruler of Bavaria and moved his court to Munich. Heidelberg Castle became even less important to him. Craftsmen used the rooms that still had roofs. As early as 1767, stones from the south wall were used to build Schwetzingen Castle. By 1784, the castle was used as a source of building materials for local houses.

In 1803, Heidelberg became part of Baden. The Grand Duke of Baden saw the castle as an unwanted old ruin. Local people took stones, wood, and iron from the castle for their own homes. Statues and decorations were also taken.

Around 1800, artists began to see the castle ruins, river, and hills as a beautiful scene. J. M. W. Turner, an English painter, visited Heidelberg many times between 1817 and 1844. He painted the castle often. He and other Romantic painters were more interested in creating artistic images than exact copies. For example, Turner's paintings show the castle much higher on the hill than it really is.

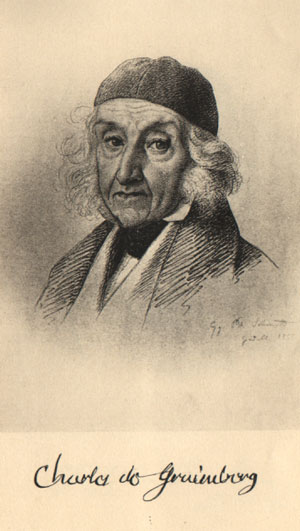

The French count Charles de Graimberg helped save the castle. He fought against the government of Baden, which wanted to tear down the ruins. Until 1822, he worked as a volunteer castle warden. He lived in one of the castle wings to watch over the courtyard. He was one of the first people to care about saving and documenting the castle. Graimberg also asked Thomas A. Leger to write the first guide to the castle. His pictures of the castle helped make it famous and brought many tourists to Heidelberg.

Planning for the Future

For a long time, people debated whether the castle should be fully restored. In 1868, a poet suggested rebuilding it completely. This caused a big discussion.

In 1883, the Grand Duchy of Baden created a "Castle field office." Experts studied the castle and decided that a full rebuilding was not possible. However, they agreed it could be preserved as it was. Only the Friedrich Building, which was damaged by fire but not completely ruined, would be restored. This restoration happened from 1897 to 1900 and cost a lot of money.

Castle Ruins and Tourism

Heidelberg was mentioned as a city "frequented by strangers" in 1465. But it only became a major tourist spot in the early 1800s. Count Graimberg's pictures of the castle became popular, like early postcards. The castle also appeared on souvenir cups. Tourism grew even more when Heidelberg got a railway connection in 1840.

Mark Twain, an American author, wrote about Heidelberg Castle in his 1880 book A Tramp Abroad. He described how perfectly placed the ruin was, surrounded by green woods and terraces. He noted how nature had decorated the split towers with flowers and plants, making them beautiful. He felt that misfortune had actually improved the old tower, just as it sometimes improves human character.

In the 1900s, Americans helped spread Heidelberg's fame outside Europe. Today, many Japanese tourists also visit Heidelberg Castle. In the early 2000s, Heidelberg had over three million visitors a year. The castle and its viewing terraces are the most popular attractions.

Timeline of Events

- 1225: First official mention as "Castrum" (castle).

- 1303: Two castles are mentioned.

- 1537: The upper castle is destroyed by lightning.

- 1610: The beautiful palace garden (Hortus Palatinus) is created.

- 1622: Tilly's army captures the city and castle during the Thirty Years War.

- 1642: The castle grounds are renewed.

- 1688/1689: French troops destroy parts of the castle.

- 1693: The castle is destroyed again in the Palatinate succession war.

- 1697: Reconstruction begins.

- 1720: The royal court moves to Mannheim.

- 1742: Reconstruction begins again.

- 1764: Lightning strikes and destroys more of the castle.

- 1810: Charles de Graimberg starts working to preserve the castle ruins.

- 1860: The first time the castle is lit up at night.

- 1883: The "office of building of castles of Baden" is created.

- 1890: Experts Julius Koch and Fritz Seitz complete a detailed study of the castle.

- 1900: Restorations and historical developments are completed.

Famous People Connected to the Castle

Frederick V: The "Winter King"

Frederick V, Elector Palatine married Elizabeth Stuart, the daughter of the English king. Their wedding involved huge celebrations and costs. He even had the Elizabeth gate built for the festivities.

Frederick V spent time in England and met important architects. These architects later helped with changes and new plans for Heidelberg Castle. They started building a huge garden, which was a big challenge because it was on a mountain slope. People at the time called it the "eighth wonder of the world."

Under Frederick V, the Palatinate tried to become the most powerful Protestant state. However, this ended badly. In 1619, Frederick V was chosen as the Bohemian king. But he lost the Battle of White Mountain against the Emperor's troops. He was called the "Winter King" because his rule lasted only a little longer than one winter. After this, Frederick V became a political refugee.

When Frederick V left Heidelberg, his mother reportedly said, "Oh, the Palatine is moving to Bohemia." After Frederick escaped to the Netherlands, Emperor Ferdinand II banned him in 1621. The Rhein Palatinate was given to Duke Maximilian I of Bavaria in 1623. Frederick V lived in exile, hoping to regain his position, but he passed away in 1632.

Elizabeth Charlotte, Princess Palatine

Elizabeth Charlotte, Princess Palatine was a duchess and the sister-in-law of Louis XIV of France. When her family line ended, Louis XIV claimed the Palatinate. This led to the War of the Grand Alliance, which destroyed the Palatinate. Liselotte, as she was known, had to watch helplessly as her homeland was ruined.

Liselotte, Frederick V's granddaughter, was born at Heidelberg Castle. She grew up at her aunt's court in Hanover. She often returned to Heidelberg with her father. At 19, she married the French king's brother for political reasons. It was not a happy marriage. When her brother Charles died without children, Louis XIV claimed the Palatinate and declared war.

Liselotte wrote in a letter that her father probably did not understand how big a deal it was to marry her off. She felt he just wanted to get rid of her quickly. Even after 36 years in France, she still thought of Heidelberg as home. She wrote, "Why does the prince elector not have the castle rebuilt? It would certainly be worth it."

Liselotte's children later became part of the French royal family. Liselotte wrote an estimated 60,000 letters, and about a tenth of them still exist. These letters, written in French and German, describe life at the French court very well. She wrote to her aunt and half-sister, and also to Gottfried Leibniz.

Liselotte had a simple upbringing. Charles I Louis, Elector Palatine loved to play with his children in Heidelberg and walk in the hills. Liselotte described herself as a "lunatic bee." She rode her horse fast over the hills and enjoyed her freedom. She often snuck out of the castle early to climb a cherry tree and eat cherries. In 1717, she remembered her childhood: "My God, how often at five in the morning I stuffed myself with cherries and a good piece of bread on the hill! In those days I was lustier than now I am."

Charles de Graimberg

The French engraver Count Charles de Graimberg fled the French Revolution. He came to Heidelberg in 1810 to sketch the castle. He ended up staying for the rest of his life, 54 years. His engravings of the castle ruins showed its condition and helped start the movement to protect it from further decay.

In his house, which is now called Palace Graimberg, he created a collection of items found at the castle. This collection later became the start of the Kurpfälzisches Museum. He used his own money to pay for his collection of old items related to the city and castle's history. It is thanks to him that the castle still stands. He also did the first historical digs at the castle. He even lived in the castle courtyard for a while to stop people from taking building materials from the ruins for their own homes.

Graimberg asked Thomas A. Leger to write the first castle guide. Victor Hugo bought a copy of this guide in 1836 during his visit to Heidelberg. This copy, with Hugo's notes, is now in the Maison de Victor Hugo in Paris.

A plaque honors Charles de Graimberg at the castle. It reads: "To the memory of Karl count von Graimberg, born in Castle of Paars (near Château-Thierry) in France 1774, died in Heidelberg 1864."

Castle Buildings

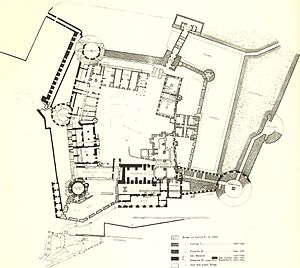

The Forecourt

The forecourt is the area between the main gate, the upper prince's well, the Elisabeth gate, the castle gate, and the garden entrance. Around 1800, the overseer used it for drying laundry. Later, it was used for grazing cattle, and chickens and geese were kept there.

Main Building Parts

Ruprechtsbau, Ruprecht's Wing

Bibliotheksbau, Library Building

Frauenzimmerbau, Ladies' Wing

Englischer Bau, English Wing

Friedrichsbau, Friedrich's Wing

The building where the Friedrichsbau now stands used to have the court chapel. Because of serious damage, Elector Friedrich IV had a new residential building built between 1601 and 1607. Johannes Schoch was the architect. The outside of the building was decorated with statues of the electors' ancestors. Sebastian Götz was the main sculptor.

Friedrich's wing has the court chapel on the ground floor. The prince's apartment is on the upper floors.

Even though there were two big fires in 1693 and 1764, this is the best-preserved part of the castle. From 1890 to 1900, the Friedrichsbau was fully renovated. The current roof and the rooms on the second and third floors are from this renovation.

Gläserner Saalbau, Hall of Glass

Ottheinrichsbau, Ottheinrich's Wing

Torturm, Gate Tower

To reach the forecourt, you cross a stone bridge over a partly filled-in ditch. The main gate was built in 1528. The original guardhouse was destroyed in the War of the Grand Alliance. It was replaced in 1718 by a new arched entrance gate. The gate to the left of the main entrance used to have a drawbridge.

Other Interesting Spots

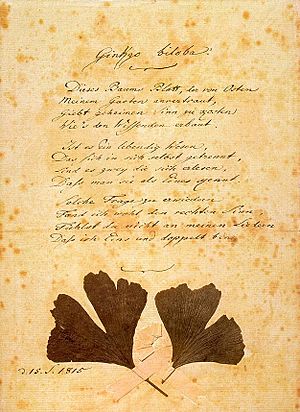

Goethe Memorial Tablet

In 1961, a stone tablet was put up on a ruined wall. It replaced an older one. The tablet has verses by Marianne von Willemer. These verses remember her last meeting with Johann Wolfgang Goethe in 1815. She wrote them on August 28, 1824, for Goethe's 75th birthday.

The poem says: "On the terrace a high vaulted arch was once your coming and going the code pulled from the beloved hand I found her not, she is no longer to be seen" ... This poem written by Marianne von Willemer in remembrance of her last meeting with Goethe in the Fall of the year 1815

Right across from the tablet is a Ginkgo tree. Goethe gave a leaf from this type of tree to Marianne von Willemer as a symbol of friendship. The poem was later published as "Suleika" in his book West-östlicher Diwan.

The poem begins:

Ginkgo Biloba

This leaf from a tree in the East,

Has been given to my garden.

It reveals a certain secret,

Which pleases me and thoughtful people.

...

The letter with this poem and two Ginkgo leaves can be seen in the Goethe Museum in Düsseldorf. The specific Ginkgo tree that inspired Goethe in 1815 is no longer standing today. However, since 1928, a Ginkgo tree in the castle garden has been marked as "the same tree that inspired Goethe to create his fine poem."

Harness Room

The old harness room was originally a coach house. It was first built as a strong defense. After the Thirty Years War, it was used as stables, a toolshed, and a place for carriages.

Upper Prince's Fountain

The Upper Prince's Fountain was built during the rule of Prince Karl Philipp. Above the gate to the fountain house, you can see his initials and the date 1738 carved in stone. On the right side of the stairs, there is an inscription.

This inscription was a special code for the date 1741. This fountain and the Lower Prince's Fountain supplied water to the Prince's homes in Mannheim until the 1800s.

In 1798, Johann Andreas von Traitteur wrote about this water transport. He said that because Mannheim did not have good, healthy water, water was brought daily from Heidelberg's mountain. There was a special water wagon that drove to Heidelberg every day to bring water from the Prince's Fountains to the castle.

The water quality in Mannheim was so poor that wealthy families paid for water to be brought from Heidelberg. Until 1777, there was even a special job at the court called "Heidelberg Water-filler."

Gallery

See also

- Hortus Palatinus, the Heidelberg Castle gardens

- Garden à la française

- Heidelberg Tun