Holocaust survivors facts for kids

Holocaust survivors are people who lived through the terrible events of the Holocaust. This was a time when Nazi Germany and its allies tried to wipe out all Jews in Europe and North Africa, before and during World War II.

There isn't one single way to define a "Holocaust survivor." It can mean Jews who survived the war in places controlled by Nazis or their allies. It also includes those who escaped to safe countries before or during the war. Sometimes, non-Jewish people who were also badly treated by the Nazis are called Holocaust survivors too.

Survivors include people found alive in Nazi concentration camps when the war ended. It also includes those who fought back as Jewish partisans, or who were hidden by brave non-Jews called the Righteous Among the Nations. Many also escaped to places where the Nazis had no control before the "Final Solution" (the Nazi plan to kill all Jews) began.

After the war, survivors faced huge challenges. They needed to heal physically and emotionally from starvation and abuse. They searched for family members and tried to reunite. Many could not go back home because their communities were destroyed or because of new hatred against Jews. So, they often moved to new, safer places.

Later, other needs came up. These included getting social and psychological help, and asking for money or property back that was stolen. They also wanted to collect their stories, remember family members who died, and care for older or disabled survivors.

Contents

Who is a Holocaust Survivor?

The term "Holocaust survivor" mainly refers to Jews who lived through the mass killings by the Nazis. But it can also include those who were greatly affected by the Nazis, even if they weren't directly under Nazi control. This includes Jews who fled Germany or their home countries to escape the Nazis. It also covers those persecuted by Nazi allies or helpers.

Yad Vashem, Israel's official memorial to Holocaust victims, says a survivor is any Jew who lived under Nazi control (direct or indirect) for any time and survived. This includes Jews who lived under Nazi-friendly governments, like France or Bulgaria, but were not sent away to camps. It also includes Jews who fled Germany in the 1930s or those who escaped to the Soviet Union to avoid the German army.

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum has a wider definition. They honor anyone, Jewish or not, who was displaced, persecuted, or discriminated against by the Nazis and their helpers between 1933 and 1945. This includes people from Nazi concentration camps, Nazi ghettos, and prisons. It also includes refugees or people who lived in hiding.

Over time, more groups have been recognized as survivors. For example, Roma (Gypsy) people who were persecuted by Nazis. Also, "flight survivors" are those who fled east into Soviet areas or were sent to different parts of the Soviet Union.

Because of this growing understanding, organizations like the Claims Conference and Yad Vashem now include these groups in their definition of survivors. This means more people can get help and be recognized, including those who lived in hiding, like children who were hidden.

How Many People Survived?

In September 1939, when World War II started, about 9.5 million Jews lived in Europe. These were countries already controlled by Nazi Germany or soon to be invaded. Sadly, almost two-thirds of these Jews, about 6 million people, were killed. By May 1945, when the war ended in Europe, about 3.5 million Jews had survived. As of January 2024, around 245,000 survivors are still alive.

Here's how some people managed to survive:

Camp Prisoners

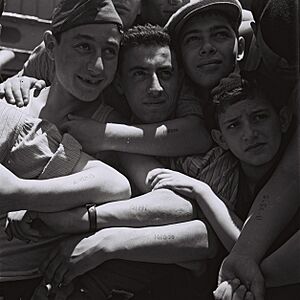

Between 250,000 and 300,000 Jews survived the concentration camps and death marches. However, tens of thousands were so sick or weak that they died within a few months after being freed, even with medical care.

Other Survivors

Many Jews in Europe survived because the Germans and their helpers could not finish their killings before the Allied forces arrived. For example, in Western Europe, about three-quarters of the Jews in France and Italy survived. About half survived in Belgium. But only a quarter survived in the Netherlands.

In Eastern and Southeastern Europe, most Jews in Bulgaria survived. About 60% survived in Romania, and nearly 30% in Hungary. Two-thirds survived in the Soviet Union. Sadly, Bohemia, Slovakia, and Yugoslavia lost about 80% of their Jewish populations. In Poland, the Baltic states, and Greece, nearly 90% of Jews were murdered.

Thousands of Jews also survived by hiding or by pretending to be non-Jews with false papers. Brave non-Jews risked their lives to help them. Several thousand Jews also hid in thick forests in Eastern Europe. Some became Jewish partisans, actively fighting the Nazis and protecting other escapees.

Refugees

The largest group of survivors were Jews who escaped from German-controlled Europe before or during the war. Jews started leaving Germany in 1933 when the Nazis came to power. By the time the war began, about 282,000 Jews had left Germany, and 117,000 had left Austria.

Only 10% of Polish Jews survived the war. Most of these survivors (around 300,000) fled to Soviet-controlled Poland and deeper into the Soviet Union between 1939 and 1941. Soviet authorities sent many to remote places like Soviet Central Asia or Siberia. Life was hard, with forced labor, hunger, and disease, but most managed to survive.

After Germany invaded the Soviet Union, over a million Soviet Jews fled eastward. During the war, some European Jews escaped to neutral European countries like Switzerland, Spain, Portugal, and Sweden. For example, in October 1943, almost all Danish Jews (7,000 Jews and 700 non-Jewish relatives) were rescued by the Danish resistance and escaped to Sweden by boat. About 18,000 Jews also secretly immigrated to Palestine between 1937 and 1944. These journeys were dangerous, and hundreds of lives were lost at sea.

Right After the War

When World War II ended, Jews who survived the Nazi concentration camps, extermination camps, and death marches were suffering greatly. They were starving, exhausted, and had been abused. Tens of thousands continued to die from weakness, disease, or the shock of being freed. Some survivors returned home, while others tried to leave Europe for Palestine or other countries.

The Trauma of Being Freed

For survivors, the end of the war did not end their suffering. Being freed was often very difficult. The change from terror and starvation to freedom was traumatic.

As Allied forces moved across Europe, they found the Nazi camps. Sometimes, Nazis tried to destroy evidence of their crimes. Other times, they had moved prisoners on death marches. But in many camps, Allied soldiers found thousands of weak and starving survivors. Soviet forces found camps like Majdanek concentration camp in 1944, but didn't always share what they found. British and American troops reached camps in Germany in spring 1945.

When Allied troops entered the death camps, they found thousands of Jewish and non-Jewish survivors. They were starving, sick, and living in terrible conditions. Many were dying. The soldiers were shocked but did their best to help. Still, thousands died in the first weeks after being freed. Many died from disease. Survivors had no belongings and often still wore their camp uniforms.

In the first weeks, survivors struggled to eat proper food, recover from illnesses, and regain a sense of normal life. Almost every survivor had lost many loved ones, often their entire family. They also lost their homes, jobs, and old ways of life.

Survivors faced the huge task of rebuilding their lives and finding any remaining family. Most also needed to find new places to live. Going back to life before the Holocaust was impossible. Many tried to return to their old homes, but Jewish communities were destroyed in much of Europe. Returning home was often dangerous. Their homes had been stolen or taken over by others. Most found no surviving relatives and faced indifference or even violence, especially in Eastern Europe.

Refugees and Displaced Persons

Jewish survivors who could not or did not want to return home became known as "Sh'erit ha-Pletah" ((Hebrew)). This group mainly came from Central and Eastern Europe. Most Western European Jews returned home and rebuilt their lives there.

Most of these refugees gathered in displaced persons camps in the British, French, and American zones of Germany, Austria, and Italy. Conditions were harsh at first. But once basic needs were met, the refugees organized themselves. They formed groups to ask for help, run cultural activities, and push for permission to leave Europe and move to British Mandate of Palestine or other countries.

The first meeting of survivors in DP camps was on May 27, 1945. They formed "Sh'erit ha-Pletah" to speak for them to the Allied authorities. This organization helped until most survivors had moved to other countries or settled down. The term "Sh'erit ha-Pletah" usually refers to Jewish refugees from 1945 to about 1950.

Displaced Persons Camps

After the war, most non-Jews who had been displaced by the Nazis went back home. But tens of thousands of Jews had no homes, families, or communities left. Many wanted to leave Europe entirely to escape antisemitism and rebuild their lives. Other Jews who tried to return home found their property stolen or faced hostility and violence.

With nowhere else to go, about 50,000 homeless Holocaust survivors gathered in Displaced Persons (DP) camps in Germany, Austria, and Italy. Moving to Mandatory Palestine was limited by the British, and other countries like the United States also had strict rules. Later, Jewish refugees fleeing worsening conditions in Eastern Europe joined them. By 1946, about 250,000 Jewish displaced persons lived in hundreds of refugee centers and DP camps. These were managed by the United States, Great Britain, France, and the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA).

Survivors faced terrible conditions in the DP camps at first. Facilities were poor, and many suffered from severe physical and mental problems. Aid was slow to arrive. Survivors were often in the same camps as German prisoners and Nazi helpers, which led to anti-Jewish violence. After a report by President Roosevelt's representative, Earl G. Harrison, U.S. authorities set up separate DP camps for Jewish survivors and improved conditions. The British were slower to act, fearing it would encourage Jews to go to Palestine and anger Arabs. So, most Jewish refugees went to the American zone.

DP camps were meant to be temporary places for refugees to resettle and get immediate help. But they also became temporary communities where survivors started new lives. With help from Jewish relief groups, hospitals and schools opened, especially for the many children and orphans. Survivors restarted cultural and religious activities. Many prepared to leave Europe. They formed committees to represent their needs, under the name Sh'erit ha-Pletah. The Zionist movement became very important, and most Jewish DPs wanted to move to a Jewish state in Palestine.

The slow handling of Jewish DPs and the growing number of people in the camps gained international attention. Public pressure grew to allow more immigration to the U.S., Canada, and Australia. There was also pressure on Britain to stop holding refugees trying to reach Palestine in internment camps on Cyprus. Britain's treatment of Jewish refugees, like the ship Exodus, shocked the world. This led to international demands for an independent Jewish state. In 1947, the United Nations voted to create a Jewish and an Arab state. When the British Mandate in Palestine ended in May 1948, the State of Israel was established. Jewish refugee ships were immediately allowed to enter without limits. The U.S. also changed its immigration policy to let more Jewish refugees in.

Most DP camps closed by 1952. Föhrenwald, the last one, closed in 1957. About 136,000 DP camp residents, more than half, moved to Israel. About 80,000 went to the United States, and others went to Canada, Australia, and other countries.

Searching for Family

As soon as the war ended, survivors began looking for family members. This was their main goal after finding food, clothing, and shelter.

Local Jewish groups in Europe tried to list who was alive and who had died. Parents searched for children they had hidden in convents, orphanages, or with foster families. Other survivors went back to their old homes to look for relatives or news. The International Red Cross and Jewish relief groups set up tracing services. But finding people was hard because communication was difficult, and millions had been moved or killed.

Organizations like the World Jewish Congress and the Jewish Agency for Palestine set up tracing services. This helped reunite survivors, sometimes decades after they were separated. For example, the American Jewish Congress helped find 85,000 survivors and reunited 50,000 relatives. However, searching for family often took years, and many survivors never learned what happened to their loved ones.

In Israel, where many Holocaust survivors moved, some relatives met by chance. Many also found family through newspaper notices for missing relatives or a radio show called Who Recognizes, Who Knows?

Lists of Survivors

At first, survivors wrote notes and put them on message boards in relief centers or DP camps. They hoped family or friends would see them, or that other survivors would share information. Others put notices in camp newsletters or newspapers. Some contacted the Red Cross and other groups that made lists of survivors. The United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration set up a Central Tracing Bureau to help survivors find relatives.

These lists were put into larger books. One early book, "Sharit Ha-Platah" (Surviving Remnant), was published in 1946. It had names of tens of thousands of Jewish survivors. It was collected mainly by Abraham Klausner, a U.S. Army chaplain who visited many DP camps.

The first "Register of Jewish Survivors" was published by the Jewish Agency in 1945. It had over 61,000 names from 166 lists. A second volume with 58,000 names of Jews in Poland was also published in 1945.

Newspapers outside Europe also started publishing lists of survivors. For example, the German-Jewish newspaper "Aufbau" in New York City printed many lists from 1944 to 1946.

Over time, many Holocaust survivor registries were created. At first, these were paper records. But since the 1990s, more records have been put online.

Hidden Children

After the war, Jewish parents spent months or years searching for the children they had sent into hiding. Luckily, some found their children still with the original rescuers. But many had to use newspapers, tracing services, and survivor registries. These searches often ended in heartbreak, as parents found their child had been killed or was missing. Thousands of hidden children were orphans, with no surviving family to find them.

For very young hidden children, more was at stake than just finding relatives. They often didn't remember their biological parents or their Jewish background. The only family they knew was their rescuers. When relatives or Jewish groups found them, they were usually scared and didn't want to leave the only caregivers they remembered. Many struggled to find their true identities.

Sometimes, rescuers refused to give up hidden children, especially orphans or those who had been baptized and raised in Christian homes. Jewish organizations and relatives had to fight to get these children back, even in court. For example, the Finaly Affair ended in 1953 when two orphaned brothers were finally given to their aunt after a long struggle.

Today, DNA testing sometimes helps people find relatives separated during the Holocaust. It also helps people find their Jewish identity, especially hidden children who were adopted by non-Jewish families.

Moving and Settling

After the war, anti-Jewish violence happened in several Central and Eastern European countries. This was partly due to economic problems and fear that returning survivors would reclaim stolen property. Old antisemitic myths, like the blood libel, also played a role. The largest anti-Jewish riot happened in July 1946 in Kielce, Poland, where 41 people were killed. As news spread, Jews began to flee Poland, feeling they had no future there. Similar violence happened in Hungary, Romania, Slovakia, and Ukraine. Most survivors wanted to leave Europe and start new lives elsewhere.

About 50,000 survivors gathered in Displaced Persons (DP) camps in Germany, Austria, and Italy. They were joined by Jewish refugees fleeing Eastern Europe. By 1946, there were about 250,000 Jewish displaced persons. As the British Mandate in Palestine ended in May 1948 and the State of Israel was established, nearly two-thirds of the survivors moved there. Others went to Western countries as immigration rules became easier.

Healing and Support

Psychological Care

Holocaust survivors suffered in many ways, physically, mentally, and emotionally.

Most survivors were deeply traumatized. Some effects lasted their whole lives. They often felt like they were on a "different planet" and couldn't share their experiences. They couldn't properly mourn their murdered loved ones because they were focused on surviving. Many felt guilty for surviving when others didn't. This terrible time left many with physical and mental scars, sometimes called "concentration camp syndrome" or survivor syndrome.

However, many survivors found inner strength. They learned to cope, rebuilt their lives, moved to new places, started families, and had successful careers.

Memories and Stories

After the war, many Holocaust survivors worked to record their experiences and remember lost family and destroyed communities. This included writing personal accounts and memoirs. They also helped create remembrance books for destroyed communities, called Yizkor books.

Survivors and witnesses also gave oral testimonies. At first, this was mainly to help catch war criminals. Later, it was to help them deal with their trauma or for history and education.

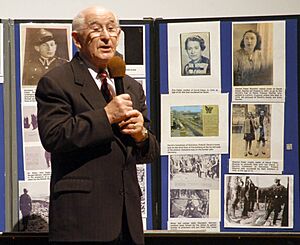

Organizations like the USC Shoah Foundation Institute started programs to collect as many oral history testimonies as possible. Survivors also began speaking at schools and public events. They helped build museums and memorials to remember the Holocaust.

Memoirs

Some survivors published memoirs right after the war. They felt a need to write about their experiences. About a dozen memoirs were published each year in the first 20 years after the Holocaust. But the public wasn't very interested then. Many survivors felt they couldn't describe their experiences to those who hadn't lived through it. Those who did write often wrote in Yiddish.

More memoirs were published from the 1970s onwards. This showed that survivors felt more able to share their stories. Public interest in the Holocaust also grew because of events like the trial of Adolf Eichmann in 1961, the threats to Jews during the Six-Day War (1967) and Yom Kippur War (1973), and the TV series "Holocaust" in 1978. New Holocaust memorials, like the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, also helped.

Writing memoirs helped survivors deal with and recover from their traumatic past. By the end of the 20th century, Holocaust memoirs were written in many languages, not just Yiddish, including Hebrew, English, and French. They were written by camp survivors, those who hid, and those who fled. Some even described life after the Holocaust, including being freed and rebuilding lives.

Survivor memoirs, like oral testimonies and diaries, are very important for historians. They add to traditional historical sources by showing events from the unique view of individual experiences. While memories can be subjective, these accounts have a "firm core of shared memory." Small differences in details don't change the main truth of their stories.

Yizkor Books

Yizkor books (Remembrance books) were created by groups of survivors or former residents of a town to remember lost family and destroyed communities. These were some of the first ways the Holocaust was remembered as a group. The first books appeared in the 1940s and were usually published privately. Over 1,000 such books are thought to have been published, but in small numbers.

Most of these books are in Yiddish or Hebrew. Some also have sections in English or other languages. The first Yizkor books were published in the United States, mostly in Yiddish. From the 1950s, after many survivors moved to Israel, most Yizkor books were published there. The number of collective memorial books decreased from the late 1970s, but personal memoirs increased. Most Yizkor books focused on Jewish communities in Eastern Europe.

Since the 1990s, many of these books have been translated into English, digitized, and put online.

Testimonies and Oral Histories

Right after the war, officials in DP camps and relief groups interviewed survivors. This was mainly to help them and to gather evidence for war crimes. These were some of the first recorded stories of Holocaust experiences.

Some of the first projects to collect witness stories started in the DP camps themselves. Camp newspapers like Undzer Shtimme ("Our Voice") published eyewitness accounts. One of the first books on the Holocaust, Fuhn Letsn Khurbn ("About the Recent Destruction"), was written by DP camp members and shared worldwide.

In the following decades, a big effort was made to record survivors' memories for the future. French Jews were among the first to create an institute for Holocaust documents. In Israel, the Yad Vashem memorial was officially started in 1953. It had already begun collecting Holocaust documents and personal stories from survivors.

The largest collection of testimonies was gathered at the USC Shoah Foundation Institute for Visual History and Education. It was founded by Steven Spielberg in 1994 after he made the film Schindler’s List. Its goal was to videotape the personal stories of 50,000 Holocaust survivors and witnesses. It reached this goal and more.

In 2002, a collection of Roma (Sinti and Roma) Holocaust survivor testimonies opened in Heidelberg, Germany.

Organizations and Gatherings

Many organizations have been created to help Holocaust survivors and their families. Right after the war, "Sh'erit ha-Pletah" helped with immediate needs in DP camps and fought for immigration rights. After these goals were met, the organization ended in the early 1950s. Later, survivors created local, national, and international groups to help with long-term physical, emotional, and social needs. Groups for specific people, like child survivors and their children, were also formed. From the late 1970s, conferences for survivors, their families, rescuers, and liberators began. These often led to permanent organizations.

Survivors

In 1981, about 6,000 Holocaust survivors met in Jerusalem for the first World Gathering of Jewish Holocaust Survivors.

In 1988, the Center of Organizations of Holocaust Survivors in Israel was created. It is a main organization for 28 survivor groups in Israel. It works for survivors' rights and welfare worldwide and with the Israeli government. It also helps remember the Holocaust. By 2020, it represented 55 organizations and survivors whose average age was 84.

Child Survivors

Child survivors of the Holocaust were often the only ones left from their entire families. Many were orphans. This group included children who survived in camps, in hiding with non-Jewish families, or in Christian homes. Some were sent to safety on Kindertransports or escaped with families to places like the Soviet Union or Shanghai. After the war, child survivors were sometimes sent to live with distant relatives who didn't always want them. They were sometimes mistreated. Their experiences and memories as child victims were often ignored.

In the 1970s and 80s, small groups of these survivors, now adults, started forming. They wanted to deal with their painful pasts in safe, understanding places. The First International Conference on Children of Holocaust Survivors happened in 1979. It was attended by about 500 survivors, their children, and mental health experts. It created a network for children of survivors in the U.S. and Canada.

The International Network of Children of Jewish Holocaust Survivors held its first international conference in New York City in 1984. Over 1,700 children of survivors attended. Their goal was to better understand the Holocaust and its impact, and to connect children of survivors.

The World Federation of Jewish Child Survivors of the Holocaust and Descendants was founded in 1985. It brings child survivors together and organizes activities worldwide. It holds yearly conferences in different cities. Children of survivors are also recognized as being deeply affected by their families' histories. Besides conferences, members speak about their survival, loss, and resilience. They talk about the bravery of Jewish resistance and the Righteous Among the Nations. They speak at schools and public events, take part in Holocaust Remembrance ceremonies, and fight against antisemitism and prejudice.

Children of Survivors

The "second generation of Holocaust survivors" refers to children born after World War II to parents who survived the Holocaust. Even though these children didn't directly experience the Holocaust, their parents' trauma often affected their upbringing and outlook. From the 1960s, children of survivors began exploring what it meant to be in this group. This helped broaden public discussion about the Holocaust.

Psychologists have studied how parents' terrible experiences affected their children. They looked at whether psychological trauma can be passed on to children, even if the children weren't there during the trauma. They also studied how this transfer of trauma showed up in the second generation.

Soon after "concentration camp syndrome" (or survivor syndrome) was described, doctors noticed in 1966 that many children of Holocaust survivors were seeking help in clinics in Canada. Grandchildren of Holocaust survivors were also much more likely to be referred to child psychiatry clinics.

One way psychologists describe communication in families with trauma is the "connection of silence." This means that in survivor families, there's an unspoken agreement not to talk about the parent's trauma. Parents do this not only to forget and adapt, but also to protect their children from the horrors they experienced.

Because of this, support groups have formed where children of survivors can explore their feelings with others who understand. Some second-generation survivors have also created local and national groups for support and to work on Holocaust issues. For example, the First Conference on Children of Holocaust Survivors in November 1979 led to support groups across the United States.

Many "second generation" members have found ways to move past their suffering and connect their experiences with their parents' history. For example, some work to remember the lives and communities destroyed during the Holocaust. They research Jewish history before the war, learn about the Holocaust, and help educate others. They fight against Holocaust denial, antisemitism, and racism. Some become politically active, working to find and prosecute Nazis or supporting Jewish and humanitarian causes. Others use creative ways like theater, art, and literature to explore the Holocaust and its effects on their families.

In April 1983, Holocaust survivors in North America created the American Gathering of Jewish Holocaust Survivors and their Descendants. The first event was attended by President Ronald Reagan and 20,000 survivors and their families.

Amcha, an Israeli center for psychological and social support for Holocaust survivors and the second generation, was established in Jerusalem in 1987.

Survivor Lists and Databases

One of the most famous and complete archives of Holocaust-era records, including lists of survivors, is the Arolsen Archives-International Center on Nazi Persecution. It was started by the Allies in 1948 as the International Tracing Service (ITS). For decades, its main job was to find out what happened to victims of Nazi persecution and search for missing people.

The Holocaust Global Registry is an online collection of databases. It's kept by the Jewish family history website JewishGen, which is part of the Museum of Jewish Heritage. It has thousands of names of survivors looking for family and families looking for survivors.

The Holocaust Survivors and Victims Database, kept by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, has millions of names of people persecuted by the Nazis. You can search for concentration camp or displaced persons camp lists by place or keywords.

The Benjamin and Vladka Meed Registry of Holocaust Survivors was created in 1981 by the American Gathering of Jewish Holocaust Survivors. It documents survivors' experiences and helps them find missing relatives and friends. It has over 200,000 records related to survivors and their families worldwide.

In 2019, Ancestry, a family history website, started working with the Arolsen Archives. They began digitizing millions of Holocaust and Nazi-persecution records and making them searchable online. This includes databases like "Africa, Asia and European passenger lists of displaced persons (1946 to 1971)" and "Europe, Registration of Foreigners and German Individuals Persecuted (1939–1947)".

The Holocaust Survivor Children: Missing Identity website helps child survivors who are still hoping to find relatives or learn about their parents and family. Others hope to find basic information about themselves, like their original names, birth dates, and parents' names, using a childhood photograph.

See also

- Aftermath of the Holocaust

- Armenian genocide survivors