Scranton general strike facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Scranton general strike |

|

|---|---|

| Part of the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 | |

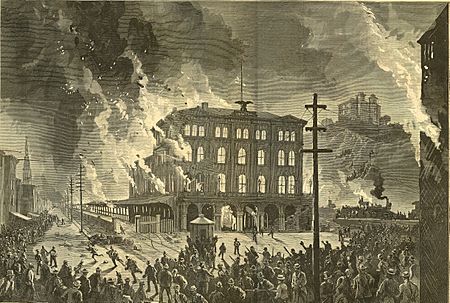

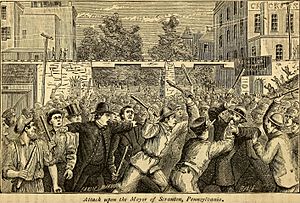

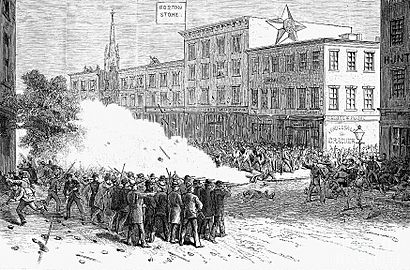

The Scranton Citizens' Corps fires on strikers, August 1, 1877, by Frank Leslie

|

|

| Date | July 23, 1877 – November 17, 1877 |

| Location | |

| Resulted in | Return to work, no concessions won |

| Casualties | |

| Death(s) | 4 |

| Injuries | 16–54 |

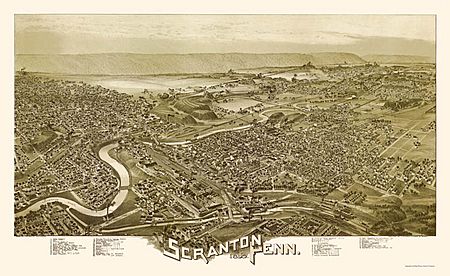

The Scranton general strike was a big work stoppage in 1877. It happened in Scranton, Pennsylvania, as part of the larger Great Railroad Strike of 1877. This strike was one of the last violent events during that time in Pennsylvania.

The strike started on July 23. Railroad workers stopped working to protest recent pay cuts. Within three days, thousands of workers from many different jobs joined the strike.

Many workers had gone back to their jobs when violence broke out on August 1. A large group of people attacked the town's mayor. Then, they clashed with the local militia, which is like a local army. Four people died, and many more were hurt.

State and federal troops were called to Scranton. They put the city under martial law, meaning the military took control. Small acts of violence continued. The last strikers returned to work on October 17. They did not win any of their demands. Many people involved in the August 1 shooting faced serious legal charges. Two people were also tried in lawsuits for criticizing the militia in newspapers. The local militia later became part of the Pennsylvania National Guard.

People have different ideas about why the strike started and why it became violent.

Contents

Why the Strike Started

The Long Depression was a time of economic trouble in the US. It began with the Panic of 1873. This crisis had a huge impact on American businesses. Over a hundred railroad companies closed in the first year. Building new train tracks dropped a lot, from 7,500 miles in 1872 to 1,600 miles in 1875.

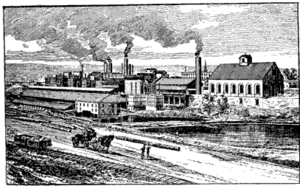

About 18,000 businesses failed between 1873 and 1875. The production of iron and steel dropped by as much as 45%. A million or more people lost their jobs. In 1876 alone, 76 railroad companies went bankrupt.

People were very unhappy because of these problems. On July 14, 1877, protests began in Martinsburg, West Virginia. They quickly spread to other states like Maryland, New York, Illinois, Missouri, and Pennsylvania. Violence broke out in Pittsburgh. Between July 21 and 22, 40 people were killed there. Over 1,000 train cars and 100 engines were destroyed. In Shamokin, Pennsylvania, 16 more people died in an uprising. Strikers also set fires in central Philadelphia.

Scranton's Situation Before the Strike

In 1874, mine owners in Scranton cut workers' pay by ten percent. Workers tried to start a strike, but it didn't work. For the next two years, the mines only ran part-time. In 1876, wages were cut again by fifteen percent. Still, efforts to organize a strike failed.

By the summer of 1877, tensions were very high. News of violence in other industrial cities spread. To make things worse, local mining companies again lowered wages. Railroad and factory owners also cut pay for their workers. One person said that Scranton had too many miners for the available work.

First Days of the Strike: July 23–25

On July 23, workers for the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad in Scranton made a request. They wanted their wages to go back to what they were before the recent 10% cut. The next day, July 24, at noon, 1,000 employees of the Lackawanna Iron and Coal Company peacefully walked off their jobs. They were not part of the railroad, but their pay had also been cut.

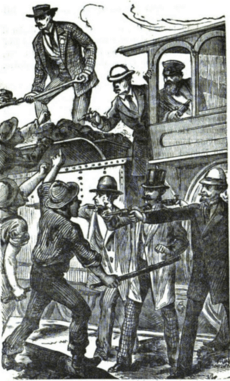

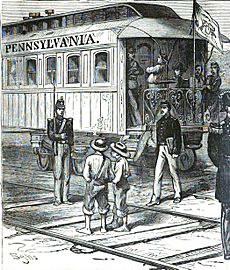

The railroad workers started their strike at 6:00 P.M. that same day. The railroad strike affected all other local businesses. Large amounts of goods could not be moved in or out of the city without trains. One man explained, "If the coal trains stop carrying coal, then mining coal must stop." The strikers allowed some passenger trains to pass. However, they did not let mail enter the city. That night, the strikers met and agreed to keep the city peaceful.

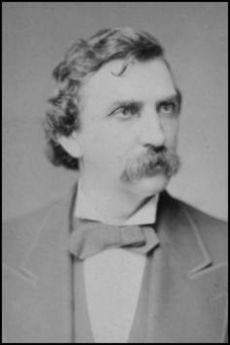

Mayor Robert H. McKune issued a public statement. He asked all good citizens to help keep the peace and follow the law. He also told people to avoid angry discussions about the strike. He mentioned the recent violence in Pittsburgh.

The Mayor warned that any damage to property would cost the city money. This would increase taxes for everyone. He said Pittsburgh had taken on a huge financial burden in just one day. He strongly urged everyone in Scranton to think carefully and avoid any quick, foolish actions.

On July 25, The New York Times reported that a general strike had begun in Scranton. A group representing the miners met with W. R. Storrs, a coal manager. They demanded higher wages. They also promised not to return to work, even if the railroad workers ended their strike. Brakemen, firemen, and others joined in. Almost every business in the city stopped, except for the Pennsylvania Coal Company.

The railway strikers held a large meeting. They decided to demand a 25 percent pay raise. They said this was "to supply ourselves and our little ones with the necessaries of life." General Manager William Walker Scranton replied that same day. He said he would love to raise wages, but it was "utterly impossible."

He explained that iron and steel prices were very low. Their steel works were closed because there was no work. He noted that workers' wages had not been cut for almost a year before this recent 10% cut. Meanwhile, the prices they got for iron and steel had dropped over twenty-five percent. He asked workers to think about whether some work was better than no work at all. He promised to pay higher wages when prices improved.

Middle Days of the Strike: July 26–30

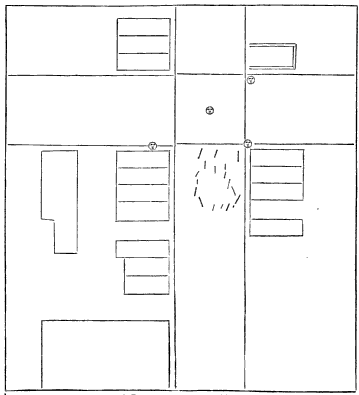

On the morning of July 26, Mayor McKune suggested forming an armed group of special police. This group would help keep order in the city. At that time, the local militia was in other parts of the state. They were dealing with railway strikes in Altoona, Harrisburg, and Pittsburgh. The new police group was later called the "Scranton Citizens' Corps." It had 116 members.

On July 27, Mayor McKune met with representatives from the Brotherhood of Trainmen. After a meeting of the railway strikers, the firemen and brakemen agreed to go back to work for their old wages. Soon after, the mill workers also returned to work. W. W. Scranton had given them assurances. However, the miners disagreed with this decision. They decided to continue their strike.

The Citizens' Corps gathered and chose their leaders. Ezra H. Ripple became their captain. Ripple got permission from General Osbourne, who led the Pennsylvania National Guard. This allowed the Corps to get weapons. Within three days, they had 350 guns and ammunition.

Rumors spread that the strike was losing strength. Volunteers and others not connected to the miners' union started operating the mine pumps. The miners had left these pumps, and they were needed to prevent the tunnels from flooding. There were some small acts of violence. The Citizens' Corps prepared for a possible fight. Members who had fought in the American Civil War trained the group. The Corps used a mine company store owned by W. W. Scranton as their main office. They had to move there after two other places refused them. The owners feared the Corps' presence would attract violence.

A report from Scranton on July 29 described the situation: "The entire Lackawanna region is idle. Last week, this area sent almost 150,000 tons of coal to market. Last week, it sent none. The situation here is very difficult, and we don't know when an outbreak will happen."

On July 30, Mayor McKune worked to resolve the situation. He promised the strikers that train traffic would start again, even if troops were needed. Because of his efforts, the strikers from the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western Railroad went back to work at their old wages. Messages were sent to New York City and Binghamton saying, "all was going to be right again."

The miners were angry that the railway workers had given up. Governor John F. Hartranft was told about the situation by the Mayor. He traveled from Harrisburg to Scranton with soldiers and regular troops. Some men, called "black-legs" (a term for strikebreakers), began to secretly go back to work.

The Violent Day: August 1st

On August 1, about 5,000 strikers gathered in an open area near the city's iron mills. This was at 8:00 a.m. They criticized those who had openly returned to work and those working in secret. During the meeting, an activist showed a fake letter. It claimed the Lackawanna Iron and Coal Company would cut wages to just $0.35 per day. W. W. Scranton, the company manager, later said this was false. But the rumor made the crowd very angry. Men yelled, "Go for the shops!" The crowd then moved towards the Lackawanna Iron and Coal facilities. They forced other workers out and injured some.

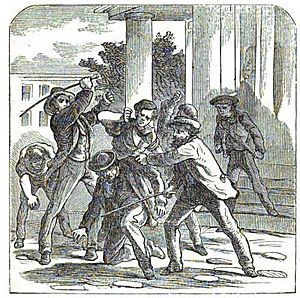

In response, W. W. Scranton led a group of his employees and the Citizens' Corps. Captain Ripple was out of town, so First Sergeant Bartholomew helped lead. The Mayor faced the crowd and told them to stop. But a man hit him, knocked him down, and badly hurt him. The crowd shouted, "The Mayor is killed!" However, he escaped with help from Father Dunn, who was then carried away by the crowd.

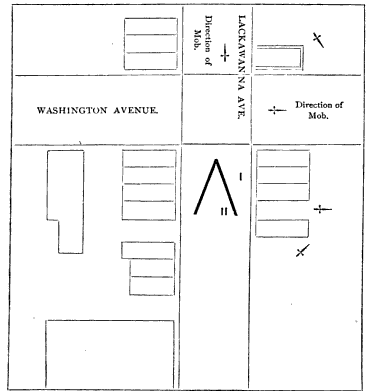

W. W. Scranton's group met the crowd near Washington Avenue. Bartholomew and his followers moved into the crowd. Several members of the Citizens' Corps were hit and knocked down by stones and clubs.

An order was given to fire, though it's unclear if everyone heard it. Three rounds of shots were fired into the crowd. The crowd quickly scattered. Four people were left dead or dying. Estimates of the wounded range from 16 to 54. Father Dunn returned to comfort those who were badly hurt.

Over 200 members of the Citizens' Corps were gathered. They were placed as guards along the streets. At 11:30 AM, Mayor McKune issued a new order: "I hereby order all places of business to be immediately closed. All good citizens should be ready to gather at my headquarters. This will be at the office of the Lackawanna Iron and Coal Company. The signal will be four long whistles from the gong at the blast furnaces."

He also sent a telegram to the Governor. The Governor replied that the National Guard brigade from Philadelphia was on its way. They had been returning home from stopping riots in Pittsburgh. Now, they were being sent to Scranton.

The night passed fairly quietly. Two spies were caught hiding in a lumber wagon. They were trying to find out how strong the Corps was and what they were doing. They were questioned and released. The Corps assured them they were ready for any attack. Early in the morning, an attack was attempted on W. W. Scranton's home. But patrols that had been sent out prevented it.

After the Violence: Conclusion and Legacy

On August 2, about 3,000 troops from the Pennsylvania National Guard arrived from Pittsburgh. They were led by Major General Robert Brinton. These troops put Scranton under martial law. On their way, the troops had arrested about 70 activists. They forced those arrested to fix damaged railroad tracks between the cities.

The Miner's Executive Committee opened a store for families. Local business people and farmers donated goods to help those suffering. Negotiations to end the strike continued. A newspaper article accused W.W. Scranton and the Corps members of serious crimes. This led to a meeting of local business people. They decided that the Corps members should be praised for their "courageous efforts" in stopping the crowd. They also promised to support them financially and otherwise. Governor Hartranft arrived in the city with his staff and 800 more men from the Pennsylvania National Guard. These were led by General Henry S. Huidekoper.

On August 3, W. W. Scranton wrote to the Philadelphia Times: "The strong determination of the strikers is clear. Even with powerful protection here, no miners have returned to work. The mine pumps are still run by bosses and clerks. They will be peaceful while the soldiers are here. But when the soldiers leave, they will have many complaints to deal with from their point of view."

On August 6, seven companies of United States Regulars joined the Pennsylvania State forces. These were led by Lieutenant Colonel Brennan. On August 9, the Third United States Infantry Regiment arrived, led by Lieutenant Colonel Henry Marrow. On August 10, General Huidekoper and his state forces left.

By October 8, some miners from the Pennsylvania Coal Company wanted to return to work. They had been forced to join the strike in July. But two days later, the only way to transport their coal was burned by the remaining strikers. By this time, "outrages" were happening daily. These included putting things on railroad tracks, burning buildings, shooting at watchmen and pump engineers at the mines, and stealing weapons.

On October 11, W. W. Scranton convinced some miners to return to work in the Pine Brook mine. He put up a notice saying that any miner who did not return to work the next day would lose their job. Many did return and worked under the guard of two companies of soldiers. That evening, word came that about 500 people were approaching the city. They intended to "fix the black legs" (strikebreakers) at Pine Brook. Guards were gathered at the mine and stood watch until morning. Every night after October 12, at the mayor's request, a 40-man guard was ready.

On October 16, the miners held a meeting. They all voted to return to work. They started working the next day. They had not won any of their demands. On October 19, the Governor told President Rutherford B. Hayes that the federal troops could leave. The Thirteenth Infantry left the city on October 31. Colonel Hartley's temporary forces left in November 1877.

Legal Cases After the Strike

In 1879, W. W. Scranton filed lawsuits against Aaron Augustus Chase and Judge William Stanton. Chase was the editor of the Scranton Daily Times. The lawsuits were about "inflammatory articles" published in 1878. These articles accused W. W. Scranton of serious crimes during the 1877 strike. These articles came out when people were trying to create a new Lackawanna County and make Scranton its main city.

Two separate trials were held. In September 1879, Chase was found guilty. He was fined $200 and sentenced to 30 days in prison. Stanton was found not guilty in his own trial that month. He had been forced to resign as a judge in February 1879.

What We Remember About the Strike

The Scranton general strike of 1877 is one of two major events in Scranton's labor history. The other is the 1902 Anthracite Strike.

In 2008, the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission placed a historical marker in Scranton. It remembers the 1877 strike. The marker says: "A riot occurred here on August 1, 1877. Armed citizens fired upon strikers, killing four. Many were injured, including Scranton's mayor. As in many US cities, this labor unrest was a result of the US depression of 1873 and a nationwide railroad strike in 1877."

Forming the Citizens' Corps

After the uprising, important people in Scranton wanted a permanent local military group. Within a week, almost a thousand dollars were raised for this purpose. On August 8, a meeting was held. They decided to form a four-company battalion, if the governor approved. On August 23, The Scranton Republican announced that the four companies had been formed. They would gather on September 11 for inspection by the governor. In 1878, the Pennsylvania government officially organized the group. It became the Thirteenth Regiment, Third Brigade, Pennsylvania National Guard. This group later took part in three other major strikes.

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |