Subprime mortgage crisis facts for kids

The American subprime mortgage crisis was a big financial problem that happened between 2007 and 2010. It was a major cause of the global financial crisis that started in 2007 and 2008. This crisis led to a very bad economic slowdown, where millions of people lost their jobs and many businesses went out of business. The U.S. government stepped in to help fix the financial system. They used programs like the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) and the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act.

The problem started when the U.S. housing bubble burst and interest rates went up. This meant a huge number of people could not make their mortgage payments. A mortgage is a loan used to buy a house. When people couldn't pay, it led to many foreclosures. A foreclosure is when the bank takes back a house because the owner didn't pay the mortgage. This also made housing-related investments, called housing-related securities, lose a lot of value.

Before the crisis, many of these housing loans were given to people with a higher risk of not paying them back. These were called subprime mortgages. Even though they were risky, financial companies packaged them into complex investments like mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and collateralized debt obligations (CDOs). These investments were given good ratings by rating agencies, making them seem safe.

The crisis became very clear in 2007, and by late 2008, several big financial companies failed. One of the most famous was Lehman Brothers, a large company that lent money for mortgages. It went bankrupt in September 2008. Many things caused the crisis. People blamed financial companies, government rules, credit agencies, and even people who took out loans. Two main reasons were the increase in subprime lending (lending to risky borrowers) and a lot of people buying houses just to sell them for profit, which is called speculation.

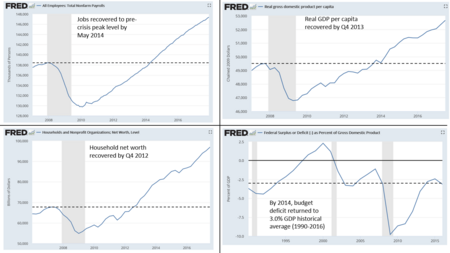

The crisis had serious and long-lasting effects. The U.S. economy went into a deep recession. About 9 million jobs were lost in 2008 and 2009. It took until May 2014 for the number of jobs to return to what it was before the crisis. The value of homes in the U.S. dropped by almost 30% on average.

Contents

How the Crisis Started and Unfolded

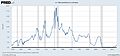

The main reason the crisis happened was the end of the United States housing bubble. This bubble peaked around 2006. During the bubble, it was easy to get loans, and house prices kept going up. This made people take out risky mortgages, hoping they could sell their homes quickly or get new loans with better terms. But when interest rates started to rise and house prices began to fall in 2006–2007, many people could not get new loans. This led to a huge increase in missed payments and foreclosures.

As house prices dropped, people around the world stopped wanting to invest in mortgage-related securities. In July 2007, a big investment bank called Bear Stearns announced that two of its investment funds had lost a lot of money. These funds had invested in mortgage-related securities. When these investments lost value, investors wanted their money back, which caused more selling and lower prices. This event was a key trigger for the financial problems that followed.

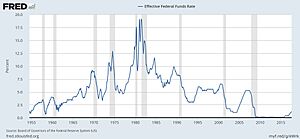

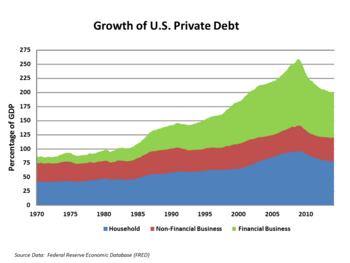

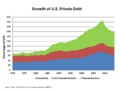

Other things also set the stage for the crisis. In the years before, a lot of money came into the U.S. from fast-growing countries in Asia and oil-producing countries. This money, along with low U.S. interest rates from 2002 to 2004, made it very easy to get credit. This helped create both a housing bubble and a credit bubble. People borrowed more money than ever before for mortgages, credit cards, and car loans.

Financial companies created many mortgage-backed securities (MBS). These investments got their value from mortgage payments and house prices. When house prices went down, big financial companies that had invested a lot in MBS reported huge losses. The crisis spread from the housing market to other parts of the economy, causing losses estimated in trillions of dollars worldwide.

During this time, the financial system became very fragile. Government officials did not fully understand how important certain financial companies, like investment banks and hedge funds (known as the shadow banking system), had become. These companies were not regulated in the same way as regular banks. They could also hide how much risk they were taking. This made the financial system very unstable.

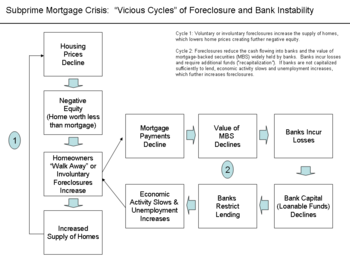

The losses suffered by financial companies made it harder for them to lend money, which slowed down the economy. Governments had to step in and bail out some key financial companies. This meant the government took on big financial risks.

The risks from the housing market downturn and financial crisis led central banks around the world to cut interest rates. Governments also started economic stimulus programs. Stock markets around the world were hit hard. Between January and October 2008, U.S. stock owners lost about $8 trillion.

Losses in the stock market and falling house values made people spend less, which further hurt the economy. Leaders from major countries met to figure out how to deal with the crisis. In the U.S., the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act was passed in July 2010 to try and prevent similar crises in the future.

What Caused the Crisis?

Many things led to the crisis over several years. Some of the main causes include:

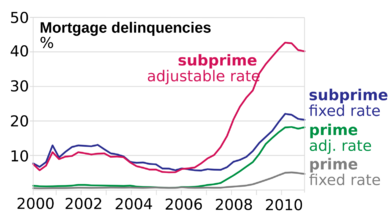

- Homeowners not being able to make their mortgage payments. This was often because their adjustable-rate mortgages had higher payments later on, or they borrowed too much.

- Too many homes being built during the housing boom.

- Risky mortgage products that made it easy for people to borrow more than they could afford.

- Financial products that spread the risk of mortgage defaults but also made it harder to see how risky things were.

- Government policies that encouraged people to buy homes, sometimes even if they couldn't truly afford them.

- People buying homes just to speculate (hoping to sell for a quick profit).

One big problem was that banks and financial companies were taking on too much risk. They were focused on making quick profits. Many experts believe that the idea that house prices would always go up was a major mistake.

The Housing Market Boom and Bust

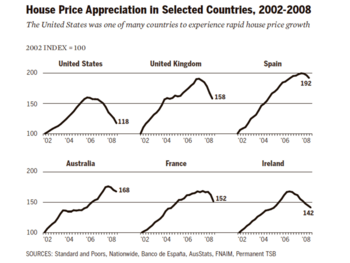

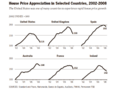

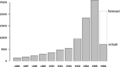

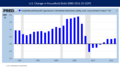

From 1997 to 2006, the price of a typical American house more than doubled. This was much faster than usual. People borrowed a lot more money, and their savings went down. This housing bubble was helped by low interest rates and a lot of foreign money coming into the U.S.

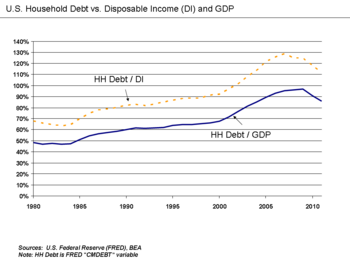

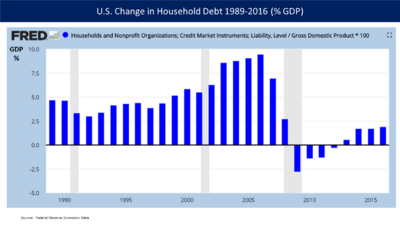

Many homeowners used the rising value of their homes to take out new loans or refinance their mortgages. By 2008, U.S. household debt was 134% of their yearly income. People were spending money they got from their home equity.

This huge increase in credit and house prices led to a lot of building. Eventually, there were too many unsold homes. This caused U.S. house prices to stop rising and start falling in mid-2006. Many people had adjustable-rate mortgages, which had low interest rates at first. They planned to refinance their loans when the low-rate period ended. But when house prices fell, it became very hard to refinance. People who couldn't refinance started to miss payments.

As more people stopped paying their mortgages, foreclosures increased. This put more unsold homes on the market, pushing prices down even further. This created a vicious cycle: falling prices led to more defaults, which led to more foreclosures, which led to even lower prices.

By September 2008, average U.S. housing prices had dropped by over 20% from their peak. Many homeowners had "negative equity", meaning their homes were worth less than their mortgages. This gave them a reason to stop paying their mortgages.

Risky Mortgage Loans and Lending Practices

Before the crisis, lenders changed how they gave out loans. They offered more and more loans to people who were higher risk. Lending rules became much looser between 2004 and 2007.

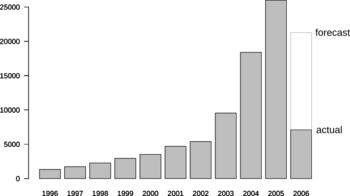

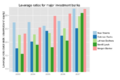

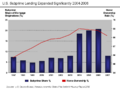

Subprime mortgages, which are loans to people with weaker credit, grew a lot. In 1994, they were 5% of all loans. By 2006, they were 20%. Lenders also offered riskier loan options. For example, in 2005, many first-time home buyers made very small or no down payments. In some cases, people could get loans without proving their income or assets, known as Ninja loans.

Some mortgages were "interest-only" or "payment option" loans. With these, homeowners paid only the interest, or even less than the interest, for a few years. After this initial period, monthly payments could double or triple. Many people with good credit scores were even given these risky subprime loans.

The rules for approving mortgages became very loose. Automated systems approved loans without proper checks. There was also a big increase in mortgage fraud by both lenders and borrowers.

The Shadow Banking System

The shadow banking system includes financial companies like investment banks and hedge funds that act like banks but are not regulated in the same way. This system grew very large, almost as big as traditional banking. However, it did not have the same safety rules.

These shadow banks were risky because they borrowed money for short periods to buy long-term, hard-to-sell assets. When the credit markets had problems, these companies were forced to sell their assets quickly at low prices. This made the financial system very unstable.

Many experts believe that the lack of rules for the shadow banking system was a core reason for the crisis. If these companies had been regulated like traditional banks, the crisis might not have been as bad.

Securitization and Complex Investments

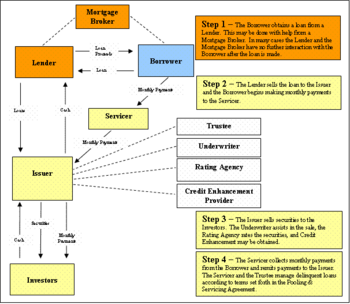

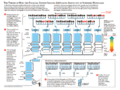

Securitization is when banks bundle many loans together to create new investments that can be bought and sold. This started with mortgages in the 1970s. Government-backed companies like Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac would buy safe mortgages, bundle them into "mortgage-backed securities" (MBS), and sell them to investors. They guaranteed these investments against default.

This "originate-to-distribute" model meant banks made money by creating and selling loans, not by holding them. This was different from the old "originate-to-hold" model where banks kept the loans and the risk. Securitization allowed banks to make more loans, but it also meant they didn't have to worry as much if the mortgages were paid back. This created a moral hazard.

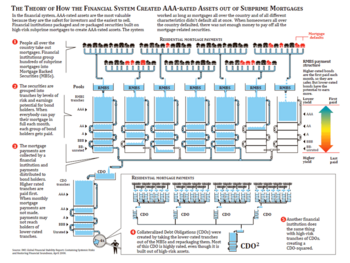

Investment banks wanted to get into this market. They created MBS from riskier subprime mortgages. They used "structured finance" to slice these bundled mortgages into different "tranches" or parts. The top tranches were supposed to be very safe and got the highest "triple A" credit ratings. This made them attractive to big investors like money market and pension funds.

To sell the riskier, lower-rated tranches, investment banks created another type of investment called a collateralized debt obligation (CDO). These CDOs bundled the leftover risky tranches. Amazingly, rating agencies often gave 70% to 80% of these new CDOs a triple-A rating too. This process was later called "ratings laundering" because it seemed to turn bad investments into good ones. People believed house prices would always rise, so they thought these models were safe.

When house prices fell, the models failed. Defaults were much higher and more connected than expected. This meant that if one mortgage defaulted, it often led to many others defaulting too.

Financial Company Debt and Incentives

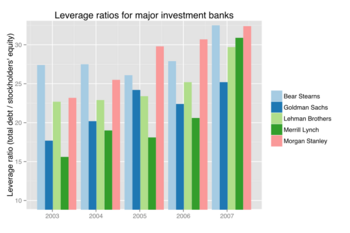

Many financial companies, especially investment banks, borrowed huge amounts of money between 2004 and 2007. They used this money to invest in mortgage-backed securities, betting that house prices would keep going up. This is called financial leverage. It's like someone taking out a second mortgage to invest in the stock market. This made them a lot of money during the boom, but it led to huge losses when house prices fell.

By 2007, the five biggest U.S. investment banks had over $4 trillion in debt. This meant they were very vulnerable. A small drop in the value of their assets could make them unable to pay their debts. In 2008, three of these big investment banks either went bankrupt (Lehman Brothers) or were sold cheaply (Bear Stearns and Merrill Lynch). The remaining two, Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs, became regular banks to get more government help.

Many financial companies also moved assets and debts "off-balance sheet" into special companies. This allowed them to avoid rules about how much capital they needed to hold. This increased their profits during the boom but led to bigger losses during the crisis.

The way financial workers were paid also played a role. Their bonuses were often based on how many financial products they created, not on how well those products performed over time. This encouraged them to take short-term risks and ignore long-term problems.

Credit Default Swaps

Credit default swaps (CDS) are like insurance for debt. Investors bought them to protect themselves if a borrower defaulted on a loan, especially on mortgage-backed securities. As banks lost money on subprime mortgages, it became more likely that those who sold CDS would have to pay out. This created a lot of uncertainty in the financial system.

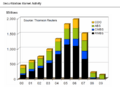

CDS contracts grew 100 times larger between 1998 and 2008. They were not well regulated. When Lehman Brothers went bankrupt in September 2008, no one was sure which companies would have to pay on the CDS contracts related to Lehman's debts.

American International Group (AIG), a large insurance company, had sold a lot of CDS. When mortgages defaulted, AIG didn't have enough money to pay its commitments. The U.S. government had to bail out AIG with over $100 billion.

Some experts said that CDS allowed people to bet many times on the same mortgage bonds. It was like many people buying insurance on the same house. This multiplied the effect of defaults and spread the problems throughout the financial system.

Inaccurate Credit Ratings

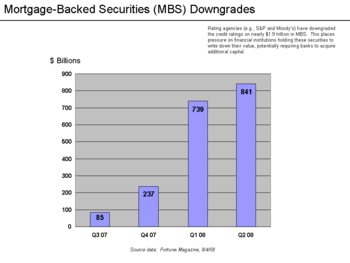

Credit rating agencies are companies that rate how risky debt investments are. During and after the crisis, these agencies were heavily criticized. They had given very high ratings to MBS and CDOs that were based on risky subprime mortgages. These investments later lost huge amounts of value.

Many investors relied on these ratings because they didn't understand the complex mortgage investments. The rating agencies were paid by the investment banks that created these securities. Critics say this created a conflict of interest. The agencies had an incentive to give higher ratings to please their clients, even if the investments were risky.

From 2000 to 2007, one major agency, Moody's, gave triple-A ratings to almost 45,000 mortgage-related investments. But as mortgages started to default, these agencies had to lower their ratings. By the end of 2008, 80% of the CDOs that had been rated "triple-A" were downgraded to "junk" status.

Experts believe these mistakes came from flawed computer models, pressure from financial companies, and a lack of proper oversight.

Impacts of the Crisis

The crisis had a huge impact on the U.S. and global economies.

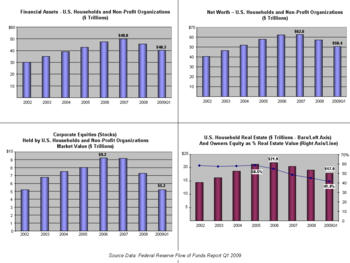

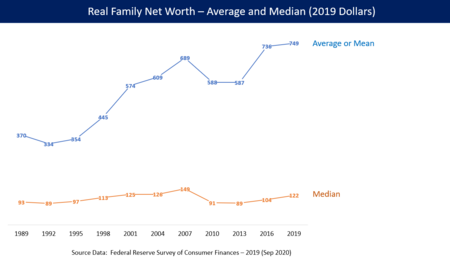

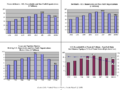

Between June 2007 and November 2008, Americans lost more than a quarter of their total wealth. The U.S. stock market fell 45% from its peak. Housing prices dropped 20%. Retirement savings and other investments also lost billions of dollars.

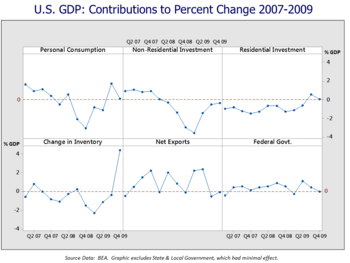

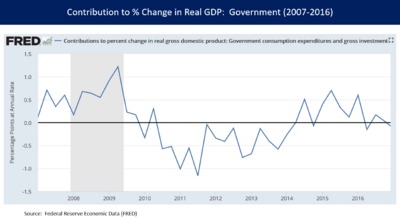

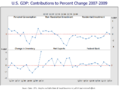

- The U.S. economy (GDP) shrank in late 2008 and didn't start growing again until 2010.

- The unemployment rate rose from 5% in 2008 to 10% by late 2009.

- Housing prices fell about 30% on average from mid-2006 to mid-2009.

- The total wealth of U.S. households dropped by $15 trillion, or 22%.

- U.S. national debt increased significantly.

Minority groups in the U.S. received more subprime mortgages and were hit harder by foreclosures. The crisis also badly affected the U.S. auto industry.

Responses to the Crisis

Governments and central banks took many actions to deal with the crisis.

Federal Reserve and Other Central Banks

The Federal Reserve, the central bank of the U.S., worked with other central banks around the world. They tried to keep money flowing in the markets and support the economy.

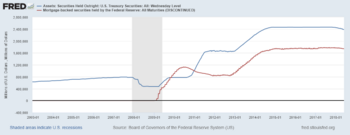

The Federal Reserve did several things:

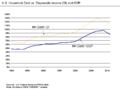

- It lowered interest rates very quickly, from 5.25% to almost zero (0-0.25%) by December 2008. These low rates stayed until December 2015.

- It lent money directly to banks and other financial companies.

- It started buying huge amounts of mortgage-backed securities and government bonds. This was meant to lower mortgage rates and help the economy.

The Federal Reserve basically created new money electronically to help the economy. They planned to reduce the money supply and raise interest rates once the economy recovered.

Economic Stimulus

In February 2008, President George W. Bush signed a $168 billion economic stimulus package. This mainly involved sending tax rebate checks directly to people.

In February 2009, President Barack Obama signed the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, a $787 billion stimulus package. It included a wide range of spending and tax cuts, with over $75 billion specifically for programs to help homeowners avoid foreclosure.

Bank Bailouts and Failures

Many major financial companies either failed, were bailed out by governments, or merged with other companies during the crisis. This happened because the value of their mortgage-backed investments dropped, making them unable to pay their debts.

The five largest U.S. investment banks, which had $4 trillion in debts, either went bankrupt (Lehman Brothers), were bought by other companies (Bear Stearns and Merrill Lynch), or were bailed out by the U.S. government (Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley). Government-backed companies Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac were also taken over by the federal government.

The U.S. government passed the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008 (TARP) in October 2008. This law provided $700 billion to help stabilize the banking system. Much of this money was used to buy shares in banks to boost their capital.

Homeowner Assistance

Both lenders and homeowners benefit from avoiding foreclosure. So, some lenders offered homeowners better mortgage terms, like refinancing or changing loan terms.

The U.S. government also launched programs to help homeowners. One example was the Homeowner Affordability and Stability Plan in 2009. This program aimed to help millions of homeowners avoid foreclosure by reducing their monthly payments.

However, many of these efforts were not as effective as hoped. Many homeowners who received help still ended up missing payments again.

Recovery After the Crisis

The recession officially ended in mid-2009. However, the economy continued to struggle for several years. Many economists called it the weakest recovery since the Great Depression.

This recession was different because it involved a banking crisis and people paying down huge amounts of debt. Recoveries from financial crises often take a long time, with high unemployment and slow economic growth.

By 2013-2014, several key economic measures, like job levels, economic output, and household wealth, had recovered to their pre-recession levels. All jobs lost during the recession were recovered by May 2014.

The government's bailout measures, which started under President Bush and continued under President Obama, were mostly completed and profitable by 2014. By January 2018, the government had recovered all the bailout funds, plus interest, making a profit.

Home Ownership by Young Adults After the Crisis

After the crisis, young adults (millennials) became more careful about mortgages. Many found it hard to find good jobs that would allow them to save enough for a house. This led to questions about whether owning a home is still a realistic goal for young people in the U.S.

While house prices fell during the recession, they have been steadily rising back up. With rising interest rates, home ownership continues to be a challenge for many young adults. The unemployment rate for young adults peaked at 14% in 2010. The rate of home ownership among young adults dropped significantly, and more young people ended up living with their parents.

Images for kids

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |