Pierre de Coubertin facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Pierre de Coubertin

|

|

|---|---|

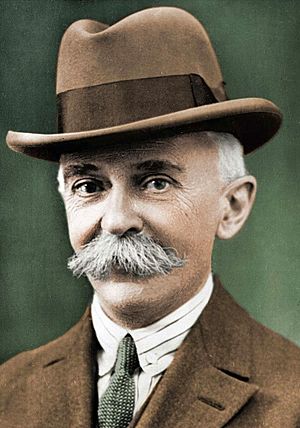

Pierre de Coubertin by the mid 1920s

|

|

| 2nd President of the International Olympic Committee | |

| In office 1896–1925 |

|

| Preceded by | Demetrios Vikelas |

| Succeeded by | Godefroy de Blonay (acting) |

| Honorary President of the IOC | |

| In office 1922 – 2 September 1937 |

|

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Vacant, next held by Sigfrid Edström (1952) |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Pierre de Frédy

1 January 1863 Paris, France |

| Died | 2 September 1937 (aged 74) Geneva, Switzerland |

| Spouse | Marie Rothan |

| Children | 2 |

| Alma mater | Paris Institute of Political Studies |

| Signature | |

| Olympic medal record | ||

|---|---|---|

| Art competitions | ||

| Gold | 1912 Stockholm | Literature |

Charles Pierre de Frédy, Baron de Coubertin (born Pierre de Frédy; 1 January 1863 – 2 September 1937), known as Pierre de Coubertin, was a French teacher and historian. He founded the International Olympic Committee (IOC) and was its second president. He is often called the father of the modern Olympic Games. He worked hard to bring sports into French schools.

Pierre de Coubertin came from a noble French family. He studied many subjects, especially education and history. He earned a law degree from the Paris Institute of Political Studies. It was there that he first thought about bringing back the Olympic Games.

The Pierre de Coubertin medal is a special award from the International Olympic Committee. It is given to athletes who show great sportsmanship during the Olympic Games. Many consider it the highest honor an Olympic athlete can receive.

Contents

Early Life and Family Background

Pierre de Frédy was born in Paris, France, on January 1, 1863. He was the fourth child in an aristocratic family. His parents were Baron Charles Louis de Frédy and Marie–Marcelle Gigault de Crisenoy. His family had a long history in France, with nobles and military leaders among his ancestors.

His father, Charles, was a talented artist whose paintings were shown in famous Parisian art shows. Pierre grew up during a time of big changes in France. These included the Franco-Prussian War and the start of the Third Republic.

Pierre's School Days

In 1874, his parents sent him to a new Jesuit school in Paris. He lived at the school, hoping to get a strong moral and religious education. Pierre was one of the best students in his class. He was also an officer in the school's special academy for top students. This shows he did well with the strict rules of his Jesuit education.

As a young aristocrat, Pierre could have chosen a career in the military or politics. Instead, he decided to become an intellectual. He spent his life studying and writing about many topics. These included education, history, literature, and sociology.

Pierre de Coubertin's Ideas on Education

Pierre de Coubertin was most interested in education. He focused on physical education and the role of sports in schools. In 1883, he visited England for the first time. There, he studied the sports program at the Rugby School, led by Thomas Arnold.

Coubertin believed these methods helped Britain become powerful in the 1800s. He wanted French schools to use similar programs. Adding physical education to French schools became a lifelong goal for him.

The Influence of English Schools

Coubertin thought that Thomas Arnold was a key figure in sports education. He wrote a book called L'Education en Angleterre in 1888 about his findings. He saw how "organized sport can create moral and social strength" in English schools. He believed that sports helped balance the mind and body. They also kept young people from wasting their time.

He felt that the ancient Greeks had understood this approach to education. He believed the rest of the world had forgotten it. He dedicated the rest of his life to bringing it back.

Connecting to Ancient Greece

As a historian, Coubertin loved the idea of ancient Greece. When he thought about physical education, he looked to the Athenian idea of the gymnasium. This was a training place that helped both physical and mental growth. He saw a "triple unity" there: between old and young, between different subjects, and between people who did theoretical work and those who did practical work. Coubertin wanted schools to adopt this idea.

Coubertin's ideas about physical education were also practical. He thought that physically educated men would be better soldiers. They would be better prepared for wars, like the Franco-Prussian War, which France had lost. He also saw sports as democratic, bringing different social classes together through competition.

Unfortunately, his efforts to add more physical education to French schools did not succeed. However, this failure led him to a new idea: bringing back the ancient Olympic Games. He wanted to create a big international sports festival.

Bringing Back the Olympic Games

Thomas Arnold was important to Coubertin's educational ideas. But his meetings with William Penny Brookes also shaped his thoughts on sports. Brookes, a doctor, believed exercise prevented illness. In 1850, he started local sports events called "Meetings of the Olympian Class" in England.

Brookes tried to get the Olympic Games revived internationally. He even talked with the Greek government. In Greece, rich cousins Evangelos and Konstantinos Zappas funded Olympics within Greece. They also paid to restore the Panathinaiko Stadium, used in the 1896 Summer Olympics. While others had ideas for Olympic contests, Coubertin's work led to the International Olympic Committee and the first modern Olympic Games.

The Idea Takes Shape

In 1889, Coubertin had the idea to revive the Olympic Games as an international event. He spent the next five years planning a meeting of athletes and sports fans. Brookes learned of Coubertin's plans and wrote to him in 1890. They began to exchange letters about education and sports. Brookes helped Coubertin by using his connections with the Greek government.

Coubertin believed the ancient Olympics encouraged competition among amateur athletes. He saw value in this. He also thought the ancient idea of a sacred truce during the Games could promote peace today. He felt that sports helped people from different cultures understand each other, reducing the risk of war. He also believed that the effort to compete was more important than winning.

The 1894 Congress in Paris

Coubertin worked to create a national sports association in France. This was the Union des Sociétés Françaises de Sports Athlétiques (USFSA). In November 1892, Coubertin first publicly suggested bringing back the Olympics. His speech was well-received, but people were not fully committed to his big idea.

Despite challenges, the USFSA planned an international conference. The congress was held on June 23, 1894, at the Sorbonne in Paris. Participants split into two groups: one on amateurism and one on reviving the Olympics.

A Greek participant, Demetrios Vikelas, led the Olympic group. He later became the first President of the International Olympic Committee. This group suggested that the Olympic Games be held every four years. They also decided the games should feature modern sports, not ancient ones. They set the first modern Olympic Games for Athens, Greece, and the second for Paris.

Coubertin had worried about Greece's ability to host the games. But Vikelas convinced him to support Athens. The congress agreed to all proposals, and the modern Olympic movement officially began.

Challenges and Successes

After the Congress, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) was formally created. Demetrios Vikelas became its first president. The IOC focused on planning the 1896 Athens Games. Coubertin helped by offering technical advice. He also planned the list of events.

The Greek organizers were sometimes frustrated with Coubertin. They wanted to keep the Games in Athens every four years, which Coubertin did not want. The problem was solved when Coubertin suggested to the King of Greece that he hold Pan-Hellenic games between Olympiads. The King agreed.

Coubertin became IOC president after Vikelas stepped down in 1896. The Olympic movement faced tough times after that. The 1900 Games in Paris and the 1904 Games were overshadowed by big World's Fairs in the same cities. They did not get much attention.

Leading the IOC

The 1906 Summer Olympics helped the movement gain momentum again. The Olympic Games became the world's most important sports competition. Coubertin created the modern pentathlon for the 1912 Olympics.

He stepped down as IOC president after the 1924 Olympics in Paris. These games were much more successful than the 1900 attempt. Henri de Baillet-Latour became the new president in 1925.

Olympic Gold Medal for Literature

Coubertin won a gold medal for literature at the 1912 Summer Olympics. He won for his poem called Ode to Sport. He used a fake name, Georges Hohrod and M. Eschbach, for his entry. These were names of villages near his wife's birthplace.

Other Interests and Legacy

Scouting Movement

In 1911, Pierre de Coubertin founded a Scouting organization in France. It was called Éclaireurs Français (EF). This group later joined with others to form the Éclaireuses et Éclaireurs de France.

Personal Life and Family

In 1895, Pierre de Coubertin married Marie Rothan. They had two children. Their son, Jacques (1896–1952), became ill as a child. Their daughter, Renée (1902–1968), had emotional problems and never married.

Coubertin died from a heart attack in Geneva, Switzerland, on September 2, 1937. He was buried in Bois-de-Vaux Cemetery in Lausanne. Marie died in 1963. Pierre was the last person with his family name.

Enduring Olympic Symbols

The traditional Olympic motto is Citius, Altius, Fortius. This means "Faster, Higher, Stronger." Coubertin suggested it in 1894. It became official in 1924. In 2021, it was changed to Citius, Altius, Fortius – Communiter, meaning "Faster, Higher, Stronger – Together." The original motto was created by Henri Didon, a friend of Coubertin.

The Pierre de Coubertin medal is given to athletes who show true sportsmanship. Many athletes and fans see it as the highest Olympic honor.

A minor planet, 2190 Coubertin, was found in 1976 and named after him. The street where the Olympic Stadium in Montreal is located is named Pierre de Coubertin Avenue. This stadium hosted the 1976 Summer Olympic Games. It is the only Olympic stadium on a street named after him.

In 2007, he was added to the World Rugby Hall of Fame for his contributions to rugby union.

What Some Scholars Say

Some experts have looked closely at Coubertin's ideas. For example, David C. Young believes that ancient Olympic athletes were not always amateurs, as Coubertin thought. This is a topic scholars still discuss.

Young also suggests that efforts to limit international sports to amateur athletes, which Coubertin supported, might have given upper classes more control over sports. However, Coubertin's supporters say he did not intend any class differences.

It is clear that Coubertin's romantic view of the ancient Olympic Games was different from what history shows. For example, his famous idea that "participation is more important than winning" was not the main goal for the ancient Greeks.

Coubertin also believed the Games would bring peace. But the peace he spoke of only allowed athletes to travel safely. It did not stop wars from starting or ending ongoing ones.

Some scholars also question how much Coubertin actually planned the 1896 Athens Games. They suggest he played a smaller role than he claimed.

Coubertin also spoke against women's sports. He said a "female half-Olympiad" would be "impractical, uninteresting, unaesthetic, and... incorrect."

List of Works

Pierre de Coubertin wrote many books and articles. Here are some of his books:

- Une Campagne de 21 ans. Paris: Librairie de l'Éducation Physique. 1908.

- Coubertin, Pierre de (1900–1906). La Chronique de France (7 vols.). Auxerre and Paris: Lanier. pp. 7 v. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/000045959.

- L'Éducation anglaise en France. Paris: Hachette. 1889. https://archive.org/details/leducationangla00coubgoog.

- L'Éducation en Angleterre. Paris: Hachette. 1888. https://archive.org/details/lducationenangl00coubgoog.

- Essais de psychologie sportive. Lausanne: Payot. 1913.

- L'Évolution française sous la Troisième République. Études d'histoire contemporaine. Paris: Hachette. 1896. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/000648722.

- France Since 1814. New York: Macmillan. 1900. https://archive.org/stream/francesince181400coubrich#page/n5/mode/2up.

- La Gymnastique utilitaire. Paris: Alcan. 1905. https://archive.org/details/BIUSante_79935.

- Histoire universelle (4 vols.). Aix-en-Provence: Société de l'histoire universelle. 1919.

- Mémoires olympiques. Lausanne: Bureau international de pédagogie sportive. 1931.

- Notes sur l'éducation publique. Paris: Hachette. 1901. https://archive.org/details/notessurlducati01coubgoog.

- Pages d'histoire contemporaine. Paris: Plon. 1908.

- Pédagogie sportive. Paris: Crés. 1922.

- Le Respect Mutuel. Paris: Alean. 1915.

- Souvenirs d'Amérique et de Grèce. Paris: Hachette. 1897.

- Universités transatlantiques. Paris: Hachette. 1890. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/006509997.

See also

In Spanish: Pierre de Coubertin para niños

In Spanish: Pierre de Coubertin para niños

- Statue of Pierre de Coubertin, Tokyo

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |