Epping Forest facts for kids

| Site of Special Scientific Interest | |

Epping Forest near Epping

|

|

| Area of Search | Greater London Essex |

|---|---|

| Grid reference | TL475035 to TQ 405865 |

| Interest | Biological |

| Area |

|

| Notification | 1990 |

| Location map | Magic Map |

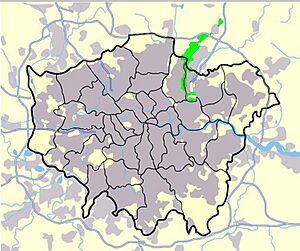

Epping Forest is a huge natural area of about 2,400 hectares (5,900 acres) with ancient woodlands and other habitats. It sits on the border between Greater London and Essex. The main part of the forest stretches from Epping in the north down to Chingford near London. South of Chingford, it becomes a green path reaching into east London as far as Forest Gate. People sometimes call it the "Cockney Paradise" because it's a big green space close to London. It's actually the largest forest in London!

The forest is on a high ridge between the Lea and Roding valleys. It has woodlands, grasslands, open heath, streams, bogs, and ponds. Because of its height and thin, gravelly soil, it wasn't great for farming in the past. Historically, many local landowners owned parts of the forest, but local people (called commoners) had rights to use it for things like grazing animals and collecting firewood. It was also a "royal forest," which meant only the king could hunt deer there.

Today, many visitors come to the forest from the nearby cities, which can put a strain on its natural environment. However, these local visitors were also key to saving the forest in the late 1800s. Back then, there was a plan to divide up and destroy parts of the forest. A huge public outcry led the City of London Corporation to buy and protect the land. This was a major success for the environmental movement in Europe! The City of London Corporation still owns and manages the forest today.

When the forest was first saved, the people in charge didn't fully understand how humans had shaped its ecosystems over time. They stopped some traditional practices, like cutting trees in a special way called "pollarding," and allowed animal grazing to decrease. This changed the forest and led to less variety of plants and animals. Today, the people who manage the forest know about these past mistakes and are trying to bring back some of the old ways to help the forest thrive again.

The forest is so important that it gave its name to the Epping Forest local government district and to Forest School, a private school in Walthamstow.

Contents

The Story of Epping Forest

Ancient Times

The area we now call Epping Forest has been covered in trees for a very long time, since the Neolithic period (Stone Age). You can still find the remains of two Iron Age hill forts, called Loughton Camp and Ambresbury Banks, hidden in the woods. Studies of plant pollen show that even when people lived in these forts, it didn't significantly change the amount of woodland.

However, the forest did change over time. The trees that grew here long ago, like small-leaved lime, were replaced during the Anglo-Saxon period. This might have happened because people were selectively cutting down certain types of trees. Today, the forest is mostly made up of beech and birch trees, or oak and hornbeam trees. This mix probably came about from some forest clearing that happened in Saxon times.

How the Forest Was Managed

Around the 12th century, during the time of King Henry II, this area became a "royal forest." This was a legal term, meaning that special "Forest Law" applied, and only the king had the right to hunt deer there. It didn't mean the whole area was covered in trees; much of the original Forest of Essex was actually farmland.

Over many years, the Forest of Essex became smaller as parts of it were removed from Forest Law. It was replaced by smaller forests, including Waltham Forest. This Waltham Forest included the areas that later became Epping Forest and Hainault Forest.

Physically, the forest probably looked similar to its modern size by the early 1300s. When the Black Death arrived in England in 1348, it caused a huge drop in population. This meant there was less pressure on the woods and common lands, leading to a long period where these areas stayed stable in size. At that time, the forest reached a bit further south, to the Romford Road in Forest Gate.

Later, most of Waltham Forest was legally "deforested," meaning it was no longer under Forest Law. This left two smaller, heavily wooded areas: Epping Forest and Hainault Forest. The name "Epping Forest" was first used in the 1600s.

Even though the king had hunting rights, the land itself was owned by many local landowners. It was managed as "common land," where landowners had certain rights, and local people (commoners) had rights too. Commoners could gather firewood, graze their livestock, and let their pigs eat acorns and nuts. The forest was mostly a mix of wooded pastures and open plains, not just thick woods, and cattle grazed in both areas.

Queen Elizabeth's Hunting Lodge

During the Tudor period, kings and queens like Henry VIII and Queen Elizabeth I might have hunted in the forest, though we don't have clear records. In 1543, Henry VIII ordered a building called Great Standing to be built at Chingford so he could watch the hunt. This building was updated in 1589 for Queen Elizabeth I and is still there today. It's now known as Queen Elizabeth's Hunting Lodge and is open to visitors. Another old hunting stand is now part of the forest's main office at The Warren in Loughton.

From the 1600s to the 1800s

After the king returned to power in 1660, royal hunting in the forest stopped, even though deer were brought back. The forest then became important for providing timber for the Royal Navy to build ships. This continued until about 1725, when most of the suitable oak trees had been cut down.

The City of London kept up an old tradition of an Easter Monday stag hunt in the forest, but official involvement ended in 1807. By 1827, a huntsman chased a forest stag all the way to West Ham. The traditional Easter Monday hunt became a big, lively event for ordinary Londoners. They would gather at Fairmead Oak to chase a stag that had been captured and then released. The stag usually got away safely. The last of these hunts was in 1882, and it ended in a riot that the police had to break up.

In the 1830s, the forest faced its first major change in centuries when a new road, the Epping New Road, was built through it. This road, completed in 1834, helped shorten the journey from Woodford Green to Epping. It was once part of the A11 and is now part of the A104.

With new railway stations opening near the forest in the 1850s, more and more working-class people from East London started visiting the forest for fun on Sundays and holidays. Others arrived by horsebus. On one day in 1880, a committee estimated that up to 400,000 people had visited Epping Forest!

Saving the Forest from Enclosure

In the early 1800s, the Lord Warden of Epping Forest allowed about 3,000 acres of forest land to be "enclosed" by local landowners. This meant the land was fenced off and taken out of public use. The government also wanted to enclose land for farming and building.

In 1851, nearby Hainault Forest was privatized, and most of its trees were removed to create poor farmland. People were very upset about this destruction. This anger helped start the modern conservation movement, which aimed to protect Epping Forest. Epping Forest was harder to enclose because many different people owned parts of it, but individual landowners still tried to take over sections. As nearby areas became more urban, the forest's importance for public recreation grew. This led to the creation of the Open Spaces Society in 1865, which worked to protect common lands around London.

By 1870, the open forest had shrunk to only about 3,500 acres. One landowner, Reverend John Whitaker Maitland, had enclosed 1,100 acres. He had a long argument with a commoner named Thomas Willingale and his family, who insisted on their right to cut branches from trees (called "lopping"). In 1866, Willingale's son and nephews were fined and jailed for damaging Maitland's trees. Willingale was encouraged to continue his fight by Edward Buxton and others from the Commons Preservation Society.

In July 1871, about 30,000 East Londoners protested on Wanstead Flats against fences put up by Earl Cowley. Despite clashes with police, the crowd broke down the fences. This event got national attention. At this point, the City of London Corporation got involved. They had bought land nearby in 1853, which gave them the right to graze cattle in the forest. In 1871, the City sued 16 landowners, saying the enclosures violated their ancient grazing rights. After a court ruling in 1874, all enclosures made since 1851 were declared illegal.

Following this, two laws in 1871 and 1872 allowed the City to buy the 19 forest manors. Thanks to this victory, only 10% of Epping Forest was lost to enclosure, compared to 92% of Hainault Forest.

Under the Epping Forest Act 1878, the forest stopped being a royal forest and was bought by the City of London Corporation. Their Epping Forest Committee now acts as the "Conservators" (protectors) of the forest. This committee includes members from the City of London and four "Verderers," who are local residents elected by the commoners. A Superintendent and twelve "Epping Forest Keepers" manage the forest day-to-day. The Act also ended the Crown's right to deer meat and stopped pollarding trees, though grazing rights continued. This law stated that the Conservators "shall at all times keep Epping Forest unenclosed and unbuilt on as an open space for the recreation and enjoyment of the people." This was the first major win for the modern conservation movement in Europe.

"The People's Forest"

When Queen Victoria visited Chingford on May 6, 1882, she famously said, "It gives me the greatest satisfaction to dedicate this beautiful forest to the use and enjoyment of my people for all time." From then on, it became known as "The People's Forest." The City of London Corporation still manages Epping Forest according to the Epping Forest Act. They use their own private funds, not local taxes, to care for it. The Conservators work from The Warren, which includes the historic Warren House in Loughton.

Until 1996, commoners still had the right to graze cattle, and herds would roam freely in the southern part of the forest every summer. Cattle were brought back in 2001, but their movements are now more controlled to avoid traffic problems. Commoners who live in a Forest parish and own at least 0.5 acres of land can still register and graze cattle during the summer.

The right to collect wood still exists, but it's rarely used. It's limited to one bundle of dead or driftwood per day for each adult resident.

Butler's Retreat is a historic building from the mid-1800s, originally a barn. It's one of the few remaining Victorian "retreats" in the forest. Located next to Queen Elizabeth's Hunting Lodge, it's named after John Butler, who ran it in 1891. These retreats originally served non-alcoholic drinks as part of the Temperance movement. After closing in 2009, the building was renovated and reopened as a café in 2012.

On July 12, 2012, The Duke of Gloucester, who is the official Epping Forest Ranger, opened The View visitor centre at Chingford. This building, an old Victorian coach house, along with Queen Elizabeth's Hunting Lodge and Butler's Retreat, forms the Epping Forest Gateway.

Forest Geography

Epping Forest is about 19 kilometers (12 miles) long from north to south. However, it's not very wide, usually no more than 4 kilometers (2.5 miles) at its widest point, and often much narrower. The main part of the forest stretches from Epping in the north to Chingford on the edge of London. South of Chingford, it becomes a narrow green strip that goes deep into East London, reaching Forest Gate. The southern part of the forest was always thinner, but more land was lost there in the 1800s and 1900s. The very southernmost part of the forest today is Wanstead Flats.

The forest sits on a higher area of land called the Epping Forest Ridge. This ridge is between the valleys of the Lea and Roding rivers. These valleys were carved out by glaciers during the last ice age, around 18,000 BC. The ridge is made of clay and loam, with gravel at its southern end. The highest points are near Ambresbury Banks, south of Epping, which is 111 meters (384 feet) above sea level. Pole Hill near Chingford reaches 91 meters (299 feet).

Here is a simple list of different parts of Epping Forest, starting from the north:

- Lower Forest: A triangle of oak and hornbeam trees just north of Epping town.

- Bell Common and Epping Thicks: The forest area directly south of Epping. Bell Common has a cricket pitch, and the M25 motorway runs underneath in a tunnel. Epping Thicks is where the Ambresbury Banks Iron Age fort is located.

- Genesis Slade: An area of beech, oak, and hornbeam trees on the eastern edge of the forest near Theydon Bois.

- Great Monk Wood: A large area of beech and hornbeam trees that crosses the Epping New Road, reaching the edge of Loughton.

- High Beech: An open, sandy ridge on the western side of the forest, offering views towards Waltham Abbey and the Lea Valley.

- Bury Wood and Chingford Plain: The southwestern part of the main forest that extends to Chingford. The plain here includes a golf course.

- Knighton Wood and Lords Bushes: A separate area of forest at Buckhurst Hill. Knighton Wood was once a landscaped park and was added to the forest in 1930.

- Hatch Forest and Highams Park: A strip of forest that goes south from Chingford along the River Ching. Highams Park Lake was designed in 1794 and added to the forest in 1891.

- Woodford Green: An area of grassy land with trees, including a cricket pitch.

- Walthamstow Forest and Gilbert's Slade: A continuation of the forest south from Woodford Green, crossing the North Circular Road and heading towards Whipps Cross.

- Leyton Flats: Stretches between Snaresbrook, Whipps Cross, and Leytonstone. It's mostly open grassland with the Eagle and Hollow Ponds.

- Bush Wood and Wanstead Flats: Extends east from Leytonstone towards Forest Gate and Manor Park. Mostly open grassland with football pitches and several ponds.

- Wanstead Park: A fenced-off part of the forest with limited opening hours. It used to be the landscaped park of Wanstead House, which was torn down in 1825. The park was added to the forest in 1880.

Forest Ecology and Habitats

The forest's age and the many different habitats it contains make it a very important place for wildlife. It's officially recognized as a Site of Special Scientific Interest. Its past use as common land, with wooded pastures and open plains, has greatly shaped its natural environment. While the Epping Forest Act saved the forest, it also had some negative effects on the variety of life there.

Wood Pasture

The way the land was used historically has had a huge impact on the forest's look and ecology. This is especially clear with the "pollarded" trees. These trees were regularly cut back to a main trunk (called a "bolling") every 13 years or so. The cut was made above where grazing animals could reach. However, since the Epping Forest Act, the pollards haven't been cut. Now, they have massive crowns of thick, trunk-like branches and very large bolls. This gives them a unique appearance, different from trees in other forests. Sometimes, the heavy branches can't be supported by the tree itself. The large amount of dead wood in the forest provides homes for many rare types of fungi and insects. Epping Forest has 55,000 "ancient trees," which is more than any other single place in the United Kingdom.

The most common tree species are Pedunculate oak, European beech, European hornbeam, silver birch, and European holly. Some plants that show the woodland has been undisturbed for a long time include service-tree, butcher's-broom, and drooping sedge.

When trees were pollarded, more light reached the forest floor, allowing many low-growing plants to thrive. Since the Act, the huge crowns of the pollards block most of the light, which has changed the plants that grow underneath.

Plains

The open plains were usually found in wet or low-lying areas. Today, the area around the forest is mostly urban. Because there's less grazing by animals now, some former grasslands and heathlands have become covered by "secondary woodland" (new trees growing where they weren't before).

Restoration Work

In recent years, the Conservators have been trying out pollarding again in certain parts of the forest. They've cut back some old pollards and even created new ones, with mixed results. A herd of English Longhorn cattle has also been brought back to graze the heathland and grassland.

Lakes and Ponds

There are over 100 lakes and ponds in the forest, all different sizes and ages. They are important homes for many kinds of animals and plants. Many of them were made by people, mostly from digging out gravel. Some were created as part of landscape designs, and a few were even formed by bombs and V-2 rockets during the Second World War. You can go angling (fishing) in 24 of the lakes and ponds, where you can catch many types of freshwater fish. All the lakes and ponds are open to the public and are located near forest paths.

Forest Animals

The forest is home to a wide variety of animals, including fallow deer, muntjac deer, and the European adder snake.

Deer in Epping Forest

The fallow deer in Epping Forest are unusual because they are often black. They might be descended from black deer given to King James I in 1612, though black deer were seen in England even earlier. By 1878, when the Epping Forest Act protected the deer, poaching had reduced the herd to just twelve female deer and one male. However, their numbers grew to about 200 by the early 1900s. In 1954, it was noticed that common lighter-brown fallow deer were interbreeding with the black ones. Some black deer were sent to Whipsnade Zoo to help preserve this special variety. Later, to protect the deer from traffic and dogs, an enclosed deer sanctuary of 109 acres was created near Debden. This sanctuary helps maintain a healthy population of deer that can be released back into the forest if numbers get too low.

Red deer used to live in Epping Forest, but the last ones were moved to Windsor Great Park in the late 1800s. The last time a roe deer was seen in the forest was in 1920. In recent decades, Reeves's muntjac deer have been reported in the southern part of the forest. In 2016, there was some debate when it was announced that fallow deer and muntjac would be culled (controlled) in areas around the forest. Local residents were concerned, but environmentalists said it was necessary to prevent too much grazing of the plants on the forest floor.

Forest Protection and Planning

- Most of the forest, an area of 1,728 hectares (4,270 acres), is a Site of Special Scientific Interest. This means it's protected for its important natural features.

- The forest is also a Special Area of Conservation, which is an even higher level of protection for its habitats and species.

- Much of the Forest is part of the Metropolitan Green Belt, which aims to stop urban areas from spreading too much.

- A large part of the Forest is also called Metropolitan Open Land, meaning it's protected as open space within the city.

Fun Things to Do in the Forest

Many different activities are popular in Epping Forest, especially walking, cycling, and horse riding.

Epping Forest attracts many mountain bikers. You can generally ride bikes there, except in sensitive areas like the Iron Age camps or Loughton Brook, where riding could cause damage. Even with clear signs, some bikers and horse riders still cause damage in these areas, which concerns the forest managers. Many clubs organize rides, especially on Sunday mornings. The forest is also a training ground for many national mountain bike racers because it has fast and challenging trails. Epping Forest was even considered as a possible location for the mountain biking event at the 2012 Summer Olympics. In 2014, Stage 3 of the 2014 Tour de France cycling race passed through the forest.

Horse riding is also very popular. Riders need to register with the Epping Forest Conservators before they can ride in the forest. Running for fun in Epping Forest has been happening almost since the sport began in the 1870s. The first English Championships for running were even held here in 1876. Orienteering (a sport using a map and compass) and rambling (long walks) are also popular. Many guidebooks offer shorter walks for visitors. A big event for walkers is the traditional Epping Forest Centenary Walk, which happens every year in September. It celebrates the saving of Epping Forest as a public space.

High Beach in Epping Forest was the first place in Britain to host motorcycle speedway races, starting on February 19, 1928. The track was behind The King's Oak pub and attracted large crowds. It closed after World War II when a swimming pool was added to the pub. However, fans and former racers still gather there every year around February 19. You can still see parts of the old track today. The Epping Forest Field Centre, located in the forest, offers various courses about nature.

There are 60 football pitches with changing rooms on Wanstead Flats, which are used by amateur and youth teams. There's also a public 18-hole golf course at Chingford Plain, used by several golf clubs. This course was set up in the forest in 1888. Cricket is played on forest land at Woodford Green, Bell Common (Epping), Buckhurst Hill, and High Beach. An old cricket match from 1732, between London Cricket Club and an Essex & Hertfordshire team, is recorded in the forest.

Visitor Centres

The forest has three visitor centres where you can learn more:

- Epping Forest Visitor Centre at Paul’s Nursery Road, High Beach, managed by the Epping Forest Heritage Trust.

- Epping Forest Gateway at Ranger's Road, Chingford.

- The Temple in Wanstead Park.

Getting There by Public Transport

You can reach most places in and around the forest using public transport. The forest is easy to get to from many London Underground Central Line stations between Leytonstone and Epping. You can also use London Overground between Wood Street and Chingford. The very southern end is served by the Elizabeth line at Manor Park.

Cultural Connections

Epping Forest has often been a setting for stories and has inspired poets, artists, and musicians for centuries. Many of these artists lived in or near Loughton. Loughton is also home to the East 15 Acting School.

Art in the Forest

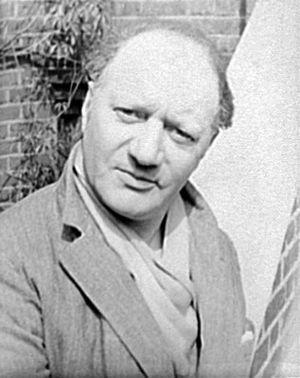

The famous sculptor Jacob Epstein lived on the edge of the forest in Loughton for 25 years. He once said he wanted his sculpture Visitation, now in the Tate Collection, to be placed overlooking the forest. In 1933, he showed 100 paintings of the forest and continued to paint it during the war. His painting Pool – Epping Forest, which shows Baldwins Hill Pond, was exhibited in 1945. Many of his forest paintings are in the Garman Ryan Collection at the New Art Gallery, Walsall.

Forest in Literature

Elizabethan poets like George Gascoigne and Thomas Lodge lived near the forest. The writer Lady Mary Wroth lived at Loughton Hall. Ben Jonson, known for his play The Alchemist, often visited the forest with George Chapman.

In Daniel Defoe's 1722 novel A Journal of the Plague Year, a group of Londoners try to escape the plague by staying in and around Epping Forest.

In the 1700s, Mary Wollstonecraft, a writer and philosopher, spent her first five years growing up in the forest.

In the 1800s, the poet Thomas Hood wrote The Epping Hunt in 1829, which was about the lively annual Easter Monday deer hunt for Londoners. In 1832, Hood and his wife moved to Lake House in Wanstead Park, which later became part of the forest. His 1838 novel Tylny Hall is set there. Charles Dickens' novel Barnaby Rudge starts with a description of the forest in 1775. Alfred, Lord Tennyson lived at Beech Hill House, High Beach, from 1837 to 1840, where he wrote parts of In Memoriam A.H.H.. He also stayed at a nearby asylum where he might have met poet John Clare. William Morris, an artist and writer, was born in Walthamstow in 1834 and spent his early years near the forest. Arthur Morrison, a writer, lived in Chingford, Loughton, and High Beach, and often used the forest in his books to contrast with the poverty he wrote about in East London. Rudyard Kipling and Stanley Baldwin spent a memorable holiday as boys in Loughton next to the forest, which they loved.

The poet Edward Thomas was stationed at a temporary army camp at High Beach in 1915. Despite the poor conditions, he enjoyed the forest and later moved to a cottage nearby. One of his last poems, Out in the dark, was written at High Beach in 1916, shortly before he died in France.

In the 1900s, several writers used the forest in their novels. These include R. Austin Freeman's The Jacob Street Mystery (1940), partly set at Loughton Camp. Dorothy L. Sayers' 1928 mystery Unnatural Death features the discovery of a body in Epping Forest. The horror writer James Herbert used Epping Forest as the setting for his novel Lair (1979), where giant rats attack humans. Herbert mentions an old legend about a white stag in the forest, which is said to be a sign of trouble. Natural historian and author Fred J Speakman lived at the Epping Forest Field Studies Centre and wrote several books about the area.

T. E. Lawrence (Lawrence of Arabia) owned land at Pole Hill, Chingford; this was added to the Forest in 1929.

Actor and playwright Ken Campbell (1941–2008) lived in Loughton, next to Epping Forest. His funeral was a woodland burial in the forest.

Music Inspired by the Forest

The song "The White Buck of Epping" by Sydney Carter (1957) tells the story of seeing and hunting a white buck in the forest.

A song on Genesis' 1973 album Selling England by the Pound is called "The Battle of Epping Forest." It refers to a real-life gang fight that happened in East London.

The inside cover of the progressive rock band Emerson, Lake & Palmer's album Trilogy shows many pictures of the band in the forest covered with autumn leaves.

The Wings album London Town includes the song "Famous Groupies" with lyrics about a lead guitarist who lived in Epping Forest.

Damon Albarn's song "Hollow Ponds" (2014) is based on his childhood memories of people swimming at Hollow Ponds in Epping Forest during the hot summer of 1976.

Forest in Movies

As of 2013, Epping Forest has been used as a filming location for fourteen movies. This includes the famous Black Knight scene in the 1975 British film Monty Python and the Holy Grail.

See also

In Spanish: Bosque de Epping para niños

In Spanish: Bosque de Epping para niños

- Edward Buxton, who helped save the forest for public use

- Epping Forest Keepers, who manage and care for the forest

- Fred J Speakman, a naturalist and author

- List of Sites of Special Scientific Interest in Greater London

- List of Sites of Special Scientific Interest in Essex

- Metropolitan Police Air Support Unit, based in the forest at Lippits Hill

- Stephen Pewsey, a historian

- Verderers of Epping Forest

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |