Blythburgh Priory facts for kids

Blythburgh Priory was a monastery in the village of Blythburgh in Suffolk, England. It was home to Augustinian canons, who were a type of religious community. The priory was dedicated to the Virgin Mary.

It was built in the early 1100s, making it one of the first Augustinian houses in England. At first, it was a smaller part of St Osyth's Priory in Essex. Even though it grew to have its own community, it always stayed quite small and connected to its parent monastery. Cardinal Wolsey planned to close it in the late 1520s, but it survived until the Dissolution in 1536.

The priory stood near the old parish church of Blythburgh, which is a famous landmark overlooking the River Blyth. However, the priory was a separate set of buildings. It had its own large Norman-style church and other stone buildings. It's important to remember that the priory church is now gone, but the parish church still stands. There might have been a link between these two sites even before the Norman Conquest.

For many years, the priory ruins were hidden by plants and forgotten. They were on private land, so people couldn't easily visit them. Recently, experts have been studying and preserving the ruins. They are still privately owned but are now looked after carefully. We know a lot about the priory, its supporters, and its lands from old records, especially a book called a Cartulary.

Interestingly, the priory is linked to a much older part of East Anglian history. Many believe it has a connection to King Anna of the East Angles. He was a Christian Anglo-Saxon king from the 600s who died defending his kingdom in battle around A.D. 654. An old book from the 1100s, called the Liber Eliensis, says that Blythburgh was thought to be the burial place of King Anna and his son Jurmin.

Contents

East Anglia's Early History (600s)

After the powerful East Anglian King Raedwald died around A.D. 624, his influence over other English rulers passed to Edwin of Northumbria. King Edwin became a Christian in 626. His marriage to Princess Æthelburh of Kent led to conflicts between his kingdom and the forces of King Cadwallon ap Cadfan of the Britons and King Penda of Mercia, who followed the god Woden.

Christianity truly began to grow in East Anglia under King Sigeberht. He was Raedwald's stepson and returned from exile in Gaul as a Christian. Sigeberht built schools and monasteries. He welcomed Felix as his bishop at Dommoc and the Irish monk Fursey at Cnobheresburg. Sigeberht later gave up his power and became a monk at Beodricesworth. King Penda invaded, and both Sigeberht and his co-ruler Ecgric were killed in battle.

King Anna, Raedwald's nephew, then became the ruler of East Anglia. The historian Bede, writing about 80 years later, described Anna as a good Christian king. He ruled through the 640s and even protected King Coenwalh of Wessex when Penda drove him out. Around 651, Penda attacked East Anglia again. Anna helped Fursey and his monks escape to Gaul, but Anna himself was exiled.

Anna later returned to his kingdom. In 654, Botolph, who might have been the chaplain to two of Anna's religious daughters, began building his monastery at Icanho. This place is thought to be Iken, near the river Alde.

Penda attacked again in a big battle at Bulcamp in 653 or 654. King Anna was killed, according to Bede. Old records like the Life of Etheldreda say this battle happened at Blythburgh. It also states that Anna died there with his son Jurmin and was buried nearby. Anna's saintly daughters, Seaxburga and Etheldreda, continued their religious work. After Penda's death in 654, Anna's brother Æthelwold brought a more peaceful time to East Anglia.

An Ancient Royal Estate

At the time of the Domesday Survey in 1086, Blythburgh was a royal estate. It had two churches that didn't own their own land. Because Blythburgh was a large estate near royal lands and a central part of its Hundred, it's believed there was an older, important church called a minster here before the Normans arrived.

It's likely that the Augustinian canons took over this old church when they founded the priory. The current Blythburgh parish church (Holy Trinity) and Walberswick church were probably the two smaller churches connected to it. This idea was strongly supported when parts of the priory church's south wall were dated to the 1000s or 1100s. This wall might have been part of an older parish church or even the minster church itself.

The Life of Saint Etheldreda, which is part of the Liber Eliensis, says that Anna and Jurmin were buried at Blythburgh. This belief might have existed before the Norman Conquest. The 1100s Liber also mentions that Jurmin's body was moved from Blythburgh to Bury St Edmunds as a holy relic. So, the story of Anna's last battle at Blythburgh was known early in medieval times.

The Priory's Medieval Beginnings

New Religious Communities

In the late 1000s and early 1100s, Benedictine monasteries were very large and powerful. They were often in cities, with grand buildings, influential abbots, and a lot of wealth. But some people wanted a simpler religious life. This led to the rise of canons regular, who lived in smaller, quieter communities. The Augustinian houses, like Blythburgh Priory, were founded on this idea.

The first house of canons regular in England was St Botolph's Priory in Colchester, which was reorganized before 1106. Around 1108, Holy Trinity Priory, Aldgate was founded in London with clergy from St Botolph's. Later, in 1121, the canons from Aldgate established St Osyth's Priory in Essex.

Blythburgh as a "Cell"

We don't know the exact date when canons arrived at Blythburgh. However, a charter from King Stephen in 1147 mentions two canons living there. Blythburgh probably remained a small "cell" (a dependent branch) of St Osyth's Priory. Later, between 1164 and 1170, King Henry II gave the abbot of St Osyth's the right to choose or remove the prior at Blythburgh.

Even though Blythburgh had to pay an annual tribute to St Osyth's, its prior and community could independently acquire lands. The historian Gardner noted that the priors of Blythburgh were always presented to the Bishops of Norwich by the local lords, who were the patrons of the priory.

Competing for Support

The priory's old records show that it didn't have one main supporter. There were many other religious houses nearby, like Sibton Abbey, Wangford Priory, and St. Olaves Priory. All these places were trying to attract money and support. In 1171, the leader of the choir at Blythburgh, Gilbert, was chosen to become the first prior of Butley Priory. This was a much larger Augustinian house for 36 canons.

The Local Lords

The ownership of Blythburgh can be traced back to King Stephen's grant to John de Chesney. After John's death, it passed to his brother William in 1157. Later, Margaret de Chesney inherited it. Her second husband, Robert fitzRoger, became lord of Blythburgh. He also founded a monastery at Langley, Norfolk. His descendant, Robert fitzRoger, confirmed all the previous grants to the priory in 1278. His son, John fitzRobert, was lord of Blythburgh from 1310 to 1332.

Priory's Income and Lands

The priory mainly earned money from rents in the Dunwich area. Records from 1198 and 1291 show that the priory received rents from several churches in Dunwich. King Edward II confirmed the priory's rights in 1319 and again in 1326. These records, along with the Cartulary, show that the priory owned many lands in and around Bulcamp, Blyford, Wenhaston, Holton St Peter, Henham, Sotherton, and Westhall.

Their lands also spread west towards Halesworth, including parishes like Heveningham and Huntingfield. To the north, they owned land in coastal areas like Covehithe and Frostenden. They also had holdings in the Waineford Hundred and even across the Waveney into Norfolk. To the south, their lands included the manor of Hinton Hall, which became a farm for the priory, and areas like Westleton and Yoxford.

The Priory Church

Only a few parts of the priory church, dedicated to the Blessed Virgin Mary, are still visible today. It seems that in the 900s or 1000s, there was already a building, probably a church, on this site. A section of its south wall, about 8.7 meters long and 3 meters high, still stands. It's made of flint and lime mortar, with decorative flint and Roman tiles. A corner stone is made of Quarr stone, which came from far away. Experts believe a similar wall stood about 8 meters to the north.

This older building was kept and used as the nave (the main part) of a new church built between about 1190 and 1220. The eastern end of the nave opened into a central tower area, supported by four large corner pillars. One of these pillars, made of rubble, still stands about 7.7 meters high. From this central area, a choir extended to the east, and large transepts (arms of the cross shape) extended north and south.

The south transept was 12 meters long. Only a small piece of the east wall of the north transept remains. Not much of the choir is left, but a trench suggests it was quite large. A single coffin was found buried in a special spot in the center of the choir, showing it was an important burial.

The stone covering on the western pillars shows a style that mixes Norman and Early English designs. These pillars had a curved front and slender columns at the corners. It's puzzling why the western side of the pillars was decorated, as they would have been against the old nave walls. It seems there were openings at ground level on both sides of the nave. This might mean they planned to demolish the old nave and build a new one with arched aisles, but this never happened.

On the north side of the nave, the ground was lower than the church floor. Steps led down from the transept's west doorway into a walkway about 3 meters wide. This walkway went along the outside of the nave and the transept's west wall. This suggests that the priory's cloister (a covered walkway, usually in a square, where monks would walk) was on the north side of the church, which is unusual. The south wall of the nave has no windows, suggesting there were other buildings outside it. The long and complex building history of this church is more than you might expect for a small priory with only a few canons.

The Priory's End

When the monasteries were dissolved, an inventory of Blythburgh Priory's goods was made on August 20, 1536. The priory's site, including its church, steeple, churchyard, lands, and manors, was granted to Walter Wadelond in 1536. Later, in 1538, it was given to Sir Arthur Hopton. The grant included the priory's lands, the churches of Blythburgh, Thoryngton, Bramefeld, and Wenaston, and the chapel of Walberswick.

The Hopton family had a long history in Blythburgh. Their ancestor, Sir Robert de Swyllington, owned lands here. The Hoptons became very wealthy landowners. John Hopton made his home at Westwood Lodge in Blythburgh and developed the quay at Walberswick. He also bought manors at Yoxford and Cockfield Hall. John Hopton died in 1478. In 1451, he was allowed to create the "Hopton Chaunterye" in Holy Trinity Church, Blythburgh. This is thought to be the Hopton chapel at the north-east corner of Blythburgh church, which has a special tomb.

The Hoptons were important supporters of the Blythburgh churches before the Reformation. Sir Arthur Hopton (1488-1555) was the grandson of Sir William Hopton, who was a treasurer to King Richard III. Sir Arthur's son, Sir Owen Hopton, was the Lieutenant of the Tower of London for Queen Elizabeth I. In 1577, Blythburgh experienced the famous event of the Black Hellhound appearing in Holy Trinity church. Later, in 1597, Sir Owen's son, the younger Arthur Hopton (died 1607), sold some of his estates, but not the former priory lands. This led to a long lawsuit.

Rediscovering the Ancient Past

The connection to King Anna was never completely forgotten. John Leland, a historian from the 1500s, wrote about the battle and burial: "King Anna was killed by Penda... and he is buried in the place which is called Blidesburg. There also his son Jurmin was buried..." Leland's words suggest people believed Anna's body was still there.

John Weever, in his book Ancient Funerall Monuments (1631), also mentioned that King Anna and his son Ferminus were buried at Blythburgh after being killed in battle by King Penda. Since the mid-1700s, a medieval tomb in the parish church was often pointed out as Anna's tomb.

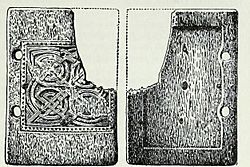

A very interesting discovery was made at the priory site many years ago. It was a bone plaque carved with Anglo-Saxon patterns. It was one part of a folding writing-tablet that held wax for writing. Inside, there were traces of runic inscriptions (old letters). This showed that educated people lived at Blythburgh during the middle Anglo-Saxon period. This plaque is now in the British Museum.

In 1970, pieces of "Ipswich Ware" pottery were found at the site. This special pottery was made in Ipswich between the late 600s and mid-800s. Finding it showed that people lived in Blythburgh during the middle Anglo-Saxon period. In 2008, the TV show Time Team did an archaeological dig. They found burials from the mid-600s in the area of the priory church. This proved that the medieval priory and the buildings before it were on a site that had been used for burials since King Anna's time.

Investigating the Medieval Ruins Again

"Considerable remains of this College now appear a little North-East of the church," wrote John Kirby in 1735. His map showed the priory with a long wall and round arches. An illustration from 1772 by Francis Grose showed a large, tall mass of stone with round arches. Taylor, in his 1821 book, noted that "Some portion of the priory is yet standing about 150 yards to the north-east of the parochial church." He also said that a lot of stone from the ruins was used to build the nearby bridge and dam around 1785.

Hamlet Watling (1818-1908) wrote about the ruins in the 1890s. He said that a large part of them was taken away around 1850 to repair roads. During excavations, old coins, keys, and decorated tiles were found, but they were unfortunately sold to private collectors. Watling also mentioned that several human skeletons were found scattered on the church floor. He thought this might mean there was a struggle when the priory was closed.

After the Time Team investigation in 2008, more detailed and systematic studies began in 2009. These were led by Stuart Boulter and Bob Carr from the Suffolk County Council Archaeological Service, working with English Heritage and the site owners. These efforts have helped experts understand the layout of the large priory church, with its central crossing, transepts, and the cloister on the north side. These works have answered many questions and allowed the ruins to be preserved. The site owners have even created a website to share the story of rediscovering and investigating these important remains.

Images for kids

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |