John Leland (antiquary) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

John Leland

|

|

|---|---|

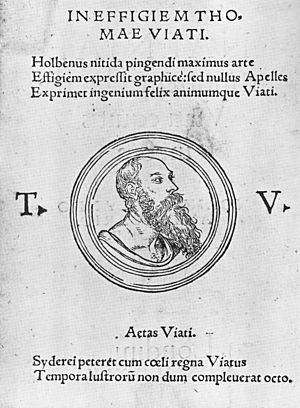

Line engraving by Charles Grignion the Elder (1772), purportedly taken from a bust of John Leland at All Souls College, Oxford. Sculptor Louis François Roubiliac (d. 1762) probably created the original bust.

|

|

| Born | 13 September c. 1503 London

|

| Died | 18 April 1552 |

| Resting place | parish church of St Michael-le-Querne, London |

| Monuments | destroyed by fire in 1666 |

| Nationality | English |

| Other names | John Leyland, Layland |

| Education | St Paul's School (London) Christ's College, Cambridge All Souls College, Oxford |

| Known for | Latin poetry, antiquarianism |

|

Notable work

|

include Cygnea cantio (1545) |

| Relatives | an elder brother called John |

John Leland (born September 13, c. 1503 – died April 18, 1552) was an English poet and antiquary. An antiquary is someone who studies old things.

Many people call Leland "the father of English local history". He also helped create the idea of studying history by county. His famous book, Itinerary, was a key source for later historians. It gave them lots of information about England and Wales.

Contents

- John Leland's Early Life and School

- Working for the King

- Exploring Libraries: 1533–1536

- Leland's Journeys: The Itineraries (around 1538–1543)

- The "New Year's Gift" (around 1544)

- Leland and Archaeology

- Leland and King Arthur

- Leland's Final Years and Death

- Leland's Collections and Notebooks

- The Leland Trail

- Leland's Writings

- Images for kids

- See also

John Leland's Early Life and School

Most of what we know about John Leland comes from his own writings. He was born in London on September 13, probably around 1503. He had an older brother, also named John.

Leland lost both his parents when he was young. He and his brother were raised by Thomas Myles. John went to St Paul's School in London. His headmaster was William Lily. Here, he met people who would later help him, like William Paget.

College Days and Travel

After St Paul's, Leland went to Christ's College, Cambridge. He earned his degree in 1522. While studying there, he was briefly put in prison. He had accused a knight of working with Richard de la Pole.

Later, Leland worked for Thomas Howard, 2nd Duke of Norfolk. He taught the Duke's son, also named Thomas. When the Duke died in 1524, the king sent Leland to Oxford. He became a fellow at All Souls College, Oxford. However, Leland felt that Oxford's teaching of classical studies was too old-fashioned.

Between 1526 and 1528, Leland studied in Paris. He met many other students from England and Germany. He wanted to study in Italy too, but it never happened. In Paris, Leland improved his Latin poetry skills. He also met famous scholars like Guillaume Budé. One important teacher for Leland was François Dubois. He greatly influenced Leland's interest in poetry and old things. While in France, Leland stayed in touch with his friends in England. This included Thomas Wolsey, who made him a rector in Laverstoke, Hampshire.

Working for the King

By 1529, Leland was back in England. When Cardinal Wolsey lost the king's favor, Leland found a new supporter. This was Thomas Cromwell. This friendship helped Leland's career.

King Henry VIII made Leland one of his chaplains. He also gave him a church job in Peuplingues, near Calais. In 1533, Leland got permission to hold four church jobs. He had to become a subdeacon within two years and a priest within seven. In 1535, he became a prebendary at Wilton Abbey in Wiltshire. He also received two more church jobs nearby.

Leland and Nicholas Udall wrote poems for Anne Boleyn's arrival in London in 1533. This was for her coronation as queen. Their shared supporter was likely Thomas, Duke of Norfolk. They worked together again in 1533 and 1534. Leland wrote poems for Udall's book, Floures for Latine Spekynge.

Exploring Libraries: 1533–1536

In 1533, King Henry VIII gave Leland a special task. He received a "moste gratius commission" (a royal order). This allowed him to visit and use the libraries of all religious houses in England.

Leland spent the next few years traveling. He visited many monasteries just before they were closed down. He made lists of important or unusual books in their libraries. Around 1535, he met John Bale, another scholar who admired his work.

Saving Books

In 1536, after many monasteries were ordered to close, Leland worried about the books. He saw that many valuable books were being lost or destroyed. He wrote to Thomas Cromwell asking for help to save them.

Leland complained that:

The Germans perceive our desidiousness, and do send daily young scholars hither that spoileth [books], and cutteth them out of libraries, returning home and putting them abroad as monuments of their own country.

This means that German scholars were coming to England. They were taking books from libraries and claiming them as their own.

During the 1530s and 1540s, the royal library was reorganized. Hundreds of books from monasteries were added to it. Leland described how Henry's palaces were changed for this purpose. It's not clear exactly what Leland's role was in moving these books. He called himself an antiquarius, meaning a scholar of old things. He compiled lists of important books and tried to make sure they were saved.

Leland's Journeys: The Itineraries (around 1538–1543)

Even after the Dissolution of the Monasteries, Leland kept looking for books. He got permission to use the library of the closed monastery of Bury St Edmunds. But his travels and the old descriptions he found sparked new interests.

Around 1538, Leland started focusing on the geography and old sites of England and Wales. He began a series of journeys that lasted six years. He traveled through Wales, probably in the summer of 1538. He then made five major trips across England between 1539 and 1543.

What Leland Saw and Wrote

His trip in 1542 is the only one with a firm date. It took him to the West Country. He also toured the north-west, going through Welsh marches to Cheshire, Lancashire, and Cumberland. Other trips took him to the west Midlands, the north-east (reaching Yorkshire and County Durham), and the Bristol area. He likely explored the south-east on shorter trips. He is not known to have visited East Anglia.

Leland kept notebooks during his travels. He wrote down what he saw, and information from books and people. This collection of notes is now known as his 'Itinerary'.

The Itinerary is made up of rough notes and early drafts. Leland never planned to publish it as it is. He made the most progress on his notes for Kent. He wrote, "Let this be the firste chapitre of the booke". He added, "The King hymself was borne yn Kent. Kent is the key of al Englande."

Even though Leland's Itinerary notes were not published until the 1700s, they were very important. They provided a lot of information for William Camden's Britannia (first published in 1586) and many other historical works.

The "New Year's Gift" (around 1544)

In the mid-1540s, Leland wrote a letter to Henry VIII. In it, he described what he had done and what he planned to do. This letter was later published by John Bale in 1549. It was called The laboryouse journey & serche of Johan Leylande for Englandes antiquitees. People often called it a "New Year's gift" to the King. However, it was likely written in late 1543 or early 1544.

In the letter, Leland told the king about his efforts to save books. He also described how much he had traveled:

I have so travelid yn yowr dominions booth by the se costes and the midle partes, sparing nother labor nor costes, by the space of these vi. yeres paste, that there is almoste nother cape, nor bay, haven, creke or peere, river or confluence of rivers, breches, waschis, lakes, meres, fenny waters, montaynes, valleis, mores, hethes, forestes, wooddes, cities, burges, castelles, principale manor placis, monasteries, and colleges, but I have seene them; and notid yn so doing a hole worlde of thinges very memorable.

This means he traveled all over England and Wales. He saw almost every type of place, from coasts to mountains. He noted many memorable things.

Leland also shared his plans for using all this information. He had four main projects in mind:

- De uiris illustribus: A book about famous British writers, organized by time period.

- A detailed map of England on a silver table for the King. It would come with a written description and a guide to old place-names.

- A history of England and Wales, called De Antiquitate Britannica. This book would have about 50 parts, one for each county. It would also have six parts about Britain's islands.

- De nobilitate Britannica: A list of royalty, nobles, and leaders, organized by time.

Only De uiris illustribus was mostly finished. The other projects never happened. Some people, like Polydore Vergil, thought Leland promised more than he could do.

Leland and Archaeology

Leland was very interested in recording the history of England and Wales. He looked for clues in the landscape. He noted all kinds of old remains, like megaliths (large stones), hillforts, and Roman and medieval ruins.

He found several Roman inscriptions. He couldn't read most of them. He complained that one was made of "letters for whole words, and 2. or 3. letters conveid in one". He often reported finding old coins. For example, at Richborough, Kent, he said more Roman money was found there than anywhere else in England. He also carefully studied building materials.

Smart Observations

Leland was often able to make clever guesses from what he saw. In Lincoln, he identified three stages of city growth. First, a British settlement at the top of the hill. Then, the Saxon and medieval town further south. Finally, a newer area by the river. He correctly guessed that Ripon Minster was built after the Norman Conquest. He also correctly identified "Briton brykes" (which were actually Roman bricks) at several sites.

Usually, he just recorded what he saw on the surface. But once, he did a bit of digging. At the hillfort at Burrough Hill, Leicestershire, he pulled some stones from a gateway. He wanted to see if it had been walled. The stones were held together with mortar, which told him it had been. This account in Leland's Itinerary might be the first ever archaeological field report!

Leland and King Arthur

Leland was a strong patriot. He truly believed that King Arthur was a real historical figure. So, he was upset when the Italian scholar Polydore Vergil questioned parts of the Arthurian legend. Vergil published his Anglica Historia in 1534.

Leland's first response was a short, unpublished work around 1536. He then wrote a longer book, Assertio inclytissimi Arturii regis Britannia (1544). In both books, Leland used many sources to defend Arthur's existence. He looked at old stories, word origins, archaeological finds, and oral traditions. Even though his main belief was wrong, his work saved a lot of information about the Arthurian legend that might have been lost.

Arthur's Tomb and Camelot

Leland's notes are very helpful for understanding Arthur's "tomb monument" at Glastonbury Abbey. This tomb is now lost. He probably also drew the lead cross that said the grave belonged to Arthur. This drawing was later published in 1607.

On his 1542 journey, Leland was the first to record a local story. This story said that Cadbury Castle in Somerset was Arthur's Camelot. This idea might have come from nearby villages called Queen Camel and West Camel. Leland wrote:

At the very south ende of the chirch of South-Cadbyri standeth Camallate, sumtyme a famose toun or castelle, apon a very torre or hille, wunderfully enstregnthenid of nature.... The people can telle nothing ther but that they have hard say that Arture much resortid to Camalat.

This means people in the area said Arthur often visited Camalat.

Leland's Final Years and Death

In 1542, King Henry gave Leland a valuable church job in Great Haseley, Oxfordshire. The next year, he was given another job at King's College (now Christ Church, Oxford). Around the same time, he got a job at Sarum church. He had a good income and plenty of free time to follow his interests.

Leland moved to his house in London, near Cheapside. He planned to work on his many projects there. However, in February 1547, around the time King Henry died, Leland "fell besides his wits." He was certified insane in March 1550. John Leland died on April 18, 1552, at about 48 years old. He was still mentally ill.

Leland was buried in the church of St Michael-le-Querne, near his home. But the church was destroyed in the Great Fire of London in 1666 and never rebuilt. So, Leland's tomb is now lost.

Leland's Collections and Notebooks

After Leland's death, or when he became ill, King Edward VI arranged for his library to be looked after. Many medieval manuscripts were given to Sir John Cheke. John Bale looked at some of these books then.

Cheke lost favor when Queen Mary became queen. He left for Europe in 1554. After that, and after Cheke died in 1557, Leland's library was scattered. Collectors like Sir William Cecil and John Dee bought some of the books.

Where the Notebooks Ended Up

Leland's own handwritten notebooks were passed to Cheke's son, Henry. In 1576, John Stow borrowed and copied them. This allowed Leland's notes to be shared among scholars. Scholars like William Camden and William Harrison got to see them through Stow.

The original notebooks went from Henry Cheke to Humphrey Purefoy. After Purefoy died in 1598, his son Thomas divided many of them. He gave some to his cousins, John Hales and William Burton. Burton later got back several items given to Hales. In 1632 and 1642–43, Burton gave most of the collection to the Bodleian Library in Oxford. These important volumes are still there today.

The Leland Trail

The Leland Trail is a 28-mile (45 km) footpath. It follows the path John Leland took through South Somerset. He walked this route between 1535 and 1543 while studying old sites. The Leland Trail starts at King Alfred's Tower on the Wiltshire/Somerset border. It ends at Ham Hill Country Park.

Leland's Writings

John Leland wrote many important works, both poetry and prose. His writings are a valuable source of information. They tell us about the local history and geography of England. They also help us understand literary history, archaeology, and how people lived and worked in his time.

Latin Poetry

- Naeniae in mortem Thomæ Viati, equitis incomparabilis (1542): A poem praising Sir Thomas Wyatt after his death.

- Genethliacon illustrissimi Eaduerdi principis Cambriae (1543): A poem about the birth of Prince Edward (who became Edward VI) in 1537. It focuses on Wales, Cornwall, and Cheshire.

- Cygnea cantio (1545): A long "river poem" that praises Henry VIII. It tells the story through the voice of a swan swimming down the Thames.

Antiquarian Prose Writings

- Assertio inclytissimi Arturii regis Britanniae (1544): Leland's book defending the historical truth of King Arthur.

- The "New Year's Gift" (c. 1544): A letter to Henry VIII.

- De uiris illustribus (written c. 1535–36 and c. 1543–46): A dictionary of famous British authors. Leland did not finish this work.

- The "Collectanea" (compiled 1533–36): Leland's many notes and copies from his visits to monastery libraries. These include most of his lists of books.

- Itinerary notebooks (compiled c. 1538–43): Leland's notes about places and geography.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: John Leland para niños

In Spanish: John Leland para niños

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |