A. K. Chesterton facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

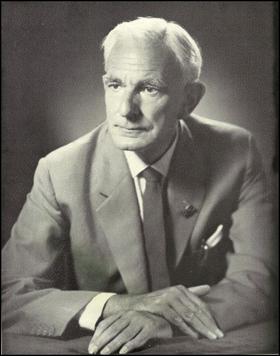

A. K. Chesterton

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Arthur Kenneth Chesterton

1 May 1899 Krugersdorp, South African Republic |

| Died | 16 August 1973 (aged 74) London, United Kingdom |

| Political party |

|

| Relations | G. K. Chesterton (first cousin, once removed) Cecil Chesterton (first cousin, once removed) |

Arthur Kenneth Chesterton MC (born May 1, 1899 – died August 16, 1973) was a British journalist and political activist. He was involved with several political groups throughout his life. From 1933 to 1938, he was a member of the British Union of Fascists (BUF).

After leaving the BUF, Chesterton started the League of Empire Loyalists in 1954. This group later joined with another party in 1967 to form the National Front. He also founded and edited a magazine called Candour, which began in 1954.

Contents

About Arthur Kenneth Chesterton

His Early Life and Schooling

Arthur Kenneth Chesterton was born on May 1, 1899, in Krugersdorp, which was then part of the South African Republic. His father worked at a gold mine. Arthur was a distant cousin of the famous writer G. K. Chesterton. He looked up to his cousin Cecil Chesterton, who was a journalist.

When the Second Boer War started in 1899, young Arthur and his mother moved to England for safety. Sadly, his father died soon after. In 1902, Arthur returned to South Africa with his mother. When he was 12, he was sent back to England to live with his grandfather. He went to schools like Dulwich College and Berkhamsted School.

Serving in World War I

In 1915, at age 16, Chesterton convinced his parents to let him join the army in South Africa. He was too young, so he changed his age to enlist in the 5th South African Light Infantry. He fought against German forces in East Africa. During a march, he became very sick and was left behind, but two African porters saved him.

After getting better, Chesterton, now 17, joined the army again. He went to Ireland to train as an officer. In 1918, he became a second lieutenant and served on the Western Front in Europe. He was awarded the Military Cross for his brave actions during a battle in France in September 1918.

After the war, Chesterton suffered from health problems like malaria and breathing issues from a gas attack. He also had bad dreams about the war.

His Career as a Journalist

Around 1919, Chesterton moved back to South Africa and started working as a journalist for The Johannesburg Star. In 1924, he returned to England. He became known as a critic of Shakespeare's plays. He worked as a journalist and public relations officer at the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre.

In 1929, Chesterton met Doris Terry, a schoolteacher, and they married in 1933. Doris had different political views than him. From 1929 to 1931, he worked for the Torquay Times. In 1933, he joined the British Union of Fascists (BUF).

Joining the British Union of Fascists

After joining the BUF, Chesterton quickly rose through the ranks. He became an officer in charge of different areas and later the Director of Press Propaganda. He also became editor of the BUF's newspaper, The Blackshirt. In this role, he wrote articles that promoted strong anti-Jewish views.

He also wrote a book about the BUF leader, Oswald Mosley, called Oswald Mosley: Portrait of a Leader (1937). This book praised Mosley greatly.

World War II and Beyond

By the late 1930s, Chesterton became unhappy with Mosley and the BUF. He left the party in 1938. He then joined other groups that were against war with Germany. In 1939, he started his own group called British Vigil. He also became involved with the Right Club, a group that aimed to unite right-wing organizations in Britain.

When World War II began in 1939, Chesterton rejoined the British Army. He served in Kenya and Somaliland. After the war, he continued his work as a journalist for various newspapers. He also became deputy editor of Truth magazine.

Post-War Activities

In 1945, Chesterton helped create a group called the National Front. This group wanted to protect the British Empire and Christian traditions. From 1950 to 1958, he wrote articles for The Journal of the Royal United Services Institution.

He also worked for Lord Beaverbrook, a newspaper owner, and helped him write his autobiography. In 1953, Chesterton started his own magazine, Candour, which is still published today.

In 1954, Chesterton founded the League of Empire Loyalists (LEL). This group was known for interrupting political meetings to protest and chant slogans like "Save the Empire." Many future far-right leaders were part of this group.

The 1960s and Later Life

In 1965, Chesterton published a book called The New Unhappy Lords. This book explored his ideas about powerful groups secretly controlling the world. He believed these groups were working against the British Empire. The book sold many copies.

In 1967, Chesterton founded a second National Front party. He was its first chairman. This new party brought together his LEL group and another party. He tried to keep out very extreme members at first, but later welcomed some.

Towards the end of his life, Chesterton became very ill with a lung disease he got from the gas attack in World War I. He spent some time in South Africa. In 1970, he resigned from the National Front due to health and leadership challenges. He continued to edit Candour magazine until he died on August 16, 1973, at the age of 74.

His Political Views

Historians say Chesterton's views were a mix of ideas, including strong beliefs about race and a focus on conspiracy theories. He believed in protecting the British monarchy and culture.

After World War II, Chesterton said he no longer supported fascism. He also changed how he talked about his anti-Jewish views, making them less harsh. However, Jewish people still remained central to his conspiracy theories. For example, he believed The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, a fake document, was a good analysis of society's weaknesses. Later in life, he thought that using very strong anti-Jewish language was harmful to his political movement.

His Influence

Arthur Kenneth Chesterton had a big impact on other political figures. John Tyndall, who later started the British National Party (BNP), said that Chesterton taught him a lot about politics. Martin Webster, another important figure in the National Front, also said Chesterton's book The New Unhappy Lords greatly influenced him. Chesterton was also friends with Revilo P. Oliver, and they wrote to each other often.

His Published Works

Chesterton's writings have been republished by the A. K. Chesterton Trust. He also wrote a play under the pen name Caius Marcius Coriolanus.

Books

- Adventures in Dramatic Appreciation (1931)

- Brave Enterprise: A History of the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon (1934)

- Creed of a Fascist Revolutionary (1935)

- Oswald Mosley: Portrait of a Leader (1937)

- Why I Left Mosley (1938)

- No Shelter for Morrison (1945) - published as Caius Marcius Coriolanus

- The Menace of the Money Power: An Analysis of World Government by Finance (1946)

- Alternative for Britain (1946)

- Juma the Great (1947)

- The Importance of Being Oswald (1947)

- The Tragedy of Anti-Semitism, with Joseph Leftwich (1948)

- Sound the Alarm! A Warning to the British Nations (1954)

- Stand By The Empire (1954)

- The Menace of World Government & Britain's Graveyard (1957)

- Tomorrow. A Plan for the British Future (1961)

- The New Unhappy Lords: An Exposure of Power Politics (1965)

- Common Market ... (1971)

- B.B.C.: A National Menace (1972)

- Facing the Abyss (published after his death; 1976)

- Fascism and the Press (published after his death; 2013)

Articles

- British Union Quarterly, Vol. 1, No. 2, April/June 1937, pp. 45–54.

Pamphlets

- Not Guilty: An Account of the Historic Race Relations Trial at Lewes Assizes in March 1968 (1968)

Plays

- Leopard Valley: A Play in Three Acts (1943)

See also

- Candour – a British magazine with far-right views