Electoral system facts for kids

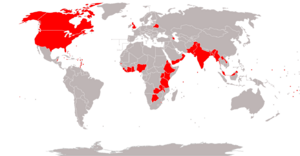

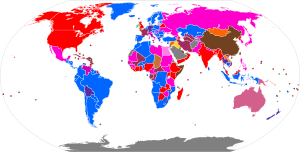

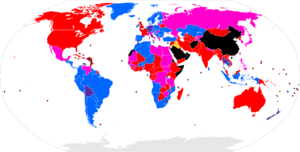

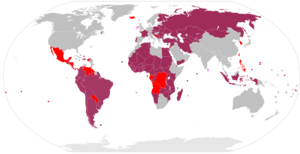

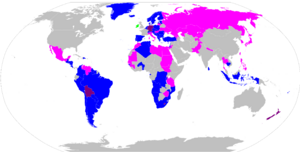

Majoritarian system, single-winner districts

First-past-the-post voting (single-member plurality) Two-round system (runoff) Instant-runoff voting (alternative vote) Majoritarian system, multi-winner districts

Plurality-at-large voting (block voting) General ticket (party block voting) Semi-proportional system

Limited voting or cumulative voting Single non-transferable vote Modified Borda count

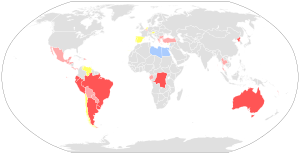

Proportional system

Party-list proportional representation Single transferable vote

Mixed system

Mixed-member proportional representation

Mixed-member majoritarian representation

Majority bonus/jackpot system

Other No election Varies by state No information

An electoral system or voting system is a set of rules for how elections work. These rules decide when elections happen and who can vote. They also cover who can run for office and how votes are counted. These systems are used in politics to choose governments. They are also used in businesses and other groups to elect leaders.

Some systems pick one winner for a job like president. Others choose many winners, such as members of a parliament. Countries often divide into areas called constituencies. Each area might elect one or more people. Voters can choose individual people or a list of people from a political party. There are many types of electoral systems. Some common ones are first-past-the-post voting, two-round systems, and proportional representation. Some systems, called mixed systems, try to combine different ideas.

Contents

Types of Electoral Systems

Plurality Systems

In a plurality voting system, the person or people with the most votes win. They do not need to get more than half of the votes. If only one position is being filled, it is called first-past-the-post. This system is used in many countries, especially those with ties to Britain or America. It is also common for choosing presidents.

When many positions are open, like in multi-member areas, it is called block voting. In one type, voters have as many votes as there are seats. They can vote for any person, no matter their party. This is used in a few countries. A variation is limited voting, where voters have fewer votes than there are seats. Another is single non-transferable vote (SNTV). Here, voters pick only one person in a multi-member area. The people with the most votes win.

Another type of block voting is party block voting. Voters can only choose multiple people from one party. The party with the most votes wins all the positions. This system is used in some countries as part of mixed systems.

Majority Systems

In a majority voting system, a person must get more than half of the votes to win. This can happen in one election or over several rounds. These systems are mostly used for single positions.

One way to get a majority in a single election is instant-runoff voting (IRV). Voters rank candidates in order of their preference. If no one gets a majority at first, the votes from the lowest-ranked person are moved to the voters' second choices. This continues until someone gets over 50% of the votes. This system is used in countries like Australia.

The other main majority system is the two-round system. This is very common for presidential elections worldwide. If no one gets a majority in the first round, a second round is held. Usually, only the top two candidates from the first round compete in the second. Sometimes, more than two candidates can be in the second round. In these cases, the winner is simply the one with the most votes. Some countries have modified versions of this system.

Proportional Systems

Proportional representation is the most common way to elect national parliaments. Over eighty countries use different forms of this system.

Party-list proportional representation is the most common type. Voters choose a list of people put forward by a party. In some systems, called closed list, voters cannot change the order of people on the list. In open list systems, voters can influence the order. In some countries, votes are counted nationally. This means seats are given to parties based on their total national votes. More often, countries use several multi-member areas. This helps with local representation.

There are different ways to give out seats in proportional systems. Some use a "highest average" method. Here, votes for each party are divided by a series of numbers. This helps decide how many seats each party gets. Other systems use a "largest remainder" method. Here, parties' votes are divided by a quota. Any leftover seats are given to parties with the largest fractions of votes remaining.

Single transferable vote (STV) is another proportional system. Voters rank candidates in multi-member areas instead of choosing a party list. To win, candidates must reach a certain number of votes, called a quota. If a candidate gets enough votes in the first count, they win. Extra votes from winners and votes from losing candidates are then moved to other choices. This continues until all seats are filled.

Mixed Systems

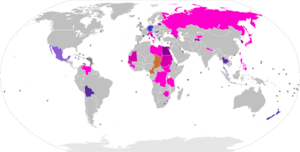

Non-compensatory Parallel voting (superposition): list-PR + FPTP Parallel voting: list-PR + PBV Parallel voting: list-PR + TRS Conditional: list-PR or PBV (above 50%) Majority bonus system (fusion): list-PR + PBV

Compensatory Partially compensatory: list-PR + FPTP Additional member system: list-PR + FPTP Mixed-member proportional: list-PR + FPTP Majority jackpot (fusion): list-PR + PBV

Many countries use mixed systems to elect their lawmakers. These include parallel voting and mixed-member proportional representation.

In parallel voting systems, lawmakers are chosen in two ways. Some are elected by simple majority or plurality votes in single areas. Others are chosen using proportional representation. The results from the single-area votes do not affect the proportional vote results.

In compensatory mixed-member representation, the proportional vote results are adjusted. This helps balance the seats won in the single-area votes. In mixed-member proportional systems, parties get a number of seats that matches their overall vote share.

Some systems give a majority bonus to a party. This helps one party or group get a clear majority of seats in the parliament. For example, in San Marino, the winning party in the second round is guaranteed a certain number of seats.

Primary Elections

Primary elections are a part of some electoral systems. They help political parties choose their candidates before the main election. This helps make sure only one candidate from each party runs. In some countries, like Argentina, primary elections are a formal part of the election process. If a party gets too few votes in the primary, they cannot run in the main election.

Indirect Elections

Some elections use an indirect system. This means there might not be a direct public vote. Or, the public vote is only one step. The final vote is often taken by an electoral college. For example, in the United States, people vote in each state to choose members for the electoral college. These members then elect the President. Sometimes, a candidate can win the most votes nationwide but still lose the electoral college vote. This happened in the US in 2000 and 2016.

Rules and Regulations

Electoral systems also have wider rules and regulations. These are usually found in a country's constitution or electoral law. These rules cover how people can become candidates and how voters register. They also decide where people vote and if they can vote online or by mail. Other rules cover the type of ballots used and how votes are counted.

Electoral rules also set limits on who can vote and who can run. Most countries have universal suffrage, meaning most adults can vote. But there are differences in the age people can vote. People might not be allowed to vote for reasons like being in prison. Similar limits are placed on candidates. In many places, the age limit for candidates is higher than the voting age. Some countries have compulsory voting, meaning it is required by law to vote.

In systems with constituencies, the boundaries of these areas are important. Where these lines are drawn can greatly affect election results. Political parties might try to draw boundaries to help their side win. This is called gerrymandering.

Some countries require a minimum number of voters to participate for an election to be valid. If not enough people vote, the election might have to be held again.

Reserved seats are used in many countries. These seats ensure that groups like ethnic minorities, women, or young people have representation. These seats are separate from general seats. They might be elected differently or given to parties based on election results.

History of Voting

Early Democracy

Voting has been part of democracy since ancient Greece, around 6th century BCE. However, in Athens, voting was not seen as the most democratic way to choose officials. They thought elections favored rich or famous people. Instead, they preferred open assemblies or choosing people by lot.

In ancient Rome, people voted by dividing into groups. But this system could be unfair. So, later laws introduced secret ballots using wax-covered wooden slips. Usually, a simple majority of votes was enough to pass something.

One exception to simple voting was in Venice in the 13th century. They used a very complex system to elect their leader, the Doge. It involved many rounds of drawing lots and voting. This system was hard to trick and helped make sure the winner represented different groups. It was used for over 500 years.

New Systems Develop

In the 18th century, new voting ideas emerged. Jean-Charles de Borda suggested the Borda count method. The Marquis de Condorcet proposed comparing candidates in pairs. Later, it was found that a philosopher named Ramon Llull had thought of similar ideas much earlier.

The United States Constitution needed a way to divide seats in the House of Representatives fairly among states. This led to different methods of "apportionment." Some of these methods were later rediscovered in Europe for proportional representation. For example, "Jefferson's method" is like the D'Hondt method.

The single transferable vote (STV) method was developed in Denmark and the United Kingdom in the mid-1800s. It was first used in elections in Denmark and later in Tasmania. Party-list proportional representation began to be used in European parliaments in the early 1900s. Since then, proportional systems have become common in most democratic countries.

Recent Changes

In the late 1800s, people started looking at single-winner voting methods again. William Robert Ware suggested applying STV to single-winner elections, which led to instant-runoff voting (IRV). Mathematicians also revisited Condorcet's ideas.

Ranked voting systems eventually gained enough support for government elections. Australia adopted IRV in 1893 and still uses it today. In the United States, some cities began using IRV in the early 1900s.

In recent times, there has been a push for electoral reform. People have proposed changing traditional voting methods. New Zealand adopted mixed-member proportional representation in 1993. After problems in the 2000 US presidential election, some US cities adopted IRV. However, not all attempts to change systems have been successful. Referendums in Canada and the UK to adopt new systems failed.

Comparison of Electoral Systems

We can compare electoral systems in different ways. How people feel about a system often depends on how it affects groups they support. This can make it hard to compare systems fairly.

One way is to use math to define criteria. A system either meets the criteria or it does not. This gives clear results, but it might not show how well the system works in real life.

Another way is to look at how often a system meets ideal goals in many pretend elections. This gives practical results. But how the pretend elections are set up can affect the outcome.

A third way is to look at practical things like how many people vote or how easy it is to count votes. Experts can then judge each method. This way can show things the other ways miss. But the definitions and judgments can be subjective.

Experts have studied how electoral systems affect voters and political parties. They also look at how systems affect political stability.

According to a 2006 survey of experts, their favorite electoral systems were:

- Mixed member proportional

- Single transferable vote

- Open list proportional

- Alternative vote

- Closed list proportional

- Single member plurality

- Runoffs

- Mixed member majoritarian

- Single non-transferable vote

See also

In Spanish: Sistema electoral para niños

In Spanish: Sistema electoral para niños

- Comparison of electoral systems

- Election

- List of electoral systems by country

- Matrix vote

- Spoiler effect

- Psephology

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |