Instant-runoff voting facts for kids

Instant-runoff voting (IRV) is a special way to vote in elections. It's used when there are more than two people running for one job, like a mayor or a president. Instead of just picking one person, you get to rank the candidates in the order you like them best.

In the United States, this system is often called ranked-choice voting (RCV). In Australia, it's known as preferential voting. In the United Kingdom, it's usually called the alternative vote (AV). These names can sometimes be a bit confusing!

When you vote with IRV, you put a '1' next to your favorite candidate, a '2' next to your second favorite, and so on.

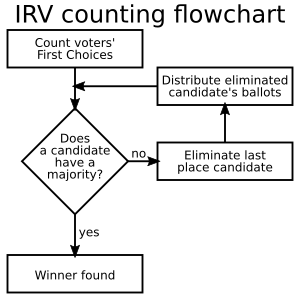

Here's how the votes are counted:

- First, they count everyone's number '1' choices.

- If someone gets more than half of these first-choice votes, they win right away!

- If no one gets more than half, the candidate with the fewest first-choice votes is eliminated.

- Then, the votes from the eliminated candidate are given to the voter's next choice.

- This process keeps going until one candidate has more than half of the votes. That person becomes the winner!

IRV is used in many places around the world. For example, it helps elect members of the Australian House of Representatives. It's also used to choose the President of Ireland and the President of India. Many political parties use it to pick their leaders too.

Contents

How Elections Work with IRV

The Counting Process

When you vote in an IRV election, you rank the candidates. You might put a '1' for your top choice, a '2' for your second, and so on. You can usually rank as many or as few candidates as you want. But sometimes, you might need to rank everyone for your vote to count.

Here are the steps for counting IRV votes:

- The candidate with the fewest first-place votes is removed.

- If only one candidate is left, they win!

- If not, the process repeats: the candidate with the fewest votes is removed again.

If there's a tie for last place, there are special rules to decide who gets eliminated. When a candidate is eliminated, their votes are given to the next preferred candidate on each ballot. This continues until one candidate has more than half of the votes that are still active. If all your ranked candidates are eliminated, your ballot becomes "inactive."

How Candidates Appear on the Ballot

Candidates are usually listed on the ballot paper in alphabetical order or in a random order. Sometimes, they are grouped by their political party. Another way is to change the order of candidates for each batch of ballots printed. This helps make sure no one gets an unfair advantage just by being listed first.

Party Strategies

In places like Australia, where you often have to rank all candidates, political parties might tell their supporters how to rank their lower choices. This can lead to "preference deals." Smaller parties might agree to direct their voters to a larger party in exchange for support on certain issues. This can also encourage candidates with similar ideas to work together.

Counting the Votes

Historically, IRV elections were counted by hand. Today, computers and special voting machines can help count the votes faster.

In Australia, the first choices are counted by hand at the polling stations. Then, votes for candidates who are not likely to win are transferred to the next choices. This whole process can be finished quickly on election night.

In the United States, many places use voting machines that scan ballots and use software to count the IRV votes. This makes the process much quicker.

What Are the Pros and Cons of IRV?

Wasted Votes and Condorcet Winners

IRV tries to make sure fewer votes are "wasted" compared to other systems where only the top person wins. In other systems, if your candidate doesn't win, your vote might feel like it didn't count. With IRV, your vote can move to your second or third choice if your first choice is eliminated.

However, IRV doesn't always pick the "Condorcet winner." This is the candidate who would win if they went head-to-head against every other candidate.

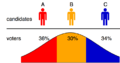

Let's look at an example:

| First choice | A | B | C | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Second choice | B | A | C | B |

| Voters | 36% | 10% | 20% | 34% |

- If only first choices counted: Candidate A would win with 36%.

- With IRV: Candidate B has the fewest first-place votes (10% + 20% = 30%), so B is eliminated. Then, B's voters' next choices are counted. Candidate C gets more of B's second choices and wins with 54%.

- Condorcet Winner: Candidate B would actually win if compared to A (B gets 64% of votes) and also if compared to C (B gets 66% of votes). So, B is the Condorcet winner, but IRV didn't pick B in this example. This can happen if B is a "compromise" candidate that many people like as a second choice.

Resistance to Tricky Voting

IRV is quite good at stopping "tactical voting." This is when voters don't vote for their true favorite but instead try to trick the system to get a better outcome.

However, no voting method is perfect. Sometimes, if voters know a lot about what others will do, they might still try to vote tactically. For example, if you really want Candidate B to win, but you know your favorite Candidate A won't, you might rank B first to help B win.

The "Spoiler Effect"

The "spoiler effect" happens when a candidate who can't win takes away votes from a similar candidate. This can cause a less popular candidate to win.

Supporters of IRV say it helps stop the spoiler effect. With IRV, you can vote for a smaller party or candidate you really like as your first choice. If they get eliminated, your vote then goes to your second choice, who might be a more popular candidate. This means your vote isn't "wasted."

However, if a third-party candidate is quite popular, they can still act as a spoiler. They might take away enough first-choice votes from a mainstream candidate, causing that mainstream candidate to be eliminated. Then, the mainstream candidate's second-choice votes might accidentally help a candidate that many voters dislike.

Proportionality

IRV is a "winner-takes-all" system, meaning only one person wins in each area. It tends to favor larger political parties. Smaller parties usually don't win seats unless they have a lot of support in one area. However, their supporters' votes are still important in deciding the final winner.

Costs

The cost of printing ballots for IRV is similar to other voting methods. However, the counting process can be more complex, which might encourage the use of special software or electronic voting machines.

IRV can save money by combining a primary election and a general election into one. This means there's only one election day instead of two, which can reduce costs.

Negative Campaigning

Some people believe IRV helps reduce "negative campaigning." This is when candidates attack each other. With IRV, candidates might be less likely to attack others because they want to be ranked as a second or third choice by those voters. If you attack another candidate, their supporters might not rank you at all.

Studies have shown that in cities using IRV, candidates spend less time criticizing opponents compared to cities that don't use IRV.

"Plural Voting" Argument

Some critics argue that IRV gives "minority candidate voters two votes." They say that if you vote for a candidate who gets eliminated, your vote then counts for your second choice. Meanwhile, if you vote for a major candidate who stays in the race, your vote only counts once.

However, courts in the United States have rejected this idea. They say that no voter's vote is counted more than once for the same candidate. They explain that IRV is like having a runoff election, but all at once.

History and Use of IRV

A Look Back

The idea behind IRV has been around since the late 1700s. It's similar to a method called the single transferable vote (STV), which started being used in the 1850s.

The first known use of a system like IRV in a government election was in Australia in 1893. It was called a "contingent vote" back then. Australia has used IRV for many years to elect members of its federal parliament and most state parliaments.

Where IRV is Used Today

IRV is used in national elections in several countries:

| Country | Body or office | Type of body or office | Electoral system | Total seats | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | House of Representatives | Lower chamber of legislature | IRV | 151 | |

| Ireland | President | Head of State | |||

| Dáil Éireann | Lower chamber of legislature | Single transferable vote (STV), by-elections using IRV | 158 | ||

| Papua New Guinea | National Parliament | Unicameral legislature | Modified IRV: Ranking of maximum 3 candidates | 109 | |

| United States | President (via Electoral College) | Head of State and Government | Alaska and Maine use IRV to select the state winner. In Maine, 2 electors are allocated to the winner and the others (currently 2) are allocated by congressional district, while in Alaska, the winner gets all electors of the state in the Electoral College system (as Alaska has only one at-large district, the effect is the same). | 7 EVs (out of 538) | |

| House of Representatives | Lower chamber of legislature | IRV in Maine

Nonpartisan primary system with IRV in the second round (among top four candidates) in Alaska. |

3 (out of 435) | ||

| Senate | Lower chamber of legislature | 4 (out of 100) |

Robert's Rules of Order

In the United States, Robert's Rules of Order Newly Revised describes a method similar to IRV. It suggests this type of voting is useful and fair for elections done by mail, especially when it's hard to have more than one round of voting. It helps get a more representative result than just picking the person with the most votes.

However, Robert's Rules also says that if it's possible to have repeated rounds of voting (like in person), that's usually better. This is because voters can change their minds or pick a compromise candidate after seeing the results of earlier rounds.

How IRV Compares to Other Voting Methods

Runoff Voting

IRV gets its name because it's like an "instant runoff." In a regular runoff election, voters might vote multiple times on different days. This allows them to change their minds based on who was eliminated. With IRV, you only vote once, and your choices are set.

Two-Round Systems

The simplest runoff method is the two-round system. Here, only the top two candidates go to a second round of voting. This is used in countries like France. IRV is different because it can have many "rounds" of counting, all from one ballot.

Contingent Vote

The contingent vote is very similar to IRV. If no one wins a majority in the first count, all but the top two candidates are eliminated. Then, the second preferences for those eliminated candidates are counted. This is also done with only one round of voting.

A version of this is used for the Mayor of London election, where voters pick only a first and second choice.

Different Ways to Rank

There are different ways IRV can be set up:

- Optional Preferential Voting: You can rank as many or as few candidates as you want. If your top choices are eliminated, your ballot might become "exhausted" if you didn't rank enough candidates. This is used in Ireland for presidential elections.

- Full-Preferential Voting: You must rank every single candidate. If you don't, your ballot might not count. This is used in Australia for federal elections. Sometimes, this can lead to "donkey voting," where people just rank candidates in order down the ballot if they don't have strong preferences.

Examples of IRV in Action

Five Voters, Three Candidates

Let's imagine an election with Bob, Bill, and Sue. Five voters (a, b, c, d, e) rank them. To win, someone needs 3 or more votes.

| Round 1 | Round 2 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Candidate | a | b | c | d | e | Votes | a | b | c | d | e | Votes |

| Bob | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Sue | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Bill | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | ||||||

In Round 1, Bob and Sue each have 2 votes, and Bill has 1. No one has a majority. Bill is eliminated because he has the fewest votes. Voter 'c' ranked Bill first, so their vote now goes to their second choice, Sue.

In Round 2, Sue now has 3 votes (her original 2, plus voter 'c's transferred vote). Bob still has 2 votes. Sue wins because she has a majority!

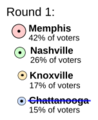

Tennessee Capital Election

Sometimes, the person who wins with IRV isn't the one who had the most first-place votes. Let's look at an example for choosing a capital city in Tennessee.

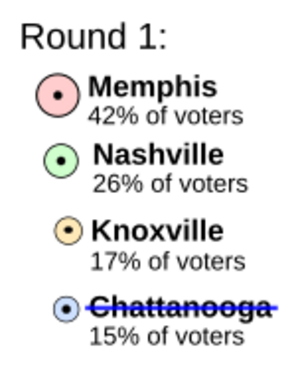

Round 1 – No city gets more than half the votes:

| Votes in round/ City Choice |

1st |

|---|---|

| Memphis | 42% |

| Nashville | 26% |

| Knoxville | 17% |

| Chattanooga | 15% |

Memphis has the most votes (42%), but not a majority. Chattanooga has the fewest votes (15%), so it's eliminated. Its votes go to the voters' second choices (in this example, Knoxville).

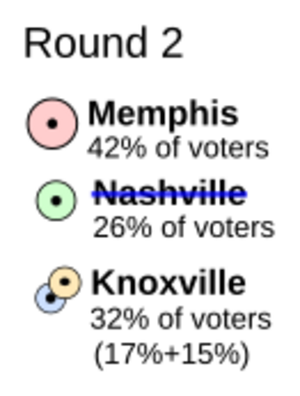

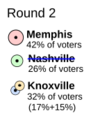

Round 2 – Chattanooga is out. Its votes are added to Knoxville's.

| Votes in round/ City Choice |

1st | 2nd |

|---|---|---|

| Memphis | 42% | 42% |

| Nashville | 26% | 26% |

| Knoxville | 17% | 32% |

| Chattanooga | 15% |

Now, Memphis has 42%, Knoxville has 32%, and Nashville has 26%. Still no majority. Nashville has the fewest votes now, so it's eliminated. Its votes go to the voters' next choices (in this example, Knoxville).

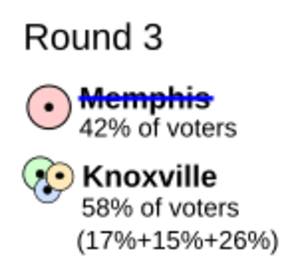

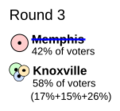

Round 3 – Nashville is out. Its votes are added to Knoxville's.

| Votes in round/ City Choice |

1st | 2nd | 3rd |

|---|---|---|---|

| Memphis | 42% | 42% | 42% |

| Nashville | 26% | 26% | |

| Knoxville | 17% | 32% | 58% |

| Chattanooga | 15% |

Result: Knoxville, which started in third place, now has 58% of the votes and wins!

If this were a simple "first-past-the-post" election (where only the most votes wins), Memphis would have won. But with IRV, Knoxville, a city that many voters preferred as a second or third choice, became the winner.

1990 Irish Presidential Election

| Irish presidential election, 1990 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Candidate | Round 1 | Round 2 | ||

| Mary Robinson | 612,265 | (38.9%) | 817,830 | (51.6%) |

| Brian Lenihan | 694,484 | (43.8%) | 731,273 | (46.2%) |

| Austin Currie | 267,902 | (16.9%) | — | |

| Exhausted ballots | 9,444 | (0.6%) | 34,992 | (2.2%) |

| Total | 1,584,095 | (100%) | 1,584,095 | (100%) |

The 1990 Irish presidential election is another example where IRV changed the outcome. There were three candidates: Brian Lenihan, Austin Currie, and Mary Robinson.

After the first count, Brian Lenihan had the most first-choice votes (43.8%). If it were a "first-past-the-post" election, he would have won. But no one had a majority.

Austin Currie had the fewest votes (16.9%), so he was eliminated. His votes were then transferred to the voters' next choices. Mary Robinson received a large share of Currie's votes (82%). This helped her overtake Lenihan and win the election with 51.6% of the votes in the second round.

2014 Prahran Election (Victoria, Australia)

In the 2014 election for the seat of Prahran in Australia, the IRV system led to a surprising result. The Liberal candidate, Clem Newton-Brown, had the most first-place votes. The Labor candidate, Neil Pharaoh, was second, and the Greens candidate, Sam Hibbins, was third.

However, after several rounds of counting and transferring votes from eliminated candidates, the Greens candidate, Sam Hibbins, ended up winning the seat! This happened because he received many second and third preferences from voters whose first choices were eliminated. He narrowly beat the Liberal candidate. This shows how IRV can allow a candidate who isn't first in the initial count to still win if they are a strong second or third choice for many voters.

| Candidate | Primary vote | First round | Second round | Third round | Fourth round | Fifth round | Sixth round | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clem Newton-Brown (LIB) | 16,582 | 44.8% | 16,592 | 16,644 | 16,726 | 16,843 | 17,076 | 18,363 | 49.6% |

| Neil Pharaoh (ALP) | 9,586 | 25.9% | 9,593 | 9,639 | 9,690 | 9,758 | 9,948 | ||

| Sam Hibbins (GRN) | 9,160 | 24.8% | 9,171 | 9,218 | 9,310 | 9,403 | 9,979 | 18,640 | 50.4% |

| Eleonora Gullone (AJP) | 837 | 2.3% | 860 | 891 | 928 | 999 | |||

| Alan Walker (FFP) | 282 | 0.8% | 283 | 295 | |||||

| Jason Goldsmith (IND) | 247 | 0.7% | 263 | 316 | 349 | ||||

| Steve Stefanopoulos (IND) | 227 | 0.6% | 241 | ||||||

| Alan Menadue (IND) | 82 | 0.2% | |||||||

| Total | 37,003 | 100% | |||||||

2009 Burlington Mayoral Election

| Candidates | 1st Round | 2nd Round | 3rd Round | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Candidate | Party | Votes | ± | Votes | ± | Votes | ± |

| Bob Kiss | Progressive | 2585 | +2585 | 2981 | +396 | 4313 | +1332 |

| Kurt Wright | Republican | 2951 | +2951 | 3294 | +343 | 4061 | +767 |

| Andy Montroll | Democrat | 2063 | +2063 | 2554 | +491 | 0 | −2554 |

| Dan Smith | Independent | 1306 | +1306 | 0 | −1306 | ||

| James Simpson | Green | 35 | +35 | 0 | −35 | ||

| Write-in | 36 | +36 | 0 | −36 | |||

| EXHAUSTED PILE | 4 | +4 | 151 | +147 | 606 | +455 | |

| TOTALS | 8980 | +8980 | |||||

In the 2009 mayoral election in Burlington, Vermont, the IRV winner (Bob Kiss) was different from who would have won with a simple "plurality" system (Kurt Wright). It was also different from the "Condorcet winner" (Andy Montroll).

Some people saw this election as a success because it prevented vote-splitting and most ballots were counted correctly. However, others thought it was a failure because the Condorcet winner didn't win. After this election, Burlington voters decided to stop using IRV for mayoral elections, but later voted to use it for city council elections.

| Party | Candidate | Maximum round |

Maximum votes |

Share in maximum round |

Maximum votes First round votesTransfer votes |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Progressive | Bob Kiss | 3 | 4,313 | 48.0% |

|

|

| Republican | Kurt Wright | 3 | 4,061 | 45.2% |

|

|

| Democratic | Andy Montroll | 2 | 2,554 | 28.4% |

|

|

| Independent | Dan Smith | 1 | 1,306 | 14.5% |

|

|

| Green | James Simpson | 1 | 35 | 0.4% |

|

|

| Write-in | 1 | 36 | 0.4% |

|

||

| Exhausted votes | 606 | 6.7% |

|

|||

See also

In Spanish: Segunda vuelta instantánea para niños

In Spanish: Segunda vuelta instantánea para niños

- Comparison of electoral systems

- First-past-the-post voting (a common voting system where the person with the most votes wins, even if it's not a majority)

- Ranked-choice voting in the United States

- Ranked voting

- Single transferable vote (a similar method used for elections with multiple winners)

Images for kids

-

Example of a full preferential ballot paper from the Australian House of Representatives

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |