Léon Gambetta facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Léon Gambetta

|

|

|---|---|

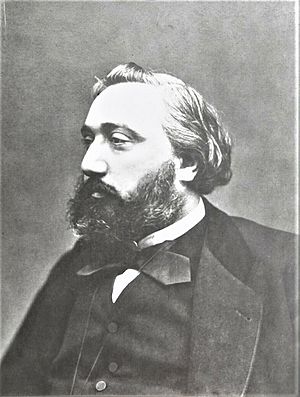

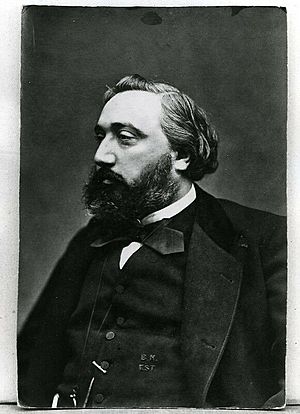

Gambetta photographed by Nadar

|

|

| Prime Minister of France | |

| In office 14 November 1881 – 30 January 1882 |

|

| President | Jules Grévy |

| Preceded by | Jules Ferry |

| Succeeded by | Charles de Freycinet |

| President of the Chamber of Deputies | |

| In office 31 January 1879 – 27 October 1881 |

|

| Preceded by | Jules Grévy |

| Succeeded by | Henri Brisson |

| Minister of the Interior | |

| In office 4 September 1870 – 6 February 1871 |

|

| Prime Minister | Louis-Jules Trochu |

| Preceded by | Henri Chevreau |

| Succeeded by | Emmanuel Arago |

| Member of the Chamber of Deputies | |

| In office 8 June 1869 – 31 December 1882 |

|

| Constituency | Bouches-du-Rhône (1869–71) Bas-Rhin (1871) Seine (1871–76) Paris (1876–82) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 2 April 1838 Cahors, France |

| Died | 31 December 1882 (aged 44) Sèvres, France |

| Political party | Moderate Republican (1863–1869) Republican far-left (1869–1871) Republican Union (1871–1882) |

| Alma mater | University of Paris |

| Profession | Lawyer |

Léon Gambetta (born April 2, 1838 – died December 31, 1882) was an important French lawyer and politician. He was a strong supporter of a republic, a type of government where the people elect their leaders. In 1870, he helped declare the French Third Republic and played a big part in its early years.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Léon Gambetta was born in Cahors, France. His father was a grocer from Genoa, Italy, and his mother was French. People said he got his energy and great speaking skills from his father.

When he was fifteen, Gambetta had an accident and lost sight in his right eye. It later had to be removed. Even with this, he was a very good student in school. After working in his father's shop, he went to Paris in 1857 to study law. He was known among students for being against the emperor's government.

Political Career

Gambetta became a lawyer in 1859. He joined a debating club called the Conférence Molé, which was like a training ground for future politicians. Many French speakers learned how to speak well in public there.

He became famous on November 17, 1868, when he defended a journalist named Delescluze. This journalist was in trouble for honoring a politician who had died resisting a government takeover in 1851. Gambetta used this chance to strongly criticize the government, which made him instantly well-known.

In May 1869, he was elected to the Assembly, which is like a parliament. He chose to represent Marseille. He often spoke out against the Empire in the Assembly. Early in his career, he was influenced by "Le Programme de Belleville," a set of ideas that guided radical politicians in France. This made him a leading voice for the working class.

Declaring the Republic

Gambetta did not want France to go to war with Prussia. However, he did vote for money to support the army. On September 2, 1870, the French army suffered a huge defeat at the Battle of Sedan. The emperor, Napoleon III, surrendered and was captured.

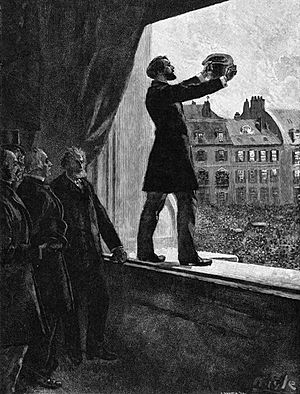

When this news reached Paris on September 3, large protests began. People broke into the meeting place of the Chamber of Deputies, demanding a republic.

Leading the Government of National Defense

Gambetta quickly became a key member of the new Government of National Defense. He became the Minister of the Interior, in charge of internal affairs. He suggested that the government leave Paris to organize resistance from another city, but his idea was not accepted at first.

Later, on October 7, Gambetta himself left Paris in a hot air balloon. He went to Tours and took charge as Minister of the Interior and Minister of War. With the help of a young engineer named Freycinet, he worked very hard to organize a new army. This army might have helped Paris if another city, Metz, had not surrendered. After a French defeat near Orléans in December, the government moved to Bordeaux.

Time in San Sebastián

Gambetta hoped that republicans would win the elections on February 8, 1871. But conservatives and supporters of the monarchy won most of the seats. He had won elections in eight different areas, but the main winner was Adolphe Thiers. Thiers wanted peace, which was different from Gambetta's desire to keep fighting the Prussians.

When Thiers signed a peace treaty on March 1, 1871, Gambetta was very disappointed. He resigned and left France for San Sebastián, a city in Spain.

While in Spain, Gambetta walked on the beaches. Meanwhile, the Paris Commune took control of Paris. Even though he had supported the working class before, Gambetta was against the Commune. He saw it as a "ghastly madness" that was hurting France. He believed in fighting for change through legal means, not through violent uprisings.

Return to Politics

Gambetta soon returned to French politics. On November 5, 1871, he started a newspaper called La Republique française, which became very important. His public speeches were very powerful.

He began to support a more moderate form of republicanism, which he called "opportunism." This meant taking practical steps to achieve goals rather than pushing for extreme changes. He became a leader of the "Opportunist Republicans."

In May 1877, he spoke out against the influence of the church in politics. During a political crisis in May 1877, Gambetta famously told President MacMahon to either accept the will of the parliament or resign. MacMahon eventually gave in and formed a republican government.

Gambetta chose not to run for president himself, supporting Jules Grévy instead. In January 1879, he became the president of the Chamber of Deputies. This job meant he led the debates, but he still sometimes gave speeches, like one supporting an amnesty (forgiveness) for those involved in the Paris Commune.

In 1881, he led a movement to change how deputies were elected, from small local districts to larger regional lists. This change was passed by the Assembly but rejected by the Senate.

Despite this, his supporters won a large majority in the next election. On November 24, 1881, President Grévy asked Gambetta to form a government, known as Le Grand Ministère. Many people unfairly accused him of wanting to be a dictator. His government lasted only sixty-six days, falling on January 26, 1882. He had wanted to work closely with Britain, especially in Egypt, and his ideas were later proven right.

On December 31, 1882, Gambetta died at his home near Sèvres. He died from stomach cancer. A month earlier, he had been accidentally shot by a revolver, but that injury was not life-threatening. Many artists were with him when he died, creating different images of him. His public funeral was held on January 6, 1883.

Personal Life

Léon Gambetta had a very close relationship with Léonie Léon. She was the daughter of a French artillery officer. They met in 1871, and she became his trusted companion and advisor in all his political plans. She often refused to marry him, fearing it would harm his political career. It is believed she finally agreed to marry him just before his accidental injury and death.

Her influence on Gambetta was significant. Their letters show how much he relied on her. Gambetta believed that France and Germany could improve their relationship. He traveled secretly to learn more about Germany and nearby countries. When he died, France lost a clear thinker who was greatly needed.

Legacy

A large monument to Léon Gambetta was built in Paris between 1884 and 1888. It was placed in the central area of the Louvre Palace. This monument was very important because Gambetta was seen as the founder of the French Third Republic. Its size showed that the idea of a republic had finally won over the idea of a monarchy in France. Most of the monument's bronze sculptures were melted down in 1941 by German forces during World War II. The rest of the monument was taken apart in 1954.

In 1920, a stone urn holding Gambetta's heart was placed in the Panthéon in Paris. The stone used for the urn was the same type used for Napoleon's tomb.

Gambetta's Government (November 14, 1881 – January 26, 1882)

- Léon Gambetta – Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs

- Jean-Baptiste Campenon – Minister of War

- Pierre Waldeck-Rousseau – Minister of the Interior

- François Allain-Targé – Minister of Finance

- Jules Cazot – Minister of Justice

- Maurice Rouvier – Minister of the Colonies and of Commerce

- Auguste Gougeard – Minister of Marine (Navy)

- Paul Bert – Minister of Public Instruction (Education) and Worship

- Antonin Proust – Minister of the Arts

- Paul Devès – Minister of Agriculture

- David Raynal – Minister of Public Works

- Adolphe Cochery – Minister of Posts and Telegraphs

See also

In Spanish: Léon Gambetta para niños

In Spanish: Léon Gambetta para niños

- List of works by Alexandre Falguière

Images for kids

-

Photo of Gambetta by Nadar, 1871