Jules Grévy facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Jules Grévy

|

|

|---|---|

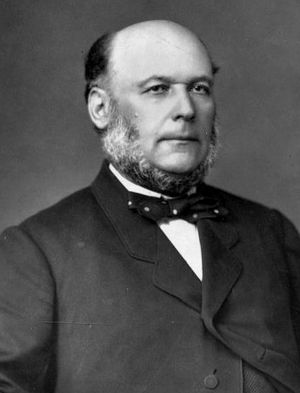

Grévy c. 1880

|

|

| President of France | |

| In office 30 January 1879 – 2 December 1887 |

|

| Prime Minister | Jules Armand Dufaure William Henry Waddington Charles de Freycinet Jules Ferry Léon Gambetta Charles Duclerc Armand Fallières Jules Ferry Henri Brisson René Goblet Maurice Rouvier |

| Preceded by | Patrice de MacMahon |

| Succeeded by | Sadi Carnot |

| President of the Chamber of Deputies | |

| In office 13 March 1876 – 30 January 1879 |

|

| Preceded by | Gaston d'Audiffret-Pasquier |

| Succeeded by | Léon Gambetta |

| President of the National Assembly | |

| In office 16 February 1871 – 2 April 1873 |

|

| Preceded by | Eugène Schneider |

| Succeeded by | Louis Buffet |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 15 August 1807 Mont-sous-Vaudrey, France |

| Died | 9 September 1891 (aged 84) Mont-sous-Vaudrey, France |

| Political party | Moderate Republicans |

| Spouse | Coralie Grévy |

| Relatives | Albert Grévy (brother) |

| Alma mater | University of Paris |

Jules Grévy (born François Judith Paul Grévy; 15 August 1807 – 9 September 1891) was a French lawyer and politician. He served as the President of France from 1879 to 1887. Grévy was a leader of the Moderate Republicans. His predecessors were monarchists who wanted to bring back the French monarchy. Because of this, Grévy is seen as the first true republican president of France.

Grévy was born in a small town in the Jura area. He moved to Paris and became a lawyer. He also became an activist who supported a republic. His political career began after the French Revolution of 1848. He became a member of the National Assembly during the French Second Republic. He was known for not supporting Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte. He also believed the executive branch (the president's power) should have less authority. Louis-Napoléon took power in a coup d'état in 1851. Grévy was briefly put in prison and then left politics for a while.

When the Second French Empire ended and the Republic returned in 1870, Grévy became important in politics again. He held high positions in the National Assembly and the Chamber of Deputies. In 1879, he was elected president of France. During his time as president, Grévy made sure the president's power was less than the Parliament's. In foreign policy, he wanted peaceful relationships with other countries and was against colonialism (taking over other lands). He was reelected in 1885. However, he had to resign two years later because of a political issue involving his son-in-law. Grévy himself was not involved in any wrongdoing. His nearly nine years as president helped make the French Third Republic strong and stable.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Grévy was born on 15 August 1807 in Mont-sous-Vaudrey, in the department of Jura. His family believed in a republic. His grandfather, Nicolas Grévy, was a local judge. Jules's father, François Hyacinthe Grevy, joined the French Revolutionary Army in 1792. He became a battalion commander and fought in the Revolutionary Wars. Later, he retired to Mont-sous-Vaudrey and ran a factory that made roof tiles.

At age 10, Grévy started school in Poligny. He continued his studies in Besançon, Dole, and then at a law school in Paris. In 1837, he became a lawyer in Paris. He was known for his strong republican beliefs during the July Monarchy. He began his political work by defending people involved in a failed uprising in 1839.

Role in the Second Republic

In 1848, a revolution in France ended the rule of kings. This led to the creation of the Second Republic. Grévy was appointed as a government representative for the Jura department. In April 1848, he was elected to the Constituent National Assembly. This assembly was created to write a new constitution.

Grévy wanted a "strong and fair Republic that people would like." He saw that Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte might become very powerful. So, he started to argue for a weaker executive branch. During the debates about the new Constitution, he became famous for saying that the president should not be chosen by everyone voting directly. Instead, he suggested that the main leader should be chosen and removed by the elected National Assembly. This idea was called the "Grévy Amendment," but it was not accepted. In December 1848, Bonaparte was elected president of France.

Grévy became vice-president of the National Assembly in April 1849. He spoke out against the president's decision to send troops to fight against the short-lived Roman Republic. However, the invasion happened and brought back the rule of the Pope. In 1851, Grévy's fear that Louis-Napoléon wanted to stay in power forever came true. The president took control of the government by force in a coup d'état on 2 December. Grévy was arrested and put in Mazas Prison. He was released soon after. He then stopped being involved in politics during the Second French Empire, which was led by Emperor Napoleon III. He went back to working as a lawyer.

Return to Politics in the Third Republic

Grévy started his political career again in the last years of the Empire. In 1868, he was elected to the Corps législatif, which was a law-making body. He quickly became a leader of the group that opposed the government. Along with Adolphe Thiers and Léon Gambetta, he was against France declaring the Franco-Prussian War in 1870. He also spoke out against the socialist uprising known as the Paris Commune. After Thiers died in 1877, Grévy became the head of the Republican Party.

After the Empire fell during the Franco-Prussian War, Grévy was elected to represent Jura and Bouches-du-Rhône in the National Assembly of the new Third Republic in 1871. He was the president of the Assembly from February 1871 to April 1873. He resigned because some members of the Right (a political group) were against him. On 8 March 1876, Grévy became president of the Chamber of Deputies. He did such a good job that when President Marshal de MacMahon resigned, Grévy was the clear choice for President of the Republic. On 30 January 1879, he was elected without any opposition from the republican parties.

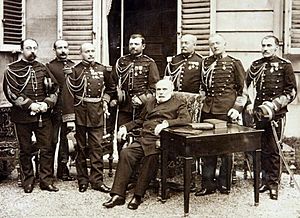

Grévy's Presidency

During his time as president, Grévy wanted to reduce the president's powers. He believed the legislature (the Parliament) should be stronger. On 6 February 1879, soon after becoming president, he gave a speech. He said he would always respect the wishes of the nation as expressed by its elected bodies. This idea of a president with limited power influenced many later presidents of the Third Republic.

In foreign policy, he worked for peaceful relationships, especially with the German Empire. He resisted calls for revenge after the difficult defeat in the Franco-Prussian War. He also opposed colonial expansion. Inside France, his presidency saw reforms that aimed to reduce the influence of the church in government. These reforms happened especially when Charles de Freycinet was prime minister. In 1880, Grévy approved a law that gave amnesty (forgiveness) to the people involved in the Paris Commune.

On 28 December 1885, Grévy was elected for another seven years as president. However, two years later, in December 1887, he had to resign. This was due to a political issue involving his son-in-law, Daniel Wilson. Wilson was found to be selling awards from the Legion of Honour. Even though Grévy himself was not involved in this, he was seen as indirectly responsible because Wilson used his access to the Élysée (the presidential palace). Under pressure from the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate, Grévy resigned on 2 December. In his last message to the two chambers, he said that while he had the right to resist, it was wiser and more patriotic to step down.

Personal Life and Legacy

Grévy married Coralie Frassie in 1848. She was the daughter of a tanner. They had one daughter, Alice (1849-1938), who married Daniel Wilson in 1881.

Jules Grévy died in his hometown of Mont-sous-Vaudrey on 9 September 1891, from a lung condition. His state funeral was held on 14 September.

Grévy was a member of a masonic lodge called "La Constante Amitié." His involvement in this group was connected to his policies, especially in the effort to separate church and state in France.

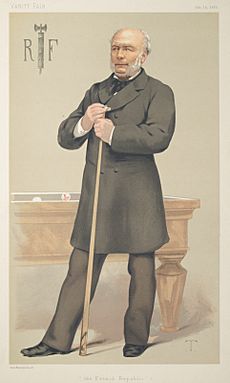

In his private life, Grévy loved playing billiards. He was even shown playing billiards in a cartoon published in Vanity Fair magazine in 1879.

A type of Lilac, Syringa Vulgaris 'President Grévy', is named after him. The Grévy's zebra is also named after him.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Jules Grévy para niños

In Spanish: Jules Grévy para niños

| Stephanie Wilson |

| Charles Bolden |

| Ronald McNair |

| Frederick D. Gregory |