Jean Moulin facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Jean Moulin

|

|

|---|---|

Moulin in 1937

|

|

| Born | 20 June 1899 |

| Died | 8 July 1943 (aged 44) Near Metz, Occupied France

|

| Resting place | Panthéon, Paris |

| Occupation | Prefect |

| Known for | First President of the National Council of the Resistance |

| Parent(s) | Antoine-Émile Moulin Blanche Élisabeth Pègue |

Jean Moulin (born June 20, 1899 – died July 8, 1943) was a brave French leader during World War II. He was a key figure in the French Resistance, a secret group that fought against the German occupation of France. Jean Moulin became the first president of the National Council of the Resistance in May 1943.

Before the war, he worked for the French government as a Prefect (a high-ranking local official) in different areas like Aveyron and Eure-et-Loir. Today, he is remembered as one of the greatest heroes of the French Resistance. He worked hard to unite the many different Resistance groups under the leadership of Charles de Gaulle. Sadly, he was captured and died while being held by the Gestapo, the German secret police.

Contents

Jean Moulin's Early Life

Jean Moulin was born on June 20, 1899, in Béziers, France. His father, Antoine-Émile Moulin, was a teacher and a member of a group called Freemasons. Jean's grandfather had also been a fighter against the government in 1851.

Jean had a quiet childhood with his sister, Laure, and his brother, Joseph, who sadly passed away in 1907. Jean went to Lycée Henri IV in Béziers, where he was an average student.

In 1917, he started studying law at the University of Montpellier. Thanks to his father's help, he got a job as an assistant to the local government leader (prefect) in Hérault. This was during the time when Raymond Poincaré was president of France.

Military Service During World War I

Jean Moulin joined the army on April 17, 1918, during World War I. He was part of the 2nd Engineer Regiment in Montpellier. In September, after quick training, he went with his regiment to the front lines in the Vosges region.

His regiment was getting ready for a big attack planned for November 13, but the war ended on November 11, 1918, when the Armistice was signed.

Even though Jean Moulin did not fight directly in battles, he saw the terrible effects of war. He saw the damage to battlefields and villages, and the sad state of prisoners of war. He even helped bury soldiers who had died near Metz.

After the war, he stayed in the army for a short time, working in different roles like a carpenter and a telephonist. He left the army in November 1919 and immediately went back to his job as an assistant at the local government office in Montpellier.

Life Between the World Wars

After World War I, Jean Moulin continued his law studies. His job at the local government office helped him pay for university and learn about politics. He earned his law degree in July 1921. He then started working in government administration. He became a chief of staff in Savoie in 1922 and then a sous-préfet (a lower-ranking local official) in Albertville from 1925 to 1930.

In September 1926, Jean Moulin married Marguerite Cerruti, a 19-year-old singer. However, their marriage did not last long. They divorced because Marguerite found life boring and often disappeared.

In 1930, Moulin became sous-préfet of Châteaulin, Brittany. At the same time, he drew political cartoons for a newspaper called Le Rire using the pen name Romanin. He also drew pictures for books by the poet Tristan Corbière. He made friends with other poets in Brittany, like Saint-Pol-Roux and Max Jacob.

In 1932, Pierre Cot, a politician, made Moulin his second-in-command when Cot was the Foreign Minister. In 1933, Moulin became sous-préfet of Thonon-les-Bains. He also continued to work for Cot in the Air Ministry.

In 1936, Moulin again became chief of staff for Cot in the Air Ministry. In this role, Moulin helped the Second Spanish Republic by sending them planes and pilots during the Spanish Civil War. In January 1937, he became France's youngest préfet in the Aveyron area.

As a Prefect During World War II

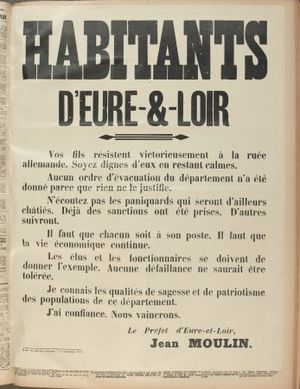

In January 1939, Moulin became the prefect of the Eure-et-Loir area, based in Chartres. When war was declared against Germany, he asked many times to be sent to the front lines, saying his place was not in a quiet area. But the Minister of the Interior made him stay in Chartres. The war soon reached him there with German air strikes and many scared refugees.

As German troops got closer to Chartres, he wrote to his parents, "If the Germans — who are capable of anything — make me say dishonorable words, you already know, it is not the truth." In mid-June, German soldiers entered Chartres.

On June 17, 1940, Moulin was arrested by the Germans. He refused to sign a false statement saying that three Senegalese soldiers had killed civilians. In reality, German bombs had killed those civilians. This act of defiance left him with a scar on his neck, which he often hid with a scarf. This is why many famous pictures of Jean Moulin show him wearing a scarf.

Because he was a member of the Radical Party, the new French government, led by Marshal Philippe Pétain, removed him from his job on November 2, 1940. This government was called the Vichy regime and worked with the Germans. After this, Moulin started writing a diary about his resistance against the Nazis in Chartres. This diary was later published after France was freed.

Joining the French Resistance

Jean Moulin decided not to work with the Germans. He left Chartres and went to his parents' hometown, Saint-Andiol. He then joined the French Resistance, specifically the organization called Free France. Using the fake name Joseph Jean Mercier, he went to Marseille. There, he met other Resistance members, including Henri Frenay.

In September 1941, Moulin traveled to London, passing through Spain and Portugal. On October 24, he met with Charles de Gaulle, the leader of Free France. De Gaulle was very impressed by Moulin, calling him "A great man. Great in every way."

Moulin told de Gaulle about the state of the French Resistance. De Gaulle trusted Moulin's abilities and gave him a very difficult job: to coordinate and unite all the different Resistance groups in France. On January 1, 1942, Moulin parachuted back into France and met with the leaders of several Resistance groups, using codenames like Rex and Max. These leaders included:

- Henri Frenay from Combat

- Emmanuel d'Astier from Libération

- Jean-Pierre Lévy from Francs-tireurs

- Pierre Villon from Front national

- Pierre Brossolette from Comité d'action socialiste

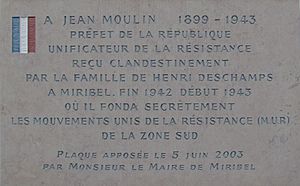

Moulin was very successful. The first three of these groups joined together to form the United Resistance Movement (Mouvements Unis de la Résistance, or MUR) in January 1943. The next month, Moulin went back to London with Charles Delestraint, who led the new Armée secrète (Secret Army), which was the military part of the MUR.

Moulin left London again on March 21, 1943. His new mission was to unite all of the French Resistance by creating the National Resistance Council (Conseil national de la Résistance, or CNR). This was an even harder task because other Resistance groups wanted to stay independent.

Creating the National Resistance Council

Jean Moulin succeeded in his difficult task. He got all the different parts of the French Resistance to agree on a single plan and to recognize Charles de Gaulle as their leader. This included various Resistance groups, as well as outlawed labor unions and political parties. Because Moulin was known for his left-wing views, he even managed to get the Communist Resistance groups to cooperate, even though they had been unsure about de Gaulle.

The unified plan was written in a document called the 'Program of the National Council of the Resistance'. This program was adopted on March 15, 1944. It was a short document, less than ten pages long. It had two main parts:

- An "immediate action plan" for how the Resistance would fight before France was freed.

- "Measures to be applied after the territory is liberated," which was like a government plan for how to remove Nazi influence from French society. It also included long-term goals like bringing back fair elections, freedom of the press, the right to form unions, and social security.

The first meeting of the CNR happened in Paris on May 27, 1943. Representatives from eight Resistance movements, two major labor unions, and the six most important political parties of the Third Republic attended.

This show of unity was very important for de Gaulle. It strengthened his position with the Allied forces (like the US and Britain), who were thinking about how to govern France after the war themselves. By bringing together so many different groups, the CNR made the French Resistance look like a strong, unified movement. With Charles de Gaulle as its recognized head, it also made him a stronger national leader who could govern France after the war.

Jean Moulin was helped in his work by his personal assistant, Laure Diebold.

Capture and Death

On June 21, 1943, Jean Moulin was arrested during a secret meeting with other Resistance leaders. The meeting was at the home of Dr. Frédéric Dugoujon in Caluire-et-Cuire, near Lyon. Several other leaders were also arrested, including Henri Aubry and Raymond Aubrac. René Hardy, another Resistance member, was also there, but it's unclear why, and he either escaped or was allowed to leave.

Moulin and the other Resistance leaders were taken to Montluc Prison in Lyon. There, he was questioned and badly treated by Klaus Barbie, who was the head of the Gestapo in Lyon. Witnesses said that Moulin's fingernails were removed, his fingers were broken, and his wrists were severely injured. He was beaten until his face was unrecognizable and he fell into a coma.

After these terrible sessions, Barbie ordered that Moulin be shown to other imprisoned Resistance members as a warning. The last time he was seen alive, he was still in a coma, his head swollen and bandaged.

There is some uncertainty about the exact details of Moulin's death. His death certificate, issued by the German forces, says he died near the Metz railway station. However, there are different stories about exactly when and where he died.

Theories About Betrayal

Many people have wondered who might have betrayed Jean Moulin, leading to his arrest. Many Resistance members who knew what happened died during the war.

Some suspicions have focused on René Hardy, the Resistance member who was present at the meeting where Moulin was arrested. Hardy was arrested by the Gestapo but then either escaped or was allowed to flee. After the war, he was tried twice for his possible role in the arrest, but he was found not guilty both times because there wasn't enough evidence.

Some theories have also pointed to Communists, but there has never been any strong proof to support these claims. Historians like Henri Noguères and Jean-Pierre Azéma have rejected these conspiracy theories.

At the trial of Klaus Barbie in 1987, his lawyer tried to suggest that Moulin was betrayed by other Resistance members, rather than Barbie being fully responsible. This attempt failed to acquit Barbie but led to many different conspiracy theories about who betrayed Moulin.

Some authors have suggested that Moulin was a "Soviet agent" (a spy for the Soviet Union). However, leading historians have found no evidence to support these claims. For example, the British intelligence officer Peter Wright made such claims in his book Spy Catcher, but his allegations were based on secret documents that no historian has ever seen.

It has also been suggested that Moulin was betrayed by Communists, with some theories pointing to Raymond Aubrac and his wife, Lucie. However, a Paris court later ruled that a book making these claims was "public defamation" (spreading false and damaging information).

Jean Moulin's Legacy

Ashes believed to be Jean Moulin's were first buried in Le Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris. Later, on December 19, 1964, they were moved to the Panthéon, a special building where France's greatest heroes are honored. The speech given at this ceremony by André Malraux, a famous writer and government minister, is one of the most well-known speeches in French history.

In France, Jean Moulin is taught in schools as a symbol of the French Resistance. He represents civic duty, strong morals, and love for one's country. As of 2015, Jean Moulin was the fifth most popular name for a French school. Many streets and even a Paris metro station are named after him.

The famous photograph of Jean Moulin wearing a fedora hat and a scarf has become a popular image of him and the Resistance movement. In the picture, he seems to be hiding, which fits with his secret life in the Resistance. However, this photo was actually taken in February 1940, before he officially joined the Resistance.

In 1967, the Centre national Jean-Moulin de Bordeaux was created in Bordeaux. It holds important documents about World War II and the Resistance. It also helps people learn and research Jean Moulin's role in the Resistance. Another Resistance member, Antoinette Sasse, left money in her will to create The Musée Jean Moulin in 1994.

Several films have been made about Jean Moulin's life. The 1969 film Army of Shadows shows some events from his war experience. Two French TV films, Jean Moulin (2002) and Jean Moulin, une affaire française (2003), also tell his story.

In 1993, France issued special commemorative coins (2, 100, and 500 franc coins) showing a part of Moulin's image against the Cross of Lorraine, using his well-known fedora-and-scarf photograph.

Images for kids

-

Tribute to Jean Moulin in the Rail station of Metz.

See also

In Spanish: Jean Moulin para niños

In Spanish: Jean Moulin para niños

- Hôtel Terminus

- Lionel Floch

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |