History of British Columbia facts for kids

The history of British Columbia tells the story of this amazing place, from when the first people arrived thousands of years ago until today. Before Europeans came, many different First Nations groups lived here for a very long time.

European explorers started visiting the region in the late 1700s and early 1800s. After a disagreement about the border between the UK and the US was settled in 1846, two colonies were created: Vancouver Island in 1849 and the colony of British Columbia on the mainland in 1858. These two colonies joined together in 1866 to form one single colony. Later, on July 20, 1871, this colony became part of Canada.

Contents

First Peoples of British Columbia

People have lived in what is now British Columbia for thousands of years. Scientists have found signs of human life here from as far back as 13,543 years ago! There might even be older sites underwater.

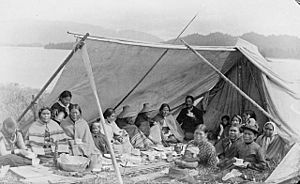

The land itself helped shape the cultures of these early peoples. In some places, it allowed them to build permanent villages and create complex societies with many different languages. British Columbia is often divided into three main cultural areas: the Northwest Coast, the Plateau, and the North. First Nations in each area developed unique ways of life that fit the resources around them. For example, salmon was a very important food source for many groups across British Columbia.

Before Europeans arrived, British Columbia was home to many Indigenous peoples who spoke over 30 different languages. Some of these languages include Haida, Kwak̓wala, Nuu-chah-nulth, Squamish, and Tsimshian. These groups often visited and traded with each other, even across the water between Vancouver Island and the mainland.

Because there was so much natural food, like salmon and cedar, the people on the coast could spend time on other things. They developed amazing art, complex political systems, and even engaged in warfare.

Early European Explorers

The first Europeans to visit what is now British Columbia were Spanish sailors. Some people think that Juan de Fuca, a Greek sailor working for Spain, might have explored the coast in the 1590s. The waterway between Washington State and Vancouver Island is now called the Strait of Juan de Fuca after him.

Spanish Journeys

While there's a theory that Sir Francis Drake might have explored the British Columbia Coast in 1579, the first officially recorded trip was by Juan Francisco de la Bodega y Quadra in 1775. He sailed along the Pacific coast, claiming the land for Spain. During his trip, some of his crew were attacked by local people near Destruction Island.

In 1774, a Spanish navigator named Juan José Pérez Hernández from Mexico sailed north to look for Russian settlements and claim land for Spain. He reached 55° North, becoming the first European to see the Queen Charlotte Islands and Vancouver Island. He traded with local people near Estevan Point but didn't land. His trip had to end early because they ran out of supplies.

Since Hernández's first trip didn't achieve all its goals, Spain sent another expedition in 1775. This one was led by Bruno de Heceta and included Juan Francisco de la Bodega y Quadra. After some difficulties, de Heceta returned, but Quadra continued north, reaching what is now Sitka, Alaska. During this trip, the Spanish made sure to land several times and officially claim the lands for Spain, while also checking for Russian settlements.

British Explorers and the Nootka Crisis

Three years later, in 1778, British Royal Navy captain James Cook arrived. He was looking for the Northwest Passage. He landed at Nootka Sound on Vancouver Island, where he and his crew traded with the Nuu-chah-nulth First Nation. When his crew sold the sea otter furs they got, they made a huge profit. This encouraged many more traders to come to the British Columbia coast, leading to more trade with the Indigenous peoples.

In 1788, an English explorer named John Meares sailed from China and explored Nootka Sound. He bought some land from a local chief named Maquinna and built a trading post there.

In 1789, a Spanish commander named Esteban José Martínez built a fort called Fort San Miguel at Nootka Sound. Spain already considered this land theirs from earlier explorations. Martínez seized several British ships, including Captain Meares's. This led to the Nootka Crisis, which almost caused a war between Britain and Spain.

The Spanish later rebuilt the fort. However, the Nootka Crisis ended with Britain gaining more power in the region. Spanish influence ended in 1795 after an agreement called the Nootka Convention.

Later British Journeys (1790s–1821)

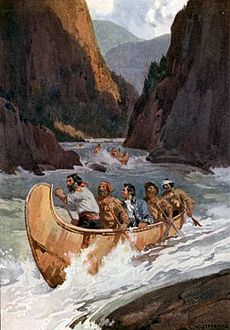

After this, European explorer-traders from eastern Canada started to discover British Columbia. Three important figures from this time were Sir Alexander Mackenzie, Simon Fraser, and David Thompson. They worked for the North West Company and wanted to find a river route to the Pacific Ocean, especially using the Columbia River, to expand the North American fur trade.

In 1793, Mackenzie became the first European to cross North America overland north of Mexico. He and his crew entered the region through the Rocky Mountains using the Peace River. They reached the ocean near present-day Bella Coola. Soon after, Mackenzie's friend, John Finlay, started the first permanent European settlement in British Columbia, Fort St. John.

Simon Fraser was the next to try and find the Columbia River's path. From 1805 to 1809, Fraser and his crew explored much of British Columbia's interior, setting up several forts. Fraser's journey took him down the river that is now named after him, the Fraser River, to the area of present-day Vancouver. Even though both Mackenzie and Fraser reached the Pacific, their routes were too difficult for trade.

It was David Thompson who found the Columbia River and followed it to its mouth in 1811. However, he couldn't claim the land for Britain because American explorers Lewis and Clark had already claimed it for the United States six years earlier.

From Fur Trade to Colonies (1821–1858)

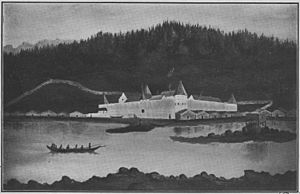

More Europeans started arriving in the mid-1800s, especially fur traders looking for sea otters. Even though British Columbia was technically part of British North America, the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) mostly ran it after joining with the North West Company in 1821. The central part of the mainland was called the New Caledonia District. It was managed from Fort St. James. The southern interior was called the Columbia District and was managed from Fort Vancouver (in present-day Washington State).

Throughout the 1820s and 1830s, the HBC controlled almost all trading in the Pacific Northwest. The company's main goal was to discourage any settlement, including American settlers, because it interfered with the fur trade.

Fort Vancouver was the center of the fur trade on the Pacific Coast. Its influence reached from the Rocky Mountains to Hawaii and from Alaska to California. At its peak, Fort Vancouver oversaw many trading posts, ports, ships, and employees. For many American settlers, the fort was also the last stop on the Oregon Trail where they could get supplies before settling.

By 1843, the Hudson's Bay Company had many posts in the Columbia Department, including Fort Vancouver, Fort Langley, and Fort Simpson.

Because so many different languages were spoken in BC, a special trade language called Chinook Jargon developed. It wasn't a full language but was used for trade and communication between First Nations and early Europeans.

Fort Victoria was built in 1843 as a trading post. It also helped protect HBC's interests and show that Britain claimed Vancouver Island and the nearby Gulf Islands. More American settlers arriving on the Oregon Trail led to a border dispute called the Oregon boundary dispute. The British wanted the border to be at the Columbia River.

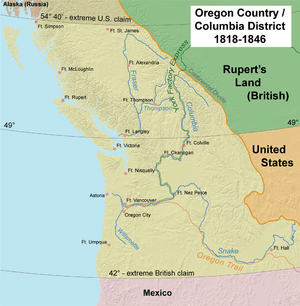

In 1844, the United States wanted to claim the entire Columbia District. President James K. Polk was willing to draw the border at the 49th parallel. When the British said no, Polk stopped talks, and some Americans started using slogans like "Fifty-Four Forty or Fight!" However, with the Mexican–American War starting, Polk was ready to compromise again. The Oregon boundary dispute was settled in 1846 with the Treaty of Washington. This agreement set the border at the 49th parallel from the Rocky Mountains to the ocean, but Vancouver Island remained British territory.

This meant the HBC's Columbia Department had to change its main base. It moved north to Fort Victoria, which was founded by James Douglas.

In 1849, the Colony of Vancouver Island was created, and in 1851, James Douglas became its Governor. Douglas, often called the "father of British Columbia," set up colonial systems in Victoria. He also started buying land for settlement and industry by signing 14 treaties, known as the Douglas Treaties, between 1850 and 1854.

Meanwhile, on the mainland, the New Caledonia area continued to focus on the fur trade. There were few non-Indigenous people there, mostly HBC employees and their families. Douglas also oversaw this area. The Hudson's Bay Company didn't encourage settlement because it interfered with the profitable fur trade. The British didn't do much to claim control over the Indigenous peoples of the area. According to a rule from 1763, large settlements by non-Indigenous people were not allowed until the land was given up by treaty.

Colonial British Columbia (1858–1871)

In 1858, gold was discovered along the Thompson River, near what is now Lytton, British Columbia. This started the Fraser Canyon Gold Rush. When news of gold in British territory reached San Francisco, Victoria quickly became a busy place. Many prospectors, business people, and suppliers came from all over the world, mostly through San Francisco. The Hudson's Bay Company's Fort Langley became a busy starting point for many prospectors heading up the river.

It was hard for First Nations and explorers to talk to each other because they spoke so many different languages. The trade language, Chinook Jargon, grew and changed to include English and French words. This jargon became widely used by First Nations and early Europeans for communication and trade. Even though it's not used much today, many place names in British Columbia come from Chinook Jargon.

At this time, the region wasn't under formal colonial rule. Governor Douglas was worried about so many Americans coming in (around 20,000). He placed a gunboat at the mouth of the Fraser River to collect fees from those going upstream.

When news of the Fraser Canyon Gold Rush reached London, the British government officially made the mainland a Crown colony on August 2, 1858. They named it the Colony of British Columbia. Richard Clement Moody was chosen to establish British order and make the new colony a strong British presence on the Pacific coast. He brought the Columbia Detachment with him.

Richard Clement Moody and the Royal Engineers

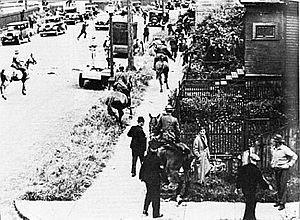

Moody arrived in British Columbia in December 1858 with the Royal Engineers. He became the first Lieutenant-Governor of British Columbia and Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works. Moody wanted to start building a capital city right away. However, he first had to deal with some trouble at a settlement called Hill's Bar, which led to an event known as "Ned McGowan's War". Moody led his Engineers and a judge to Yale to calm down a group of American miners, and they restored order peacefully.

Founding New Westminster

Moody wanted to build a beautiful city in the wilderness of British Columbia. He chose the location for the new capital, New Westminster, because it was a great strategic spot with a good port. He was also impressed by the beauty of the area.

Moody also designed the first Coat of arms of British Columbia.

However, Moody's plans were often held back by not having enough money and by disagreements with Governor Douglas.

Challenges for Moody and Douglas

During his time in British Columbia, Richard Clement Moody had many disagreements with Sir James Douglas, who was the Governor of Vancouver Island. Their areas of authority sometimes overlapped. Douglas often seemed to disrespect the Engineers and their work.

Despite these challenges, many historians believe Moody's achievements were impressive, especially considering the lack of funds and Douglas's opposition.

Other Developments

Moody and the Royal Engineers also built many roads. These included what would become Kingsway, connecting New Westminster to False Creek, and the North Road between Port Moody and New Westminster. They also built parts of the Cariboo Road. Moody named Burnaby Lake after his private secretary, Robert Burnaby. Port Moody is also named after him. It was set up to protect New Westminster from possible attacks.

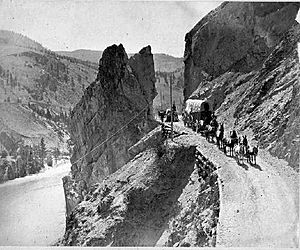

By 1862, the Cariboo Gold Rush was in full swing, bringing in another 5,000 miners. Governor Douglas sped up the building of the Great North Road, also known as the Cariboo Wagon Road, which went up the Fraser Canyon to the goldfields around Barkerville.

During this gold rush, the colony started to change. More British colonists settled down, starting businesses, sawmills, fishing, and farming. With this stability, people started to complain about the governor not being present and the lack of responsible government. These complaints were led by John Robson, a newspaper editor who would later become a premier. Douglas was eventually replaced in 1864, and the colony finally got an assembly and a resident governor.

The Royal Engineers were disbanded in July 1863. Many of them chose to stay in British Columbia.

Another major gold rush happened in the Cariboo region from 1861 to 1864. The large number of gold miners led to the creation of basic infrastructure in BC, especially the Cariboo Wagon Road, which connected the Lower Mainland to the rich goldfields. However, the huge costs of building this road left BC in debt by the mid-1860s. Because of this large debt, the mainland and Vancouver Island became one colony named British Columbia in 1866, with its capital in Victoria.

Joining Canada Debate

In 1867, British Columbia had three main choices: stay a British colony, join the United States, or join the newly formed Dominion of Canada. Many people in Britain thought their North American colonies would eventually leave the British Empire.

Financially, joining the United States seemed to make sense because British Columbia's economy was closely tied to San Francisco, Washington, and Oregon. American money was widely used in the colony. The American transcontinental railroad, completed in 1869, made travel to Ottawa or Washington much faster. With the gold rushes ending, many American miners had left, and the future looked uncertain unless BC joined the fast-growing economies of the Pacific states.

After the United States bought Alaska in 1867, having American territory to both the north and south made British residents worry about their colony's future. Some believed that the people in British Columbia wanted to join the US.

However, most British Columbians did not publicly support joining the United States. Support for joining Canada grew over time. Many British-born colonists eventually supported joining Canada as the best way to stay connected to Britain.

In August 1869, London made it clear that they wanted British Columbia to join Canada. In February 1870, Governor Anthony Musgrave successfully convinced the Legislative Council to support joining Canada. Musgrave proposed an attractive plan: Canada would take on the colony's debt and build a new transcontinental railway. This railway would reduce BC's reliance on the American railroad. The United States was busy with its own issues, so the idea of expanding into British Columbia faded.

Entry into Canada (1871–1900)

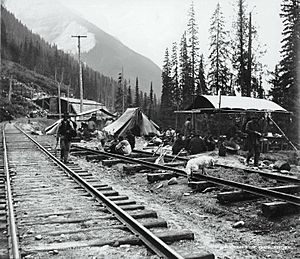

The difficult economic situation after the gold rushes, along with the desire for a truly responsible and representative government, led to strong pressure for British Columbia to join Canada. The Confederation League, led by future premiers like Amor De Cosmos and John Robson, played a big role in this. So, on July 20, 1871, British Columbia became the sixth province to join Canada. In return, Canada took on BC's large debt and promised to build a railway from Montreal to the Pacific coast within 10 years.

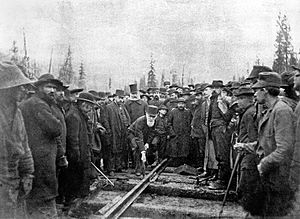

The railway promise became the most important reason for British Columbia to stay in Canada. The Canadian Pacific Railway's last spike was driven in at Craigellachie on November 7, 1885.

The mining boom in BC led to many mines and smelters, mostly with American money. One of the world's largest smelters still exists in Trail. The jobs and money found in BC around the turn of the 20th century led to new towns like Nelson, Kimberley, and Rossland. A large coal mining business, run by Robert Dunsmuir and later his son James Dunsmuir, grew on Vancouver Island during this time.

As the mainland's economy improved with better transportation and more settlement, other resource industries grew. Throughout the late 1800s, fishing, forestry, and farming (including large orchards in the Okanagan region) became the main parts of the province's economy. This continued well into the late 1900s.

With the growing economy, old fur-trading posts became busy communities like Victoria, Nanaimo, and Kamloops. New communities also started, such as Yale, New Westminster, and later, Vancouver. Vancouver grew from smaller mill towns near the mouth of the Fraser River. It became a city in 1886 after being chosen as the end point for the Canadian Pacific Railway. Even after a huge fire almost destroyed the city three months later, Vancouver quickly became the largest city in the province. Its ports shipped British Columbia's resources and goods from the prairie provinces overseas. Vancouver is still the main city in the province, and the surrounding areas like Richmond, Burnaby, and Surrey have also grown a lot. As of 2016, Metro Vancouver is the third largest metropolitan area in Canada.

In the late 1800s, British Columbia's population became more diverse. People from China and Japan started moving to coastal settlements in the 1850s and even more in the 1880s. Immigrants from India also began arriving and helped develop the province's logging industry, creating towns like Paldi on Vancouver Island.

20th Century

Since the fur trade days, British Columbia's economy has relied on natural resources like fishing, logging, and mining. Large companies increasingly controlled these industries.

As industries grew and the economy boomed, more workers arrived, many from Asia and Europe. This mix of cultures brought strength but also sometimes conflict. The early 1900s was a time of big changes for immigrants and First Nations alike.

Workers' Rights Movement

With big businesses dominating the economy, a strong labour movement grew. Workers wanted better conditions and rights. The first major strike was in 1903 when railway workers went on strike against the CPR. A labour leader named Frank Rogers was killed during this strike, becoming an important figure for the movement. Canada's first general strike happened in 1918 after another labour leader, Ginger Goodwin, died at the Cumberland coal mines.

Tensions eased in the late 1920s but returned during the Great Depression. Many strikes in the 1930s were led by Communist Party organizers. A big strike happened in 1935 when unemployed men protested conditions in military-run relief camps. After two months of protests, the workers decided to take their complaints to the federal government. They started the On-to-Ottawa Trek, but their train was stopped, and the strikers were arrested.

World War II Contributions

During World War II, a Pacific Command was created in 1942 to defend the coast. Many coastal defenses were built, including harbor defenses for Vancouver. Today, the Museum of Anthropology at UBC stands on the foundation of old gun batteries that protected Vancouver Harbour.

Many soldiers from southern BC joined regiments that fought in Europe. The Rocky Mountain Rangers sent a battalion to fight the Japanese in the Battle of the Aleutian Islands in 1943. Thousands more British Columbians joined the Royal Canadian Navy and Royal Canadian Air Force. Two soldiers, Ernest Alvia Smith and John Keefer Mahony, received the Victoria Cross for their brave actions with BC-based regiments in Italy.

Columbia River Treaty

In 1961, British Columbia agreed to the Columbia River Treaty. This meant building three large dams in British Columbia. In return, the province received money because these dams helped produce hydroelectric power in the US. The dams flooded large areas in British Columbia but provided a very stable and clean source of power for the province.

21st Century

The 21st century has seen more harmony between different ethnic groups in British Columbia. In 2006, Prime Minister Stephen Harper apologized and offered compensation for the Chinese head tax that Chinese immigrants had to pay in the past.

Asian people are now the largest visible minority group in BC, making up over 20% of the population in 2006. Many cities in the Lower Mainland have large Chinese, South Asian, Japanese, Filipino, and Korean communities.

The province hosted the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver and Whistler.

First Nations

The history of First Nations people in BC is unique because, unlike many other parts of Canada, very few treaties were signed when settlers arrived. Most of the land was taken without treaties. Some early settlers thought that because First Nations populations had decreased due to diseases like smallpox, and due to racist beliefs, there was no need to deal with land questions.

When British Columbia joined Canada, the federal government became responsible for First Nations and their reserve lands. The province was responsible for other matters and resources. A commission in 1913 made some changes to lands but didn't address the important issues of land title and First Nations rights. First Nations groups sent delegations to Ottawa and London to seek justice, but often without success. Instead, the Indian Act, a federal law governing First Nations, was changed to make it a crime for them to organize or hire lawyers. Other unfair rules were also put in place, like the Potlatch Ban (which stopped important cultural ceremonies) and the growing Indian Residential School system, which aimed to force First Nations children to adopt European ways of life.

The situation of First Nations people in British Columbia has been a long-standing problem. They were often confined to small reserves that didn't provide enough economic opportunities. They received poor education and faced discrimination. For example, in many areas, they were not allowed in restaurants or other businesses. Status Indians gained the right to vote in 1960.

With a few exceptions, like the Douglas Treaties signed by Sir James Douglas around Victoria, no treaties were signed in British Columbia until 1998. Many Indigenous people wanted to negotiate treaties, but the province refused until 1990. A major legal decision in 1997, the Delgamuukw v. British Columbia case, confirmed that Aboriginal title (Indigenous land rights) still exists in British Columbia.

Today, many First Nations in BC are involved in the treaty process. However, there are disagreements about how these negotiations are handled. Some Indigenous people believe the current process is not fair and have chosen not to participate.

In May 2021, unmarked graves containing the remains of 215 children were found at a former Kamloops Indian Residential School. This discovery brought more attention to the painful history of the Canadian Indian residential school system.

Images for kids

-

Measha Brueggergosman performing at the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver.

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |