Kamloops Indian Residential School facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Kamloops Indian Residential School |

|

|---|---|

Kamloops Indian Residential School c. 1930.

|

|

| Location | |

|

Kamloops, British Columbia

Canada

|

|

| Coordinates | 50°40′47″N 120°17′43″W / 50.6796°N 120.2952°W |

| Information | |

| Former name | Kamloops Industrial School |

| Type | Canadian Indian residential school |

| Religious affiliation(s) | Catholic |

| Established | 1893 |

| Closed | 1978 |

| Authority | Catholic Church in Canada |

| Oversight | Crown–Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada |

| Principal |

|

| Gender | Coed |

| Enrolment | 500 |

| Language | English |

The Kamloops Indian Residential School was a large school in Kamloops, British Columbia. It was part of a system of schools called the Canadian Indian residential school system. These schools were set up to teach Indigenous children to live like Europeans. At its busiest in the 1950s, about 500 students attended the Kamloops school.

The school first opened in 1890. It was run by the Catholic Church until 1969, when the Canadian government took over. It finally closed in 1978. The school building is still standing today. It is located on the land of the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation.

In 2021, a special radar survey found signs of about 200 possible unmarked graves near the school. These findings need more investigation to be fully confirmed.

Contents

History of the School

The Kamloops Indian Residential School started as the Kamloops Industrial School in 1890. It became the Kamloops Indian Residential School in 1893. The main goal of these schools was to make Indigenous children adopt European ways of life.

The first buildings were three wooden structures. They had separate living areas for boys and girls, classrooms, and places for teachers.

Michel Hagan was the first principal. He left in 1892, and the Oblates of Mary Immaculate took over running the school. Father Alphonse-Marie Carion became principal in 1893. He believed that teaching students morals and religion was most important. He wanted to "civilize the Indians" and make them "useful and law-abiding members of society." He was principal until 1916.

Other principals included John Duplanil (starting 1927), James Fergus O'Grady (starting 1939), and G.P. Dunlop (starting 1958).

The school was built on the traditional land of the Secwepemc people. It continued to operate until 1978. After the government took over in 1969, it was used as a place for students to live while they attended other schools nearby.

In 1962, a Christmas film called Eyes of the Children was made at the school. It showed 400 students getting ready for Christmas.

Some people believed the school system failed because the Shuswap (Secwepemc) people kept their culture alive. However, others noted that the school system did change things. For example, English became the main language for the Shuswap Nation, and the future of the Shuswap language became uncertain.

The school building later became the first home of the Secwepemc Museum in 1982.

School Life and Challenges

Many children attended the school. After the 1920s, laws made it mandatory for children to attend. This meant many were taken from their homes. Students were not allowed to speak their native languages and were punished if they did. Children from many different First Nations communities in British Columbia and other provinces attended.

At one point, it was the largest residential school in Canada. Leonard Marchand, a Canadian politician, attended the school. So did George Manuel, a leader of the Secwépemc Nation. He remembered being hungry, having to speak English, and being called a "heathen" because of his grandfather.

In 1910, the principal said the government did not provide enough money to feed the students properly. In 1924, a fire destroyed the girls' part of the school. Forty students had to go outside in very cold weather with only their nightclothes on. A report in 1927 said that the poor buildings caused many illnesses like colds, bronchitis, and pneumonia. During the 1957–1958 influenza pandemic, half of the students at the school got sick.

In 2015, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada studied residential schools. They found that the schools caused "cultural genocide" for Indigenous peoples. They concluded that at least 4,100 students died while attending these schools. Many deaths were due to neglect, disease, and accidents. The report said it was impossible to know the total number of deaths.

European Dance Program

Starting in the 1940s, the school had a folk dancing program for girls. It only taught European dance styles, like Irish, Swiss, and Ukrainian dancing. Children were not allowed to learn Indigenous dances.

Dancers from the school performed at big events, like the Pacific National Exhibition in 1960. In 1964, girls from the school even traveled to Mexico to perform. People from the Canadian embassy called them "the finest ambassadors ever to come from Canada." The Knights of Columbus helped pay for the trip. The dance program ended in 1964 when the group leader left the school.

Students at the school often faced harsh treatment. They could be hit or shamed for small mistakes.

Possible Unmarked Graves

In 2021, Dr. Sarah Beaulieu, an expert in finding historical grave sites, used ground-penetrating radar to survey the area around the school. She found "disruptions in the ground" that looked like about 200 unmarked graves. She said these were "probable burials" or "targets of interest." Only digging up the area (excavation) can confirm if they are human remains.

The Indigenous community had long believed there were unmarked graves at the school, but there was no proof. Kukpi7 (Chief) Rosanne Casimir of Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc (TteS) said they were looking for records to help. The National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation has officially recorded 51 students who died at the school between 1919 and 1971.

Dr. Beaulieu noted that her survey only covered a small part of the school's large property. This means there could be other possible burial sites.

A year after the announcement, no digging had happened. In May 2022, Chief Casimir said a team of experts was formed to plan an archaeological dig. However, some survivors of the school have different ideas. Some want the remains to be properly buried, while others want the site to be left untouched. The RCMP "E" Division (police) said they were ready to help if needed, but the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation was leading the work.

As of January 2022, no remains had been dug up, so the initial findings are still being investigated.

Public Reactions

Many people reacted with sadness and shock to the news of the possible graves. Chief Rosanne Casimir called it "an unthinkable loss." The CEO of the First Nations Health Authority, Richard Jock, said it was "sadly not a surprise" and showed the lasting harm of the residential school system.

Leaders like British Columbia Premier John Horgan and Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau expressed their sorrow. Trudeau ordered flags on federal buildings to be flown at half-mast to honor the children. Many cities and provinces also lowered their flags. Some institutions lowered flags for 215 hours, one hour for each child.

The Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation thanked the government for their support but also asked for more action and responsibility from the Canadian government and the Catholic Church. Angela White, from the Indian Residential School Survivors Society, said that "reconciliation does not mean anything if there is no action."

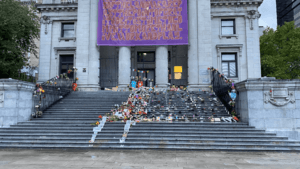

The news led to many community memorials across Canada. People placed 215 pairs of children's shoes in front of government buildings and churches. There were also calls for people to wear orange or place teddy bears on their porches to show support.

The University of British Columbia reviewed an honorary degree given to James Fergus O'Grady, a former principal of the Kamloops school. He was known for strict rules and harsh punishments.

On June 2, 2021, Archbishop of Vancouver J. Michael Miller said the Catholic Church would help identify the children who died.

On June 4, 2021, nine human rights experts from the United Nations asked Canada and the Catholic Church to fully investigate the deaths. They called for forensic exams and identification of the missing children. On June 6, Pope Francis spoke about the discovery, saying it "increases the awareness of the sorrows and sufferings of the past." He asked political and religious leaders to work together for healing.

In response, the Government of Ontario promised $10 million to search for unmarked graves at residential schools in Ontario. Many Canada Day celebrations were changed or cancelled to focus on reconciliation. A poll in June 2021 showed that most Canadians were aware of the reports from Kamloops.

On June 22, 2021, the Chinese government raised concerns about human rights violations against Indigenous people in Canada at the UN Human Rights Council. Prime Minister Trudeau responded by saying Canada had a Truth and Reconciliation Commission, unlike China.

Images for kids