Great Sioux Reservation facts for kids

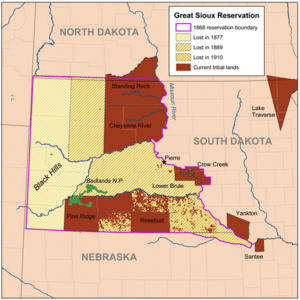

The Great Sioux Reservation was a large area of land set aside for the Lakota Sioux in the western parts of what are now South Dakota and Nebraska. This land was given to the Lakota, who were the main Native American group living there, through an agreement called the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868.

This huge reservation covered all of western South Dakota, often called "West River South Dakota," and a part of modern Boyd County, Nebraska. It was meant to be a home for the Lakota, also known as the Teton Sioux, who were seven important groups within the larger Great Sioux Nation.

Today, many Sioux people live on smaller reservations in states like Minnesota, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Montana. In the 1860s and 1870s, there were many conflicts between the United States and the Sioux. This happened as more American settlers moved west, taking over lands where the Sioux lived and hunted.

Contents

What Was the Great Sioux Reservation?

Besides the main reservation land, the 1868 treaty also allowed the Sioux to hunt and travel in other areas. These "unceded" territories included large parts of Wyoming and the Sandhills and Panhandle regions of modern Nebraska. Since different Lakota groups had their own areas, the United States set up several agencies. These agencies, run by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, were meant to manage the Lakota people across this vast region.

The Missouri River formed the eastern edge of the Great Sioux Reservation. However, some land within this boundary had already been given to other tribes, like the Ponca. The Lakota people believed the West River area was very important to them. They had lived there since finding the Paha Sapa, or Black Hills, in 1765. They became the main group in the area after defeating the Cheyenne in 1776. The Black Hills were sacred to the Lakota, who saw them as their ancient homeland.

Gold Discovery and Conflict

In 1874, a military expedition led by General Custer explored the Black Hills. This expedition, which started near Bismarck, Dakota Territory, discovered gold in the Paha Sapa. When this news spread, many miners rushed to the area. This led to serious fighting between the miners and the Lakota. The U.S. Army eventually defeated the Lakota in what became known as the Black Hills War.

After this war, a new treaty was signed in 1877. This treaty forced the Sioux to give up a strip of land about 50 miles (80 km) wide along the western border of Dakota Territory. They also lost all land west of the Cheyenne and Belle Fourche rivers, which included all of the Black Hills in modern South Dakota. Even after these changes, most of the Sioux reservation remained largely the same for another 13 years.

Changes to the Reservation Lands

In 1887, the United States Congress passed a law called the Dawes Act, also known as the General Allotment Act. This law aimed to break up the shared tribal lands on reservations. Instead, it gave 160-acre plots to individual families. The idea was to encourage Native Americans to become farmers, like European-American settlers. However, this plan often failed because the plots were too small for successful farming in the dry conditions of the Great Plains.

Just before North Dakota and South Dakota became states in November 1889, Congress passed another important law on March 2, 1889. This law divided the large Great Sioux Reservation into five smaller reservations:

- Standing Rock Reservation: This reservation included land in modern North Dakota that wasn't part of the original Great Sioux Reservation. Its main office was at Fort Yates.

- Cheyenne River Reservation: Its first office was west of the Missouri River. It later moved to Eagle Butte, South Dakota, after the Oahe Reservoir was built.

- Lower Brule Indian Reservation: Its office was near Fort Thompson.

- Rosebud Indian Reservation: This was also called the Upper Brule Reservation. Its office was near Mission, South Dakota.

- Pine Ridge Reservation: This was for the Oglala Lakota Sioux. Its office was at Pine Ridge, South Dakota, close to the Nebraska border.

It's important to know that the Crow Creek Indian Reservation, east of the Missouri River, and the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation, in North Dakota, were not part of the original Great Sioux Reservation.

After these five smaller reservations were created, the government opened up about 9 million acres (36,000 km2) of the former Great Sioux Reservation. This was about half of the original land. This land was then sold to the public for ranching and homesteading. Many people didn't settle there until the 1910s, after a new law allowed larger land allocations (320 acres (1.3 km2)) for what was known as "semi-arid land."

Railroads encouraged settlement, and the U.S. government even published incorrect advice on how to farm the dry land. Many new immigrants to the United States moved to the area. The Lakota tribes received $1.25 per acre for the land. This money was usually used to help pay for the government's treaty promises to the tribes.

The Dawes Act and Land Loss

The Dawes Act was meant to change how Native Americans lived. The government wanted to break up the shared tribal lands and give individual plots to families. This was supposed to make them live like European-American farmers. Government officials recorded tribal members and gave land to the heads of families. Any land left over was called "surplus" and sold to non-Native people. This caused a huge loss of shared tribal lands. After a certain time, Native Americans could also sell their individual plots, and many did.

These changes, along with other actions, greatly reduced the total land owned by Native Americans. The government tried to force them to become farmers and craftsmen. However, the land allocations were not based on real knowledge of whether the dry lands could support the small family farms the government imagined. This experiment largely failed for both the Lakota and most of the new settlers.

Many European immigrants settled on the newly available lands. Some "experts" even suggested that regularly tilling the soil would "attract" moisture from the sky. The Plains were settled during a time that was wetter than usual, so farmers had some early success. But when normal dry conditions returned, many farms failed. Farmers didn't know how to keep the limited moisture in the soil. Their farming methods led to the terrible Dust Bowl conditions of the 1930s. Huge dust clouds reached far-off cities, and much of the fertile topsoil was lost. Many farmers had to abandon their land. Today, most farming is done by large industrial farms using different methods, like winter planting for wheat.

By the 1960s, the five reservations had lost much of their land. Some land was sold after the allotment process. Also, the United States took land for federal water projects, like building Lake Oahe and other dams on the Missouri River. For example, the Rosebud Reservation, which once included parts of five counties, was reduced to just one county: Todd County. Similar reductions happened to the other reservations.

Both inside and outside the reservation areas in West River, the Lakota people are a very important part of the region's history. Many towns have Lakota names, such as Owanka, Wasta, and Oacoma. Other towns, like Hot Springs and Spearfish, have English names that were translated from original Lakota names. Some rivers and mountains still have Lakota names. The buffalo and antelope, which were important food sources for the Lakota, now graze alongside cattle and sheep. Raising bison has become more common on the Great Plains, helping to bring back this important animal. Many monuments in the area honor both Lakota and European-American heroes and events.

Land Claims and Justice

During the Dust Bowl of the 1930s, many non-Native farms were abandoned. Instead of giving this land back to the Sioux, the federal government gave much of it to federal agencies. For example, the National Park Service took over parts of what are now National Grasslands. The Bureau of Land Management was given other lands to manage.

In some cases, the United States took even more land from the smaller reservations. An example is the WWII-era Badlands Bombing Range, which was taken from the Oglala Sioux of Pine Ridge. Even though the U.S. Air Force said they didn't need the range anymore in the 1960s, it was given to the National Park Service instead of being returned to the tribe.

Because the Lakota consider the Black Hills sacred and believe the land was taken illegally, they sued the U.S. government in the 20th century to get it back. In 1980, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled in the case United States v. Sioux Nation of Indians that the land had indeed been taken illegally. The U.S. government offered money as a settlement. However, the Oglala Lakota are still asking for the land to be returned to their nation. The money from the settlement is currently earning interest in an account.

| James B. Knighten |

| Azellia White |

| Willa Brown |