Black Elk facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Black Elk

Heȟáka Sápa |

|

|---|---|

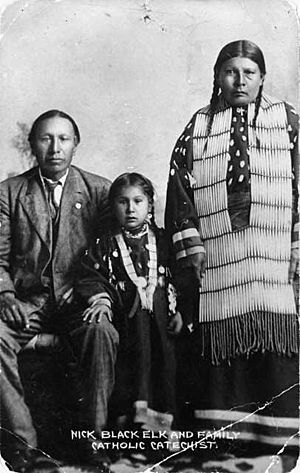

Nicholas Black Elk, daughter Lucy Black Elk and wife Anna Brings White, photographed ca 1910.

|

|

| Born | 1 December 1863 Little Powder River, Wyoming, United States

|

| Died | 19 August 1950 (aged 86) Pine Ridge, South Dakota, United States

|

| Resting place | Saint Agnes Catholic Cemetery, Manderson, South Dakota |

| Occupation | Catechist |

| Children | Ben Black Elk |

| Servant of God Nicholas Black Elk |

|

|---|---|

| Patronage | Native Americans |

Heȟáka Sápa, known as Black Elk (born December 1, 1863 – died August 19, 1950), was a very important spiritual leader. He was a wičháša wakȟáŋ (a "medicine man" or "holy man") and a heyoka (a sacred clown) of the Oglala Lakota people.

Black Elk was a second cousin to the famous war leader Crazy Horse. He even fought alongside Crazy Horse in the Battle of the Little Bighorn. Later in his life, he survived the terrible Wounded Knee Massacre in 1890. He also traveled to Europe and performed in Buffalo Bill's Wild West show.

Black Elk is most famous for sharing his life story, visions, and religious beliefs. He told these stories to a poet named John Neihardt. Neihardt then wrote a book called Black Elk Speaks, published in 1932. This book has been read by many people who are interested in Native American religions. Black Elk also spoke to an ethnologist, Joseph Epes Brown, for his 1947 book The Sacred Pipe.

Later in his life, Black Elk became a Catholic and worked as a catechist, teaching about Christianity. However, he also continued to practice traditional Lakota ceremonies. The Roman Catholic Diocese of Rapid City began a process in 2016 to consider him for beatification (a step towards becoming a saint) in the Catholic Church. His grandson, George Looks Twice, said that Black Elk was comfortable praying with both his pipe and his rosary. He regularly took part in both Catholic Mass and Lakota ceremonies.

Contents

Early Life and Visions

Growing Up

Black Elk came from a family of healers and medicine men. Both his father and his uncles were medicine men. He was born into an Oglala Lakota family in December 1863. This was near the Little Powder River in what is now Wyoming. The Lakota people measured time using "Winter counts". According to their records, Black Elk was born "the Winter When the Four Crows Were Killed on Tongue River."

His Great Vision

When Black Elk was nine years old, he became very sick. He said he lay still and unresponsive for several days. During this time, he experienced a powerful vision. He said he was visited by "Thunder Beings" (Wakinyan). He described these spirits as kind, loving, and wise, like respected grandfathers.

When he was 17, Black Elk told a medicine man, Black Road, all about his vision. Black Road and the other medicine men were amazed by how grand and important the vision was. Black Elk later told John Neihardt about this vision. In it, he saw a huge tree that represented the life of the earth and all people. Neihardt wrote about this special vision in Black Elk Speaks.

In one part of his vision, Black Elk said he was taken to the center of the earth. He also saw the central mountain of the world. He described seeing "the shapes of all things in the spirit." He understood how "all shapes must live together like one being." He also saw that "the sacred hoop of my people was one of many hoops that made one circle." This circle was "wide as daylight and as starlight." In its center grew "one mighty flowering tree to shelter all the children of one mother and one father." He felt that this vision was truly holy.

The Battle of the Little Bighorn

Black Elk was present at the famous Battle of the Little Bighorn.

Later Years: Travels and the Ghost Dance

Touring with Buffalo Bill's Wild West

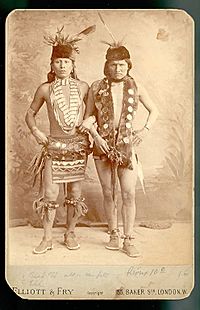

In 1887, Black Elk traveled to England with Buffalo Bill's Wild West show. He described this experience in his book. On May 11, 1887, the show performed for Queen Victoria. They called her "Grandmother England." Black Elk was also there for her golden jubilee celebration.

In the spring of 1888, the Buffalo Bill's Wild West show sailed back to the United States. Black Elk got separated from the group. The ship left without him and three other Lakota performers. They then joined another wild west show. He spent the next year touring in Germany, France, and Italy. When Buffalo Bill arrived in Paris in May 1889, Black Elk got a ticket to go home. He arrived back at Pine Ridge in the autumn of 1889. During his time in Europe, Black Elk had a chance to learn about the "white man's way of life." He also learned to speak some basic English.

The Ghost Dance and Wounded Knee

After touring, Black Elk returned to the Pine Ridge Reservation. He became involved with the Ghost Dance movement. He brought a special Ghost Dance shirt to its followers. He had seen his ancestors in a vision who told him, "We will give you something that you shall carry back to your people." They said, "with it they shall come to see their loved ones."

The Ghost Dance gave people hope. They believed that white settlers would soon leave. They hoped the buffalo herds would return. People also believed they would be reunited with loved ones who had passed away. They dreamed of the old way of life returning before the white settlers arrived. This was not just a religious movement. It was also a way to respond to the loss of their culture.

Black Elk was present at the Wounded Knee Massacre in 1890. This tragic event happened because US settlers feared the growing interest in the Ghost Dance among Plains tribes. Black Elk said he rode on horseback and helped rescue some wounded people. He arrived after many of Spotted Elk's (Big Foot's) people had been shot. A bullet grazed his hip. The Lakota leader Red Cloud convinced him to stop fighting after he was wounded. Black Elk then stayed on the Pine Ridge Reservation.

Later Life: Becoming Catholic

Starting around 1934, Black Elk returned to performing. He organized an Indian show at the Sitting Bull Crystal Cavern Dance Pavilion. This was in the sacred Black Hills. Unlike the Wild West shows that focused on warfare, Black Elk created a show to teach visitors about Lakota culture. It also showed traditional sacred rituals, like the Sun Dance.

Black Elk's first wife, Katie, became a Roman Catholic. Their three children were also baptized as Catholics. After Katie died in 1903, Black Elk himself became Catholic in 1904, when he was in his 40s. He was given the Christian name Nicholas. He later became a catechist, teaching others about Christianity.

He married again in 1905 to Anna Brings White, who was a widow with two daughters. Together, they had three more children. These children were also baptized and raised as Catholic. Black Elk said his children "had to live in this world." Other medicine men, like his nephew Fools Crow, called him both Black Elk and Nicholas Black Elk. His son, Benjamin Black Elk (1899–1973), became famous as the "Fifth Face of Mount Rushmore". He posed for tourists at the memorial in the 1950s and 1960s.

Sharing His Stories

In the early 1930s, Black Elk shared his stories with John Neihardt and Joseph Epes Brown. This led to the books being published. His son, Ben, helped by translating Black Elk's stories into English. Neihardt's daughter, Enid, wrote down these accounts. She later put them in order for Neihardt to use. So, many people were involved in recording Black Elk's stories.

After Black Elk spoke with Neihardt, Neihardt asked why Black Elk had "put aside" his old religion. He also asked why he baptized his children. Neihardt's daughter, Hilda, said Black Elk replied, "My children had to live in this world." For Black Elk, "To live" was a very important prayer in Lakota spirituality. He mentioned this prayer for life many times in The Sacred Pipe. Hilda Neihardt wrote in her 1995 memoir that just before he died, Black Elk told his daughter Lucy Looks Twice, "The only thing I really believe is the pipe religion."

Black Elk's Legacy

Since the 1970s, the book Black Elk Speaks has become very popular. Many people interested in Native Americans in the United States have read it. With the rise of Native American activism, more people became interested in Native American religions. The book was especially popular among those who were new to traditional Native American culture.

However, some people have said that John Neihardt, as the author, might have changed or added some parts of the story. They suggest he might have done this to make the book more appealing to white readers in the 1930s. Or, perhaps he did not fully understand the Lakota culture.

On August 11, 2016, a mountain in South Dakota was officially renamed Black Elk Peak. It was formerly called Harney Peak. This renaming honored Nicholas Black Elk and recognized the mountain's importance to Native Americans.

In August 2016, the Roman Catholic Diocese of Rapid City began the official process for Black Elk's beatification in the Catholic Church. On October 21, 2017, the process for his canonization (becoming a saint) was formally opened. This means the Catholic Church is investigating his life and works. Black Elk's decision to become Catholic has puzzled some people, both Indigenous and Catholic. Biographer Jon M. Sweeney explained in 2020 that Black Elk "didn't see reason to disconnect from his vision life after converting to Catholicism." Sweeney added, "Was Black Elk a true Lakota in the second half of his life? Yes.... Was he also a real Christian? Yes." He is now called a "Servant of God" by Catholics. This title means his life is being studied for possible sainthood. His efforts to share the Christian faith with both Native and non-Native people were noted. His ability to blend his faith with Lakota culture was also highlighted.

Books by or about Black Elk

- Books of Black Elk's accounts

- Black Elk Speaks: Being the Life Story of a Holy Man of the Oglala Sioux (as told to John G. Neihardt), Bison Books, 2004 (originally published in 1932) : Black Elk Speaks

- The Sixth Grandfather: Black Elk's Teachings Given to John G. Neihardt, edited by Raymond J. DeMallie, University of Nebraska Press; new edition, 1985. ISBN: 0-8032-1664-5.

- The Sacred Pipe: Black Elk's Account of the Seven Rites of the Oglala Sioux (as told to Joseph Epes Brown), MJF Books, 1997

- Spiritual Legacy of the American Indian (as told to Joseph Epes Brown), World Wisdom, 2007

- Books about Black Elk

- Nicholas Black Elk: Medicine Man, Catechist, Saint, by Jon M. Sweeney, Liturgical Press. ISBN: 978-0-8146-4416-4

- Black Elk: Holy Man of the Oglala, by Michael F. Steltenkamp, University of Oklahoma Press; 1993 ISBN: 0-8061-2541-1

- Nicholas Black Elk: Medicine Man, Missionary, Mystic, by Michael F. Steltenkamp, University of Oklahoma Press; 2009. ISBN: 0-8061-4063-1

- The Sixth Grandfather: Black Elk's Teachings Given to John G. Neihardt, edited by Raymond J. DeMallie; 1985

- Black Elk and Flaming Rainbow: Personal Memories of the Lakota Holy Man, by Hilda Neihardt, University of Nebraska Press, 2006. ISBN: 0-8032-8376-8

- Black Elk's Religion: The Sun Dance and Lakota Catholicism, by Clyde Holler, Syracuse University Press; 1995

- Black Elk: Colonialism and Lakota Catholicism, by Damian Costello, Orbis Books; 2005

- Black Elk Reader, edited by Clyde Holler, Syracuse University Press; 2000

- Black Elk, Lakota Visionary, by Harry Oldmeadow, World Wisdom; 2018

Film

In 2020, a documentary called Walking the Good Red Road – Nicholas Black Elk's Journey to Sainthood was shown on ABC television. It was produced by the Diocese of Rapid City. You can watch it on Vimeo.

See also

In Spanish: Alce Negro para niños

In Spanish: Alce Negro para niños

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |