Show Indians facts for kids

Show Indians were Native American performers who worked in Wild West shows. The most famous of these was Buffalo Bill's Wild West. Most of these performers were Oglala Lakota people from the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota.

These performers acted in shows that recreated historical battles. They also showed off their amazing horse-riding skills and performed traditional dances for audiences. Many Native American veterans from the Great Plains Wars joined these shows. This happened at a time when the government's Office of Indian Affairs wanted Native Americans to adopt American ways of life. Many "Show Indians" later became actors in early silent films.

Contents

The Wild West and Native Americans

When people think of the American West, they often imagine Native Americans. Especially the northern Great Plains tribes, who lived in tipis, were great horse riders, and hunted bison.

William Frederick "Buffalo Bill" Cody helped shape this image with his Wild West shows. His show traveled across the United States and Europe from 1883 to 1913. Native Americans were part of the show from the very beginning. At first, performers came from the Pawnee tribe (1883–1885), and later from the Lakota tribe.

The name "Show Indians" probably started with newspaper writers around 1891. By 1893, the Office of Indian Affairs often used this term. It showed that these Native performers had a special job. The Native performers themselves called themselves oskate wicasa, which means "show man."

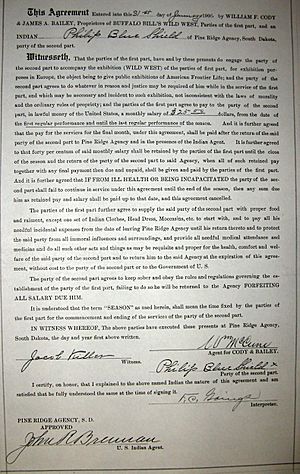

Hiring Performers

Hundreds of Native Americans worked for the show between 1883 and 1917. They were hired for each season and paid for their time. Recruiting often happened in Rushville, Nebraska, near the Pine Ridge Agency.

Native Americans were very important to the Wild West shows from the start. In the first show in 1883 in Omaha, Nebraska, six out of twelve acts, including the opening parade, featured Native American performers.

In 1885, Colonel Cody started hiring more from the Pine Ridge Agency. This was after he hired the famous Hunkpapa Lakota Sioux leader, Sitting Bull. Sitting Bull was known as the last Native American to give up to the government during the American Indian Wars. He joined the show in Buffalo, New York, on June 12, 1885.

Even though Sitting Bull only toured for one season, his involvement changed things. After him, the Lakota became the main "Show Indians." The Lakota were known as strong warriors, which fit the image of Native Americans that people in America and Europe had. Using real Native performers, instead of actors, showed how much people were interested in Native cultures at that time.

What They Performed

Show Indians did many different acts in the Wild West shows. They showed off their amazing horse riding, their skills with bows and arrows, and their beautiful dances.

The most popular acts were historical re-enactments. Performers would recreate events from the recent past. Shows included Native American attacks on settlers' cabins, stagecoaches, pony-express riders, and wagon trains.

From 1885 to 1898, Buffalo Bill's shows also re-enacted the Battle of the Little Bighorn and the death of George Armstrong Custer. After 1890, they even re-enacted the Wounded Knee Massacre.

These performances gave Native Americans a way to continue their cultural practices. Many of these practices were not allowed on Indian reservations. Vine Deloria, Jr. noted that the first "Show Indians" were "playing" Indian as a way to keep their culture alive. He wrote that maybe they felt that even a show version of their traditions was better than losing their culture completely. The Wild West shows gave them a place to be Native American and avoid problems from missionaries or government agents for many years.

Disagreements Over Hiring Native Americans

Some groups, like the Indian Rights Association and the Office of Indian Affairs, did not like the hiring of Native American performers. They had several reasons for their concerns.

Some groups worried that many Native Americans died while working for the shows. They claimed that show promoters treated them badly or took advantage of them. These groups believed that Native American cultures needed to change through land ownership, education, and work. They thought that if Native Americans adopted new ways of life, they would become more "civilized."

The Office of Indian Affairs was concerned about how the shows affected their policies. They wanted Native Americans to adopt American customs. The main disagreement between the government and show promoters was about which image of Native Americans would be seen by the public.

In 1886, the Office of Indian Affairs started to control the hiring of Native American performers. By 1889, they required Native Americans to sign individual contracts with the shows. These contracts had to be watched by Office of Indian Affairs agents. Only after these rules were met would the commissioner allow Native Americans to leave the reservation. The Office of Indian Affairs was especially worried about Native Americans working in shows that were not approved. They feared this could lead to poor health and bad behavior among the performers.

Thomas Jefferson Morgan, who became commissioner in 1889, was very critical of Native American employment in Wild West shows. He publicly criticized the shows for not keeping their promises in contracts. When new contracts came in, he often rejected them or added rules that the shows could not meet. This stopped Native Americans from joining those shows. Morgan also warned Native American performers that they could lose their land, payments, and tribal status if they joined. He also threatened show promoters with losing their money if they did not follow their contracts. Morgan's goal was for Native Americans to quit the shows.

In 1890, two Native Americans named "No Neck" and "Black Heart" spoke at an inquiry by the Office of Indian Affairs. This meeting looked into whether it was right for Native Americans to work in show business. The acting commissioner, A.C. Belt, said, "It is not considered among white people a very helpful or elevating business." He added that what was not good for white people was not good for Native Americans.

However, the Native Americans strongly defended their work. They turned the inquiry into a criticism of the Office of Indian Affairs' own policies. They compared their lives in the show to their lives on the Pine Ridge Agency. Their comparison made the Office of Indian Affairs look bad.

Rocky Bear explained that he had helped the government by supporting reservations. He said he was well-fed in the show, "that is why I am getting so fat," he said, touching his cheeks. He added that he only got "poor" when he returned to the reservation. He said he would stop performing if the "Great White Father" wanted him to, but until then, "that is the way I get money." He then showed them a purse with $300 in gold coins, saying he saved it for his children's clothes. This silenced the officials.

Black Heart also denied claims of mistreatment. He said, "We were raised on horseback; that is the way we had to work." He added that Buffalo Bill Cody and Nate Salsbury "furnished us the same work we were raised to; that is the reason we want to work for these kind of men."

Traveling with Buffalo Bill

Many of the "Show Indians" were Oglala Sioux from the Pine Ridge Agency. They liked the chance to travel with Colonel Cody. Native American performers and their families could be free for six months each year. This was a break from the strict rules of government reservations. On reservations, they were not allowed to wear tribal clothes, hunt, or dance.

Colonel Cody treated Native American performers well. They received wages, food, transportation, and places to live while away from home. Show Indians were allowed to wear traditional clothing, which was forbidden on the reservation. They lived in the Wild West's tipi "village" when the weather was good. Visitors could walk through this village and meet the performers.

When not performing, Native Americans could travel freely by car or train. They could go sightseeing or visit friends. Interpreters helped translate for the Native American performers both inside and outside the Wild West camp.

Show Indians agreed to follow the rules of the Wild West Company. Indian Police were organized to make sure the rules were followed. The number of police depended on how many Native Americans were with the show each season. Usually, there was one policeman for every twelve Native Americans. Indian policemen were chosen from the performers. They were given badges and paid $10 more per month. Chiefs Iron Tail and Short Man were leaders of the Indian Police in 1898. Most of these Indian Police were former U.S. Army Indian Scouts.

Besides performing in the United States, Show Indians also toured Europe. Their first international trip was to London, England, on March 31, 1887. On the ship State of Nebraska, the show's group included 97 Native Americans, 18 buffalos, and many other animals and people. The show was part of the celebration for Queen Victoria's Golden Jubilee. They toured through Birmingham, Salford, and London for five months. The show returned to Europe in 1889-1890, visiting England, France, Italy, and Germany.

World's Fairs and Big Shows

In 1893, William F. Cody brought his Wild West show to the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago. The Bureau of Indian Affairs was supposed to help with an American Indian Exhibit at the Exposition. This exhibit included a model Indian school and an Indian camp. However, due to money problems, the Bureau of Indian Affairs pulled out.

Even though he was not part of the official World's Fair, William F. Cody set up his own show. He used a 14-acre area near the fair's main entrance for "Buffalo Bill's Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders of the World." He built stands around an arena that could hold 18,000 people.

Seventy-four Native Americans from Pine Ridge Reservation, who had just returned from a European tour, were hired to perform. Cody also brought 100 more Lakota people from Pine Ridge, Standing Rock, and Rosebud reservations. They visited the fair at his expense and took part in the opening ceremonies. Over two million people saw Buffalo Bill's show in Chicago. Many people thought it was part of the World's Fair itself.

How the Wild West Was Shown

The popular idea of Native Americans living in tribes, sleeping in tipis, wearing feather headdresses, riding horses, and hunting bison came largely from the Great Plains tribes. These tribes were the main source of Native American performers. The idea of the Sioux as the typical American Indian started with early dime novels. Then, the Wild West shows kept that image alive, and it continued through movies, radio, and television westerns. Historian Robert F. Berkhofer, Jr. called the Wild West shows "dime novels come alive."

The Wild West shows aimed to celebrate American progress. They wanted to show how great American history and society were. The American West was seen as a key part of what made America special. According to Frederick Jackson Turner's famous idea, the frontier was a place that created a unique American spirit. This spirit was about being independent and self-reliant.

Nate Salsbury, Cody's partner, said the shows truly showed frontier life. He saw the show as a national story that represented the "true" West. Joy Kasson noted that people often thought the entertainment was "the real thing." Buffalo Bill's Wild West became known as America's Wild West. In Cody's stories of the West, Native Americans played a very important role.

Buffalo Bill and Gertrude Käsebier

Gertrude Käsebier was a very important American photographer in the early 1900s. She was known for her pictures of mothers, her strong portraits of Native Americans, and for encouraging women to become photographers.

In 1898, Käsebier saw Buffalo Bill's Wild West group parade past her studio in New York City. They were on their way to Madison Square Garden. She remembered her respect for the Lakota people. This inspired her to write to William "Buffalo Bill" Cody. She asked for permission to photograph members of the Sioux tribe from the show in her studio.

Cody and Käsebier both deeply respected Native American culture. They were friends with the Sioux. Cody quickly said yes to Käsebier's request. She started her project on Sunday, April 14, 1898. Käsebier's project was purely artistic. Her photos were not for selling or for Buffalo Bill's show booklets. Käsebier took classic photos of the Sioux when they were relaxed. Chief Iron Tail and Chief Flying Hawk were among her most powerful and revealing portraits. Käsebier's photographs are kept at the National Museum of American History at the Smithsonian Institution.

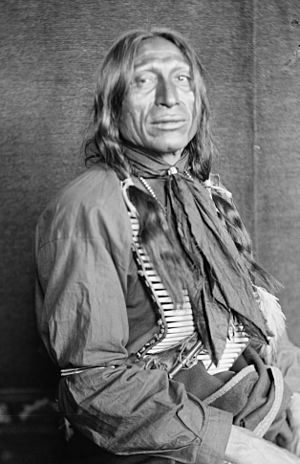

Chief Iron Tail

Käsebier's session with Chief Iron Tail is her only recorded story. Before visiting Käsebier’s studio, the Sioux at Buffalo Bill's Wild West Camp gathered. They shared their best clothing and accessories with those chosen to be photographed.

Käsebier admired their effort. But she wanted to photograph a "real raw Indian, the kind I used to see when I was a child." She was thinking of her early years in Colorado and on the Great Plains. Käsebier chose Chief Iron Tail to photograph without his fancy clothes. He did not mind.

The photo she took was exactly what Käsebier wanted. It was a relaxed, quiet, and beautiful picture of the man. He was without decorations, showing himself to her and the camera openly.

Several days later, Chief Iron Tail was given the photograph. He immediately tore it up, saying it was too dark. Käsebier photographed him again, this time in his full feather headdress. He was very happy with this one. Chief Iron Tail was famous around the world. He appeared as the lead with Buffalo Bill at the Champs-Élysées in Paris, France, and the Colosseum in Rome. Chief Iron Tail was a superb showman. He did not like the relaxed photo of himself. But Käsebier chose it as the main picture for an Everybody’s Magazine article in 1901.

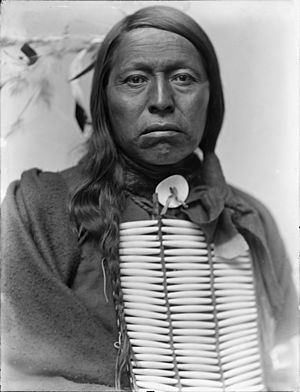

Chief Flying Hawk

Chief Flying Hawk's intense stare is the most striking of Käsebier's portraits. Other Native Americans could relax, smile, or pose nobly. Chief Flying Hawk had fought in almost all the battles against United States troops during the Great Sioux War of 1876. He fought with his cousin Crazy Horse and his brothers Kicking Bear and Black Fox II in the Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876. He was also present when Crazy Horse died in 1877 and at the Wounded Knee Massacre in 1890.

In 1898, Chief Flying Hawk was new to show business. He could not hide his anger and frustration. He was imitating battle scenes from the Great Plains Wars for Buffalo Bill's Wild West. He did this to escape the difficulties and poverty of the Indian reservation. Soon, though, Chief Flying Hawk learned to appreciate the benefits of being a "Show Indian" with Buffalo Bill's Wild West.

Chief Flying Hawk often walked around the show grounds in his full traditional clothing. He sold his "cast card" postcards for a penny. This helped promote the show and added to his small income. After Chief Iron Tail died on May 28, 1916, Chief Flying Hawk was chosen by all the Native American performers to be the new head Chief. He then led the grand processions as the main Chief of the Indians.

Famous Show Indians

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |