Fetterman Fight facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Fetterman Fight |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Red Cloud's War and the Sioux Wars | |||||||

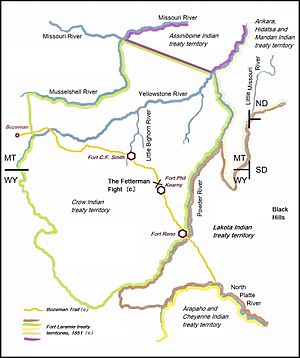

The Bozeman trail and the location of the Fetterman Fight |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Lakota Cheyenne Arapaho |

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Red Cloud High Backbone (Hump) Crazy Horse Man Afraid Of His Horses |

|||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 81 | 1,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 81 killed | Between 13 and 60 killed | ||||||

The Fetterman Fight was a major battle during Red Cloud's War. It happened on December 21, 1866. This fight was between a group of Native American tribes and the United States Army. The Native American side included the Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho tribes. The U.S. Army soldiers were from Fort Phil Kearny in Wyoming.

The U.S. military's main goal was to protect people traveling on the Bozeman Trail. This trail was a path for settlers heading west. A small group of ten Native American warriors, including Crazy Horse, used a trick. They pretended to run away to lead U.S. soldiers into a trap. All 81 soldiers, led by Captain William J. Fetterman, were killed in the ambush. At that time, it was the worst defeat the U.S. Army had ever faced on the Great Plains. The Native American alliance won the battle. After this, the remaining U.S. forces left the area.

Contents

Why the Fight Happened

The land where the Fetterman Fight took place was originally for the Crow Indian tribe. This was agreed upon in the Treaty of Fort Laramie (1851) in 1851. The Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho tribes had accepted this treaty. However, they soon started hunting buffalo outside their agreed areas. They moved into Crow land because buffalo herds were shrinking. By 1860, these tribes, who were old enemies of the Crow, had taken over the Crow's hunting grounds. This area was west of the Powder River.

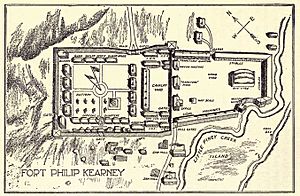

In June 1866, Colonel Henry B. Carrington led his soldiers into the Powder River country. This was now the hunting ground for the Lakota, Northern Cheyenne, and Northern Arapaho. His orders were to protect settlers traveling along the Bozeman Trail. Carrington had about 700 soldiers and 300 civilians with him. He built three forts along the trail. His main fort was Fort Phil Kearny, near what is now Buffalo, Wyoming. All three forts were in Crow territory. The army said they had a right to build "roads, military and other post" based on a treaty. About 400 of his soldiers and most civilians stayed at Fort Kearny.

Early Conflicts and Challenges

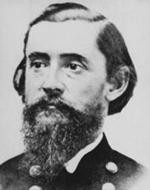

While Fort Kearny was being built, Native American warriors attacked about 50 times. Colonel Carrington lost over 20 soldiers and civilians. The warriors were usually on horseback and came in groups of 20 to 100. Some of Carrington's younger officers wanted to attack the Native Americans. Their desire grew stronger after November 3, when 63 cavalry soldiers arrived. Lieutenant Horatio S. Bingham led these cavalrymen. Captains William J. Fetterman and James W. Powell also joined from Fort Laramie. Fetterman was a Civil War hero.

Even though he had no experience fighting Native Americans, Fetterman thought Carrington was too careful. He reportedly boasted, "Give me 80 men and I can ride through the whole Sioux nation." Many other officers felt the same way. Carrington let Fetterman try a night ambush, but the Native Americans saw it coming. They instead stampeded cattle away from Fetterman's trap. On November 22, Fetterman himself almost fell into a trap. He was guarding a wagon train collecting wood. A single Native American tried to trick the soldiers into chasing him. The wagon train leader, Lieutenant Bisbee, wisely stayed put.

Carrington's Plan and Caution

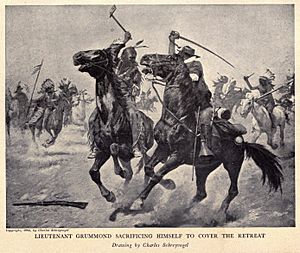

On November 25, 1866, General Philip St. George Cooke, Carrington's boss, ordered him to attack the Native Americans. Carrington's first chance came on December 6. A wood train was attacked four miles west of the fort. Carrington sent Fetterman with cavalry and infantry to help the wood train. Carrington led another group to try and cut off the Native Americans' escape. During this, Lieutenants Grummond and Bingham got separated from Carrington. Carrington was surrounded by about a hundred warriors. Fetterman arrived and helped Carrington, and the warriors left.

Bingham and a sergeant were later found dead. Four soldiers were wounded after chasing a Native American decoy into a trap. Carrington said he killed ten Native Americans. But both he and Fetterman realized their soldiers were not well-trained. Fetterman said, "This Indian war has become a hand-to-hand fight requiring the utmost caution." Carrington's guide, the famous mountain man Jim Bridger, said it simply: "These soldiers don't know anything about fighting Indians."

After this, Carrington trained his soldiers more. He doubled the guards for wood trains. He kept the fort's 50 horses ready from morning to night. On December 19, Native Americans attacked another wood train. Carrington sent Captain Powell, his most careful officer, to help. He gave clear orders not to chase the Native Americans beyond Lodge Trail Ridge. Powell followed orders and returned safely. Carrington reminded his soldiers to be careful until more help arrived. On December 20, Carrington refused Fetterman and Captain Brown's idea to lead 50 civilians to attack a Lakota village 50 miles away.

The Trap is Set

Red Cloud and other Native American leaders were encouraged by their successes. They decided to plan a big attack on Fort Kearny before winter snows forced them to split up. The decoy trick had worked before, so they decided to try it again. This time, they would have enough warriors to destroy any group of soldiers sent to chase them. More than 1,000 warriors gathered about 10 miles north of Fort Kearny. They chose a good spot for the trap along the Bozeman Trail, north of Lodge Trail Ridge. This spot was out of sight, but only about 4 miles from Fort Kearny. The Cheyenne and Arapaho hid on the west side of the trail. The Lakota hid on the east. The young Oglala warrior Crazy Horse was among the decoys.

The morning of December 21, 1866, was clear and cold. Around 10 am, Carrington sent a wagon train to get wood about 5 miles northwest of the fort. Almost 90 soldiers were sent to guard it. Less than an hour later, signals came that the wagon train was under attack. Carrington ordered a relief party of 49 infantrymen and 27 mounted soldiers. Captain James Powell was supposed to lead them. But Fetterman, being a higher-ranking officer, asked for and was given command. Powell stayed behind. Lieutenant George W. Grummond, another officer who criticized Carrington, led the cavalry. Captain Frederick Brown, also a critic, and two civilians, James Wheatley and Isaac Fisher, joined Fetterman. This made the relief force 81 men. The infantry marched first, and the cavalry followed.

Carrington said his orders were very clear. The relief party was "under no circumstances" to "pursue over the ridge, that is Lodge Trail Ridge." Lieutenant Grummond's wife wrote in her memoirs that Carrington gave these orders twice. She said everyone heard them. But after leaving the fort, Fetterman took the Lodge Ridge Trail north instead of the trail toward the wood train. Carrington thought Fetterman planned to attack the Native Americans from behind. Soon, the signal came that the wood train was no longer under attack. About 50 Native Americans appeared near Fort Kearny, but Carrington scared them off with cannon shots. These Native Americans and others bothered Fetterman as he climbed Lodge Trail Ridge. He then disappeared from the fort's view.

Around noon, Carrington and his men at the fort heard heavy gunfire to the north. Carrington gathered about 75 men under Captain Ten Eyck. He sent them on foot to find Fetterman. Ten Eyck moved carefully up Lodge Trail Ridge. When he reached the top, around 12:45 pm, he and his men saw many Native Americans in the Peno Creek valley below. Warriors came close and taunted the soldiers. Meanwhile, Carrington sent another group of 42 soldiers to join Ten Eyck. The Native Americans in the valley slowly left. Ten Eyck moved forward carefully. The soldiers found the bodies of Fetterman and all his men in the valley. That afternoon, wagons brought the bodies back to Fort Kearny.

Native American Perspective

Charles Eastman, a Native American writer, said that in 1866, Native Americans were very unhappy with white settlers. Red Cloud was determined to fight. He told his people, "When the Great Father in Washington sent us his chief soldier to ask for a path through our hunting grounds... we were told that they wished merely to pass through our country... Yet before the ashes of the council fire are cold, the Great Father is building his forts among us. His presence here is an insult and a threat... Dakotas, I am for war!"

Less than seven days after this speech, the Sioux went to Fort Phil Kearny. A big attack was planned. Many well-known Sioux chiefs agreed to fight the invaders. Crazy Horse led the attack, with older leaders giving advice. They were very successful. In less than half an hour, they defeated nearly 100 men under Captain Fetterman. Fetterman had been cleverly tricked out of the fort.

The Battle's Name and Prophecy

Before the battle, Red Cloud asked for advice from a special spiritual leader. This leader was believed to have special powers. He rode his pony four times between the warriors and Lodge Trail Ridge. Each time, he seemed to gather more "soldiers" into his hands. When he returned the fourth time, he said he had 100 blue-coat soldiers in each hand. The Lakota saw this as a good sign that they would win. They later called the battle the "Battle of the Hundred-in-the-Hands." A total of 81 American soldiers and civilians died in the battle.

The Battle Unfolds

The battlefield was quickly checked, and the bodies of the soldiers were removed. A Cheyenne man named White Elk, who was interviewed years later, said that ten warriors were chosen as decoys. These included two Arapaho, two Cheyenne, and two from each of the three Lakota groups: Oglala, Brulé, and Miniconjou. About three times more Lakota warriors fought than Cheyenne and Arapaho. White Elk said more Native Americans were present than at the Battle of the Little Bighorn later on. This would mean more than 1,000 warriors. Red Cloud was present, but his exact role in the fighting is not known. Native American armies rarely had one single leader. Hump, a Miniconjou, was a main leader in the fighting.

After leaving Fort Kearny, Fetterman's infantry fired at the small group of Native Americans. These warriors bothered his sides and taunted his soldiers. Instead of turning west towards the wagon train, Fetterman went north up Lodge Trail Ridge. Perhaps he planned to circle east, or perhaps he was drawn by the decoys. At the top of the ridge, Fetterman ignored Carrington's orders. He chose to follow the decoys north instead of turning west to help the wagon train. He moved along a narrow ridge leading to a flat area near Peno Creek. His cavalry, led by Grummond, went first, walking so the infantry could keep up. The decoys led them further, and the cavalry left the infantry behind.

About half a mile after Fetterman crossed the top of Lodge Trail Ridge, the decoys gave a signal. The Native Americans hiding on both sides of the trail charged. Fetterman's infantry took a stand among some large rocks. In close fighting, he and 49 of his men died. Their bodies were found in a small circle, huddled together for defense. A few cavalrymen were with Fetterman. But Grummond and most of the cavalry were about a mile ahead, near Peno Creek. They might have been chasing other decoys. When attacked, the cavalry retreated uphill and south, toward Fetterman and Fort Kearny. Civilians Wheatley and Fisher and several cavalrymen stopped and took cover among rocks, where they were killed. Grummond and the cavalry seemed to stay in order, leading their horses and firing. The hill was steep and covered with ice and snow, making it hard for the mostly foot-based Native Americans to get close. But they soon succeeded. Grummond was likely killed here. The cavalry kept retreating, stopping to fight in a flat area on the ridge. The Native Americans shot at the soldiers, then charged, killing them all. It took about twenty minutes to kill the infantry and another twenty minutes to kill the cavalry.

The Native Americans had few guns. They fought mostly with bows and arrows, spears, and war clubs. Only six of the 81 soldiers died from gunshot wounds.

Estimates of Native American casualties vary. Some historians say ten Lakota, two Cheyenne, and one Arapaho were killed. Some were even killed by arrows from their own side. George Bent, a Cheyenne-Anglo man, said fourteen Native American warriors died. White Elk said only two Cheyenne were killed, but he saw 50 or 60 Lakota dead. Red Cloud later remembered the names of eleven Oglala who were killed. Some estimates go up to 160 Native American dead.

Historians do not believe the higher estimates are accurate. Plains Native Americans rarely charged directly at an enemy who could defend themselves. Instead, they attacked from the sides, using their horses to find weak spots. They would retreat if the enemy fought back strongly. They would only close in for the kill when they could do so with little risk to themselves.

Aftermath and Impact

Counting Fetterman and his men, Colonel Carrington had lost 96 soldiers and 58 civilians in less than six months at Fort Kearny. Over 300 soldiers were still at the fort.

After the Fetterman Fight, Carrington prepared for an attack on the fort that evening. He ordered all his men to stand guard. All extra ammunition and explosives were put in a special room surrounded by wagons. If Native Americans attacked, the ten women and children at the fort were told to go into this room. Soldiers were told that, as a last resort, they should retreat to the room. Carrington would then blow up the room to make sure no Americans were captured alive.

That evening, a civilian named John "Portugee" Phillips volunteered to carry a message to Fort Laramie. Carrington's message told General Cooke about the disaster. He asked for immediate help and new Spencer carbine guns. Carrington sent Phillips and another messenger, Philip Bailey, that evening on the best horses. Phillips rode 236 miles to Fort Laramie in four days. A blizzard started on December 22, and Phillips rode through deep snow and freezing temperatures. He saw no Native Americans. He arrived at Fort Laramie late on December 25 during a Christmas party. He was exhausted when he delivered his message.

Carrington and 80 men carefully marched out of Fort Kearny on December 22 as the blizzard approached. They gathered the remaining bodies of those killed. On December 26, the soldiers buried Fetterman and his men in a shared trench. By January 1, Carrington's fears of an attack on the fort had lessened. The snow was deep, and Jim Bridger told him the Native Americans would stay in their camps for the winter.

General Cooke received Carrington's message. He immediately ordered that Carrington be replaced by Brigadier General Henry W. Wessells. Wessells arrived safely at Fort Kearny on January 16 with two cavalry companies and four infantry companies. One man in his group froze to death during the journey. Carrington left Fort Kearny on January 23 with his wife and the other women and children. This included the pregnant wife of the dead Lieutenant Grummond. They faced temperatures as low as -38 °F (-39 °C) during the trip to Fort Laramie. Half of the sixty soldiers escorting them suffered frostbite.

Newspaper stories unfairly blamed Carrington for the Fetterman disaster. An investigation cleared him of blame, but the report was not made public. The investigation noted that twelve companies of soldiers were at Fort Laramie in a peaceful area. But at Fort Kearny, Carrington had only five companies in a war zone. Carrington spent the rest of his life trying to fix his reputation as a soldier.

The Fetterman Fight made the nation feel uneasy. It also made the government less willing to defend the Bozeman Trail. In 1868, Fort Phil Kearny was abandoned. In November of that year, Red Cloud signed a peace agreement with the U.S. "For the first time in its history, the United States government had negotiated a peace which conceded everything demanded by the enemy and which extracted nothing in return." However, Native American control over the Powder River country lasted only eight years.

Who Fought in the Battle

Native Americans, about 2,000 warriors

| Native Americans | Tribe | Leaders |

|---|---|---|

| Lakota Sioux

|

|

|

| Northern Cheyenne

|

|

|

| Arapaho

|

United States Army Wood-cutting detachment rescue party from Fort Phil Kearny, Dakota Territory, December 21, 1866, Brevet Lieutenant Colonel Captain William J. Fetterman†, commanding

| Expedition | Regiment | Companies and others |

|---|---|---|

|

|

2nd Cavalry Regiment

|

|

| 18th Infantry Regiment

|

|

Unassigned 18th Infantry

|

| Civilians

|

|