Bozeman Trail facts for kids

Quick facts for kids The Bozeman Trail |

|

|---|---|

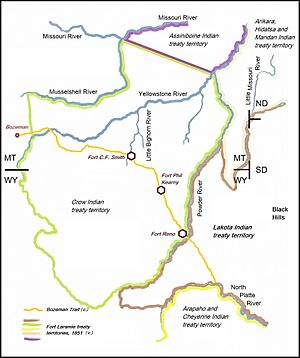

The Bozeman Trail (in yellow). Most of the trail crossed land the Crow Nation was promised in a treaty.

|

|

| Location | Montana, Wyoming |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

The Bozeman Trail was an important overland route in the western United States. It connected the gold mining areas of southern Montana to the Oregon Trail in eastern Wyoming. This trail was most used between 1863 and 1868. Even though Allen Hurlbut first explored much of the route in Wyoming, it was named after John Bozeman. Many parts of the Bozeman Trail in Montana followed paths already used by the Bridger Trail, which Jim Bridger opened in 1864.

Many pioneers and settlers traveled through lands belonging to Native American tribes. This caused anger and led to conflicts. The main groups who challenged the trail were the Lakota, Arapaho, and Cheyenne peoples. The United States believed it had the right to build "roads, military and other posts" as stated in the 1851 Fort Laramie Treaty. All groups involved had signed this treaty. However, the Crow Nation had treaty rights to this land and had lived there for many years. They supported the white settlers. The U.S. Army tried to control the trail by fighting against the opposing Native American groups. Because of its history with frontier life and conflicts, parts of the trail are now listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Contents

Why Was the Bozeman Trail Established?

In 1863, John Bozeman and John Jacobs looked for a direct path from Virginia City, Montana to central Wyoming. They wanted to connect with the Oregon Trail, which was the main route to the West Coast. Before this, most people reached southwestern Montana by traveling on the Missouri River to Fort Benton. From there, they used the 'Benton Road' around the Great Falls.

The Bozeman Trail followed many old north-south paths that Native Americans had used for a very long time. This new route was more direct and had better water sources than older trails into Montana. Bozeman and Jacobs made the trail wide enough for wagons. But there was a big problem: the trail went right through lands used by the Shoshone, Arapaho, and Lakota nations.

Long before the Bozeman Trail was created, the plains of Wyoming were busy with Crow people, white trappers, and traders. According to the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851, most of the Bozeman Trail crossed land that belonged to the Crow Nation. For the Crow, the Bozeman Trail brought new relationships with settlers and soldiers that would change their tribe greatly.

To make things more complicated, the Arapaho, Cheyenne, and Lakota had taken over the southeastern part of the Crow's land. They had moved into the western Powder River area in the 1850s. After big battles, they won this buffalo-rich land from the Crow around 1860. The main conflicts over the Bozeman Trail happened along about 250 miles of wagon tracks in this area. Travelers usually felt safer once they reached the last 190 miles of the trail, from the Bighorn River crossing to the city of Bozeman.

Who Traveled the Bozeman Trail?

During the few years the trail was open, about 3,500 people traveled on it. Between 40 and 50 of them lost their lives due to conflicts with Native Americans. At the time, this shortcut was often called "the road to Montana." The actual road was much longer than a straight line because of the hills and uneven ground. Parts of the route were changed each year to avoid the worst sections. The journey usually took about eight weeks.

Many travelers prepared for the difficult trip by reading John Lyle Campbell's popular guidebook. Some people drowned or had fatal accidents with firearms. Others became very sick with diseases like "mountain fever" and never reached their destination. Travelers sometimes hunted animals like elk, mountain sheep, bear, and buffalo. One traveler, Richard Owen, wrote in 1864, "The men are killing them in large numbers. I feel sorry to see such destruction. They leave tons of good meat every day to be devoured by wolfs at night."

Travelers often formed organized groups called "trains." These trains had chosen leaders like a captain or marshal. One group, the Townsend Wagon Train, had about 150 wagons, 375 men, 36 women, 36 children, and 636 oxen. About one-fifth of the people crossing the plains on the Bozeman Trail were women or children. Each wagon paid the train pilot, sometimes six dollars in 1864. At first, the trail was used by individuals and small families. Later, it became a supply route with large freight wagons carrying equipment and goods to the new towns in the West.

Conflicts Along the Trail

John Bozeman led the first wagon train on the trail in 1864. Abasalom Austin Townsend was the captain of another very large wagon train. His group had a battle with Native Americans on July 7, 1864, known as the Townsend Wagon Train Fight. Both sides had casualties. Attacks by Native Americans on settlers increased a lot from 1864 to 1866. This led the U.S. government to send the Army to fight against the Shoshone. Patrick Edward Connor led some of these early campaigns, including the Bear River Massacre and the Powder River Expedition of 1865. He also fought the Arapaho at the Battle of the Tongue River.

The Bozeman Trail turned north from the Oregon Trail and the California Trail into the Powder River area. In 1866, William Tecumseh Sherman approved building three forts to protect travelers on the trail. Soldiers faced harassment from Sioux Native Americans, who were led by Red Cloud. The United States later named this conflict Red Cloud's War. Colonel Henry B. Carrington was stationed at a fort halfway between Fort Laramie and the Bozeman Trail. His strong fort was not directly attacked.

However, Captain William J. Fetterman led soldiers out from Fort Phil Kearny against orders. All eighty of Fetterman's men were killed in what became known as the Fetterman Fight. After this event, the United States agreed, as part of the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868, to abandon its forts along the Bozeman Trail.

After the Civil War

In 1866, after the American Civil War ended, more settlers used the trail to reach the gold fields in Montana. That year, about 1,200 wagons brought around 2,000 people to the city of Bozeman. The Army held a meeting at Fort Laramie, which Lakota leader Red Cloud attended. The Army wanted to negotiate with the Lakota for settlers to use the trail. As talks continued, Red Cloud became very angry when he found out that U.S. soldiers were already using the route without permission from the Lakota nation. This is how Red Cloud's War began.

It was very difficult for the army to negotiate with Red Cloud and other Lakota leaders about traffic through the western Powder River area. In 1851, the United States had recognized that this land belonged to the Crow, and the Lakota tribe had also agreed to this.

That same year, Nelson Story, a successful gold miner from Virginia City, Montana, used the Bozeman Trail to successfully drive about 1,000 longhorn cattle into Montana. The U.S. Army tried to stop Story to protect his cattle from Native American attacks, but Story managed to bring his cattle through to the Gallatin Valley. This helped start Montana's cattle industry.

The Army built Fort Reno, Fort Phil Kearny, and Fort C. F. Smith along the route. These forts had troops to protect travelers. All three forts were built west of the Powder River, outside the Lakota territory recognized by the whites in the Fort Laramie Treaty. Despite this, the Sioux attacked the United States, claiming the Yellowstone area as their land. Native American attacks along the trail and around the forts continued. When the Lakota defeated a group of soldiers led by William J. Fetterman near Fort Phil Kearny on December 21, 1866, civilian travel on the trail stopped. On August 1 and August 2, 1867, U.S. forces fought off large groups of Lakota and Cheyenne trying to take over Fort C. F. Smith and Fort Phil Kearny in the Hayfield Fight and Wagon Box Fight.

The attacks on the soldiers seemed like a big Sioux war to protect their land. And it was, but the Sioux had only recently taken this land from other tribes. Now they were defending it from both other tribes and white settlers. In 1866, Red Cloud and his alliance of Lakotas, Cheyennes, and Arapahos fought for land they had controlled for only a few years.

The troops at Fort Phil Kearny and Fort C. F. Smith sometimes received warnings of attacks from the Crow. The Crow also shared information about where the Lakota camps were. The Crow were not happy that their treaty-guaranteed land was being taken over by their old enemies, the Arapahoes, Cheyennes, and Lakotas. Even though they disliked the traffic on the Bozeman Trail, the Crow still helped the soldiers in the forts.

Later, in the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie, the U.S. recognized the Powder River Country as hunting land for the Lakota and their allied tribes. Most of this land was originally Crow treaty territory, but it had been taken over by the Lakota. For a while, the government used the treaty to stop European-American settlers from traveling on the Bozeman Trail. President Ulysses S. Grant ordered the forts along the trail to be abandoned.

Red Cloud's War is often seen as the only Native American war where Native Americans achieved their goals, even if only for a short time, with a treaty settlement mostly on their terms. However, by 1876, after the Black Hills War, the U.S. Army reopened the trail. The Army continued to use the trail during later military campaigns and built a telegraph line along it.

The Bozeman Trail Today

Today, a modern highway route generally follows the same path as the historic Bozeman Trail. This route includes Interstate 25 from Douglas, Wyoming to Buffalo, Wyoming. Then it follows Interstate 90 from Buffalo through Sheridan, Wyoming to Bozeman, Montana. Finally, it uses Montana Highway 84 and U.S. Route 287 to Virginia City, Montana.

See also

In Spanish: Ruta Bozeman para niños

In Spanish: Ruta Bozeman para niños

| Georgia Louise Harris Brown |

| Julian Abele |

| Norma Merrick Sklarek |

| William Sidney Pittman |