Walking Purchase facts for kids

The Walking Purchase was a land agreement from 1737. It was made between the Penn family, who owned the land in colonial Pennsylvania, and the Lenape Native American tribe (also known as the Delaware Indians). In this agreement, the Penn family said that an older treaty from 1686 meant they owned a huge area of land. This land was about 1,200,000 acres (4,860 square kilometers) along the Delaware River. The Penn family then forced the Lenape to leave this land. The Lenape asked the Iroquois tribe for help, but the Iroquois refused.

Much later, in 2004, the Delaware Nation (a group of Lenape descendants) went to court. They claimed that 314 acres (1.3 square kilometers) of land from the original "purchase" should be returned. However, the U.S. District Court decided not to hear the case. The court said it was "nonjusticiable," meaning it was not something the court could rule on. This was true even if the Delaware Nation's claims of a dishonest deal were correct. This decision was upheld through several appeals, and the Supreme Court of the United States also refused to hear the case.

Contents

History of the Land Deal

How the Purchase Began

William Penn (1644–1718) started the Pennsylvania Colony. He was known for being fair with the Lenape people. But his sons, John Penn and Thomas Penn, did not follow their father's fair ways. In 1736, they claimed there was a deed from 1686. This deed supposedly said the Lenape would sell land starting near the Delaware River and Lehigh River. The land would stretch as far west as a man could walk in a day and a half. This became known as the "Walking Purchase" or Walking Treaty of 1737.

Some people believe this old document might have been a draft that was never signed. Others think it might have been completely made up. Even the Encyclopædia Britannica calls it a "land swindle," meaning a dishonest trick to get land. The Penns' agents started selling land in this disputed area to settlers. This happened even while the Lenape still lived there.

The "Walk" and Its Outcome

To calm the Lenape's worries, James Logan, a Penn family agent, showed them a map. The map wrongly showed the Lehigh River as the closer Tohickon Creek. It also had a dotted line showing a path that seemed fair for the "walkers." The Lenape believed the land they would lose was not too much, so they finally signed the agreement.

According to stories, the Lenape leaders thought that about 40 miles (60 kilometers) was the longest distance someone could walk in a day and a half. But James Logan hired three of the fastest runners in the colony: Edward Marshall, Solomon Jennings, and James Yeates. They ran on a path that had been prepared for them. The Sheriff of Bucks County, Timothy Smith, watched them during the "walk."

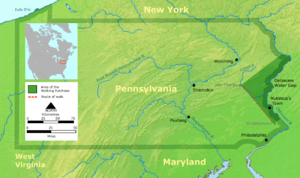

The walk happened on September 19, 1737. Only Edward Marshall finished. He reached an area about 70 miles (113 kilometers) away, near what is now Jim Thorpe, Pennsylvania. At the end of the walk, Sheriff Smith drew a straight line back toward the northeast. The Penn family then claimed all the land east of these two lines, reaching to the Delaware River.

This unfair walk resulted in the Penn family claiming a huge area of 1,200,932 acres (4,860 square kilometers). This is about the size of the state of Rhode Island. This land is now part of seven eastern Pennsylvania counties.

Lenape Forced to Move

The Lenape leaders asked the Iroquois confederacy tribe for help. The Iroquois had some authority over the Lenape. However, the Iroquois leaders decided it was not good for them to help the Lenape. James Logan had already made a deal with the Iroquois to support the colonial side. Because of this, the Lenape had to leave their lands from the Walking Purchase.

Lenape leaders like Chief Lappawinsoe protested this arrangement. The Lenape were forced to move into areas like the Shamokin and Wyoming River valleys. These places were already crowded with other Native American tribes who had also been displaced. Some Lenape later moved even further west into the Ohio Country.

Because of the Walking Purchase, the Lenape lost their trust in the Pennsylvania government. The good relationship that William Penn had started with the tribes was broken forever.

The Court Case: Delaware Nation v. Pennsylvania

District Court Decision (2004)

In 2004, the Delaware Nation sued Pennsylvania in a U.S. District Court. They wanted 314 acres (1.3 square kilometers) of land back. This land was part of the 1737 Walking Purchase and was known as Tatamy's Place. The court decided to dismiss the case.

The court noted that William Penn's government was different from other colonies. Penn tried to have a good relationship with Native Americans based on respect. But the court also mentioned the Delaware Nation's claims:

- Penn's sons were not as interested in being friends with the Lenape.

- Thomas Penn supposedly used an old, incomplete, unsigned paper as a legal contract.

- He told the Lenape chiefs that their ancestors had agreed to sell land as much as a man could walk in a day and a half.

- The Lenape chiefs trusted that the "white men" would take a slow walk. They did not know they would lose so much land.

- Thomas Penn had a straight path cleared through the forests. He hired three of the fastest runners. He even promised the fastest runner money and land.

- The runners ended up claiming 1,200 square miles (more than 1 million acres) of Lenape land. This included Tatamy's Place.

- The Lenape complained to the King of England, but it did not help.

- Later, experts said the old deed might have been a forgery.

The Delaware Nation said that Thomas Penn had "sovereign authority," meaning he had the power to rule. But they argued that the land deal was dishonest. The court decided that it could not rule on whether the original land rights were taken away fairly, even if there was a dishonest deal. This was because the land was taken before a law called the Indian Nonintercourse Act was passed in 1790.

Appeals Court Decision (2006)

The United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit agreed with the District Court's decision. This court also said that original land rights could be taken away even if there was a dishonest deal. The court also said that any land given to the tribe after their original rights were taken away could not bring those original rights back.

The Delaware Nation had argued that the King of England, not Thomas Penn, was the true ruler of the land. They said Thomas Penn could not take away their original land rights. Therefore, the Delaware Nation should still have the right to use the land. But the appeals court found that the complaint did not clearly show that Penn was only "accountable directly to the King of England."

The U.S. Supreme Court chose not to hear the case. This meant the decisions of the lower courts stood.

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |