Clarence Hudson White facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Clarence H. White

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Clarence Hudson White

April 8, 1871 West Carlisle, Ohio, U.S.

|

| Died | July 7, 1925 (aged 54) Mexico City, Mexico

|

| Known for | Photography |

| Spouse(s) | Jane Felix |

Clarence Hudson White (born April 8, 1871 – died July 8, 1925) was an American photographer and teacher. He was also a founder of the Photo-Secession movement, which helped make photography a respected art form.

Clarence grew up in small towns in Ohio. His family and the simple life of rural America greatly influenced him. After visiting a big fair called the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893, he became interested in photography. Even though he taught himself everything about photography, he quickly became famous around the world. His photos, known as pictorialism, showed the feelings and spirit of America in the early 1900s.

As his photos became well-known, other photographers wanted to learn from him. He became friends with Alfred Stieglitz, another famous photographer, and together they worked to show that photography was a true art. In 1906, White and his family moved to New York City. This helped him be closer to Stieglitz and promote his own work more.

In New York, he became very interested in teaching photography. In 1914, he started the Clarence H. White School of Photography. This was the first school in America to teach photography as an art. Because he spent so much time teaching, he took fewer of his own photos in the last ten years of his life. In 1925, he had a heart attack and died while teaching students in Mexico City.

Contents

Clarence White's Life Story

Early Years (1871–1893)

Clarence White was born in 1871 in West Carlisle, Ohio. He was the youngest of two sons. His childhood was happy and healthy. He and his older brother, Pressley, often played in the fields and hills near their small town.

When Clarence was sixteen, his family moved to Newark, Ohio. His father became a traveling salesman, so Clarence had more time to follow his own interests. He became very serious about playing the violin. In his diaries from his late teens to mid-twenties, he wrote a lot about music and art. He didn't mention photography at all during this time.

After high school, White worked as a bookkeeper at his father's company. He worked hard, but his job didn't give him much time for art. He worked six days a week, from 7 AM to 6 PM. His uncle, Ira Billman, who was a poet, encouraged him to keep developing his creative skills. By 1890, White was filling sketchbooks with drawings and watercolors.

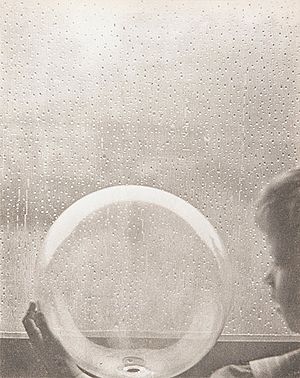

Some of the artistic ideas White developed then, he later used in his photography. He learned how to use light (or darkness) to make his subject stand out. He also learned to imagine his pictures in his mind first. For example, he once drew a woman blowing bubbles, surrounded by floating spheres. This image later appeared many times in his photographs.

White met his future wife, Jane Felix (1869–1943), through his love for music around 1891–92. She was a schoolteacher. His diaries show he took her to concerts. They married on June 14, 1893, at 6 AM. Right after their wedding, they took a train to Chicago to visit the World's Columbian Exposition. This huge fair had over 26 million visitors. It was filled with art, music, and new technology. It was there that White first saw photography as a public art form. There were many photo exhibits, camera makers, and portrait studios. It was like a crash course in the world of photography for him.

Becoming a Photographer (1893–1899)

We don't know exactly when White started photography after returning to Newark, but it was very soon. He took at least two photos in 1893, and by the next year, he was deeply involved. His grandson wrote that White's wife, Jane, was a huge support. She was a wife, mother, and business manager. She modeled for him and helped him focus on his art. White often used "we" or "Mrs. White and I" when talking about his photography, showing her big influence.

When they returned to Newark, White and his wife weren't rich. They lived with his parents, and he kept his bookkeeping job. He didn't plan to make photography his career at first. Even after he became successful, he worked as a bookkeeper for many years. Most of his money went to his family, so his early photography was hard financially. A student later remembered White saying he could only afford two glass plate negatives a week. He would spend all his free time planning what to do with those two plates on the weekend.

White taught himself everything about photography. He couldn't afford formal training. Many friends and students believed this was his greatest strength. When he had his first solo exhibition in Newark in 1899, a fellow photographer, Ema Spencer, wrote that White was "remote from artistic influences." She said he ignored traditional rules and followed his own unique ideas because he had "genius." At that time, there were no formal photography schools in the U.S. Most new photographers learned by working with experienced ones, but there weren't many in Newark.

In 1895, their first son, Lewis Felix White, was born, followed by Maynard Pressley White a year later. By the time Maynard was born, the Whites had moved into their own house. White's photography was good enough that he showed his first photos publicly at the Camera Club of Fostoria, Ohio.

A year later, he won a Gold Medal at the Ohio Photographers Association exhibition. Two photos that likely won awards were Study (Leticia Felix) and The Readers. He also won the Grand Prize for these at the First International Salon in Pittsburgh. A sculptor named Lorado Taft saw White's work and said, "White knew nothing about the technic [sic] of photography, but the artists went wild over his pictures. I saw, and went wild too!"

In 1898, White's fame grew even more. His photos appeared in national magazines for the first time. He traveled to the East Coast to talk about photography as art with other photographers. In Philadelphia, he met F. Holland Day and Joseph Keiley. In New York, he met Alfred Stieglitz, who would become a close friend for many years.

It's amazing that during this time, White's limited money meant he could only create about eight photos each month. Yet, the quality of these images was so high that he quickly became famous. He also worked under tough conditions. Because of his long hours at his bookkeeping job, he asked family and friends to pose for him in the evenings or very early mornings. Sometimes they had to wake up at 4 AM in the summer to pose before he went to work.

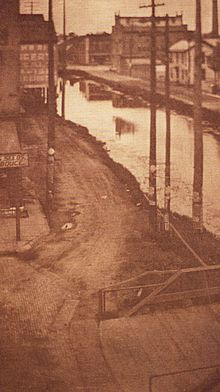

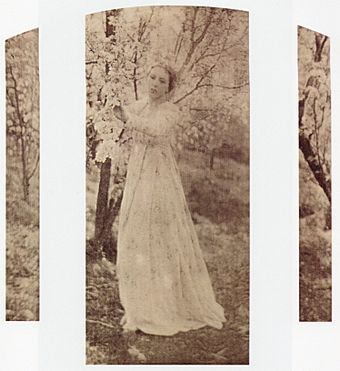

In 1898 alone, White created several of his most famous photos, including The Bubble, Telegraph Poles, Girl with Harp, Blind Man's Bluff, and Spring ‒ A Triptych.

The Newark Camera Club

To learn more about photography and encourage others in his small town, White started the Newark Camera Club in 1898. It had 10 local members who were all amateur photographers interested in pictorialism (making photos look like paintings). White's leadership quickly made the club famous far beyond Ohio. Ema Spencer, a club member, said it was known as "the White School," showing how important White was. The club wanted to have at least one big show of its members' work each year. They also wanted to show photos from other places so their own work could improve.

Thanks to White's connections, the very next year the club held a large exhibit. It included photos by Alfred Stieglitz, F. Holland Day, Frances Benjamin Johnston, Gertrude Käsebier, and Eva Watson-Schütze. The next year, they showed photos by these artists again, plus Robert Demachy, Zaida Ben-Yusuf, Frank Eugene, and the then-unknown Edward Steichen. Even though Newark was a small, isolated town, the Newark Camera Club, led by White, quickly made it "a force in the world of photography." By 1900, most major pictorial photographers in the U.S. had visited or planned to visit White. One critic said he "brought the world to Newark."

Growing as an Artist (1899–1906)

By 1899, White was so famous that he had solo shows in New York and Boston. He also showed his work in London. When the Newark Camera Club held a big exhibit of pictorial photography, White showed 135 of his own works. This show later went to the Cincinnati Art Museum. Also, one of White's simple family scenes, a portrait of his son Maynard, was printed in Stieglitz's new magazine, Camera Notes.

In the same year, White's father died at 52. This didn't stop White's art. He kept exhibiting and traveled to take portraits of friends and clients. On one trip, he met the socialist leader Eugene Debs. White became good friends with Debs and other socialist leaders like Clarence Darrow. They wrote letters and had long talks. White's belief in socialist values was one of the few things he was passionate about besides photography. After visiting a friend, White wrote, "I've never spent a week so full of inspiration since I've used a camera." His family, who were "brass-bound Republicans," hoped this interest was temporary, but White kept these beliefs his whole life.

In 1900, White joined The Linked Ring, a famous photography group. He was also a judge and exhibitor at major photo salons in Chicago and Philadelphia. He introduced his discovery, Edward Steichen, to Stieglitz. Steichen stopped in New York on his way to Paris, and he and Stieglitz became lifelong friends. Around this time, F. Holland Day organized a big exhibition in London called "The New School of American Photography." More than two dozen of White's photos were in the show, which also went to Paris and Germany. Day wrote that White was "the only man of real genius known to me who has chosen the camera as his medium of expression."

Around this time, White wrote to Stieglitz, "I have made up my mind that art in photography will be my life work." He said he was ready to live a simple life to do this. His words were true, as he struggled financially his whole life. He was known as a great photographer but not a good businessman.

A little over a year later, Stieglitz started the Photo-Secession. This was the first group in America to promote pictorialism and fine art photography. He invited White and 10 others to be "charter members." Stieglitz controlled the group strictly. He quickly planned an exhibition of their photos, including several by White, at the National Arts Club. Soon after, Stieglitz created a new magazine called Camera Work to show the Photo-Secessionists' work. White had five photos in the July 1903 issue and five more in January 1905. Being in Camera Work and a Photo-Secession member meant White was part of Stieglitz's inner circle. Stieglitz was considered one of the top promoters of art photography in the world.

Using photos to illustrate books was a new idea then. Starting in 1901, White worked on three projects to illustrate books. He first provided photos for Irving Bacheller's book Eben Holden, which became a national best seller. In 1904, White illustrated his uncle Ira Billman's poetry book, Songs for All Seasons, and a magazine article for McClure's.

Until then, White had done all his photography while still working his day job in Newark. With all his recent fame, he finally decided he might be able to make a living as a photographer. He quit his job and became a professional photographer. He wrote to his friend F. Holland Day, "It came about this way ‒ quit at 5 p.m. and at 7:30 p.m. I was ready to start to Chicago where I'd been called by Mr. Darrow in regards [to] illustrating a book of his…"

Soon after, White won a Gold Medal at the First International Salon of Art Photography in The Hague. Several of his photos were also shown in the first exhibition by Photo-Secession members at Stieglitz's new Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession.

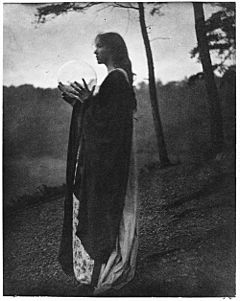

White's life was often busy, but he and his wife took a short break each summer in Maine. F. Holland Day invited them to stay at his cabin. They had done this every year since 1905. This break from summer heat and business worries allowed White to focus only on his work. Both "The Pipes of Pan" (1905) and "The Watcher" (1906) were made during his time in Maine.

New York and Professionalism (1906–1913)

In early 1906, White decided to leave Newark and move to New York City. He and his wife had become close friends with East Coast photographers like Stieglitz, Day, Käsebier, Steichen, and Eugene. These artistic connections became more important than their friends in Newark. Stieglitz and his Photo-Secession group were at the center of these connections.

As they prepared to move, Mrs. White found out she was pregnant. Since the early months were difficult, she stayed in Newark until after the baby was born. In September, White moved to New York with his two sons and his widowed mother, who cared for the boys. Their third son, Clarence Hudson White, Jr., was born in January 1907. Mrs. White stayed in Newark until June of that year.

The year 1907 was very important for White. Arthur Wesley Dow, a painter, photographer, and teacher, led the art department at Columbia University. Dow, who had known White for at least five years, asked White to be a part-time lecturer in art photography at Teachers College, part of Columbia. This showed how much White's art was recognized internationally, especially since he only had a high school education and no formal art training. He quickly loved his new job. It gave him a steady income and freed him from managing a business (White was not good at billing clients).

In the same year, White and Stieglitz worked together on an art experiment. They took a series of photos of two models. Stieglitz suggested poses, White focused the camera, and one of them would take the picture. White also developed the negatives and printed the photos. They tried different printing techniques and papers. On some prints, they signed with a monogram combining both their initials. During this time, White learned the Autochrome color process from Stieglitz, who had just returned from Europe with this knowledge. They even created and exhibited at least one Autochrome together.

In 1908, Stieglitz showed his admiration for White by dedicating an entire issue of Camera Work to him and 16 of his photographs. This was only the third time Stieglitz had honored a single photographer this way.

White was such a good teacher at Columbia that in 1908, he became an instructor at the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Science (now the Brooklyn Museum). He kept this job for 13 years, even while running his own school and teaching workshops.

While visiting Day in Maine in 1910, White found a small, old cabin. He convinced the owner to sell it to him very cheaply. He then bought land nearby and moved the cabin there. After rebuilding and enlarging it, White started the Seguinland School of Photography. Named after a nearby hotel, Seguinland was the first independent photography school in America. White asked his friend Max Weber to teach with him. His colleagues Day and later Käsebier would review student work at the end of each summer. Students came from all over, attracted by White's reputation and low tuition. One-, two-, and four-week sessions cost $20, $30, and $50. White and his wife created a friendly, family-like atmosphere. They took classes on picnics and outings by the seashore. Seguinland lasted until 1915. White's new school in New York became too much to manage financially.

Also in 1910, Stieglitz organized a major exhibition of Photo-Secession artists at the Albright Gallery in Buffalo, New York. Stieglitz, known for being bossy, refused to let anyone else have a say in who was included or how the show was displayed. This was too much for several people who had been close to him. First Käsebier, then White, and finally Steichen ended their friendships with Stieglitz. They all said Stieglitz was too controlling and made decisions for the Photo-Secession without asking its "members."

Stieglitz reacted angrily to these claims, especially White's departure. Soon after, he sent White most of the negatives and prints they had made together in 1907. The split was so deep that Stieglitz wrote to White, "One thing I do demand…is that my name not be mentioned by you in connection with either the prints or the negatives…Unfortunately I cannot wipe out the past…."

Teacher and Leader (1914–1920)

The Clarence H. White School of Modern Photography

Encouraged by the success of the Seguinland School and his new freedom from Stieglitz, White started the Clarence H. White School of Photography in 1914. He asked Max Weber and Paul Lewis Anderson to join him. White taught photographic style and meaning. Weber taught design and art theory. Anderson taught about cameras and equipment. Jane White managed the school, handled money, and helped her husband with daily tasks.

Over the next ten years, the School attracted many students who became famous photographers. These included Ruth Matilda Anderson, Margaret Bourke-White, Anton Bruehl, Dorothea Lange, Paul Outerbridge, Laura Gilpin, Ralph Steiner, Karl Struss, Margaret Watkins, and Doris Ulmann.

One reason for the school's success was White's teaching style. He focused on each student's personal vision and style, rather than a specific art movement. Students were given "problems" and asked to create images that showed certain ideas or feelings, like "Innocence" or "Thanksgiving." He also made students experiment by making different types of prints of the same image. Of the 30 hours of instruction each week, 14 were for "The Art of Photography," taught by White. In these classes, White stressed that students needed to learn "the capacity to see." He never compared students' work or encouraged competition. Each person's work was judged on its own.

This idea applied no matter what the student's final goal was. White understood that not everyone was an artist. The School taught photography as both a fine art with techniques and a practical art useful in business and industry. Some students went on to work in journalism, advertising, industry, medicine, and science.

White was best known for his weekly comments on student work. These were described as "sympathetic yet searching criticisms." They showed students their weaknesses but always made them feel brave and strong. His student Marie Riggin Higbee Avery said that the training and spirit fostered by White helped even the "least promising" students achieve "high honor in the photograph world."

Besides classes, White also created extracurricular activities. Later, a Friday evening guest speaker series included Stieglitz, Steichen, Paul Strand, and Francis Bruguière. Former students like Paul Outerbridge, Doris Ulmann, and Anton Bruehl also spoke.

One special thing about White as a teacher was how much he encouraged women photographers. White sought out and personally coached many aspiring female photographers. They liked his open mind to different styles and techniques, especially when most men had very strict views. Ralph Steiner remembered that White "always found something to praise," which made many women admire him. By 1915, there were about twice as many women as men at the school. This continued until the 1930s.

White's encouragement of women was very different from Stieglitz, who often ignored many talented women photographers of his time. After White's death, Stieglitz wrote that White's female students were "half-baked dilettantes ‒ not a single real talent…."

After several years, former students made up most of the White School instructors. In 1918, Charles J. Martin, a former student, took over when Weber left. Margaret Watkins, an early student, became known for her tough critiques of technical aspects when she taught from 1919 to 1925. Other students who became teachers included Margaret Bourke-White, Bernard Horne, Arthur Chapman, Anton Bruehl, Robert Waida, and Alfred Cohn.

From 1921–25, the School offered summer sessions in both New York and Canaan, Connecticut. Summer sessions briefly returned from 1931–33 in Woodstock, New York, but after that, all classes were in New York.

Pictorial Photographers of America

In early 1916, White, along with Gertrude Käsebier, Karl Struss, and Edward Dickinson, founded the Pictorial Photographers of America (PPA). This was a national group dedicated to promoting pictorial photography. Like the Photo-Secession, the PPA held exhibitions and published a journal. But unlike the Photo-Secession, the PPA was open to everyone and wanted to use pictorial photography for art education. In the 1920s, the PPA started to include other photography styles, bringing more variety to pictorialism.

Just like with his School, White made sure the PPA welcomed women and included them in its leadership. Käsebier was the organization's first honorary vice-president. Women were on its executive committee and other important groups. According to the PPA's first report in 1917, women made up 45 percent of the members.

White was the association's first president, serving from 1917 to 1921. He stepped down because he believed a change in leadership would benefit the organization. For a few years, the PPA's annual meeting was held with the White School summer sessions in Connecticut.

In 1921, the PPA joined with other art organizations to open a building called the Arts Center. The goal was for these groups to work together and improve "the public standard of utilitarian art." White believed the future of photography was linked to the fast-growing field of magazine illustration. Soon, lectures at the Arts Center had titles like "Pictorial Principles Applied to Architectural Photography."

Later Life (1920–1925)

World War I was very hard for White because of his socialist beliefs. He hated war and struggled with how to react when so much of the country supported it. His family faced a crisis when his sons Maynard and Lewis joined the Army. Lewis was quickly discharged due to a heart problem, but Maynard stayed until the war ended. Also, his colleague Karl Struss was sent to a detention camp because of his German background.

White focused more than ever on his teaching to distract himself from these problems. He rarely took photos during this time. Many of his colleagues were also affected. Perhaps because they missed how things were before the war, White and Stieglitz slowly became friends again. This was the only bright spot in a difficult period. In 1923, White wrote to Stieglitz, saying, "I understand that [George] Seeley is doing nothing; Coburn likewise; Day sick in bed. I do not know whether I can again do anything, but I hope someday to try."

To lift his spirits and find new ideas, White decided to go to Mexico in the summer of 1925. It was meant to be a teaching trip, as several students went with him, and a chance for him to start photographing again. He arrived in Mexico in early July. Showing his fame, he was immediately visited by Mexican President Plutarco Elías Calles.

Tragedy struck on July 7 when White suddenly had a heart attack after taking some of his first photos in years. He died 24 hours later, at 54 years old. His son Maynard arrived after his death and brought his body back to Newark for a funeral and burial. Only his family and friends from his hometown could attend the services.

After White's Death

Even though White and Stieglitz had tried to fix their friendship before White died, Stieglitz never fully forgave White for leaving him in 1912. When he heard about White's death, Stieglitz wrote, "Poor White. Cares and vexation. When I last saw him he told me he was not able to cope with [life as well as he was] twenty years ago. I reminded him that I warned him to stay in business in Ohio ‒ New York would be too much for him. But the Photo-Session beckoned. Vanity and ambitions. His photography went to the devil." Despite these harsh words, Stieglitz had 49 of White's photographs, including 18 they made together, in his own collection when he died.

The White School continued under Jane White's leadership until 1940. She then no longer had the energy to keep up with the long hours and many students. Her son, Clarence H. White Jr., took over and briefly increased enrollment. However, a poorly timed move to a larger building for new students happened just as World War II began. The School's enrollment quickly dropped, and it finally closed in 1942.

In 1949, White Jr. was offered the chance to start a photography department at Ohio University. He followed in his father's footsteps, creating a school that was "second to none." White Jr. died in 1978 at age 71.

In 1986, Clarence H. White was honored by being inducted into the International Photography Hall of Fame and Museum.

Photography Style and Technique

From the start, White's artistic vision was greatly shaped by the small-town life in Ohio. He "celebrated elemental things," like playing in fields or woods, the simple joy of slow living, and indoor games. White grew up in a big family and didn't know much about other societies. His pictures were like his own private story, protected from the outside world.

Because he worked long hours at his accounting job (often 7 AM to 6 PM, six days a week), White usually took photos just after sunrise or just before sunset. He once wrote, "My photographs were less sharp than others and I do not think it was because of the lens so much as the conditions under which the photographs were made ‒ never in the studio, always in the home or in the open, and when out of doors at a time of day very rarely selected for photography." He also knew his subjects very well, as they were usually his wife, her three sisters, and his own children.

However, White's photos were not just casual snapshots. He carefully controlled every detail in his scenes. Sometimes he even had special costumes made for his models. He knew exactly what he wanted in his mind and then made it happen with his camera. It's been said that White is important in photography history because he changed how pictures were made in his early years. He created a new, modern style for his time. He simplified his compositions to very basic shapes and lines. By experimenting with design ideas from artists like Whistler and Japanese prints, he created a unique personal style for photography.

Peter Bunnell wrote that White's photos are memorable because of their form and content. In his best pictures, every element, every line and shape, is placed with such strong feeling that few other photographers achieved it. White could turn the feeling of light into a clear display of photography's most basic idea: creating shapes through light itself. His prints, mostly made with platinum, show a richness, softness, and glow that is rare in photography history.

While White is mostly known for his family scenes and portraits, his work "is not genre because it really tells us very little about the individuals shown or the world they live in. White subject's are apparently just there, and that's about the end of it. What we seem to have here is a 'pure photography'."

It's interesting that even though White lived in New York City from 1906 to 1925, his photos don't show it. There are no street scenes, city people, buildings, bridges, ships, or cars. Unlike most of his photographer friends, he chose to ignore the city he lived in. He only used New York for promoting his work and teaching. Even though he was practical about earning a living and advancing his art, he stayed true to his small-town roots his whole life.

For most of his life, White had limited money for cameras and lenses. He once said, "The most important factor in the selection [of his equipment] being a $50.00 limit." For most of his time in Newark, he used a 6 1/2" x 8 1/2" view camera with a 13" Hobson portrait lens.

White used several different printing processes, including platinum, gum-platinum, palladium, and cyanotype. His platinum prints used platinum salts, which gave them a greater range and richness of middle tones compared to modern platinum prints.

White sometimes printed the same image using different processes. This means his prints can look very different. For example, his platinum prints have a deep magenta-brown color, while his gum prints have a distinct reddish tint. Photogravures of his images in Camera Work, which he considered true prints, were more neutral, with warm black-and-white tones.

Before 1902, White dated his photos based on when the negative was made, even if he printed it later. For his later prints, he often gave two dates: one for when the picture was taken and another for when it was printed.

Famous Quotes About White

- "I think that if I were asked to name the most subtle and refined master photography has produced, that I would name him... To be a true artist in photography one must also be an artist in life, and Clarence H. White was such an artist." — Alvin Langdon Coburn

- "What he brought to photography was an extraordinary sense of light. The Orchard is bathed in light. The Edge of the Woods is a tour de force of the absence of light." — Beaumont Newhall

- "Clarence White's poetic vision and sensitive intuition produced images that insinuate themselves deeply into one's consciousness." — Edward Steichen

- "Anyone who came under his influence never got over it." — Stella Simon, a White School student and famous photographer

- "To Clarence H. White, one of the very few who understand what the Photo-Secession means & is." — Inscription from Alfred Stieglitz to White

- "The man was a good teacher, a great teacher, and I can still occasionally think 'I wish he were around. I'd like to show him this.' Isn't that odd, that that stays with you?" — Dorothea Lange

Gallery

-

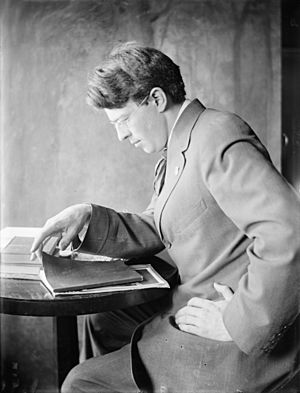

Experiment #27 – Jointly created by White and Alfred Stieglitz

See also

In Spanish: Clarence Hudson White para niños

In Spanish: Clarence Hudson White para niños