Edward Weston facts for kids

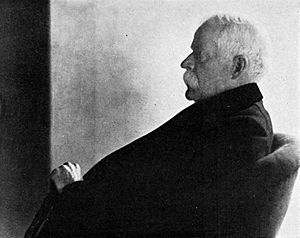

Edward Henry Weston (born March 24, 1886 – died January 1, 1958) was an important American photographer from the 20th century. Many people call him "one of the most creative and influential American photographers." He is also known as "one of the masters of 20th-century photography."

During his 40-year career, Weston photographed many different things. These included landscapes, still life pictures, portraits, and everyday scenes. He was known for his "American, especially Californian, way of modern photography." This was because he focused on the people and places of the American West. In 1937, Weston was the first photographer to receive a Guggenheim Fellowship. This special award helped him create almost 1,400 photos over the next two years. He used a large 8 × 10 view camera for these pictures. Some of his most famous photos show the trees and rocks at Point Lobos, California. He lived near there for many years.

Weston was born in Chicago and moved to California when he was 21. He knew he wanted to be a photographer from a young age. At first, his photos looked like the popular "soft focus" style of the time. But within a few years, he changed his style. He became a leader in making very clear and detailed photographic images.

In 1947, he was diagnosed with Parkinson's disease. This illness made him stop taking photos. He spent the last ten years of his life making sure over 1,000 of his best photos were printed well.

Contents

Edward Weston's Photography Journey

Early Life and First Camera (1886–1906)

Edward Weston was born in Highland Park, Illinois. He was the second child and only son. His father was a doctor, and his mother was an actress. Sadly, his mother died when he was five years old. His older sister, Mary, mostly raised him. They were very close.

When Edward was nine, his father remarried. But Edward and his sister did not get along with their new stepmother. After his sister got married and moved away, Edward felt alone. He stopped going to school and spent a lot of time by himself.

For his 16th birthday, Edward's father gave him his first camera. It was a simple Kodak Bull's-Eye No. 2. He took it on a trip. When he came back, he was so interested in photography that he bought a used 5 × 7 inch view camera. He started taking pictures in Chicago parks and on his aunt's farm. He also developed his own film and prints. He later said that even his early work showed artistic talent.

In 1904, his sister moved to California. Edward felt even more alone in Chicago. He worked at a department store to earn money. But he spent most of his free time taking photos. By 1906, he was confident enough to send his work to a magazine. In April 1906, Camera and Darkroom published his picture Spring, Chicago. This was his first known published photo.

Edward also took part in the men's double American round archery event at the 1904 Summer Olympics. His father also competed in the same event.

Becoming a Professional Photographer (1906–1923)

In 1906, Edward moved to Tropico, California, near his sister. He wanted to be a professional photographer. He soon realized he needed more training. A year later, he went to the Illinois College of Photography. He finished the course quickly.

He then worked at photography studios in Los Angeles. He learned how to retouch negatives and run a studio. This helped him understand the business of photography.

Edward met Flora May Chandler, his sister's best friend. She was a school teacher. In 1909, Edward and Flora got married. Their first son, Edward Chandler Weston, was born in 1910. He also became a good photographer and helped his father.

In 1910, Weston opened his own studio in Tropico. He called it "The Little Studio." He wanted to make his name famous, no matter where he lived. He was very careful about his work. He would use many photographic plates until he got the perfect shot.

His hard work paid off. He won awards in national contests. He also published more photos and wrote articles for magazines. He supported the "pictorial style" of photography at this time.

His second son, Theodore Brett Weston, was born in 1911. Brett later worked with his father and became an important photographer himself.

Around 1913, another Los Angeles photographer, Margrethe Mather, visited Weston's studio. She was very artistic and outgoing. Weston found her ideas interesting. He asked her to be his studio assistant. For ten years, they worked closely together. They took portraits of famous writers. Weston later said she was "the first important person in my life."

In 1915, Weston started keeping detailed journals called "Daybooks." He wrote about his work, photography ideas, and his life. His third son, Lawrence Neil Weston, was born in 1916. He also became a photographer. Weston also met photographer Johan Hagemeyer and helped him.

His fourth son, Cole Weston, was born in 1919. Flora, his wife, spent most of her time caring for their four sons.

In 1920, Weston met Roubaix de l'Abrie Richey and Tina Modotti. The next year, Mather became an equal partner in his studio. They signed their portraits with both their names. This was the only time Weston shared credit with another photographer.

In 1922, he visited his sister in Ohio. There, he took photos of tall smokestacks at a steel mill. These photos showed a big change in his style. He moved from soft-focus pictures to a new, sharper style. He knew this was important. He wrote, "That day I made great photographs."

He then traveled to New York City. There, he met famous artists and photographers like Alfred Stieglitz. Stieglitz told him, "Your work and attitude reassures me."

Soon after, Robo, a friend, moved to Mexico. He planned an art show there. Tina Modotti went to Mexico to join him, but Robo sadly died. Modotti decided to stay and put on the show. It was a success and made Weston's art famous in Mexico.

Adventures in Mexico (1923–1927)

On July 30, 1923, Weston, his son Chandler, and Tina Modotti sailed to Mexico. His wife, Flora, and their other three sons waved goodbye. They arrived in Mexico City in August. Within a month, Weston had an art show. It opened to great reviews. He was proud of a review that said, "Photography is beginning to be photography, for until now it has only been art."

The new culture and scenery in Mexico made Weston see things differently. He started photographing everyday objects like toys and doorways. His fame grew in Mexico. He had another show in 1924. Many local people asked him to take their portraits. But Weston started to miss his other sons in the U.S.

He and Chandler returned to San Francisco in late 1924. He set up a studio with Johan Hagemeyer. Weston seemed to be thinking about his past and future. He even burned his old journals from before Mexico.

In August 1925, he went back to Mexico, this time with his son Brett. Modotti had arranged a joint show of their photos. It opened the week he returned. He received more praise. Six of his prints were bought by the State Museum. He focused on photographing folk art and local scenes. One of his best photos from this time shows three black clay pots. An art historian called it "the beginning of a new art."

In May 1926, Weston signed a contract to take photos for a book about Mexican folk art. He, Modotti, and Brett traveled around the country. Brett learned a lot about photography from his father during this trip.

By the time they returned, Weston and Modotti's relationship had ended. Within two weeks, he and Brett went back to California. He never traveled to Mexico again.

From Glendale to Carmel (1927–1935)

Weston first returned to his old studio in Glendale. He quickly set up a show of photos he and Brett had taken. Brett was only 15 years old at the time.

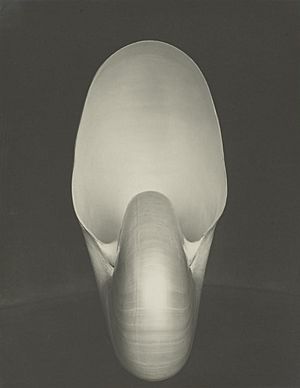

He also met Canadian painter Henrietta Shore. Weston was interested in her large paintings of seashells. He borrowed some shells from her. He wanted to find inspiration for new still life photos. He explored many different shell and background combinations. One of these, called Nautilus (1927), became one of his most famous images.

In September 1927, Weston had a big exhibition in San Francisco. There, he met fellow photographer Willard Van Dyke. Van Dyke later introduced Weston to Ansel Adams.

In May 1928, Weston and Brett took a short but important trip to the Mojave Desert. This was where Weston first photographed landscapes as art. He loved the stark rocks and empty spaces. He took 27 photos there. He wrote in his journal that these were "the most important I have ever done."

Later that year, he and Brett moved to San Francisco. They worked in a small studio. Weston wanted to be alone and focus on his art. In early 1929, he moved to a cottage in Carmel. There, he found the quiet and inspiration he needed. He put a sign in his studio window: "Edward Weston, photographer, Unretouched Portraits, Prints for Collectors."

He started taking regular trips to nearby Point Lobos. He continued to photograph there for the rest of his career. He learned to perfect his vision for his view camera. His photos of kelp, rocks, and wind-blown trees from this time are among his best.

In April 1929, Weston met photographer Sonya Noskowiak. Soon after, she moved in with him. She became his model, student, and assistant. They lived together for five years.

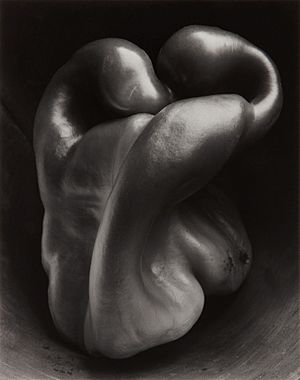

Weston was fascinated by the many shapes of kelp on the beaches near Carmel. In 1930, he began taking close-up photos of vegetables and fruits. He photographed cabbage, onions, bananas, and finally, peppers. In August, Noskowiak brought him some green peppers. Over four days, he took at least thirty different photos. Of these, Pepper No. 30 is one of the greatest photos ever made.

Weston had several important solo exhibitions in 1930–31. These shows received excellent reviews, including an article in the New York Times Magazine.

His personal life was complicated. His wife, Flora, had lost most of her savings in the Wall Street Crash of 1929. Weston felt more pressure to help support her and their sons. He called this "the most trying economic period of my life."

In 1932, The Art of Edward Weston was published. It was the first book just about his work.

Around the same time, a group of photographers in San Francisco, including Van Dyke and Ansel Adams, started meeting. They were inspired by Weston's work. They formed a group called Group f/64. In November 1932, they had a show at a museum. It was a big success.

In early 1934, Weston met Charis Wilson. He was immediately drawn to her. He wrote, "A new love came into my life." They took trips to Oceano Dunes. This freedom, along with his sons growing up, gave Weston the courage to finally divorce his wife, Flora. They had been living apart for 16 years.

Guggenheim Grant and Wildcat Hill (1935–1945)

In January 1935, Weston faced money problems. He closed his studio in Carmel and moved to Santa Monica Canyon. There, he opened a new studio with his son Brett.

Weston decided to apply for a Guggenheim Foundation grant. This is a special award for artists. He sent in a short description of his work and 35 of his favorite photos. Later, he sent a longer letter and work plan, which Charis Wilson helped him write.

On March 22, 1937, Weston learned he had won the Guggenheim grant. He was the first photographer to receive this award. It was $2,000 for one year, a lot of money back then. This allowed him to travel and photograph whatever he wanted. Over the next year, he and Charis took 17 trips and drove over 16,000 miles. Weston took 1,260 photos during this time.

Because of his success, Weston received a second year of Guggenheim support. He used most of the money to print his photos from the past year. He also had his son Neil build a small home in the Carmel Highlands. They called it "Wildcat Hill."

In 1939, Seeing California with Edward Weston was published. It had Weston's photos and writing by Charis Wilson. Feeling happy and financially secure, Weston married Charis Wilson on April 24.

In 1940, they published another book, California and the West. Weston also taught photography at the first Ansel Adams Workshop.

As the Guggenheim money ran out, Weston was asked to take photos for a new edition of Walt Whitman's book, Leaves of Grass. He would get $1,000 for photos and $500 for travel. Weston insisted on choosing the images himself. He and Charis traveled 20,000 miles through 24 states. He took hundreds of photos.

On December 7, 1941, Pearl Harbor was attacked, and the United States entered World War II. Weston was deeply affected by the war. He quickly returned home.

He spent early 1942 organizing and printing the photos from the Whitman trip. Forty-nine of his images were chosen for the book.

During the war, Point Lobos was closed. Weston continued to photograph around Wildcat Hill, including the many cats that lived there. Charis put these cat photos into a book called The Cats of Wildcat Hill, published in 1947.

In 1945, Weston started showing symptoms of Parkinson's disease. This illness slowly took away his strength and ability to photograph. He and Charis began to drift apart. She became more involved in local activities. They separated while he was working on a big art show for the Museum of Modern Art. Weston moved back to Glendale.

Later Years and Legacy (1946–1958)

In February 1946, Weston's major art show opened at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. They displayed 250 of his photographs. He sold 97 prints from the exhibit. Later that year, Kodak asked Weston to create color photos for their advertising. Weston had never worked in color before. He accepted because they offered him $250 per image, the most he ever earned for a single work. He sold seven color photos of landscapes at Point Lobos.

In 1947, as his Parkinson's disease got worse, Weston looked for an assistant. A young photographer named Dody Weston Thompson contacted him. She became his full-time assistant in 1948.

By late 1948, he could no longer use his large camera. He took his last photos at Point Lobos that year. His final photo was called Rocks and Pebbles, 1948. Even though he couldn't take pictures, Weston continued to work. He worked with his sons and Dody to organize and print his photos. In 1950, he had a major show in Paris. In 1952, he published a Fiftieth Anniversary portfolio, with photos printed by Brett.

He worked with his sons Cole and Brett, and Dody Thompson (who married Brett), to choose his best work. They spent many hours in the darkroom. By 1956, they had made "The Project Prints." These were eight sets of 8" × 10" prints from 830 of his negatives. One complete set is at the University of California, Santa Cruz. Later that year, the Smithsonian Institution showed almost 100 of these prints in an exhibit called "The World of Edward Weston."

Edward Weston died at his home on Wildcat Hill on January 1, 1958. His sons scattered his ashes into the Pacific Ocean at Point Lobos. The beach was later renamed Weston Beach because of his influence.

Photography Tools and Methods

Cameras and Lenses

Weston used several cameras during his life. He started with a 5 × 7 camera in 1902. When he opened his studio in 1911, he got a huge 11 x 14 studio portrait camera. He also bought a smaller 3 ¼ x 4 ¼ Graflex in 1912 to photograph children.

When he went to Mexico in 1924, he took an 8 × 10 Seneca folding-bed view camera with several lenses. He also bought a used lens there that he used for many years. He also had a smaller 3¼ × 4¼ Graflex for portraits.

In 1933, he bought a 4 × 5 R. B. Auto-Graflex for all his portraits. He kept using the Seneca view camera for other work.

By 1939, his main equipment included:

- 8 x 10 Century Universal camera

- Triple convertible Turner Reich lens

- Filters (K2, G, A)

- 12 film holders

- Paul Ries Tripod

He used this equipment for the rest of his life.

Film Use

Before 1921, Weston used a type of film called orthochromatic. But when panchromatic film became available in 1921, he switched to it. His son Cole said that after Agfa Isopan film came out in the 1930s, Weston used it for all his black-and-white photos. This film was not very sensitive to light.

His 8 × 10 cameras were big and heavy. Because of the weight and cost of the film, he never carried more than twelve sheets of film. At the end of each day, he had to go into a darkroom to load new film. This was tricky when he was traveling.

Even with the large camera, Weston was fast. He could set up his camera, focus, and take a picture in just over two minutes. The smaller Graflex cameras used film magazines. Weston liked these for portraits because he could take pictures more quickly. He once took 36 photos of Tina Modotti in 20 minutes with his Graflex.

In 1946, Kodak asked Weston to try their new Kodachrome color film. Over the next two years, he made at least 60 color photos with it. These were some of the last photos he took. By late 1948, he could no longer use a camera because of Parkinson's disease.

Exposure Settings

For the first 20 years, Weston guessed his exposure settings based on his experience. He said he "felt" his exposures were more accurate that way. In the late 1930s, he got a Weston exposure meter. He used it to help him, but he still trusted his own judgment.

Weston believed in "massive exposure." This meant he used long exposure times. He then carefully developed the film by hand. He would inspect each negative to get the right balance of light and dark.

Because the film he used was not very sensitive, his view camera needed very long exposures. These could be from 1 to 3 seconds for landscapes. For still life photos like peppers or shells, they could be as long as 4 and a half hours! When he used the Graflex cameras, the exposure times were much shorter, usually less than a quarter of a second.

Darkroom Work

Weston always made contact prints. This means the print was the exact same size as the negative. He preferred platinum printing early in his career. This method needed ultraviolet light. Since he didn't have an artificial light, he had to place the print in direct sunlight. This meant he could only print on sunny days.

If he wanted a print larger than the original negative, he used a special process. He would make a larger "inter-positive" first. Then he would make a new, larger negative from that. This was a lot of work.

In 1924, Weston wrote about his darkroom process. He developed each sheet of film one at a time in a tray. He watched each one under a special light to control how it developed. He used this method for the rest of his life.

Weston also used techniques like dodging and burning. These helped him control the light and dark areas in his prints.

Paper Choices

Early on, Weston used different kinds of paper. When he was in Mexico, he learned to use platinum and palladium paper. After returning to California, he stopped using these papers because they were hard to find and expensive. He found that Kodak's Azo glossy silver gelatin paper gave him the qualities he liked. He used this paper almost exclusively until he stopped printing.

Edward Weston's Writings

Weston wrote a lot. His "Daybooks" were published in two books, over 500 pages long. He also wrote many articles and comments from 1906 to 1957. He wrote thousands of letters to friends, family, and colleagues.

Weston also kept detailed notes about the technical and business parts of his work. The Center for Creative Photography has most of his writings and documents.

One important idea Weston wrote about was "previsualization." This means the photographer should imagine the final print before taking the picture. He talked about this idea years before Ansel Adams used the term. This idea was very important to his work.

In his "Daybooks," he wrote about how he grew as an artist. His writings, combined with his photos, show how he developed his art. They also show his big impact on future photographers.

Famous Sayings

- "Form follows function." (This means how something looks should be based on what it does.)

- "I am not a technician and have no interest in technique for its own sake. If my technique is adequate to present my seeing then I need nothing more." (He cared more about what he saw than just how he took the picture.)

- "I see no reason for recording the obvious." (He wanted to show things in new ways.)

- "My own eyes are no more than scouts on a preliminary search, for the camera's eye may entirely change my idea." (The camera could show him things he didn't see at first.)

- "This then: to photograph a rock, have it look like a rock, but be more than a rock." (He wanted his photos to show the deeper meaning of things.)

Weston's Lasting Impact

Edward Weston's work is still very valuable. As of 2013, two of his photographs are among the most expensive photographs ever sold. His 1927 photo Nautilus sold for $1.1 million in 2010.

In 1984, Weston was honored by being added to the International Photography Hall of Fame and Museum.

Major Art Shows

- 1970: The Rencontres d'Arles festival in France held a show called "Hommage à Edward Weston."

- 1986–1987: "Edward Weston in Los Angeles" at Huntington Library.

- 1986: "Edward Weston: Color Photography" at the Center for Creative Photography.

- 1989: "Edward Weston in New Mexico" at the Museum of Fine Arts in Santa Fe.

- 2001–2002: "Edward Weston: the Last Years in Carmel" at The Art Institute of Chicago and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

Images for kids

-

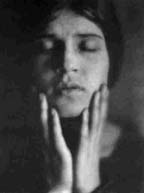

Portrait of Tina Modotti (1922) by Weston

-

Point Lobos (1946) by Weston

See also

In Spanish: Edward Weston para niños

In Spanish: Edward Weston para niños

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |