Hedy Lamarr facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Hedy Lamarr

|

|

|---|---|

Publicity photo (c. 1944)

|

|

| Born |

Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler

November 9, 1914 Vienna, Austria-Hungary

|

| Died | January 19, 2000 (aged 85) Casselberry, Florida, U.S.

|

| Citizenship |

|

| Occupation |

|

| Spouse(s) |

Fritz Mandl

(m. 1933; div. 1937)Gene Markey

(m. 1939; div. 1941)Teddy Stauffer

(m. 1951; div. 1952)W. Howard Lee

(m. 1953; div. 1960)Lewis J. Boies

(m. 1963; div. 1965) |

| Children | 3 |

Hedy Lamarr (born Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler; November 9, 1914 – January 19, 2000) was an amazing Austrian-born American film actress and inventor. She was a big movie star during Hollywood's "golden age." Many people think she was one of the greatest movie actresses of all time.

After starting her film career in Czechoslovakia, she left her first husband and moved to Paris. In London, she met Louis B. Mayer, the head of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer studios. He offered her a movie contract in Hollywood. She became a famous film star after her role in Algiers (1938).

Some of her popular films include Lady of the Tropics (1939) and Boom Town (1940). Her biggest success was playing Delilah in Cecil B. DeMille's Samson and Delilah (1949). She also acted on television. She received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 1960.

During World War II, Hedy Lamarr and composer George Antheil created an important invention. They developed a radio guidance system for Allied torpedoes. This system used a special technology called frequency hopping. It helped prevent enemies from jamming the torpedoes' signals.

Contents

Early Life and Interests

Hedy Lamarr was born Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler in 1914 in Vienna, Austria. She was the only child of Emil and Gertrud Kiesler. Her father was a banker, and her mother was a pianist.

As a child, Hedy loved acting and was very interested in theater and movies. When she was 12, she won a beauty contest in Vienna. She also learned about inventing from her father. He would take her on walks and explain how different technologies worked. This sparked her interest in science and invention.

Starting Her Film Career in Europe

Hedy began taking acting classes in Vienna. One day, she pretended to have a note from her mother and got a job as a script girl at Sascha-Film. She then got a small role as an extra in Money on the Street (1930). Later, she had a speaking part in Storm in a Water Glass (1931).

A famous producer named Max Reinhardt cast her in a play. He was so impressed that he brought her to Berlin. She then got a lead role in No Money Needed (1932). After this, she starred in a film that made her famous around the world.

Hedy also performed in several plays. She played a main role in Sissy, a play about Empress Elisabeth of Austria. Critics praised her performance. She met Friedrich Mandl, a wealthy Austrian arms dealer. He became very interested in her.

Hedy married Mandl on August 10, 1933. She was 18, and he was 33. Hedy later said that Mandl was very controlling. He tried to stop her from acting and kept her almost like a prisoner in their home.

Mandl had connections with leaders of different countries. Hedy went with him to business meetings. There, she met scientists and others working on military technology. These meetings helped her learn about applied science and grow her hidden talent for inventing.

Hedy's marriage became very difficult. In 1937, she decided to leave her husband and her country. She managed to escape and went to Paris. She later wrote about her marriage, saying she felt like an object with no life of her own.

Becoming a Hollywood Star

Meeting Louis B. Mayer

In 1937, Hedy arrived in London. There, she met Louis B. Mayer, who was looking for new actors for MGM. She first turned down his offer of $125 a week. But then she booked a trip on the same ship as him to New York. She impressed him so much that he offered her a $500 a week contract!

Mayer convinced her to change her name to Hedy Lamarr. He chose the name to honor Barbara La Marr, a beautiful silent film star. He brought Hedy to Hollywood in 1938. He promoted her as the "world's most beautiful woman."

Mayer loaned Hedy to producer Walter Wanger for the film Algiers (1938). She starred opposite Charles Boyer. The movie was a huge hit and made her famous. People were amazed by her beauty when she first appeared on screen.

Popular Films

Hedy's second American film was I Take This Woman. It co-starred Spencer Tracy. After this, she made Lady of the Tropics (1939).

A much more popular film was Boom Town (1940). She starred with Clark Gable, Claudette Colbert, and Spencer Tracy. It earned a lot of money. MGM then put Hedy and Gable together again in Comrade X (1940), which was also a success.

Hedy starred with James Stewart in Come Live with Me (1941). She also appeared in Ziegfeld Girl (1941) with Judy Garland and Lana Turner. This film was a big hit.

She made more successful films like Tortilla Flat (1942) and Crossroads (1942). Hedy played Tondelayo in White Cargo (1942), which was a huge success.

She then made The Heavenly Body (1944) and The Conspirators (1944). Her last film under her MGM contract was Her Highness and the Bellboy (1945). She played a princess who falls in love with a New Yorker. It was very popular.

Off-screen, Hedy was quite different from her glamorous image. She often felt lonely and missed her home. She avoided crowds and wondered why people wanted her autograph. People who met her said she was very sophisticated and had a special charm.

Hedy was one of the few European actors who came to America and became a big star. She was very clever and adaptable.

Helping the War Effort

During World War II, Hedy wanted to help the war effort. She was told that she could best help by using her fame to sell war bonds.

She joined a campaign to sell war bonds. She would call a sailor named Eddie Rhodes onto the stage. She would playfully flirt with him and ask the audience if she should kiss him. The crowd would cheer yes. Hedy would say she would kiss him if enough people bought war bonds. After enough bonds were sold, she would kiss him. Then they would go to the next rally.

Later Films

After leaving MGM in 1945, Hedy started her own production company. She made the thriller The Strange Woman (1946).

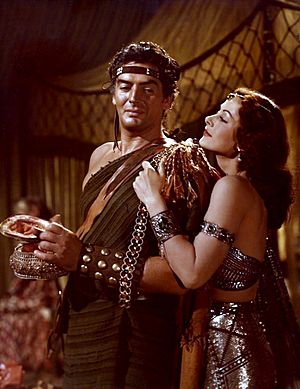

Hedy had her biggest success playing Delilah in Cecil B. DeMille's Samson and Delilah. She starred opposite Victor Mature as the Biblical strongman. This was the highest-earning film of 1950 and won two Oscars.

She returned to MGM for A Lady Without Passport (1950). She also made two popular films at Paramount: Copper Canyon (1950) and My Favorite Spy (1951).

Her career began to slow down. Her last film was the thriller The Female Animal (1958).

Hedy Lamarr: The Inventor

Even though Hedy Lamarr didn't have formal training, she loved to tinker with ideas in her free time. She thought about many things, like a new kind of traffic stoplight. She even tried to make a tablet that would dissolve in water to create a carbonated drink. She said it tasted like Alka-Seltzer!

During World War II, Hedy learned about radio-controlled torpedoes. She realized that enemies could easily jam these torpedoes' guidance systems. She discussed this problem with her friend, the composer and pianist George Antheil. They came up with an amazing idea: a frequency-hopping signal! This signal would jump between different radio frequencies. This would make it very hard for enemies to track or jam the torpedoes.

Antheil figured out how to make this work using a system similar to a player piano. It used a perforated paper tape to control the frequency changes. Hedy hired an engineer to help make the idea real.

Their invention was granted a U.S. patent on August 11, 1942. It was called "Secret Communication System."

In 1997, Hedy Lamarr and George Antheil received the Electronic Frontier Foundation Pioneer Award. They were also given the Bulbie Gnass Spirit of Achievement Bronze Award. These awards recognize people whose creative achievements have greatly helped society. In 2014, Hedy Lamarr and Antheil were honored by being added to the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

Even though the U.S. Navy didn't use their technology right away, the ideas from their work are used today. The principles of frequency hopping are found in modern technologies like Bluetooth and GPS. They are also similar to methods used in Wi-Fi. This important work led to their induction into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 2014.

Later Life

Hedy Lamarr became a citizen of the United States when she was 38, on April 10, 1953.

In the late 1950s, Hedy designed and helped develop a ski resort in Aspen, Colorado.

In the 1970s, Hedy became more private. She was offered many acting jobs, but none interested her. Her eyesight began to fail, and she moved to Miami Beach, Florida, in 1981.

In 1996, a drawing of Hedy Lamarr won a contest for the cover of CorelDRAW software. Her image was on the software boxes for several years. She later settled a disagreement with the company about using her image.

Hedy Lamarr has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 6247 Hollywood Blvd.

In her final years, Hedy mostly communicated with the outside world by telephone. She would talk for many hours a day, but she spent very little time with people in person.

Death and Tributes

Hedy Lamarr passed away in Casselberry, Florida, on January 19, 2000, at the age of 85. Her son, Anthony Loder, spread her ashes in Austria's Vienna Woods, as she wished.

In 2014, a memorial to Hedy Lamarr was unveiled in Vienna's Central Cemetery.

Awards and Honors

- Hedy Lamarr received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 1960.

- In 1939, she was chosen as the "most promising new actress" in a poll.

- In 1951, British moviegoers voted her the year's 10th best actress for her role in Samson and Delilah.

- In 1997, Hedy Lamarr and George Antheil were honored with the Electronic Frontier Foundation's Pioneer Award. Hedy was also the first woman to receive the Invention Convention's BULBIE Gnass Spirit of Achievement Award.

- In 1998, her home country of Austria gave her the Viktor Kaplan Medal.

- In 2006, a street in Vienna was named Hedy-Lamarr-Weg after her.

- In 2014, a quantum telescope in Vienna was named after her.

- Also in 2014, Hedy Lamarr was added to the National Inventors Hall of Fame for her work on frequency-hopping spread spectrum technology.

- On November 9, 2015, Google honored her with a special doodle on her 101st birthday.

- On August 27, 2019, an asteroid was named after her: 32730 Lamarr.

Marriages and Family

Hedy Lamarr was married and divorced six times. She had three children.

- She adopted a child during her marriage to Gene Markey (married 1939–1941).

- She had a daughter and a son with John Loder (married 1943–1947). Her son, Anthony Loder, was featured in a 2004 documentary film about her.

After her sixth and final divorce in 1965, Hedy Lamarr remained unmarried for the rest of her life.

Images for kids

-

Clark Gable and Lamarr in Comrade X (1940)

-

Victor Mature and Lamarr in Samson and Delilah (1949)

See also

In Spanish: Hedy Lamarr para niños

In Spanish: Hedy Lamarr para niños

- Inventors' Day

- List of Austrians

| Stephanie Wilson |

| Charles Bolden |

| Ronald McNair |

| Frederick D. Gregory |