Empress Elisabeth of Austria facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Elisabeth in Bavaria |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

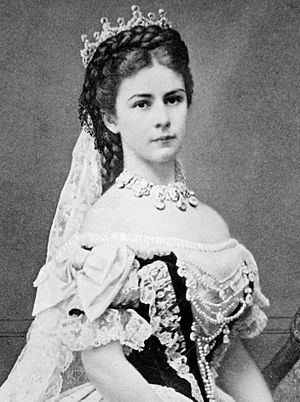

Coronation photograph by Emil Rabending, 1867

|

|||||

| Empress consort of Austria Queen consort of Hungary (more...) |

|||||

| Tenure | 24 April 1854 – 10 September 1898 | ||||

| Coronation | 8 June 1867, Budapest | ||||

| Queen consort of Lombardy-Venetia | |||||

| Tenure | 24 April 1854 – 12 October 1866 | ||||

| Born | Duchess Elisabeth in Bavaria 24 December 1837 Munich, Kingdom of Bavaria |

||||

| Died | 10 September 1898 (aged 60) Geneva, Switzerland |

||||

| Burial | 17 September 1898 Imperial Crypt |

||||

| Spouse | |||||

| Issue |

|

||||

|

|||||

| House | Wittelsbach | ||||

| Father | Duke Maximilian Joseph in Bavaria | ||||

| Mother | Princess Ludovika of Bavaria | ||||

| Signature |  |

||||

Elisabeth of Bavaria (born Elisabeth Amalie Eugenie; December 24, 1837 – September 10, 1898) was also known as Sisi or Sissi. She became the Empress of Austria and Queen of Hungary when she married Emperor Franz Joseph I on April 24, 1854. She held these titles until she was killed in 1898.

Elisabeth was born into the royal Bavarian House of Wittelsbach. She had a relaxed childhood before marrying Emperor Franz Joseph I at age sixteen. The marriage brought her into the very strict Habsburg court life. She found this difficult and was not ready for it.

Early in her marriage, she disagreed with her mother-in-law, Archduchess Sophie. Sophie took over raising Elisabeth's daughters. One of them, Sophie, died as a baby. When Elisabeth gave birth to a son, Crown Prince Rudolf, her position at court improved.

However, the stress affected her health. She often visited Hungary, which had a more relaxed atmosphere. She grew to love Hungary deeply and helped create the dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary in 1867.

In 1889, Elisabeth's only son died in a sad event at Mayerling. The Empress never fully recovered from this loss. She stopped doing court duties and traveled widely by herself. She was very focused on staying young and beautiful. Elisabeth followed a strict diet and wore very tight corsets to keep her waist tiny.

In 1897, her sister, Sophie, died in a fire in Paris. While traveling in Geneva in 1898, Elisabeth was killed by an Italian anarchist named Luigi Lucheni. She was Empress for 44 years, which was the longest of any Austrian empress.

Contents

Becoming an Empress

Early Life as a Duchess

Elisabeth Amalie Eugenie was born on December 24, 1837, in Munich, Bavaria. She was the third child of Duke Maximilian Joseph in Bavaria and Princess Ludovika of Bavaria. Her father was known for being a bit unusual. He loved circuses and often traveled to avoid his royal duties.

The family lived in the Herzog-Max-Palais in Munich during winter. In summer, they stayed at Possenhofen Castle, far from strict court rules. "Sisi" and her brothers and sisters grew up freely. She often skipped lessons to ride horses in the countryside.

A Royal Marriage Proposal

In 1853, Princess Sophie of Bavaria wanted her son, 23-year-old Emperor Franz Joseph, to marry a relative. She arranged for him to meet her sister Ludovika's oldest daughter, Helene ("Néné"). Franz Joseph had never met Helene, but his mother expected him to obey.

Duchess Ludovika and Helene were invited to Bad Ischl, Upper Austria, for the formal marriage proposal. Fifteen-year-old Sisi went with her mother and sister. They arrived late because the Duchess had migraines and had to stop the journey. Their fancy dresses also never arrived.

They were dressed in black because the Bavarian court was in mourning. Black did not suit Helene's dark hair, but it made Sisi's blonde hair look even more striking.

Helene was a quiet and religious young woman. She and Franz Joseph did not feel comfortable together. Instead, Franz Joseph was immediately interested in Sisi. He told his mother he would not marry anyone if he could not marry Elisabeth. Five days later, their engagement was announced.

They married eight months later in Vienna, at the Augustinerkirche, on April 24, 1854.

Life as Empress of Austria

Elisabeth had a free and easy childhood. She was shy and found it hard to get used to the strict rules of the Habsburg court. Within weeks, she started having health problems. She coughed a lot and became scared of narrow or steep stairs.

She was surprised to find out she was pregnant. Her first child, a daughter named Archduchess Sophie of Austria (1855–1857), was born just ten months after her wedding. Her mother-in-law, Archduchess Sophie, took full control of the baby. She even named the child after herself without asking Elisabeth. She did not let Elisabeth breastfeed or care for her own child.

A year later, a second daughter, Archduchess Gisela of Austria (1856–1932), was born. The Archduchess also took this baby away from Elisabeth. Elisabeth felt more unwanted in the palace because she had not given birth to a son.

A Special Connection with Hungary

In 1857, Elisabeth visited Hungary for the first time with her husband and two daughters. This trip deeply affected her. Many historians believe she found a break from the strict Austrian court life in Hungary. It was the first time she met people in Franz Joseph's empire who were independent and spoke their minds. She felt a strong connection to the proud people of Hungary.

Unlike her mother-in-law, who disliked the Hungarians, Elisabeth felt a bond with them. She began to learn Hungarian. In return, the country loved her back. People in Hungary kept her picture on their desks and pianos. Her love for Hungary was returned with great passion.

A Sad Loss

This same trip to Hungary turned tragic. Both of Elisabeth's children became ill. Gisela recovered quickly, but two-year-old Sophie grew weaker and died. It is believed she died of typhus. Sophie's death made Elisabeth, who already had periods of sadness, fall into deep depression. This sadness stayed with her for the rest of her life. She turned away from her living daughter, Gisela, and began to neglect her.

In December 1857, Elisabeth became pregnant for the third time. Her mother hoped this new pregnancy would help her recover.

Focus on Health and Beauty

Elisabeth was quite tall for her time, at 173 cm (5 feet 8 inches). She kept her weight around 50 kg (110 pounds) for most of her life through strict dieting and exercise.

After her daughter Sophie's death, Elisabeth sometimes refused to eat for days. This behavior returned during later periods of sadness. She avoided eating supper with her family. If she did eat with them, she ate very little and quickly. If her weight went over fifty kilos, she would go on a "fasting cure." This meant almost no food at all. She often disliked meat, so she would have beefsteak juice in soup or a diet of milk and eggs.

Elisabeth made her waist seem even smaller by practicing "tightlacing" with corsets. At her thinnest, her waist was only 40 cm (16 inches) around. Her corsets were custom-made in Paris from leather, likely to withstand the extreme lacing. This process sometimes took an hour. Her mother-in-law was annoyed by this extreme thinness, as she wanted Elisabeth to be pregnant often.

Later in life, her waist still measured only 47 – 49.5 cm (18 ½ – 19 ½ inches). She disliked overweight women and passed this view to her youngest daughter.

Elisabeth did not like expensive clothes or the rules that required constant changes of outfits. She preferred simple, single-color riding clothes. She never wore petticoats or other "underlinen" because they added bulk. She was often sewn into her clothes to avoid wrinkles and to highlight her tiny waist.

The Empress had very strict exercise habits. Every castle she lived in had a gym. She had mats and balance beams in her bedroom for morning exercises. She started fencing in her 50s. She was a passionate horsewoman, riding for hours every day. She became one of the best-known female riders of her time. When she could no longer ride due to pain, she walked instead. She made her attendants go on very long walks and hikes in all kinds of weather.

In her last years, Elisabeth became even more restless. She weighed herself up to three times a day. She took steam baths to avoid gaining weight. By 1894, she was very thin, weighing only 43.5 kg (95.7 lbs). Some historians suggest these habits show she had an eating disorder.

Beauty Routines

Elisabeth was known as one of the most beautiful women in 19th-century Europe. She had demanding beauty routines. Caring for her very long and thick hair took at least three hours daily. Her hair was so long and heavy that she often complained it gave her headaches. Her hairdresser, Franziska Feifalik, traveled with her. Feifalik was not allowed to wear rings and had to wear white gloves. After hours of styling, any hairs that fell out had to be shown to the Empress. When her hair was washed with eggs and cognac every two weeks, all other activities were canceled for the day.

During these long grooming sessions, Elisabeth learned languages. She spoke fluent English and French. She also learned modern Greek in addition to Hungarian.

Elisabeth used very little makeup and perfume. She wanted to show off her natural beauty. To keep her skin perfect, she tried many beauty products. These were made either at the court pharmacy or by a lady-in-waiting. She liked "Crème Céleste" and many facial tonics.

Her nighttime routines were also strict. Elisabeth slept without a pillow on a metal bed, believing it helped her posture. She wore a leather facial mask at night, sometimes lined with raw veal or crushed strawberries. She also received massages. She often slept with cloths soaked in violet or cider vinegar around her hips to keep her waist slim. Her neck was wrapped with cloths soaked in special washing water. To keep her skin tone even, she took a cold shower every morning and an olive-oil bath in the evening.

Elisabeth disliked being photographed, especially later in life. She would quickly use a fan or sunshade to avoid having her picture taken.

Marriage and Motherhood

Franz Joseph loved his wife deeply, but their relationship became complicated later on. He was a serious and traditional man, guided by his mother's strict court rules. Elisabeth, however, lived in a different world. She was restless, shy, and emotionally distant from her husband as she got older. She avoided him and her court duties as much as she could. He allowed her travels but always tried to get her to live a more settled life with him.

Elisabeth slept very little. She spent hours reading and writing at night. She even started smoking, which was shocking for women at the time and led to gossip. She was very interested in history, philosophy, and literature. She admired the German poet Heinrich Heine and collected his letters.

She tried to write poetry inspired by Heine. Calling herself Titania, the Fairy Queen from Shakespeare, Elisabeth wrote her private thoughts and wishes in romantic poems. These poems were like a secret diary. Most of her poetry was about her travels, Greek and romantic themes, and funny comments about the Habsburg dynasty. Her love for travel is clear in her own words:

O'er thee, like thine own sea birds

I'll circle without rest

For me earth holds no corner

To build a lasting nest.

Elisabeth was an emotionally complex woman. Perhaps because of the sadness and unusual traits common in her family, the Wittelsbachs, she was interested in helping people with mental illness. In 1871, when the Emperor asked what she wanted for her Saint's Day, she said: "...a fully equipped lunatic asylum would please me most."

Birth of an Heir

On August 21, 1858, Elisabeth finally gave birth to a son and heir, Rudolf (1858–1889). The 101-gun salute announcing his birth in Vienna also meant Elisabeth had more influence at court. This, along with her support for Hungary, made her a good go-between for the Magyars and the emperor. Her interest in politics grew as she got older. She had liberal views and strongly supported the Hungarian side in the empire's conflicts.

Elisabeth personally supported Hungarian Count Gyula Andrássy. There were even rumors that he was her lover. When talks between the Hungarians and the court broke down, Elisabeth helped restart them. During these long discussions, Elisabeth suggested to the emperor that Andrássy become the Prime Minister of Hungary. She strongly urged her husband to work with him.

Elisabeth openly rebelled when she was still prevented from raising and educating her son. Her health became worrying due to nervous attacks, fasting, extreme exercise, and frequent coughing. Doctors feared she had a serious lung problem and advised her to go to Madeira.

Elisabeth used this as an excuse to leave her husband and children. She spent the winter alone. Six months later, she returned to Vienna but immediately had coughing fits and a fever. She ate very little and slept poorly. Doctors again advised a rest cure, this time in Corfu, where she quickly got better. Her illnesses seemed to improve when she was away from her husband and duties.

Her eating habits also caused physical problems. In 1862, her doctor found she had severe anemia and swelling in her feet. She recovered quickly at a spa. Instead of returning home, she spent more time with her family in Bavaria. She returned to Vienna just before her husband's birthday but immediately suffered a bad migraine.

Rudolf was now four years old, and Franz Joseph hoped for another son. Elisabeth's doctor said her health would not allow another pregnancy. Elisabeth continued to escape boredom and court rules through frequent walking and riding, using her health as an excuse. Staying young-looking was also important to her. She believed: "Children are a curse for a woman, for when they come, they drive away Beauty, which is the best gift of the gods."

She was now more defiant towards her husband and mother-in-law. She openly disagreed with them about Rudolf's military education. Rudolf, like his mother, was very sensitive and not suited for court life.

Queen of Hungary

After avoiding pregnancy for a long time, Elisabeth decided she wanted a fourth child. This decision was both personal and political. By returning to her marriage, she helped Hungary gain equal standing with Austria. She felt a strong connection to Hungary.

The Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867 created the dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary. Andrássy became the first Hungarian prime minister. In return, he made sure Franz Joseph and Elisabeth were officially crowned King and Queen of Hungary in June.

As a coronation gift, Hungary gave the royal couple a country residence in Gödöllő, 32 kilometres (20 mi) east of Buda-Pest. The next year, Elisabeth lived mainly in Gödöllő and Buda-Pest. She left her Austrian subjects feeling neglected. They rumored that if her new baby was a son, she would name him Stephen, after Hungary's patron saint.

This issue was avoided when she gave birth to a daughter, Marie Valerie (1868–1924). Marie Valerie was called the "Hungarian child." She was born in Buda-Pest ten months after her parents' coronation and baptized there. Elisabeth was determined to raise this last child herself, and she finally got her way. She poured all her motherly feelings into her youngest daughter. Her mother-in-law Sophie's influence over Elisabeth's children and the court faded. Sophie died in 1872.

Life of Travel

After achieving her goals, Elisabeth did not stay to enjoy them. Instead, she began a life of travel and saw little of her children. She once said, "If I arrived at a place and knew that I could never leave it again, the whole stay would become hell despite being paradise." After her son's death, she ordered a palace built on the Island of Corfu. She named it the Achilleion, after Homer's hero Achilles. After her death, the German Emperor Wilhelm II bought the building. Later, Greece bought it and turned it into a museum.

Newspapers wrote about her love for horse riding, her diet, exercise, and fashion. She often shopped at the Budapest fashion house, Antal Alter.

On her travels, Elisabeth tried to avoid public attention and crowds. She usually traveled secretly, using names like 'Countess of Hohenembs'. Elisabeth also refused to meet other European monarchs if she did not feel like it. On her fast-paced walking tours, which lasted several hours, she was usually with her Greek language teachers or ladies-in-waiting. Countess Irma Sztáray, her last lady-in-waiting, described the Empress as natural, open-minded, and modest. She was a good listener and smart observer.

Almost all of the ten readers who traveled with Elisabeth were in their mid-twenties and from Greece. The most famous was Constantin Christomanos, who later became a playwright. His memories of Elisabeth were banned by the Viennese court.

The Mayerling Incident

In 1889, Elisabeth's life was shattered by the death of her only son, Rudolf. He was found dead with his young lover Baroness Mary Vetsera. This scandal was known as the Mayerling incident, named after Rudolf's hunting lodge in Lower Austria where they were found.

Elisabeth never recovered from this tragedy. She became even more sad. Within a few years, she lost her father, Max Joseph (1888), her son, Rudolf (1889), her sister Duchess Sophie in Bavaria (1897), Helene (1890), and her mother, Ludovika (1892). After Rudolf's death, she was thought to have worn only black for the rest of her life. However, a light blue and cream dress from that time was found in The Hofburg's Sisi Museum. To add to her losses, Count Gyula Andrássy died a year later, in 1890. Elisabeth said, "My last and only friend is dead."

The Mayerling scandal made the public even more interested in Elisabeth. She remained a famous figure wherever she went. She wore long black dresses that could be buttoned up at the bottom. She carried a white leather parasol and a fan to hide her face from curious people.

Elisabeth spent little time in Vienna with her husband. Their letters to each other increased in her last years, and their relationship became a warm friendship. On her imperial ship, Miramar, Empress Elisabeth traveled through the Mediterranean. Her favorite places were Cape Martin on the French Riviera, and Sanremo in Italy. She also liked Lake Geneva in Switzerland, Bad Ischl in Austria (where the imperial couple spent summers), and Corfu. The Empress also visited countries not usually seen by European royals, such as Morocco, Algeria, Malta, Turkey, and Egypt. The Emperor hoped his wife would finally settle down in her palace Achilleion on Corfu. However, Sisi soon lost interest in the beautiful property. Her endless travels became a way for Elisabeth to escape her life and sadness.

Assassination

In 1898, Elisabeth, then 60 years old, traveled secretly to Geneva, Switzerland. This was despite warnings of possible assassination attempts. However, someone from the Hôtel Beau-Rivage revealed that the Empress of Austria was staying there.

At 1:35 p.m. on Saturday, September 10, 1898, Elisabeth and Countess Irma Sztáray de Sztára et Nagymihály, her lady-in-waiting, left the hotel. They walked along the shore of Lake Geneva to catch a steamship for Montreux. The Empress disliked parades, so she insisted they walk without her other companions.

As they walked along the promenade, a 25-year-old Italian anarchist named Luigi Lucheni approached them. He stabbed Elisabeth with a sharpened needle file, which was 4 inches long and had a wooden handle.

Lucheni had originally planned to kill the Duke of Orléans. But the Duke had left Geneva. So, the assassin chose Elisabeth when a Geneva newspaper reported that the elegant woman traveling as "Countess of Hohenembs" was the Empress Elisabeth of Austria.

Six sailors carried Elisabeth back to the Hotel Beau-Rivage on a makeshift stretcher. When they moved her to the bed, she was clearly dead. She was pronounced dead at 2:10 p.m. Elisabeth had been the Empress of Austria for 44 years.

Geneva went into mourning. Elisabeth's body was placed in three coffins: two inner ones of lead and a third outer one of bronze. On Tuesday, before the coffins were sealed, Franz Joseph's representatives arrived to identify the body. The coffin had two glass panels that could be opened to see her face.

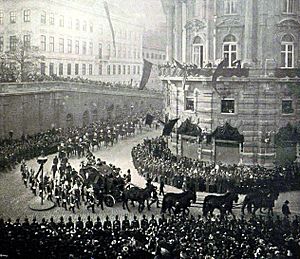

On Wednesday morning, Elisabeth's body was taken back to Vienna on a funeral train. The inscription on her coffin read, "Elisabeth, Empress of Austria.” The Hungarians were angry, so the words, "and Queen of Hungary" were quickly added. The entire Austro-Hungarian Empire was in deep mourning. Many important people followed her funeral procession on September 17 to the tomb in the Capuchin Church.

Legacy

After her death, Franz Joseph created the Order of Elizabeth in her memory.

In the Volksgarten of Vienna, there is a large memorial monument. It features a seated statue of the Empress by Hans Bitterlich. It was dedicated on June 4, 1907.

On the promenade in Territet, Switzerland, there is another monument to the Empress. It was created by Antonio Chiattone in 1902. This town is between Montreux and Chateau Chillon. The inscription mentions her many visits to the area.

Near where she was killed at Quai du Mont-Blanc on Lake Geneva, there is a statue in her memory. It was created by Philip Jackson and dedicated in 1998, 100 years after her death.

Many chapels were named in her honor, linking her to Saint Elisabeth. Various parks, like the Empress Elisabeth Park in Meran, South Tyrol, were also named after her.

Several places where Elisabeth lived are now open to the public. These include her Imperial Hofburg apartment and the Schönbrunn Palace in Vienna. Also, the Hermesvilla in the Vienna Woods, the Imperial Villa in Bad Ischl, the Achilleion on the Island of Corfu, and her summer residence in Gödöllő, Hungary. Her childhood summer home, Possenhofen Castle, now houses the Empress Elizabeth Museum. Her special railway sleeping car is on display at the Technisches Museum in Vienna.

Several places in Hungary are named after her. Two of Budapest's districts, Erzsébetváros and Pesterzsébet, and Elisabeth Bridge are examples.

In the village Gastouri on the Greek island of Corfu, a fountain is named after Elisabeth. The Empress had given the "Fountain under the Sycamores" to the locals. It was officially opened in 1894 and later named "Elisabeth Fountain."

Empress Elisabeth and the Empress Elisabeth Railway (West railway) were recently featured on a special collector coin.

In 1998, Gerald Blanchard stole the Koechert Diamond Pearl, known as the Sisi Star. This 10-pointed star of diamonds with a large pearl was stolen from an exhibit. It was one of about 27 jewel-covered pieces made for her hair by court jeweler Jakob Heinrich Köchert. The Star was found by Canadian Police in 2007 and returned to Austria.

Other statues in memory of Empress Elisabeth were put up in Salzburg and in the garden of the former Hotel Strauch in Feldafing. There are also statues in Budapest and Funchal on Madeira.

Images for kids

-

Empress Elisabeth of Austria in Courtly Gala Dress with Diamond Stars by Franz Xaver Winterhalter, 1865.

-

Memorial statue in Territet.

See also

In Spanish: Isabel de Baviera para niños

In Spanish: Isabel de Baviera para niños

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |