Irish mythology facts for kids

Irish mythology is a collection of amazing stories from Ireland. These tales were first told long ago, even before writing existed. People passed them down by speaking them aloud. Later, during the early Middle Ages, Christian monks wrote some of these myths down. They sometimes changed the stories a bit to fit Christian beliefs. Irish mythology is the best-preserved part of all Celtic mythology.

These myths are usually grouped into different 'cycles' or collections of stories. The Mythological Cycle tells about god-like beings called the Tuatha Dé Danann. These characters are based on Ireland's ancient gods. This cycle also includes other mythical groups like the Fomorians. Important stories here are the Lebor Gabála Érenn (or "Book of Invasions"), which is a legendary history of Ireland, and the Children of Lir.

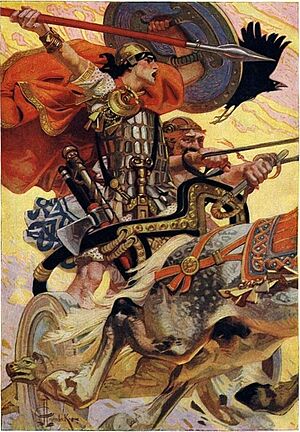

The Ulster Cycle features brave heroes from the Ulaid people. The most famous story in this cycle is the epic Táin Bó Cúailnge ("Cattle Raid of Cooley"). The Fenian Cycle focuses on the adventures of the legendary hero Finn and his group of warriors, the Fianna. A long story from this cycle is the Acallam na Senórach ("Tales of the Elders"). Finally, the Cycles of the Kings includes legends about real and semi-real kings of Ireland. An example is Buile Shuibhne ("The Madness of King Sweeny").

Some mythical stories don't fit into these main cycles. These include echtrai tales, which are journeys to the Otherworld. An example is The Voyage of Bran. There are also Dindsenchas ("lore of places"), which explain how places got their names. Many other myths were likely never written down and are now lost.

Contents

Mythical Beings and Heroes

The Tuatha Dé Danann

The main magical beings in Irish mythology are the Tuatha Dé Danann. This name means "the folk of the goddess Danu." They were also called "god folk" or "tribe of the gods." Early writers described them as powerful kings, queens, warriors, healers, and craftspeople. They had amazing supernatural powers and lived forever.

Some important members of the Tuatha Dé Danann include The Dagda ("the great god"), The Morrígan ("the great queen"), Lugh, Nuada, Aengus, Brigid, and Manannán. They were also believed to control how fertile the land was. Stories say the first people in Ireland had to make friends with the Tuatha Dé Danann to grow crops and raise animals.

These beings live in the Otherworld. However, they often interact with humans. Many are linked to special places in the landscape, especially ancient burial mounds called sídhe. These mounds, like Brú na Bóinne, are thought to be entrances to the Otherworld. The Tuatha Dé Danann can hide themselves using a féth fíada, which is a magic mist.

In some tales, kings gained their right to rule from one of the Tuatha Dé Danann. Or, a king's rule was confirmed by meeting a magical woman from the Otherworld. The Tuatha Dé Danann could also bring bad luck to kings who didn't rule fairly.

Many of the Tuatha Dé Danann were once seen as gods in ancient Irish paganism. For example, Lugh is similar to the Celtic god Lugus. Brigid is like the goddess Brigantia. These beings are not always defined by just one quality. They are more like well-rounded people with special skills, such as magic.

Irish goddesses are often connected to the land, water, and leadership. They are seen as the oldest ancestors of the people. They are like mothers who care for the earth and their descendants. But they are also fierce protectors, teachers, and warriors. The goddess Brigid is linked to poetry, healing, and metalworking. Another figure is the Cailleach, who is said to have lived many lives. Her stories connect her to both land and sea.

Warrior goddesses are often shown in groups of three. They are linked to leadership and sacred animals. They protect warriors on the battlefield. In some stories, they even start and direct wars themselves. The main battle goddesses are The Morrígan, Macha, and Badb. Other warrior women, like Liath Luachra, trained heroes in the Fianna warrior groups. These goddesses can also change into animal forms. For example, Badb Catha is "the Raven of Battle." The Morrígan can turn into an eel, a wolf, or a cow.

The Fomorians

The Fomorians are a group of magical beings. They are often shown as unfriendly and monstrous creatures. At first, people believed they came from under the sea or the earth. Later, they were described as sea raiders, perhaps because of the Viking raids on Ireland. Even later, they were seen as giants.

The Fomorians are enemies of Ireland's first settlers. They also fought against the Tuatha Dé Danann. However, some members of both groups had children together. The Tuatha Dé Danann defeated the Fomorians in the Battle of Mag Tuired. This battle is similar to other ancient myths where gods fight, like the Æsir and Vanir in Norse mythology.

Brave Heroes

Heroes in Irish mythology come in two main types. One type is the lawful hero who protects their community from outsiders. These heroes are human, unlike the gods.

The Fianna were groups of warriors who were seen as outsiders. They were connected to the wild, youth, and special in-between states. Their leader was Fionn mac Cumhaill. The first stories about him date back to the fourth century. These warriors were like aristocrats and protectors. They might spend winters in settled communities. But they lived in the wild during the summers, training young people and offering a place for older warriors. This time in the wild was a transition for young men, from puberty to adulthood. They lived under their own leaders and sometimes followed different gods than the settled communities.

Legendary Creatures

The Oilliphéist is a monster in Irish mythology that looks like a sea serpent. People believed these monsters lived in many lakes and rivers in Ireland. There are legends of saints, especially Saint Patrick, and heroes fighting them.

Mythological Cycle Stories

The Mythological Cycle contains stories about ancient gods and the origins of the Irish people. This cycle is about the main groups who invaded and lived on the island. These groups include Cessair and her followers, the Fomorians, the Partholinians, the Nemedians, the Firbolgs, the Tuatha Dé Danann, and the Milesians.

The most important sources for these stories are the Metrical Dindshenchas (or Lore of Places) and the Lebor Gabála Érenn (or Book of Invasions). Other old writings tell tales like The Wooing Of Étain and Cath Maige Tuireadh (the second Battle of Magh Tuireadh). One of the most famous Irish stories, The Tragedy of the Children of Lir, is also part of this cycle.

The Lebor Gabála Érenn is a legendary history of Ireland. It traces the Irish people's family tree back to before Noah. It tells of several invasions of Ireland by different groups. The fifth group was the Tuatha Dé Danann. They were believed to live on the island before the Gaels (or Milesians) arrived. The Tuatha Dé Danann fought against their enemies, the Fomorians, led by Balor of the Evil Eye. Lugh Lámfada (Lugh of the Long Arm) eventually killed Balor at the second battle of Magh Tuireadh. When the Gaels arrived, the Tuatha Dé Danann went underground. They became the fairy people of later myths and legends.

The Metrical Dindshenchas is a big collection of poems. It explains how important places in Ireland got their names. It shares a lot of key information about the Mythological Cycle's characters and stories. This includes the Battle of Tailtiu, where the Milesians defeated the Tuatha Dé Danann.

By the Middle Ages, the Tuatha Dé Danann were seen less as gods and more as magical, shape-shifting people from a golden age in Ireland. Old texts describe them as kings and heroes from the distant past. However, there is strong evidence that they were once considered gods. Even after they lost their rule over Ireland, characters like Lugh, the Mórrígan, Aengus, and Manannán Mac Lir appear in stories set centuries later. This shows they were immortal.

Ulster Cycle Stories

The Ulster Cycle stories are usually set around the first century AD. Most of the action happens in the provinces of Ulster and Connacht. This cycle includes heroic tales about Conchobar mac Nessa, the king of Ulster, and the great hero Cú Chulainn. Cú Chulainn was the son of Lugh. The stories also feature their friends, lovers, and enemies.

These are the stories of the Ulaid people, who lived in the northeastern part of Ireland. The main setting for these stories is the royal court at Emain Macha (also known as Navan Fort), near the modern town of Armagh. The Ulaid had strong connections with the Irish people who lived in Scotland. Part of Cú Chulainn's training even took place there.

The cycle tells stories of the heroes' births, early lives, training, courtships, battles, feasts, and deaths. It shows a warrior society where fighting mostly involved single combats. Wealth was mainly measured by how many cattle a person owned. These stories are mostly written in prose. The most important story in the Ulster Cycle is the Táin Bó Cúailnge. Other key tales include The Tragic Death of Aife's only Son and Bricriu's Feast. The Exile of the Sons of Usnach, also known as the tragedy of Deirdre, is also part of this cycle.

This cycle is somewhat similar to the Mythological Cycle. Some characters from the earlier cycle reappear. The same kind of shape-shifting magic is common. While some characters, like Medb or Cú Roí, might have once been gods, the characters in this cycle are mortal. They are linked to a specific time and place. If the Mythological Cycle was a Golden Age, the Ulster Cycle was Ireland's Heroic Age.

Fianna Cycle Stories

The Fianna Cycle, also called the Fenian or Ossianic Cycle, is about the brave deeds of Irish heroes. These stories seem to be set around the 3rd century. They mostly take place in the provinces of Leinster and Munster. These stories are different from the other cycles because they have strong links with the Gaelic-speaking people in Scotland. Many texts from Scotland still exist.

They also differ from the Ulster Cycle because they are mostly told in verse (poems). Their style is more like a romance than an epic. The stories are about the actions of Fionn mac Cumhaill and his group of soldiers, the Fianna.

The most important source for the Fianna Cycle is the Acallam na Senórach (Colloquy of the Old Men). This text is found in two old manuscripts from the 15th century and one from the 17th century. The text itself is believed to be from the 12th century. It records conversations between Caílte mac Rónáin and Oisín, who were the last surviving members of the Fianna, and Saint Patrick. This long text has about 8,000 lines. The fact that the manuscripts are from later dates might mean these Fenian stories were told orally for a long time.

The Fianna in the stories were divided into two groups. One was the Clann Baiscne, led by Fionn mac Cumhaill (often called "Finn MacCool"). The other was the Clann Morna, led by Fionn's enemy, Goll mac Morna. Goll killed Fionn's father, Cumhal. So, young Fionn was raised in secret. As a youth, while learning poetry, he accidentally burned his thumb while cooking the Salmon of Knowledge. This allowed him to gain amazing wisdom by sucking his thumb. He became the leader of his group, and many tales are told about their adventures.

Two of the greatest Irish tales are part of this cycle: Tóraigheacht Dhiarmada agus Ghráinne (The Pursuit of Diarmuid and Gráinne) and Oisín in Tír na nÓg. The Diarmuid and Grainne story is one of the few prose tales in this cycle. It is likely the source for the later story of Tristan and Iseult.

The world of the Fianna Cycle is one where professional warriors spent their time hunting, fighting, and having adventures in the spirit world. New members of the group had to know poetry and pass several physical tests. Most of the poems are said to have been written by Oisín. This cycle helps connect the time before Christianity with Christian times in Ireland.

Kings' Cycle Stories

The medieval Irish bards, or court poets, had a duty to record the history and family tree of the king they served. They did this in poems that mixed myths with history. The stories that came from this are known as the Cycle of the Kings. This term was first used in 1946 by an Irish literary critic named Myles Dillon.

The kings in these stories range from the almost completely mythical Labraid Loingsech, who supposedly became High King of Ireland around 431 BC, to the truly historical Brian Boru. However, the most famous story in the Kings' Cycle is Buile Shuibhne (The Frenzy of Sweeney). This 12th-century tale is told in both poetry and prose. Suibhne, the king of Dál nAraidi, was cursed by St. Ronan. He became a strange half-man, half-bird creature. He was forced to live in the woods, running away from other humans. This story has captured the imagination of modern Irish poets.

Other Interesting Tales

Journeys to the Otherworld

The echtrae, or adventures, are stories about visits to the Irish Otherworld. This magical place might be across the sea to the west, underground, or simply invisible to humans. The most famous, "Oisin in Tir na nÓg," is part of the Fenian Cycle. But several other standalone adventures exist. These include The Adventure of Conle and The Voyage of Bran mac Ferbail.

Sea Voyages

The immrama, or voyages, are tales of sea journeys and the amazing things seen on them. These stories might have come from combining fishermen's experiences with elements of the Otherworld. Out of seven immrama mentioned in old writings, only three have survived. These are The Voyage of Máel Dúin, the Voyage of the Uí Chorra, and the Voyage of Snedgus and Mac Riagla. The Voyage of Mael Duin is an early version of the later Voyage of St. Brendan.

Irish Folk Tales

Even though many Irish myths were written down, many stories were also passed down orally. This means people told them through traditional storytelling. Some of these stories have been lost over time. However, some Celtic regions still tell folk tales today.

Monks and scribes helped preserve many folk tales from the bards (poets) who served noble families. When these noble families declined, this tradition of writing down stories stopped. So, the bards passed the stories to their families, and the families continued the oral tradition of storytelling.

In the early 1900s, Herminie Templeton Kavanagh wrote down many Irish folk tales. She published them in magazines and two books. Years after her death, the stories from her books were made into the film Darby O'Gill and the Little People. The famous Irish playwright Lady Gregory also collected folk stories to help preserve Irish history. The Irish Folklore Commission gathered folk tales from the general Irish public starting in 1935.

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |