Robert Rauschenberg facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Robert Rauschenberg

|

|

|---|---|

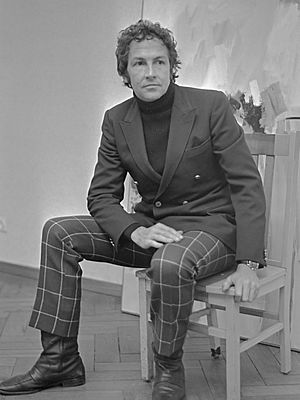

Rauschenberg in 1968

|

|

| Born |

Milton Ernest Rauschenberg

October 22, 1925 Port Arthur, Texas, U.S.

|

| Died | May 12, 2008 (aged 82) Captiva, Florida, U.S.

|

| Education | Kansas City Art Institute Académie Julian Black Mountain College Art Students League of New York |

| Known for | Assemblage |

|

Notable work

|

Canyon (1959) Monogram (1959) |

| Movement | Neo-Dada, Abstract Expressionism |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Awards | Leonardo da Vinci World Award of Arts (1995) Praemium Imperiale (1998) |

Robert Rauschenberg (born Milton Ernest Rauschenberg; October 22, 1925 – May 12, 2008) was an American artist. He was a painter and graphic artist. His early artworks helped start the Pop art movement.

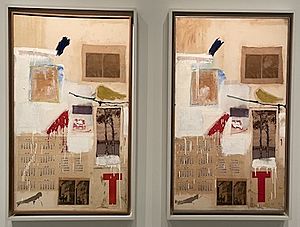

Rauschenberg is famous for his "Combines" (1954–1964). These were artworks that mixed everyday objects with painting. They blurred the lines between painting and sculpture. Rauschenberg also worked with photography, printmaking, and performance art.

He won many awards during his nearly 60-year career. These included the International Grand Prize in Painting at the 32nd Venice Biennale in 1964. He also received the National Medal of Arts in 1993. Rauschenberg lived and worked in New York City and on Captiva Island, Florida, until he passed away in 2008.

Contents

About Robert Rauschenberg's Life

Robert Rauschenberg was born Milton Ernest Rauschenberg in Port Arthur, Texas. His parents were Dora Carolina and Ernest R. Rauschenberg. His father worked for a power company. His parents were very religious. He had a younger sister named Janet.

At 18, Rauschenberg started studying pharmacology at the University of Texas at Austin. But he soon dropped out because the classes were too hard. He didn't know then that he had dyslexia. He also didn't want to dissect a frog in biology class.

In 1944, he joined the United States Navy. He worked in a Navy hospital in California until 1945 or 1946. After the Navy, Rauschenberg studied art at the Kansas City Art Institute. He also went to the Académie Julian in Paris, France. There, he met another art student named Susan Weil. Around this time, he changed his name from Milton to Robert.

In 1948, Rauschenberg and Susan Weil went to Black Mountain College in North Carolina. At Black Mountain, Rauschenberg wanted to learn from Josef Albers. Albers was a famous teacher from Germany. Rauschenberg hoped Albers' strict teaching style would help him be more organized.

Rauschenberg felt he was "Albers' dunce" because he struggled with the strict rules. But he found a better connection with John Cage. Cage was a composer who liked to experiment with music. Cage supported Rauschenberg a lot in his early career. They stayed friends and worked together for many years.

From 1949 to 1952, Rauschenberg studied at the Art Students League of New York. He met other artists like Knox Martin and Cy Twombly there.

Rauschenberg married Susan Weil in 1950. Their son, Christopher, was born in 1951. They separated in 1952 and divorced in 1953. Later in his life, his partner for 25 years was artist Darryl Pottorf.

In the 1970s, he moved to NoHo in New York City. In 1968, Rauschenberg bought his first home on Captiva Island. He made it his main home in 1970. He passed away from heart failure on May 12, 2008, on Captiva Island.

Robert Rauschenberg's Art Style

Rauschenberg's art was sometimes called "Neo-Dadaist." This was a style he shared with painter Jasper Johns. Rauschenberg famously said that "painting relates to both art and life." He wanted his art to exist "in the gap between the two."

Like earlier Dada artists, Rauschenberg questioned what makes something art. He used everyday objects in his work. This was similar to Marcel Duchamp’s famous artwork Fountain (1917), which was a urinal.

At Black Mountain College, Rauschenberg tried many art forms. These included printmaking, drawing, photography, painting, and sculpture. His works often combined these different types of art. He made his Night Blooming paintings in 1951 by pressing pebbles into black paint. That same year, he made full-body blueprints with Susan Weil.

From 1952 to 1953, Rauschenberg traveled in Italy and North Africa with artist Cy Twombly. There, he made collages and small sculptures from things he found. He showed these works in galleries in Rome and Florence. When some didn't sell, he threw them into the river Arno.

When he came back to New York City in 1953, Rauschenberg started making sculptures. He used scrap metal, wood, and string he found in his neighborhood. In the 1950s, he designed window displays for stores like Tiffany & Co. to earn money. He worked with Susan Weil and later with Jasper Johns.

In 1953, Rauschenberg did something very famous. He asked the painter Willem de Kooning for a drawing. Then, with de Kooning's permission, he erased it. This artwork was called Erased de Kooning Drawing. It was a statement about what art could be.

In 1961, Rauschenberg showed an idea as an artwork. He was asked to make a portrait of a gallery owner, Iris Clert. His artwork was a telegram that said, "This is a portrait of Iris Clert if I say so."

By 1962, Rauschenberg started adding found images to his paintings. After visiting Andy Warhol's studio, he began using a silkscreen process. This process is usually used for printing on T-shirts or posters. He used it to put photographs onto his canvases. These silkscreen paintings from 1962 to 1964 made critics link his work to Pop art.

Rauschenberg also liked to use technology in his art. In the 1950s, he put working radios and electric fans into his "Combines." He later worked with a scientist named Billy Klüver. Together, they created "Experiments in Art and Technology" (E.A.T.) in 1966. This group helped artists and engineers work together.

In 1969, NASA invited Rauschenberg to watch the launch of Apollo 11. After this, he made his Stoned Moon Series of lithographs. These combined diagrams from NASA with his own drawings and writing.

From 1970, Rauschenberg worked from his home in Captiva, Florida. He used materials he found nearby, like cardboard and sand. His earlier works showed city scenes, but now he used natural fibers from fabric and paper. He printed on textiles to make his Hoarfrost (1974–76) and Spread (1975–82) series. He also made his Jammer (1975–76) series using colorful fabrics. These were inspired by a trip to Ahmedabad, India, a city known for its textiles.

After 1975, Rauschenberg traveled a lot for his art. In 1984, he started the Rauschenberg Overseas Culture Interchange (ROCI). He mostly paid for this project himself. It was a seven-year tour to ten countries. Rauschenberg took photos and made art inspired by each culture. He often gave an artwork to a local museum.

In the mid-1980s, Rauschenberg started silkscreening images onto different metals. He made many "metal paintings." In the 1990s, he used new technologies like digital inkjet printing. He transferred photos to different surfaces. For his Arcadian Retreats (1996), he printed images onto wet fresco. He also used eco-friendly dyes and water in his printing process.

White, Black, and Red Paintings

In 1951, Rauschenberg created his White Painting series. These were all-white paintings. They were shown in New York in 1953. Rauschenberg used white house paint and rollers to make smooth, plain surfaces. At first, they looked like blank canvases. But composer John Cage said they were like "airports for the lights, shadows and particles." They reflected small changes in the room. Rauschenberg said you could "almost tell how many people are in the room" by looking at them.

Like the White Paintings, his black paintings (1951–1953) were mostly one color. Rauschenberg put black paint on textured backgrounds of newspaper on canvas. Sometimes, you could still see the newspaper underneath.

By 1953, Rauschenberg moved from white and black paintings to his Red Painting series. He thought red was "the most difficult color" to paint with. He dripped, pasted, and squeezed layers of red paint onto canvases. These canvases included fabric, newspaper, wood, and nails. The complex surfaces of the Red Paintings led to his famous "Combine" series.

Combines: Art from Everyday Objects

Rauschenberg collected discarded objects from the streets of New York City. He brought them to his studio and used them in his art. He said he wanted to use the "surprise and the generosity of finding surprises." He believed that when an object was put into art, it became something new.

Rauschenberg thought there was beauty in almost everything. He said, "I really feel sorry for people who think things like soap dishes or mirrors or Coke bottles are ugly." His "Combine" series gave new meaning to everyday objects. He put them into fine art alongside traditional painting materials. The Combines blended painting and sculpture into one artwork. Even after the official "Combines" period (1954-1964), Rauschenberg kept using everyday items in his art.

Some of his first Combines were Charlene (1954) and Collection (1954/1955). In these, he glued objects like scarves, light bulbs, mirrors, and comic strips. One of his most famous Combines is Bed (1955). He smeared red paint across a quilt, sheet, and pillow. He hung it on the wall like a painting. Because the materials were personal, Bed is often seen as a self-portrait.

Some of his other famous Combines include stuffed animals. Monogram (1955–1959) has a stuffed angora goat. Canyon (1959) features a stuffed golden eagle. Even though the eagle was found in the trash, Canyon caused problems with the government. This was because of a law protecting eagles.

Performance and Dance Art

Rauschenberg became interested in dance when he moved to New York in the 1950s. He first saw experimental dance at Black Mountain College. He was part of John Cage's Theatre Piece No. 1 (1952), which is often called the first "Happening."

He started designing sets, lights, and costumes for dancers like Merce Cunningham and Paul Taylor. In the early 1960s, he was involved in dance experiments at Judson Memorial Church. He choreographed his first performance, Pelican (1963), for the Judson Dance Theater. Rauschenberg was good friends with many dancers. His full-time work with the Merce Cunningham Dance Company ended after their 1964 world tour.

In 1966, Rauschenberg created the Open Score performance. This was part of a series called 9 Evenings: Theatre and Engineering. This series helped create "Experiments in Art and Technology" (E.A.T.).

In 1977, Rauschenberg, Cunningham, and Cage worked together again. They created Travelogue (1977), and Rauschenberg designed the costumes and sets. He didn't choreograph his own works after 1967. But he continued to work with other choreographers, like Trisha Brown, for the rest of his career.

Special Art Projects and Commissions

Throughout his career, Rauschenberg designed many posters for causes he believed in. In 1965, Life magazine asked him to create art about a modern "Inferno." He used this chance to show his anger about the Vietnam War. He also included issues like racial violence and environmental problems.

In 1969, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City asked Rauschenberg to create a piece for its 100th birthday. He made his 'Centennial Certificate' based on the museum's original founding document. It included images of famous artworks from the museum.

In 1983, he won a Grammy Award for designing the album cover for Talking Heads' album Speaking in Tongues. In 1986, BMW asked Rauschenberg to paint a full-size BMW 635 CSi car. This was part of the famous BMW Art Car Project. His car was the first to feature reproductions of artworks from the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In 1998, the Vatican asked Rauschenberg to create a work for the year 2000. He made The Happy Apocalypse (1999), a twenty-foot-long model. But the Vatican rejected it. They felt his image of God as a satellite dish was not appropriate.

Important Artworks

Art Shows and Exhibitions

Rauschenberg had his first solo art show in 1951. In 1953, he had his first European show in Italy. In 1954, he showed his Red Paintings and Combines in New York. In 1958, a gallery owner named Leo Castelli had a solo show of Rauschenberg's Combines. The only artwork sold was Bed (1955), which Castelli bought himself. It is now at the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Rauschenberg's first big career show was at the Jewish Museum in New York in 1963. In 1964, he became one of the first American artists to win a major painting prize at the Venice Biennale. A large show of his work traveled across the United States from 1976 to 1978.

In the 1990s, another big show was held at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York (1997). It then traveled to other museums until 1999. An exhibition of his Combines was shown at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (2005). It then traveled to other cities until 2007.

His first show after he passed away was at Tate Modern (2016). It then traveled to the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art until 2017.

Other shows include: Robert Rauschenberg: Jammers, Gagosian Gallery, London (2013); Robert Rauschenberg: The Fulton Street Studio, 1953–54, Craig F. Starr Associates (2014); A Visual Lexicon, Leo Castelli Gallery (2014); Robert Rauschenberg: Works on Metal, Gagosian Gallery, Beverly Hills (2014); Rauschenberg in China, Ullens Center for Contemporary Art, Beijing (2016); and Rauschenberg: The 1/4 Mile at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (2018–2019).

Robert Rauschenberg's Legacy

Rauschenberg strongly believed that art could help change society. The Rauschenberg Overseas Culture Interchange (ROCI) started in 1984. It aimed to encourage talks between countries and improve cultural understanding through art. A ROCI exhibition was shown at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., in 1991. This marked the end of a tour to ten countries.

In 1970, Rauschenberg created a program called Change, Inc. It gave emergency money to visual artists who needed financial help. In 1990, Rauschenberg created the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation (RRF). This foundation works to promote causes he cared about, like world peace, the environment, and helping people.

In 1993, President Bill Clinton gave him the National Medal of Arts. In 2000, Rauschenberg received an award for his artistic contributions to the fight against AIDS.

Today, the RRF owns many of Rauschenberg's artworks. In 2011, the foundation showed "The Private Collection of Robert Rauschenberg." This show featured art from Rauschenberg's own collection. The money raised helped fund the foundation's charity work. The RRF also supports new artists and art groups with grants. It has residency programs in New York and at Rauschenberg's former home in Captiva Island.

In 2013, Complex magazine ranked Rauschenberg's Open Score (1966) as one of the greatest performance art works ever.

Art Sales and Fair Pay for Artists

In 2010, one of Rauschenberg's Combines, Studio Painting (1960‑61), sold for $11 million. In 2019, his silkscreen painting Buffalo II (1964) sold for $88.8 million. This was a new record for his work.

In the early 1970s, Rauschenberg worked to get a law passed in the U.S. Congress. This law would pay artists when their work is resold. He started this effort after a wealthy collector, Robert Scull, sold some of his art for a lot of money. Scull had bought Rauschenberg's paintings Thaw (1958) and Double Feature (1959) for $900 and $2,500. About ten years later, Scull sold them for $85,000 and $90,000.

Rauschenberg's efforts led to the California Resale Royalty Act of 1976. He continued to push for similar laws across the country.

See also

In Spanish: Robert Rauschenberg para niños

In Spanish: Robert Rauschenberg para niños

- Combine painting

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |