Morral affair facts for kids

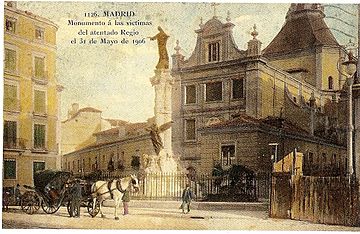

The Morral affair was a shocking event that happened on May 31, 1906, in Spain. It involved an attempt to kill King Alfonso XIII and his new wife, Queen Victoria Eugenie, on their wedding day. The person who tried to do this was named Mateu Morral. He wanted to start a big change in the country. Morral threw a bomb hidden in a bunch of flowers from a hotel window in Madrid as the King's parade passed by. The bomb killed 24 people, including bystanders and soldiers, and hurt over 100 others. Luckily, the King and Queen were not harmed.

After the attack, Morral tried to hide with a journalist named José Nakens. But Morral soon ran away to a town called Torrejón de Ardoz. People in the village noticed him because he seemed out of place. Morral was likely involved in a similar attack on the king a year before this event.

The Morral affair was later used as an excuse to target Francisco Ferrer. He was a teacher who believed in anarchism, a political idea where people govern themselves without a strong government. Ferrer ran a school in Barcelona called Escuela Moderna. This school taught ideas that were against the government, the church, and the military. Morral had worked in the school's library. Ferrer was accused of planning the attack, but he was found not guilty because there wasn't enough proof. However, the government and church still saw him as a threat. The journalist Nakens and two of his friends were sent to prison. They were held partly responsible for what Morral did after he fled Madrid. After a big effort to get them pardoned by the King, they were set free within a year. Nakens' role in this event showed how different groups within the Spanish republican movement had different ideas. Some wanted slow changes, while others wanted a quick revolution. This disagreement later caused problems for the movement.

Contents

Why Did the Morral Attack Happen?

Morral's Background and Beliefs

Mateo Morral's father was a rich businessman. In 1905, after a disagreement about politics, Morral's father gave him some money. Morral then moved to Barcelona. He had traveled a lot for his father's company and had also studied in other countries. Morral disagreed with his father because he supported a group of people called Librepensadores. These were freethinkers, republicans, and freemasons who had strong, radical ideas.

In Barcelona, Morral became close to Francisco Ferrer, a teacher he had met two years earlier. Ferrer was an anarchist, meaning he believed in a society without government. Morral was very interested in Ferrer's Escuela Moderna. This school taught workers to think for themselves and question things. Morral even offered the school a lot of money. Ferrer said no to the money but offered Morral a job in the school's library instead.

Personal Reasons for the Attack

Some people believe that personal feelings and a wish to be famous also played a part in Morral's decision to attack the King. While working at Ferrer's school, Morral developed strong feelings for the head of elementary studies, Soledad Villafranca. However, she did not feel the same way about him.

Soon after, on May 20, 1906, Morral told Ferrer he was going away to get better from an illness. He went to Madrid. There, he walked around the city, went to discussion groups, and sent postcards to Villafranca. In these cards, he wrote about his strong feelings for her and how he felt alone.

A week before the bombing, a park guard found threats against the King carved into a tree. The guard later said he thought Morral had done it. Morral checked into a hotel on Calle Mayor, number 88, using his real name. He paid in advance and asked for a room facing the street. He also asked for a fresh bouquet of flowers every day. On the day of the attack, he asked for a special powder for a stomach problem and wanted to be left alone.

The Wedding Day Attack

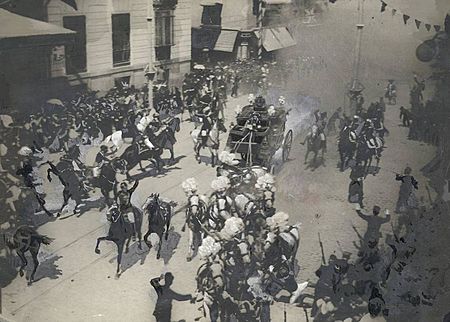

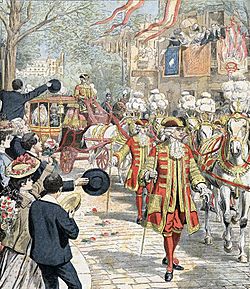

On May 31, 1906, King Alfonso XIII and Queen Victoria Eugenie were returning from their wedding in Madrid. As their carriage passed, Mateo Morral threw a bomb at it. This happened exactly one year after a similar attack on the King's carriage. The bomb was hidden inside a bouquet of flowers. The King and Queen were not hurt at all. However, 24 people, including bystanders and soldiers, were killed, and over 100 more were injured. A British army officer who saw the event said it looked like a war zone. The Queen's wedding dress even got splattered with horse blood. After the attack, the King and Queen were quickly taken to the Royal Palace.

Morral's Escape and Capture

After the bombing, Morral ran away in the confusion. He went to a neighborhood called Malasaña and sought help from the journalist José Nakens. Nakens was known for being against anarchism, but his strong anti-church views attracted people with radical ideas. Historians are not sure if Morral planned to go to Nakens beforehand. However, Morral likely knew Nakens through Ferrer's school, which bought Nakens' anti-church writings.

When Morral arrived at Nakens' printing shop, he told Nakens that he was the one who had thrown the bomb. He reminded Nakens that he had helped another anarchist in the past. Nakens was unsure but agreed to help. He hid Morral at the printing shop and then arranged a place for him to stay for the night. About 90 minutes later, Nakens took Morral to a friend's house. But Morral became suspicious during the night and was gone by morning.

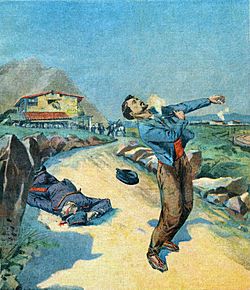

Morral first went to Torrejón de Ardoz to find food and a place to stay. He stood out because of his accent, good looks, and dirty clothes. The local people quickly recognized him. Instead of confronting him directly, they sent someone to tell Madrid about their suspicions. On the second day, local police tried to arrest Morral. He fought back with his gun, shooting a villager and then himself. Morral's body was brought back to Madrid and identified.

Álvaro de Figueroa, 1st Count of Romanones, who was the Spanish Minister of the Interior (responsible for the King's safety), had expected an attack. He and a police officer who watched anarchist activities in France both thought something might happen. This was because the wedding was a very important event, and Madrid was seen as a target by revolutionaries. Romanones had prepared for an attack at the wedding church, San Jerónimo el Real. Morral had originally planned to attack there but changed his mind because of the high security. Once the King and Queen were safely away from the church, Romanones rested, thinking his job was done. He later offered a large reward for information about the attacker. The reward went to the wife of the villager Morral had shot.

What Happened Next?

Francisco Ferrer's Story

Between 1901 and the 1906 bombing attempt, the teacher Francisco Ferrer became very influential. His ideas spread quickly, which worried the Spanish authorities. Ferrer's school taught things that challenged many traditional Spanish ideas. It was against the military, against religion, and against the government. The conservative government and the Catholic church both saw the school as a place where people learned to cause trouble and spread ideas they considered wrong. Ferrer was watched by the police and criticized in newspapers.

The authorities used the 1906 bombing attempt as a reason to stop Ferrer. He was arrested within a week of the attack. He was accused of planning the bombing and of getting Morral involved. Ferrer was put in prison for a year while prosecutors gathered evidence for his trial. An anarchist writer helped with Ferrer's legal defense. He tried to get a famous lawyer to help, but the lawyer refused after seeing the early evidence, believing Ferrer was guilty.

It was not easy for the prosecutors to build a case against Ferrer. They tried to show he was the mastermind by pointing to his connections with anarchism and revolutionary ideas. They suggested that Ferrer encouraged Morral's rebellious thoughts and even told Morral to go to Nakens. However, just days before the bombing, Ferrer and Nakens had exchanged letters. Nakens, who was against anarchism, had turned down an offer from Ferrer to write books for his school. Even though they were polite, Nakens saw himself as an enemy of anarchism. Ferrer insisted that Nakens keep the money, which might have been a bribe. The court was not convinced by this evidence that there was a conspiracy.

Ferrer said he was innocent. He told investigators that he and Morral did not interact much. He also said he did not know Morral was a revolutionary or even in Madrid. The court found that the evidence against Ferrer was not strong enough, so they found him not guilty. However, they did criticize Ferrer's character and his political activities. They said his actions were morally wrong but allowed under the Spanish Constitution's freedom of speech.

Support from other countries also helped Ferrer get released. Anarchists and people who believed in rational thinking said his treatment was like the old Spanish Inquisition. While Ferrer was in jail, a republican leader helped manage his money. With these funds, he started newspapers dedicated to getting Ferrer and Nakens released. Some people said Ferrer was known for being against political violence. But historian Paul Avrich said that Ferrer was a strong anarchist who believed in direct action and understood the importance of political violence.

Historians still disagree about Ferrer's exact role in the bombing attempt. One historian, based on police records, believed Ferrer provided money and explosives and planned both bombing attempts to start a revolution. However, police documents can sometimes be unreliable. In this case, the police had already tried to accuse Ferrer twice before, without success. And the same documents used by the historian were not enough to convict Ferrer at his trial. Ferrer had, however, introduced Morral to other radical people in Barcelona. Some evidence suggests that Ferrer introduced Morral to someone who knew about bombs. It's also possible that Ferrer and another leader planned an attack on the King to cause instability and a revolution. Morral also had access to many revolutionary writings at the school. Historian Paul Avrich wrote that "unless new clear evidence is found, Ferrer's role in the Morral affair remains a question."

Ferrer's school was shut down by the government within weeks of his arrest because of the Morral affair. Some conservative politicians in the Spanish parliament also asked to close all non-religious schools, but this request was denied.

Even though Ferrer was found not guilty, the police still believed he was guilty. After he was released from prison in June 1907, Ferrer continued to support rational education and workers' rights. But in August 1909, he was arrested again. He was accused of leading a week of protests and rebellion known as Tragic Week. While he probably took part in the events, he was not the main planner. The trial that followed, which ended with him being executed by a firing squad, is often remembered as an unfair trial. Historian Paul Avrich called it "judicial murder." It was seen as a way to silence someone whose ideas were dangerous to the existing system, perhaps as revenge for not being able to convict him in the Morral affair.

José Nakens' Experience

On the day Morral died, the journalist José Nakens published an article in his newspaper, El Motín. In it, he spoke out against the bombing and terrorism in general. He did not mention Morral or that he had hidden Morral. He was arrested within a week. The next day, he published a full explanation of his actions in two other newspapers. He repeated that he was against anarchism and called Morral's attack cowardly. He said his brief help to Morral was a mistake, but he did it because he wanted to help a fellow human.

The decision in Nakens' case was made easily. The court believed Nakens had no connection with Morral before the attack. However, they found that his actions to help Morral were more planned than just a quick mistake. They argued that this help led to the death of the villager in Torrejón. Because of this, Nakens was sentenced to nine years in prison. He also had to pay money to the Royal family, the military, and the families affected by the bombing. Nakens' friends, Bernardo Mata and Isidro Ibarra, were also jailed. They only had half of their prison time reduced.

While in Madrid's Cárcel Modelo prison, Nakens became a supporter of prison reform. A campaign started to get him pardoned. He regularly wrote reports in a republican newspaper about the need for more humane prison conditions. This helped improve his reputation with people who had been upset by him hiding Morral. After a big effort involving letters, newspaper articles, and statements from prison officials, Nakens and his friends were pardoned in May 1908.

Other People Involved

On the afternoon of the attack, Ferrer and another republican leader, Alejandro Lerroux, were both waiting for news from Madrid. They were sitting at different tables in the same café in Barcelona. Lerroux also said he was not involved in or aware of the plot. However, he had followers ready to attack Montjuïc Castle. Lerroux's situation actually improved after the affair. Before, he had lost political support, his newspaper, and was struggling financially. But afterwards, he had money and managed Ferrer's estate.

What We Learned from the Affair

Events like the Morral affair showed that Spanish republicans could get a lot of public support through exciting political events. This was important at a time when people were not very interested in formal politics.

The affair also highlighted disagreements within the Spanish republican movement. These disagreements later caused problems for their identity. Nakens, for example, quickly moved away from the idea of slow changes that older republicans believed in. Both republican groups found it hard to work together. The affair even seemed to favor the more moderate republicans, who criticized the radical young republicans. This made Nakens seem unstable by comparison. This split seemed to speed up the coming revolution.

Looking back, historian Enrique Sanabria suggests that Nakens' decision to hide Morral was a sad lesson. It showed his willingness to work with revolutionaries, which later made his more moderate republican friends distance themselves from him. Nakens might have been short-sighted to think that his ideas of equality, democracy, and cultural change would not appeal to the left-wing groups he wanted to avoid. His popularity among anarchists and radicals showed that being against the church was a common idea that brought different left-wing groups together. However, for republicans like Nakens, being against the church was linked to nationalism, but for anarchists and socialists, it was not always. Nakens "became a victim" after the affair because he could not attract workers while also accepting their revolutionary politics.