Constitution of Spain facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Spanish Constitution |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Created | 31 October 1978 |

| Ratified | 6 December 1978 |

| Date effective | 29 December 1978 |

| System | Parliamentary monarchy |

| Branches | 3 |

| Chambers | Bicameral |

| Executive | Government |

| Amendments | 2 |

| Last amended | 27 September 2011 |

| Location | Congress of Deputies |

| Author(s) | |

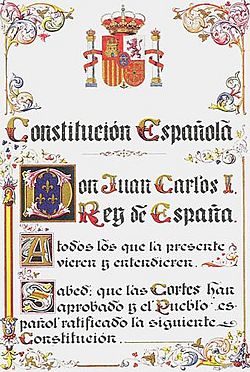

The Spanish Constitution (Spanish: Constitución española) is the most important law in Spain. It's like a rulebook that explains how the country should be run. This Constitution was approved by the Spanish people in a special vote in 1978. It marked the end of a long period of dictatorship and the beginning of Spain's journey to becoming a modern democracy.

This Constitution became official three years after the death of Francisco Franco, who was a military dictator for almost 40 years. Spain has had many constitutions before, but this one, along with the 1931 Constitution, is considered truly democratic. King Juan Carlos I approved it on December 27, 1978. It was then published and became law on December 29, 1978. This was a huge step for Spain, changing it from a dictatorship to a democratic country.

The change to democracy was a careful process. Instead of completely getting rid of the old system, Spain slowly changed its laws and institutions. King Juan Carlos I helped guide this transformation. The Constitution was written and debated by a special group of elected representatives. Once approved, it replaced all the old laws from Franco's time. The new Constitution also took ideas from older Spanish laws and other European countries.

The Constitution has an introduction and ten main parts, plus other important sections. It talks about people's basic rights, the role of the King, how the government works, and how justice is handled. It also explains how Spain is organized into different regions.

Contents

- Understanding the Spanish Constitution

- How the Constitution Was Made

- What's Inside the Constitution

- The Preamble: A Promise to the People

- Preliminary Title: Spain's Core Identity

- Part I: Your Rights and Duties

- Part II: The King's Role

- Part III: The Parliament (Cortes Generales)

- Part IV: The Government

- Part V: Parliament and Government Working Together

- Part VIII: How Spain is Organized (Territorial Model)

- Part X: Changing the Constitution

- Changes Made to the Constitution

- Proposed Changes

- See also

Understanding the Spanish Constitution

The Spanish Constitution is the main law that guides how Spain works. It sets out the rules for everyone, from the government to every citizen.

What the Constitution Says About Spain

Article 1 of the Constitution explains what Spain is all about.

- Article 1.1 says Spain is a "social and democratic State." This means it cares about its people and is run by them. It values freedom, fairness, equality, and different political ideas.

- Article 1.2 explains that the power of the country comes from the Spanish people. They are the ones who decide how the country is governed.

- Article 1.3 states that Spain is a "parliamentary monarchy." This means it has a King or Queen, but the real power is with the elected Parliament and government.

How the Constitution is Organized

The Constitution is divided into different sections, called "Parts" (or Títulos in Spanish).

- Introduction (Preliminary Title): This sets the main ideas, like Spain being a social and democratic state.

- Part I: Fundamental Rights and Duties: This is about the basic rights and responsibilities of everyone in Spain. These rights are very important and protected by law.

- Part II: The Crown: This part explains the role of the King or Queen in Spain.

- Part III: The Cortes Generales: This describes Spain's Parliament, which makes the laws.

- Part IV: The Government: This section talks about the executive branch, which runs the country.

- Part V: Government and Parliament Relations: This explains how the government and Parliament work together.

- Part VI: The Judiciary: This part describes the court system and how justice is given out.

- Part VII: Economy and Finances: This section covers how the country's money and economy are managed.

- Part VIII: Territorial Organization: This explains how Spain is divided into different regions that have some self-governance.

- Part IX: The Constitutional Court: This describes the special court that makes sure all laws follow the Constitution.

- Part X: Constitutional Amendments: This explains how the Constitution can be changed.

How the Constitution Was Made

Spain's journey to its current Constitution started long ago. After the dictator Francisco Franco died in 1975, Spain began its move towards democracy.

Drafting the Constitution

In 1977, a general election was held to choose people who would write the new Constitution. A group of seven people, known as the "Fathers of the Constitution," were chosen from these elected members. They represented different political groups in Spain. Their job was to create the first draft of the Constitution.

The seven "Fathers" were:

- Gabriel Cisneros

- José Pedro Pérez-Llorca

- Miguel Herrero y Rodríguez de Miñón

- Miquel Roca i Junyent

- Manuel Fraga Iribarne

- Gregorio Peces-Barba

- Jordi Solé Tura

A famous writer, Camilo José Cela, helped to make the language of the Constitution clear and precise.

Approval of the Constitution

The Parliament approved the Constitution on October 31, 1978. Then, the Spanish people voted on it in a special referendum on December 6, 1978. A huge majority, 91.81% of voters, said "yes" to the new Constitution. King Juan Carlos I officially approved it on December 27. It became law on December 29, 1978. Since then, December 6 has been a national holiday in Spain, called Constitution Day.

What's Inside the Constitution

The Constitution has 169 articles, plus other important rules. It also officially cancelled several old Spanish laws, especially those from the time of Franco's dictatorship.

The Preamble: A Promise to the People

The Preamble is like an introduction that states the goals of the Constitution. It was written by Enrique Tierno Galván. It says that the Spanish Nation wants to create a fair, free, and safe society. It promises to:

- Make sure democracy works well.

- Build a country where laws are fair and represent the people's will.

- Protect the human rights, cultures, languages, and traditions of all Spaniards.

- Help culture and the economy grow so everyone can have a good life.

- Create an advanced democratic society.

- Work with other countries for peace and cooperation.

Preliminary Title: Spain's Core Identity

This section defines Spain's basic nature.

- Section 1: Spain is a social and democratic country where laws are followed. It values freedom, fairness, equality, and different political ideas. The power comes from the Spanish people, and the government is a parliamentary monarchy (with a King but run by elected officials).

- Section 2: The Constitution says Spain is one nation, but it also respects and protects the right of its different regions and "nationalities" to govern themselves. This means Spain is a bit like a federal system, with regions having different levels of self-rule.

Part I: Your Rights and Duties

This part (Sections 10 to 55) lists the fundamental rights and duties of people in Spain. These rights are very broad and important. They are protected by law and can even be expanded in the future. These rights are for everyone and also guide how public authorities should act.

Chapter One: Spaniards and Foreigners

This chapter talks about who gets constitutional rights.

- Section 11 says how Spanish nationality is handled.

- Section 12 sets the age of adulthood in Spain at 18.

- Section 13 explains that foreigners have public freedoms according to laws and international agreements.

Chapter Two: Important Rights and Freedoms

This chapter starts with Section 14, which says everyone is equal before the law.

- Section One

- Core Rights and Freedoms

Sections 15 to 29 list very important rights and freedoms. These are very hard to change or remove from the Constitution. If these rights are violated, people can ask a court for help.

- Individual rights include the right to life, freedom of thought, freedom and safety, honor, privacy, and freedom of movement. It also includes freedom of speech.

- Group rights include the right to gather peacefully, the right to form groups, the right to vote, the right to education, and the right to strike.

- Fair legal process is also covered, meaning everyone has the right to a fair trial.

- Section Two

- Other Rights and Responsibilities

Sections 30 to 38 list other rights and duties.

- Section 30 used to include military duties, but this is no longer active.

- Section 31 talks about a fair tax system.

- Section 32 covers family law.

- Other sections mention the right to own property, to create non-profit groups, to work, to form professional groups, and to bargain collectively. It also supports a market economy with some government planning.

Chapter Three: Guiding Principles for Society

Sections 39 to 52 explain the ideas behind Spain's welfare state. This means the government aims to ensure everyone has effective freedom and equality. It includes rules for public pensions, social security, public healthcare, and cultural rights.

Chapter Four: Protecting Your Rights

This chapter explains how fundamental rights are protected.

- Section 53 says that laws about these rights must respect their core meaning.

- Section 54 calls for an Ombudsman (Defensor del Pueblo). This person checks on government actions and can help protect citizens' rights.

- If your rights are violated, you can go to court. After that, you can even make a special appeal to the Constitutional Court. This extra protection helps ensure fair legal processes.

Part II: The King's Role

Part II of the Constitution explains the role of the King or Queen, called "The Crown."

- Article 56 says the monarch is the head of state and represents Spain's unity. The King's main job is to ensure that the country's institutions work properly. The King also represents Spain in other countries. The King's official title is "King of Spain," but he can use other historical titles.

Royal Immunity

The King of Spain cannot be sued or prosecuted in court. This means the King is protected from legal action. This is because the King has important duties given by the Constitution, and he must be able to perform them without fear of legal trouble.

Countersigning (Refrendo)

The King has executive power, but he is not personally responsible for his actions. This is because other people, usually the Prime Minister or other ministers, take responsibility for the King's actions. This is called refrendo or "countersigning." All the King's actions must be countersigned by someone else. Without this, the King's actions are not valid. There are only two things the King can do without countersigning:

- Managing the Royal House (like hiring staff).

- His will, which explains how his personal belongings are distributed.

King's Duties in Spain

Article 62 lists the King's duties, which are mostly symbolic.

- The King approves and announces laws passed by the Parliament.

- He also formally calls and dissolves Parliament and calls for elections or referendums.

- The King proposes a candidate for Prime Minister. He often meets with political leaders to help form a government. If Parliament approves a candidate, the King officially names them Prime Minister.

- The King also formally appoints government members suggested by the Prime Minister.

- The King has the right and duty to be informed about all state matters. He can also lead government meetings if the Prime Minister invites him.

- The King formally issues government decrees and grants honors.

- He is the supreme head of the Armed Forces of Spain, but the government holds the real power.

- The King also supports royal academies and other organizations.

Who Becomes King or Queen

Article 57 explains how the Crown is passed down. It follows a system where the oldest son of King Juan Carlos I and his family (the Bourbon dynasty) inherits the throne. The heir to the throne is called the Prince or Princess of Asturias. Other children are called Infantes or Infantas.

- If someone in line for the throne marries without the King's or Parliament's approval, they and their children lose their right to the Crown.

- If there are no more people in the royal line, Parliament decides who will be the new King or Queen.

- Any changes to the succession, like a King giving up the throne, must be made official by a special law. For example, when King Juan Carlos abdicated in 2014, a law was passed to make his son, Felipe VI, the new King.

Regency: When the King is Too Young

Article 59 explains what happens if the King or Queen is too young to rule. This is called a Regency.

- If the King is a minor, his mother or father becomes the regent. If they are not available, the oldest relative who is an adult and next in line for the throne becomes regent.

- If the King becomes unable to rule, Parliament can declare him incapacitated. Then, the Prince or Princess of Asturias becomes regent if they are an adult.

- If there's no one else, Parliament appoints a regent or a group of three to five people called the Council of Regency. The regent must be Spanish and an adult.

- Article 60 says that the King's guardian (the person who takes care of him if he's a minor) cannot be the same person as the regent, unless it's the King's parent. The guardian also cannot hold any political office.

Part III: The Parliament (Cortes Generales)

Part III (Sections 66 to 96) describes the Cortes Generales, which is Spain's Parliament. It has two parts:

- The Congress of Deputies (the lower house).

- The Senate of Spain (the upper house).

The Congress of Deputies has more power than the Senate.

The Parliament makes laws, approves the country's budget, and checks on the government. It also appoints members to important courts and bodies like the Constitutional Court and the Ombudsman. The Parliament also has a say in who becomes King or Queen.

The Parliament works in full sessions or in smaller groups called Commissions. These Commissions study bills and other matters.

Congress of Deputies

Section 68 says the Congress of Deputies has between 300 and 400 members. These members are elected by all citizens in free and secret votes. Each province and the cities of Ceuta and Melilla get at least two seats, and the rest are given based on population.

Senate

Section 69 describes the Senate as an upper house that represents the different regions. Some Senators are elected directly by citizens, and others are chosen by the regional parliaments. The Senate's powers are less than those of the Congress.

Part IV: The Government

Section 97 gives the Government of Spain the power to run the country. This includes managing domestic and foreign policy, the military, and public services.

Section 98 states that the Government includes the Prime Minister, any Deputy Prime Ministers, and other ministers. The Prime Minister leads the government and coordinates everyone's work.

Section 99 explains how the Prime Minister is chosen. After an election, the King meets with political leaders and suggests a candidate. The candidate needs to win a vote in the Congress of Deputies. If they don't get enough votes the first time, they can try again two days later with a simpler majority. If no one can form a government within two months, new elections are called.

Section 100 says that the King appoints and dismisses ministers based on the Prime Minister's suggestions.

Section 101 explains when the Government is dismissed, such as after an election, if it loses Parliament's support, or if the Prime Minister resigns or dies. A dismissed government continues to manage things until a new one is formed.

Part V: Parliament and Government Working Together

Article 115 talks about when the Parliament (Congress, Senate, or both) can be dissolved. This needs the King's approval, and a date for new elections must be set. Parliament cannot be dissolved during a no-confidence vote.

Article 116: Special Situations

This article describes three special situations for the country:

- State of Alarm: The government can declare this for up to 15 days in emergencies. Parliament must be informed and approve any extensions. This was used during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- State of Emergency: The government can declare this for up to 30 days with Parliament's approval. It can be extended.

- State of Siege (Martial Law): This is declared by a large majority in the Congress of Deputies, only if the government proposes it. It determines the area, length, and rules.

During any of these states, Parliament cannot be dissolved. If Parliament is dissolved or its term ends, a special committee takes over its powers.

Part VIII: How Spain is Organized (Territorial Model)

Article 143: Self-Government for Regions

Section 1 says that provinces with shared history, culture, and economy, as well as island territories, can become "Autonomous Communities" and govern themselves. This is based on the right to self-government mentioned in Article 2 of the Constitution.

The Spanish Constitution is special because it includes rules for "social rights." It calls Spain a "Social and Democratic State." However, these social rights (like the right to good housing or healthcare) are seen more as guiding principles for the government's economic policy, rather than rights you can directly claim in court like other individual rights.

The Constitution also recognizes the right to adequate housing, jobs, social welfare, health protection, and pensions. Thanks to the influence of the Communist Party of Spain, the Constitution also allows the government to intervene in private companies for the public good and helps workers have a say in production.

Article 155: Government Intervention in Regions

This article is similar to a rule in Germany's basic law.

- Section 1: If a self-governing region doesn't follow its duties under the Constitution or laws, or harms Spain's general interest, the government can take necessary steps to make the region comply.

- Section 2: To do this, the government can give instructions to all authorities in that self-governing region.

This article was used in October 2017 when the Senate voted to apply Article 155 to Catalonia. This gave the Spanish Prime Minister the power to take direct control of Catalonia after its Parliament declared independence.

Part X: Changing the Constitution

There are two ways to change the Spanish Constitution. The Government, the Congress of Deputies, or the Senate can suggest changes. Regional Parliaments can also propose changes to the Congress or the Government.

The Constitution has been changed only twice: in 1992 and 2011. Both times, the changes were approved without needing a public vote (referendum).

Normal Changes

A change needs to be approved by a three-fifths majority in both the Congress of Deputies and the Senate. If they disagree, a special committee tries to find a solution. If that doesn't work, the Congress can still pass the change with a two-thirds majority, as long as the Senate approved it with a simple majority. Also, a small group of deputies or senators can ask for the change to be put to a public vote within 15 days.

Big Changes (Entrenched Provisions)

Some parts of the Constitution are very important and hard to change. These include the Introduction, the section on Fundamental Rights and Public Freedoms, and the section on the Crown. To change these parts, a much stricter process is needed, similar to adopting a whole new constitution:

- Two-thirds of each house (Congress and Senate) must approve the change.

- New elections must be held right away.

- Two-thirds of each new house must approve the change again.

- Finally, the change must be approved by the people in a public vote (referendum).

Changes Made to the Constitution

The Constitution has been changed twice.

- The first change was in 1992. It allowed citizens of the European Union to vote and run in local elections in Spain, as agreed in the Maastricht Treaty.

- The second change was in 2011. It added a rule to Article 135 about keeping the government's budget balanced and limiting debt.

The Constitution currently says the death penalty can only be used by military courts during wartime. However, the death penalty has been removed from military law, so it's no longer used at all. Some groups, like Amnesty International, want the Constitution to be changed to clearly say the death penalty is completely abolished in all cases.

Other groups, like Amnesty International Spain, Oxfam Intermón, and Greenpeace, started a campaign in 2015. They want to change Article 53 to give the same strong protection to economic, social, and cultural rights as to rights like life or freedom. They also want 24 other changes to protect human rights, the environment, and social fairness.

Changes to Regional Laws (Statutes of Autonomy)

The "Statutes of Autonomy" are like mini-constitutions for Spain's different regions. They are very important for how the country is structured. Attempts to change some of these statutes have caused debates.

For example, a plan by the Basque president to change the status of the Basque Country was rejected by the Spanish Parliament. They said it was like trying to change the Constitution itself.

The 2005 change to the Autonomy Statute of Catalonia also caused a lot of discussion. Some argued it went against the spirit of the Constitution, especially regarding "solidarity between regions." The People's Party even took it to the Constitutional Court.

Many politicians believe that changes to these regional statutes should follow the Constitution more closely. They worry that too many new powers for regions could harm the constitutional system. For instance, some regions want specific amounts of state investment based on their economy or population. If every region had such demands, it would be impossible to manage the national budget. Also, some regions have tried to claim exclusive control over rivers flowing through their land, which affects other regions. These issues are often debated in the Constitutional Court.

Proposed Changes

Other Proposed Amendments

In May 2021, the Spanish government suggested changing Article 49. They want to replace the word disminuidos (meaning "physically diminished") with personas con discapacidad ("persons with disability"). This change would use more people-first language and align with international agreements on the rights of people with disabilities. However, this change has not yet received enough support from other political parties.

See also

- List of constitutions of Spain

- Constitutional economics

- Constitutionalism

- Rule according to higher law

In Spanish: Constitución española de 1978 para niños

In Spanish: Constitución española de 1978 para niños

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |