John O'Hara facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

John O'Hara

|

|

|---|---|

O'Hara in 1945

|

|

| Born | January 31, 1905 Pottsville, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | April 11, 1970 (aged 65) Princeton, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Genre | Short story, drama, essay |

| Notable works |

|

John Henry O'Hara (born January 31, 1905 – died April 11, 1970) was a very productive American writer. He wrote many short stories and helped create the unique style of short stories found in The New Yorker magazine.

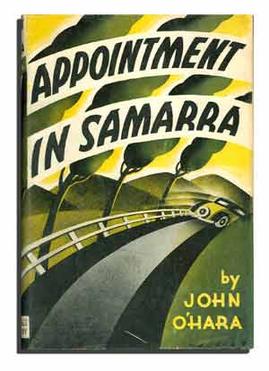

Before he turned 30, O'Hara became a best-selling novelist. His popular books included Appointment in Samarra and BUtterfield 8. Some people think O'Hara is one of the most important American writers of the 20th century. However, his work is not often studied in colleges today. This is partly because he didn't want his stories in books used for teaching.

After World War II, O'Hara's books sold very well. Many of his novels appeared on the top ten best-selling fiction lists. These included A Rage to Live (1949) and Ten North Frederick (1955). Five of his books were even made into popular movies in the 1950s and 1960s.

Even with his success, some people didn't like O'Hara. This was due to his strong personality and his political views. After O'Hara passed away, writer John Updike said that O'Hara wrote so much that people couldn't fully appreciate him. Updike hoped that people would later "marvel at him all over again."

Contents

John O'Hara's Early Life and School

John O'Hara was born in Pottsville, Pennsylvania. His family was wealthy and Irish-American. Even though they were well-off, O'Hara felt like an outsider sometimes. This was because his Irish-Catholic background was different from the mostly WASP society around him. This feeling of being an outsider often appeared in his writing.

He went to secondary school at Niagara Prep in Lewiston, New York. He was chosen as the Class Poet for his graduating class of 1924. Around that time, his father died. This meant O'Hara could no longer afford to go to Yale, his dream college. This sudden change in his family's money and social standing affected O'Hara deeply. It made him very aware of social classes, which became a key part of his stories.

Brendan Gill, who worked with O'Hara at The New Yorker, said O'Hara really wished he had gone to Yale. O'Hara knew everything about colleges and prep schools. The famous writer Ernest Hemingway even joked that someone should start a fund to send O'Hara to Yale. As O'Hara became more famous, he hoped Yale would give him an honorary degree. But Yale didn't give him one, partly because he asked for it directly.

O'Hara's Writing Career and Reputation

John O'Hara started his career as a reporter for different newspapers. He then moved to New York City and began writing short stories for magazines. Early on, he also worked as a film critic, a radio host, and a public relations agent.

In 1934, O'Hara published his first novel, Appointment in Samarra. The famous writer Ernest Hemingway praised it, saying O'Hara "knows exactly what he is writing about." After Samarra, O'Hara wrote BUtterfield 8. This book was based on a real-life event involving a young woman whose death in 1931 was widely talked about.

Over 40 years, O'Hara wrote many novels, novellas, plays, and screenplays. He also wrote over 400 short stories, mostly for The New Yorker magazine. During World War II, he worked as a correspondent in the Pacific. After the war, he continued writing screenplays and novels. These included Ten North Frederick, which won the 1956 National Book Award. He also wrote From the Terrace (1958), which he thought was his best novel. Later in his life, he became a newspaper columnist.

Many of O'Hara's stories are set in Gibbsville, Pennsylvania. This town is a fictional version of his hometown, Pottsville, in the anthracite region of the United States. He named Gibbsville after his friend and editor at The New Yorker, Wolcott Gibbs. Other stories were set in New York or Hollywood.

O'Hara received the most praise for his short stories. He wrote more stories for The New Yorker than any other writer. He published seven collections of stories in the last ten years of his career. He said these stories came easily to him. Charles McGrath, a former editor at The New Yorker, praised O'Hara's stories for their "lightness and brevity." He said they often reveal something important through hints, showing "a sense of speed and economy." Brendan Gill, who worked with O'Hara, called him "among the greatest short-story writers." O'Hara himself once said, "No one writes them any better than I do."

Even though his books were popular, some of O'Hara's longer novels are not as highly regarded by literary experts. Some critics believe that the endings of his novels were sometimes rushed. Part of the criticism of O'Hara's writing came from people disliking him personally. They found him too proud and focused on his social status. They also didn't like his politically conservative newspaper columns later in his career.

In 1949, O'Hara left The New Yorker after a very harsh review of his novel A Rage to Live. His colleague Brendan Gill wrote the review, calling the book a "catastrophe." This review shocked the literary world. O'Hara had been the most frequent contributor of stories to The New Yorker. After the review, he stopped writing for the magazine for over ten years. He only returned in the 1960s when a new editor invited him back.

Many famous writers admired O'Hara's work, including John Updike and Shelby Foote. They liked his skill in writing realistic conversations. They also admired his ability to show how people communicate without words, like through glances or gestures. O'Hara said he learned from Ring Lardner that writing speech exactly as it's spoken creates real characters. He felt his ability to write good dialogue was special, especially since he thought it was missing in many other writers.

According to his biographer Frank MacShane, O'Hara believed he would win the Nobel Prize in Literature after Ernest Hemingway died. He wrote to his daughter, "I really think I will get it." He wanted the prize very much. T.S. Eliot told O'Hara that he had been nominated twice. When John Steinbeck won the prize in 1962, O'Hara sent him a telegram saying, "Congratulations, I can think of only one other author I'd rather see get it."

John O'Hara's Death

John O'Hara died from cardiovascular disease in Princeton, New Jersey. He is buried in the Princeton Cemetery. His wife chose a comment he made about himself for his epitaph: "Better than anyone else, he told the truth about his time. He was a professional. He wrote honestly and well." Brendan Gill found this claim very bold.

After his death, O'Hara's study was rebuilt in 1974 at Pennsylvania State University. His writings and papers are kept there. His childhood home in Pottsville, the John O'Hara House, was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1978.

Books and Stories Made into Films and TV Shows

O'Hara's novel Pal Joey (1940) became a successful Broadway musical. O'Hara wrote the story for the musical, and Rodgers and Hart wrote the songs. In 1957, Pal Joey was made into a musical film. It starred famous actors like Rita Hayworth and Frank Sinatra.

From the Terrace is a 1960 film based on O'Hara's 1958 novel. The movie starred Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward.

Also in 1960, O'Hara's 1935 novel BUtterfield 8 was made into a film with the same name. Elizabeth Taylor won an Academy Award for Best Actress for her role in the movie.

Ten North Frederick is a 1958 film based on O'Hara's 1955 novel. Gary Cooper starred in it. O'Hara thought Cooper's acting was "sensitive, understanding and true."

A Rage to Live is a 1965 film based on O'Hara's 1949 novel. It starred Suzanne Pleshette.

O'Hara's short stories about Gibbsville were used for a 1975 NBC television movie. They also inspired a short-lived 1976 NBC TV series called Gibbsville.

In 1987, O'Hara's 1966 story "Natica Jackson" was adapted for the PBS series Great Performances. It was about a film actress in the 1930s and starred Michelle Pfeiffer.

The TV show Mad Men, which aired from 2007 to 2015, made people interested in O'Hara's work again. This was because the show explored similar themes about American life in the mid-20th century.

Newspaper Columns by O'Hara

In the early 1950s, O'Hara wrote a weekly book column called "Sweet and Sour." He also wrote a column called "Appointment with O'Hara" for Collier's magazine. Biographers said these columns were very opinionated but didn't add much to his important writing.

His later column, "My Turn," for Newsday began in 1964. It lasted for about a year. His first column started with, "Let's get off to a really bad start." In another column, he compared people against smoking to those who supported Prohibition. He also supported the Republican Party candidate Barry Goldwater by linking him to fans of the musician Lawrence Welk. O'Hara wrote, "I think it's time the Lawrence Welk people had their say." He believed these people could be depended on when the country was in trouble. In a different column, he argued that Martin Luther King Jr. should not have received the Nobel Peace Prize.

This syndicated column was not very successful. Fewer newspapers published it over time. It also didn't make him popular with the politically liberal literary community in New York. Several of his columns showed his knowledge of and desire to be associated with Ivy League colleges.

See also

In Spanish: John O'Hara para niños

In Spanish: John O'Hara para niños

| Stephanie Wilson |

| Charles Bolden |

| Ronald McNair |

| Frederick D. Gregory |