Spanish Revolution of 1936 facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Spanish Revolution |

|

|---|---|

| Part of the Spanish Civil War | |

Women training for a militia outside Barcelona, August 1936.

|

|

| Date | July 19, 1936 |

| Location | |

| Goals | Elimination of all institutions of state power; worker control of industrial production; implementation of libertarian socialist economy; elimination of social influence from Catholic Church; international spread of revolution to neighboring regions. |

| Methods | Work place collectivization; political assassination |

| Resulted in | Suppressed after ten-month period. |

The Spanish Revolution was a huge social change that happened during the Spanish Civil War in 1936. For about two to three years, many parts of Spain, especially Catalonia, Aragon, and Andalusia, tried out new ways of organizing society. These ideas were based on anarchist and libertarian socialist principles.

This meant that workers took control of much of the economy of Spain. In places like Catalonia, workers ran about 75% of factories. Farms became "collectives," meaning they were owned and run by groups of people together. Even small businesses like hotels and restaurants were managed by their workers.

The main groups that helped organize these changes were the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT), which was a big workers' union, and the Federación Anarquista Ibérica (FAI), an anarchist group. Another socialist union, the Unión General de Trabajadores (UGT), also helped.

Contents

History of the Spanish Revolution

The Spanish Revolution started when a military uprising began on July 17, 1936. This uprising led to the collapse of the government in many areas. Where the military didn't take control, the old state structures disappeared or stopped working.

At this time, the CNT union had about 1.5 million members, and the UGT union had about 1.4 million. On July 19, the uprising reached Catalonia. Workers there took up weapons, attacked military bases, and built barricades. They eventually defeated the military forces in Catalonia.

The First Phase: Summer of Anarchy (July–September 1936)

The CNT and UGT unions called a general strike from July 19 to 23. This was a response to the military uprising and the government's slow reaction. During this strike, union members took weapons from state depots.

During these first weeks, two main groups formed within the revolutionary movement. The first was a radical group, mostly linked to the FAI and CNT. They saw what was happening as a full-blown revolution. The second group was more moderate, made up of some CNT members. They thought it was better to work with a larger group called the Popular Antifascist Front (FPA). This front included unions and other political parties.

New local and regional groups were formed to manage things, outside of the old government system. Some important ones included:

- The Central Committee of Antifascist Militias of Catalonia

- The Regional Defense Council of Aragon

- The Madrid Defense Council

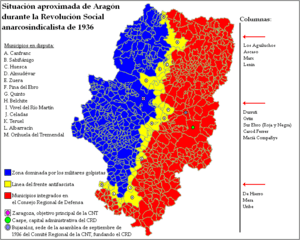

The Spanish Civil War fronts were quickly set up. One key area for the revolution was Aragon. On July 24, 1936, the first volunteer militia, the Durruti Column, left Barcelona for Aragon. This group, led by Buenaventura Durruti, started setting up "libertarian communism" in towns they passed through. Other groups like the Iron Column also formed.

Many anarchists gathered in areas not controlled by the rebel military. The arrival of thousands of anarchist fighters from Catalonia and Valencia, combined with a large rural population in Aragon, helped create the biggest "collectivist" experiment of the revolution.

During this time, workers organized by unions took control of most of the Spanish economy. In anarchist areas like Catalonia, this included 75% of all industries. Factories were run by workers' committees. Farms were collectivized and operated as libertarian communities. Even hotels, hairdressers, and restaurants were managed by their own workers.

The British writer George Orwell, famous for Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four, fought in the war. He was part of a group allied with the CNT. Orwell wrote about his experiences in Homage to Catalonia, showing his admiration for the social revolution.

I had dropped more or less by chance into the only community of any size in Western Europe where political consciousness and disbelief in capitalism were more normal than their opposites. Up here in Aragon one was among tens of thousands of people, mainly though not entirely of working-class origin, all living at the same level and mingling on terms of equality. In theory it was perfect equality, and even in practice it was not far from it. There is a sense in which it would be true to say that one was experiencing a foretaste of Socialism, by which I mean that the prevailing mental atmosphere was that of Socialism. Many of the normal motives of civilized life – snobbishness, money-grubbing, fear of the boss, etc. – had simply ceased to exist. The ordinary class-division of society had disappeared to an extent that is almost unthinkable in the money-tainted air of England; there was no one there except the peasants and ourselves, and no one owned anyone else as his master.

These communities worked on the idea of "From each according to their ability, to each according to their need." In some places, money was completely removed and replaced with vouchers. Goods often cost much less than before. During the revolution, a lot of rural land was taken over: 70% in Catalonia, 70% in Eastern Aragon, and more in other regions. About 54% of this land was collectivized.

The areas where rural communities became most important were Ciudad Real and Jaén. Many of these communities lasted until the end of the war. Anarchist communities actually produced 20% more efficiently than before. Decisions were made by councils of regular citizens, without a lot of complicated rules.

In Aragon, about 450 rural communities were formed, mostly by the CNT. In the Valencia area, 353 communities were set up. One big project there was the Unified Levantine Council for Agricultural Export (CLUEA). In Catalonia, CNT workers took over textile factories, ran trams and buses in Barcelona, and managed fishing and shoe industries. In just a few days, 70% of Catalonia's businesses were owned by workers.

Along with economic changes, there was a cultural and moral revolution. libertarian athenaeums became places for learning and culture. They offered reading classes, health talks, and public libraries. Many new schools were started, following ideas from thinkers like Francesc Ferrer i Guardia. People also challenged old traditions and ideas about society. Anarchist ideas focused on individual freedom and helping each other.

Public order changed too. The usual police and army were replaced by volunteer groups and neighborhood meetings. Many prisons were opened, and some were even torn down.

Carlo Rosselli, an anti-fascist professor, admired the changes. He said that Catalonia built a new social order in three months, thanks to the Anarchists' organizing skills. He believed they were creating a new world.

Despite these changes, the government started trying to regain control. On August 2, it created "Volunteer Battalions," which became the start of the Spanish Republican Army. The government also passed some laws to show it was still in charge, like taking over railways and seizing farms.

Tensions grew between the anarchists and the Communist Party of Spain (PCE). On August 6, PCE members left the Catalan government due to anarchist pressure.

The Second Phase: First Government of Victory (September–November 1936)

In this period, the government mostly just made laws to match the changes already happening. But because of the war, unions started giving control of their fighting groups to the government for the Defense of Madrid. This was managed by a group with all the Popular Front parties, including anarchists. This cooperation led to the formation of Largo Caballero's "first Government of Victory" on September 4.

The government passed laws to support the revolutionaries, like seizing property from those who opposed them. However, the government's main goal was to build up the army and a strong central state. They tried to break up the local war committees.

As the war continued, the early revolutionary spirit faded. Disagreements grew among the Popular Front members, partly because of the Communist Party of Spain (PCE). The PCE was influenced by the Soviet Union, which was sending aid.

The PCE believed that winning the Civil War was the most important thing. They thought the social revolution should wait until after the war. They didn't want to upset the middle classes, who supported the government but might be hurt by the revolution.

Anarchists and the POUM (a left-wing communist party) disagreed. They saw the war and revolution as the same fight. They believed workers had defeated the military because of their revolutionary drive, not to defend an old-style republic. The nationalists represented the very people these revolutionaries were fighting: rich capitalists, landowners, and the Church.

Groups against the government soon found their aid cut off. The government slowly started to undo the changes made in most areas. Revolutionary groups were forced to join or be taken over by the government. Life in most Republican areas slowly went back to how it was before the war.

However, the collective farms in Aragon continued to grow. Thousands of anarchist fighters from Valencia and Catalonia arrived there. In September 1936, the CNT of Aragon decided to create a Regional Defense Council of Aragon. This council was officially recognized by the government on October 6.

Despite this, on September 26, some anarchist groups in Catalonia started working with the government. They joined the Catalan government, and the Central Committee of Antifascist Militias of Catalonia was dissolved. On October 9, the Catalan government outlawed all local committees. These actions were seen by some anarchists as a betrayal of their core beliefs.

The Third Phase: Second Government of Victory (November 1936 – January 1937)

On November 2, the Popular Executive Committee of Valencia agreed to work with the government. This government included CNT members like Juan García Oliver and Federica Montseny. Later that month, the Iron Column briefly took over Valencia to protest supply shortages, leading to clashes.

On November 14, the Durruti Column arrived in Madrid. On November 20, Buenaventura Durruti died in Madrid under unclear circumstances.

On December 17, a Soviet newspaper, Pravda, wrote that the "purge" of anarchists had begun in Catalonia, just like in the Soviet Union. This showed that the Stalinists were starting to get rid of anti-fascists and revolutionary groups that didn't follow Moscow's orders.

By January 1937, the Popular Executive Committee of Valencia was dissolved. During this time, the government took full control of the anarchist militias, forcing them to join the regular Spanish Republican Army under professional officers.

The End of the Revolution (January 1937 – May 1937)

On February 27, 1937, the government banned the FAI's newspaper, starting a period of censorship. The next day, police were forbidden from joining political parties or unions. On March 12, the Catalan government demanded all weapons from non-military groups. Anarchist advisors in the Catalan government resigned on March 27. The "militarization" of the militias into a regular army was completed in March, which many anarchists opposed.

On April 17, government forces took control of customs from CNT workers at the French border. In Barcelona, police disarmed workers in the streets.

In May 1937, fighting increased between supporters and opponents of the revolution. After the Barcelona May Days events, two Communist ministers suggested punishing the CNT and POUM. On May 16, Largo Caballero resigned, and a new government was formed without anarchists.

Fenner Brockway, a British politician who visited Spain, was impressed by the CNT's strength. He noted that the CNT controlled major industries like railways and textiles. He admired their work in creating a new "Workers' Society" and believed they were fighting fascism while building a new world.

Related Subsequent Events

On May 25, 1937, the FAI was excluded from the People's Courts. On June 8, the government outlawed rural communities that hadn't dissolved yet. On June 14, a new Catalan government formed without anarchists. On June 15, the POUM was outlawed and its leaders arrested.

In August 1937, criticizing the Soviet Union was banned. The central government also ordered the dissolution of the Aragon Defense Council, the last major revolutionary group. Republican troops occupied Aragon on August 10, and its president, Joaquín Ascaso, was arrested. Communist forces attacked Aragonese communities and dissolved collective farms, though they were later reorganized.

On September 7, the government allowed private religious worship again. On September 16, political rallies were banned in Barcelona. On September 26, the Asturian Council declared itself independent from the Spanish Republic.

On January 6, 1938, the government banned all local groups from printing their own money. This was an effort to end the last parts of the revolution. Many large landowners returned and demanded their property back. Collectivization was slowly undone, even though it had popular support.

Historian Sam Dolgoff estimated that about eight million people were involved in the Spanish revolution. He said it came closer to creating a free, stateless society than any other revolution.

Gaston Leval also praised the revolution, saying that in Spain, for almost three years, over 60% of the land was farmed collectively by peasants without landlords. Workers managed factories and services without capitalists or state control. He noted that these groups created economic equality, increased production, built schools, and improved public services. They replaced competition with mutual aid and solidarity.

Social Changes During the Revolution

Economic Changes

The most important part of the social revolution was creating a libertarian socialist economy. This meant that industries and farms were run by workers and farmers themselves, in a decentralized way. Andrea Oltmares, a professor from Geneva, said that anarchists showed great organizing skills during the civil war. He admired how they changed Catalonia without needing a dictatorship. Workers managed production and distribution, showing great enthusiasm.

The revolution changed how the economy worked. This included how things were managed, produced, and distributed. This was done by taking over private resources, because anarchists believed that private ownership gave too much power to a few people.

The economic changes that followed the military insurrection were no less dramatic than the political. In those provinces where the revolt had failed the workers of the two trade union federations, the Socialist UGT and the Anarchosyndicalist CNT, took into their hands a vast portion of the economy. Landed properties were seized; some were collectivized, others were distributed among the peasants, and notarial archives as well as registers of property were burnt in countless towns and villages. Railways, tramcars and buses, taxicabs and shipping, electric light and power companies, gasworks and waterworks, engineering and automobile assembly plants, mines and cement works, textile mills and paper factories, electrical and chemical concerns, glass bottle factories and perfumeries, food-processing plants and breweries, as well as a host of other enterprises, were confiscated or controlled by workmen's committees, either term possessing for the owners almost equal significance in practice. Motion-picture theatres and legitimate theatres, newspapers and printing shops, department stores and bars, were likewise sequestered or controlled as were the headquarters of business and professional associations and thousands of dwellings owned by the upper class.

– Burnett Bolloten

Many experiments with worker management happened across Republican Spain. In some towns, changes happened naturally. But in many cases, people copied what was done in Barcelona.

Socialized Industries

After the military uprising, many business owners in Republican areas were killed, jailed, or fled. This left many companies and factories without leaders. Unions then took over these businesses, sometimes entire industries. How this happened depended on things like whether the owner disappeared, how strong the workers' unions were, or if there was foreign money involved. There were three main ways industries were managed:

- Workers' control: This happened when foreign money limited how much workers could change things. Workers had some say but didn't fully own the business.

- Nationalization: The state took over and managed the industry. This was favored by the Communist Party.

- Socialization: Workers themselves managed the industry. This was the anarchist approach. Private ownership was replaced by collective management. A board of directors, elected by workers, ran the company. Profits were shared among workers, the company, and for social purposes like education or health.

At the start of the war, 70% of Spain's industry was in Catalonia. As the center of anarchism, Catalonia saw some of the most radical changes.

Wages and Pay

How workers were paid was a point of disagreement between anarchists and Marxists. Anarchist groups wanted a single family wage, meaning everyone in a family would get the same amount, regardless of their job. Marxist groups wanted wages to be different based on the type of work.

Anarchists believed people would work hard and improve things if they controlled their work. Marxists thought people would work harder if they got paid more.

Examples of Collectivized Industries

Film Industry

The CNT's Entertainment Union was a great example of worker organization. From July 20 to 25, cinemas and theaters in Barcelona were quickly taken over by CNT activists. By July 26, a plan was being made for how to run these places.

From August 1936 to May 1937, revolutionary energy powered all film and theater activities in Barcelona. They set standard wages for all jobs in the film industry. Benefits for sickness, disability, old age, and unemployment were created. This system supported about 6,000 people and ran 114 cinemas, 12 theaters, and 10 music halls. They even started an opera company to make opera available to everyone.

The film industry did very well financially. New cinemas were built, and others were improved. Politically, collectivizing cinema was a new way of thinking about art, against the old capitalist system. They used cameras to film what was happening in the streets, creating a new kind of journalism.

Between 1936 and 1937, over a hundred films were made, supported by CNT production companies. Documentaries were especially important, showing war news. Even after the revolution was suppressed in Barcelona in May 1937, films continued to be made, though at a slower pace.

Woodworking Industry

Between 7,000 and 10,000 people worked in the woodworking industry during the war. After the general strike, woodworkers started to "socialize" their businesses. They took over companies and closed workshops that weren't safe or healthy. They grouped them together into larger, better places.

After a few months, they coordinated their efforts. They achieved an 8-hour day, standard wages, better working conditions, and increased production. All parts of woodworking, from sawmills to carpentry, were socialized.

They created a professional school and libraries. There was even a Socialized Furniture Fair in 1937. They worked with the socialized wood industry in Valencia to avoid competing. While some exchanges were done by trading goods, most still used money.

Agrarian Communities

In Spain, large landowners owned most of the land, which caused problems for peasants. The government's land reforms hadn't fixed this. So, after the military uprising, peasants took land from landowners. They formed self-managed communities based on collective ownership. This was called "collectivization."

These communities were formed in different ways. In areas not taken by nationalists, local governments and peasants started collectivization. They created a system where land, animals, tools, and work were all shared. Regular meetings were held to decide what the community would do and to trade with other communities. Most of these groups formed on land left empty or taken over after the uprising.

The Agrarian Reform Institute counted between 1,500 and 2,500 communities across Spain. These groups were organized regionally, like in Aragon. The UGT's National Federation of Land Workers, with over half a million members, mostly supported these communities.

In Barcelona, urban services like public transport were managed by collective groups. In the countryside of Aragon, Valencia, and Murcia, farming communities acted like communes. They managed production, work, and distribution of goods. In many places, they even got rid of money and private property. Some important Aragonese communities were Alcañiz and Calanda.

Joining or leaving a community was free. If a small owner wanted to farm their own land, they could, as long as they didn't hire anyone.

In Aragon, farming groups were made of 5 to 10 people. Each group was given land to manage. They elected a delegate to represent them at community meetings. A management committee handled daily tasks, like getting materials and trading with other areas. Its members were elected in general meetings.

In many villages, money was replaced by vouchers or local coins. Money was only used to buy things the community couldn't produce itself.

In many communities money for internal use was abolished, because, in the opinion of Anarchists, "money and power are diabolical philtres, which turn a man into a wolf, into a rabid enemy, instead of into a brother." "Here in Fraga [a small town in Aragon], you can throw banknotes into the street," ran an article in a Libertarian paper, "and no one will take any notice. Rockefeller, if you were to come to Fraga with your entire bank account you would not be able to buy a cup of coffee. Money, your God and your servant, has been abolished here, and the people are happy." In those Libertarian communities where money was suppressed, wages were paid in coupons, the scale being determined by the size of the family. Locally produced goods, if abundant, such as bread, wine, and olive oil, were distributed freely, while other articles could be obtained by means of coupons at the communal depot. Surplus goods were exchanged with other Anarchist towns and villages, money being used only for transactions with those communities that had not adopted the new system.

– Burnett Bolloten

The biggest challenges for these communities were the war itself, like shortages of materials and workers. They also had problems with the government, which saw them as rivals. They faced discrimination in funding and were sometimes forced to dissolve.

The Scope of the Revolution

It's hard to say exactly how many people were involved. Estimates range from 1.5 million to over 3 million people. Frank Mintz, a researcher, estimated at least 1,838,000 collectivists in agriculture and industry.

The Revolution in Education

Education also saw big changes. It was no longer just about defending against capitalism but became a key part of building the new revolutionary society.

Primary and Secondary Education

The New Unified School Council (UNSC), created in Catalonia on July 27, 1936, aimed to rebuild education there. It promoted free, co-educational (boys and girls together), and non-religious schooling. However, some rationalist schools stayed outside this system.

In rural areas, communities had to get more involved in education, often because there were no schools before. Many communities also banned child labor.

Vocational and Technical Training

New training programs were created for different jobs. Unions started many of these, as they needed more skilled workers. There were schools for railway workers, opticians, and metalworkers.

In farming, unions created schools like the agricultural university of Moncada.

Non-Formal and Cultural Education

For informal learning, there were libertarian athenaeums. These were popular social centers that offered talks, cultural events, and workshops. They were common where anarchism was strong and even spread to new areas during the war. Some athenaeums created schools, offered health insurance, and promoted other services.

Communities also started libraries, art activities, theater groups, and nurseries.

Problems Faced in Education

Education faced challenges from the war and from long-standing issues.

- Low school attendance: Many children, especially in rural areas, didn't go to school regularly. Communities tried to stop child labor to help this.

- Lack of trained teachers: There weren't enough skilled teachers, especially in rural areas. Many people running the rationalist schools were activists, not professional teachers.

- Lack of coordination: Different rationalist schools often didn't work together.

- Lack of money and materials: The war economy meant there weren't enough resources for schools. Buildings were sometimes repurposed for education.

The Revolution, Civil War, and Militias

The revolution and the Spanish Civil War happened at the same time. New revolutionary groups tried to organize military efforts, but many of these attempts didn't succeed.

The Aragon Front

The first military action was on July 24, 1936, when the Durruti Column left Barcelona for Zaragoza. Other groups also headed towards Huesca and Teruel. This lasted until late September. With the Battle of Madrid coming, some groups gave up their independence and joined the government's army.

The Mallorca Landings

The idea to take back Mallorca, Ibiza, and Formentera from the nationalists came early. Republicans took Ibiza, Formentera, and Cabrera. They landed on Mallorca in September, but the operation ended by September 12, and troops returned to Barcelona. Francoist troops from Mallorca then reoccupied Formentera.

The Defense of Madrid

The last major operation by the confederal militias was in November 1936. Buenaventura Durruti died on November 20, 1936, during the Siege of Madrid. The resistance of the militias and the International Brigades helped Madrid hold out against the rebels. Many anarchists, like Cipriano Mera, fought in this defense.

However, the confederal militias were later forced to become part of the regular Spanish Republican Army in 1937.

Criticisms of the Revolution

Some people criticized the Spanish Revolution, saying that anarchist groups sometimes forced people to join collectives, especially in rural Aragon. Critics like Burnett Bolloten claimed that CNT-FAI reports made it seem like more people joined voluntarily than actually did. He argued that many joined because of pressure or force.

Although CNT-FAI publications cited numerous cases of peasant proprietors and tenant farmers who had adhered voluntarily to the collective system, there can be no doubt that an incomparably larger number doggedly opposed it or accepted it only under extreme duress...The fact is...that many small owners and tenant farmers were forced to join the collective farms before they had an opportunity to make up their minds freely.

Bolloten also pointed out that the war itself created a difficult situation. Even if direct force wasn't used, people might have felt pressured to join. For example, they might not have been allowed to hire workers or sell their crops freely. They might also have been denied benefits given to collective members.

Even if the peasant proprietor and tenant farmer were not compelled to adhere to the collective system, there were several factors that made life difficult for recalcitrants; for not only were they prevented from employing hired labor and disposing freely as their crops, as has already been seen, but they were often denied all benefits enjoyed by members...Moreover, the tenant farmer, who had believed himself freed from the payment of rent by the execution or flight of the landowner or of his steward, was often compelled to continue such payment to the village committee. All these factors combined to exert a pressure almost as powerful as the butt of the rifle, and eventually forced the small owners and tenant farmers in many villages to relinquish their land and other possessions to the collective farms.

Historian Ronald Fraser also said that direct force wasn't always needed. The dangerous war situation, where "fascists" were being shot, was enough pressure. He noted that both "spontaneous" and "forced" collectives existed.

Anarchist supporters argue that the "coercive climate" was part of the war, and anarchists shouldn't be blamed for it. They say that direct force was minimal. Historian Antony Beevor noted that villages often had a mix of collectivists and individualists, showing that people weren't forced at gunpoint.

Historian Graham Kelsey also believes that anarchist collectives were mostly based on voluntary choices. He suggests people joined after capitalism had weakened in the region.

Libertarian communism and agrarian collectivization were not economic terms or social principles enforced upon a hostile population by special teams of urban anarchosyndicalists, but a pattern of existence and a means of rural organization adopted from agricultural experience by rural anarchists and adopted by local committees as the single most sensible alternative to the part-feudal, part-capitalist mode of organization that had just collapsed.

Pro-anarchist analysts also point to decades of organization and activism by the CNT-FAI. They say this long history explains why so many people joined the anarchist collectives, rather than any force being used.

Michael Seidman suggested other issues with worker self-management. He noted that the CNT allowed workers to be fired for "laziness or immorality." He also mentioned that the CNT Justice Minister, García Oliver, started "labor camps" and that even principled anarchists supported "forced labor." However, García Oliver's vision for justice was idealistic. He believed common criminals could improve through libraries and sports in prison. Political prisoners would build fortifications and roads for good wages. He thought it was better to save fascist lives than to execute them, unlike the mass killings in the rebel zone.

Anarchist writers sometimes downplayed the problems faced by workers during the revolution. For example, Gaston Leval admitted that collectives had "strict" work discipline but only mentioned it in a footnote. Other thinkers have used the Spanish experience to argue that to truly move beyond capitalism, workers must completely get rid of wages and capital, not just manage them themselves.

See also

In Spanish: Revolución social española de 1936 para niños

In Spanish: Revolución social española de 1936 para niños

- Anarchism in Spain

- Confederal militias

- Horizontalidad

- Madrid Defense Council

- Popular Executive Committee of Valencia

- Regional Defense Council of Aragon

- Revolutionary Catalonia

- Second Spanish Republic

- Spanish Civil War

- Spanish Coup of July 1936

- Sovereign Council of Asturias and León

Filmography

- Vivir la utopia (Living Utopia), Juan Gamero, 1997, a documentary about Anarchism in Spain and the collectives in the Spanish Revolution

- Land and Freedom. Ken Loach, 1995, a movie based on Orwell's Homage to Catalonia

- Libertarias, Vicente Aranda, 1996, a movie about women fighters on the Aragon front

- Butterfly's Tongue, José Luis Cuerda, 1999, a movie about children in libertarian education

| Calvin Brent |

| Walter T. Bailey |

| Martha Cassell Thompson |

| Alberta Jeannette Cassell |