Albert Parsons facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Albert Parsons

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Albert Richard Parsons

June 20, 1848 |

| Died | November 11, 1887 (aged 39) |

| Occupation | Printer |

| Political party | Republican (before 1875) Socialist Labor (1877-1887) |

| Spouse(s) | Lucy Parsons |

| Conviction(s) | Conspiracy |

| Criminal penalty | Death by hanging |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ |

|

| Years of service | 1861–1865 |

| Unit | |

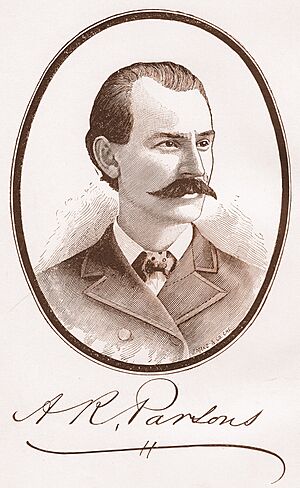

Albert Richard Parsons (born June 20, 1848 – died November 11, 1887) was an important American leader. He worked as a newspaper editor and speaker. He was also a strong supporter of workers' rights. He believed in ideas like socialism and later anarchism.

Contents

Early Life

Albert Parsons was born on June 20, 1848, in Montgomery, Alabama. He was one of ten children. His father owned a shoe and leather factory. Both of Albert's parents died when he was very young.

His oldest brother, William Henry Parsons, raised him. His brother owned a small newspaper in Tyler, Texas. In the mid-1850s, Albert's family moved to the Texas frontier. They later moved to a farm in the Brazos River valley.

In 1859, when he was 11, Albert went to live with a sister in Waco, Texas. He went to school for about a year. Then, he became an apprentice at the Galveston Daily News newspaper. He learned how to be a printer there.

Civil War and Changes in America

When the American Civil War started in 1861, Albert was only 13. He volunteered to fight for the Confederate States of America. He joined a group called the "Lone Star Greys."

After the war, Albert went back to Waco, Texas. He used money from selling corn to pay for school. He studied for six months at Waco University, which is now Baylor.

After college, Albert became a printer again. In 1868, he started his own newspaper, the Waco Spectator. In his paper, Albert supported the new rules after the war. These rules were called Reconstruction. They aimed to protect the rights of former slaves. This was not a popular idea in Texas at the time.

Albert later said that he became a Republican. This made some of his old army friends and neighbors angry. He was even disliked by groups like the Ku Klux Klan. But many former slaves saw him as a friend. His newspaper did not last long because of these strong feelings.

In 1869, Albert worked as a reporter for the Houston Daily Telegraph. He met Lucy Ella Gonzales. They got married in 1872. Lucy Parsons later became a famous activist too.

In 1870, Albert got a job with the U.S. government. He worked for the Internal Revenue Service. He also worked for the Texas State Senate. He held these jobs until 1873.

In 1873, Albert traveled around the Midwestern United States. He decided to move to Chicago. This was a new start for him.

Life in Chicago

Working for Change (1874–1879)

In Chicago, Albert Parsons worked as a typesetter for the Chicago Times.

In 1874, he became interested in workers' rights. This happened after a big fire in Chicago in 1871. A group collected money to help the victims. But many people felt the money was not used fairly. Newspapers called the workers who complained "Communists." This made Albert want to learn more. He realized that there was a big problem with how society was set up.

In 1875, Albert left the Republican Party. He joined a new group called the Social Democratic Party. He became one of their main English-speaking leaders in Chicago.

Albert also joined the Knights of Labor in 1876. This was a very important workers' group. He and his friend George Schilling started the first Knights of Labor group in Chicago.

Albert ran for political office several times in Chicago. He ran for City Alderman, County Clerk, and even for United States Congress. He got many votes but did not win.

In 1877, there was a huge railroad strike. On July 21, Albert spoke to about 30,000 workers in Chicago. He spoke for the Workingmen's Party. The next day, he lost his job at the Times because of his speech.

After losing his job, Albert was called to Chicago City Hall. The Chief of Police and about 30 important citizens were there. They told him he was in danger and should leave town. But Albert stayed in Chicago. The newspapers falsely reported that he had been arrested.

Focus on Workers' Rights (1880–1887)

Around 1880, Albert Parsons stopped trying to win elections. He felt that workers earned too little and worked too many hours. This made it hard for them to vote and have their voices heard. He believed that unfair conditions made it impossible for elections to truly show what people wanted.

Albert then focused on the movement for an 8-hour workday. In 1880, he went to a meeting in Washington, D.C.. This meeting aimed to get labor groups to work together for the 8-hour day.

In 1881, Albert helped start a new group called the International Revolutionary Socialists. Two years later, he joined the International Working People's Association. This group believed in anarchism. He stayed with this group for the rest of his life.

In 1884, Albert started his own weekly newspaper in Chicago called The Alarm. The first issue came out on October 4, 1884. It was a 4-page paper and cost 5 cents. The Alarm was published by the International Working People's Association. It called itself "A Socialistic Weekly."

Albert's paper supported anarchist ideas. He wrote that anarchists believe in peace, but not if it means losing freedom. He felt that laws were made to force people to do things they would not do naturally. He believed that governments tend to make more laws, which can lead to unfair rule.

In early 1886, many workers went on strike. They wanted better pay and shorter hours. Albert Parsons called for "Eight hours' work for ten hours' pay." Some workers even started to get this.

On May 1, 1886, Albert Parsons, his wife Lucy, and their two children led a huge parade. About 80,000 people marched down Michigan Avenue in Chicago. This was the first-ever May Day Parade. It was held to support the eight-hour workday. Over the next few days, 340,000 more workers joined the strike. Albert traveled to Cincinnati to speak to workers there. Everyone felt that they were close to winning their goals.

The Haymarket Affair

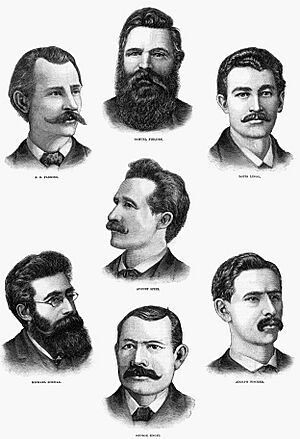

Albert Parsons spoke at a rally in Haymarket Square on May 4, 1886. This rally was held to protest something that happened a few days before. On May 1, a big strike for the eight-hour workday took place. Two days later, police shot at striking workers at the McCormick Reaper Works factory. August Spies and others organized the Haymarket rally to protest this police violence.

Albert Parsons first decided not to speak at the Haymarket rally. He worried it might cause trouble. But he changed his mind and spoke after August Spies. The mayor of Chicago was even there. He saw that the gathering was peaceful. He left when it looked like it would rain. Albert Parsons, his wife Lucy, their children, and others left the rally to go to a nearby hall.

The rally was ending around 10 p.m. Most people were leaving. Then, a large group of police officers arrived. They told the crowd to leave forcefully. At that moment, a bomb was thrown into the square. It killed one policeman and hurt others. Gunfire started, and seven people died. Many others were hurt.

No one knew who threw the bomb. But chaos broke out as police fired into the crowd. Many protesters and police officers died. Most of the police were hurt by their own side's gunfire. Albert Parsons was at the hall when he heard the explosion and gunfire.

Authorities arrested seven men in the days after the Haymarket events. These men were connected to the anarchist movement. Many people thought they promoted radical ideas. This led some to believe they were part of a conspiracy. Albert Parsons avoided arrest at first. He went to Waukesha, Wisconsin. But on June 21, he turned himself in to support his friends.

A lawyer named William Perkins Black led the defense for the arrested men. Witnesses said that none of the eight men threw the bomb. However, all of them were found guilty. Only Oscar Neebe was sentenced to 15 years in prison. The rest were sentenced to death. Samuel Fielden and Michael Schwab asked for their sentences to be changed. Their sentences were changed to life in prison on November 10, 1887. This was done by Governor Richard James Oglesby. These three men were later pardoned by Illinois Governor John Peter Altgeld in 1893. They were set free.

In the week before he was executed, Albert Parsons' newspaper, The Alarm, was published again. Albert wrote a letter from his prison cell. In it, he named Dyer D. Lum as the new editor. He also gave advice to his supporters. He told them not to give up. He asked them to show the unfairness of capitalism and the problems with government.

On November 11, 1887, Albert Parsons, August Spies, Adolph Fischer, and George Engel were executed.

Albert Parsons probably could have had his sentence changed to life in prison. But he refused to ask the governor. He felt that asking would mean admitting he was guilty, which he was not.

Albert Parsons' last words were recorded. He asked, "Will I be allowed to speak, oh men of America? Let me speak, Sheriff Matson! Let the voice of the people be heard! O—" But his words were cut short as the trap-door opened.

Legacy

Albert Parsons was buried in the Waldheim Cemetery in Forest Park, Illinois. A monument called the Haymarket Martyrs' Monument marks the spot.

His wife, Lucy Parsons, was also very important. She was a feminist, a journalist, and a labor leader. She helped start the Industrial Workers of the World.

See also

In Spanish: Albert Richard Parsons para niños

In Spanish: Albert Richard Parsons para niños

Images for kids

| Madam C. J. Walker |

| Janet Emerson Bashen |

| Annie Turnbo Malone |

| Maggie L. Walker |