George Meany facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

George Meany

|

|

|---|---|

Meany c. 1950-56

|

|

| Born |

William George Meany

August 16, 1894 New York City, U.S.

|

| Died | January 10, 1980 (aged 85) Washington, D.C., U.S.

|

| Resting place | Gate of Heaven Cemetery |

| Occupation | Labor leader |

| Spouse(s) | Eugenia McMahon Meany |

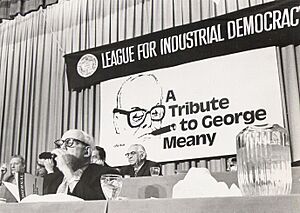

William George Meany (born August 16, 1894 – died January 10, 1980) was an important American labor union leader. He worked in unions for 57 years. He is famous for helping to create the AFL–CIO. This was a very large group of unions. He was also its first president, from 1955 to 1979.

George Meany's father was a union plumber. George followed in his footsteps and became a plumber too. He later became a full-time union official. During World War II, he worked for the American Federation of Labor (AFL). He represented the AFL on the National War Labor Board. He was the president of the AFL from 1952 to 1955.

Meany suggested that the AFL should join with another big union group, the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). He led the talks to make this happen. The two groups merged in 1955. After the merger, he became the first president of the new AFL–CIO. He held this job for 24 years.

People knew Meany as an honest leader. He always fought against corruption in unions. He was also strongly against communism. He was one of the most well-known union leaders in the United States in the mid-1900s.

Contents

Growing Up in New York City

George Meany was born in Harlem, New York City, on August 16, 1894. He was the second of 10 children in his family. His parents, Michael and Anne Meany, were both from Irish families. His family came to the United States in the 1850s. George's father was a plumber and led his local plumber's union. He was also active in the Democratic Party.

When George was five, his family moved to Port Morris in The Bronx. Everyone called him "George." He only found out his real first name was William when he got a work permit as a teenager. George left high school at age 16. He wanted to be a plumber like his dad. He started as a plumber's helper.

He then trained for five years to become a skilled plumber. In 1917, he earned his journeyman's certificate. This meant he was a qualified plumber. He joined Local 463 of the United Association of Plumbers and Steamfitters.

In 1916, his father passed away from heart failure. George's older brother joined the US Army in 1917. This meant George became the main person earning money for his mother and six younger brothers and sisters. For a while, he also played semiprofessional baseball as a catcher to earn more money. In 1919, he married Eugenia McMahon. She worked in clothing factories and was a member of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union. They had three daughters together.

Starting His Union Journey

In 1920, George Meany was chosen to be on the executive board of his plumber's union, Local 463. Two years later, in 1922, he became a full-time business agent for the local. This union had 3,600 members at the time. Meany later said he never had to join a picket line when he was a plumber. This was because employers never tried to replace the workers.

In 1923, he was elected secretary of the New York City Building Trades Council. This group brought together unions for construction workers in the city. In 1927, he won a court order against a company lockout. A lockout is when employers stop workers from coming to work. This was a new idea for unions back then. Many older union leaders did not agree with it.

In 1934, he became president of the New York State Federation of Labor. This was a group of trade unions across the state. In his first year, he worked hard in Albany, the state capital. He helped pass 72 new laws that supported workers. He also built a strong relationship with Governor Herbert H. Lehman.

Meany became known for being honest and hardworking. He was good at speaking to lawmakers and the press. In 1936, he helped start the American Labor Party. This was a political party in New York that supported unions. He worked with David Dubinsky and Sidney Hillman to create it. The party helped get support from union members for President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Mayor Fiorello La Guardia to be re-elected.

Leading Unions Nationally

Three years later, in 1939, Meany moved to Washington, D.C. He became the national secretary-treasurer of the American Federation of Labor (AFL). He worked under AFL president William Green.

During World War II, Meany was one of the AFL's representatives on the National War Labor Board. This board helped settle labor disputes during the war. During this time, he became close with other union leaders who were against communism. These included David Dubinsky and Matthew Woll. In October 1945, he led the AFL to boycott a meeting to create the World Federation of Trade Unions. This group included unions from the USSR. Meany and others saw it as a group controlled by communists.

After the war, there were many labor strikes in 1945 and 1946. Many of these were organized by CIO unions. These strikes led to a new law in 1947 called the Taft Hartley Act. Many people thought this law was against unions. One part of the law said that union officials had to sign a paper saying they were not communists. This greatly affected CIO unions. Meany said he would gladly sign such a paper. He said he had always kept away from communists. Most U.S. union leaders who were not communists signed the paper. The Supreme Court later said this part of the law was legal.

Joining Forces: AFL and CIO Merge

In 1951, AFL President William Green's health began to fail. George Meany slowly took over the daily running of the AFL. When Green passed away in 1952, Meany became the president of the American Federation of Labor.

Meany quickly took charge of the AFL. He then suggested that the AFL should merge with the CIO. It took some time for Walter Reuther to gain full control of the CIO. But once he did, he was ready to work with Meany on the merger.

It took Meany three years to make the merger happen. He had to overcome many people who were against it. John L. Lewis of the United Mine Workers union called the merger a "rope of sand." His union refused to join the new AFL–CIO. Jimmy Hoffa, a leader in the Teamsters Union, also complained. However, the Teamsters did join at first. Mike Quill, president of the Transport Workers Union of America, also fought the merger. He said it meant giving in to "racism, racketeering and raiding" by the AFL.

Meany wanted to make the merger happen quickly. He decided that all AFL and CIO unions would be accepted into the new organization as they were. Any disagreements or overlaps would be sorted out later. Meany also relied on a small group of trusted advisors. They helped write the agreements needed for the merger.

Meany's hard work paid off in December 1955. The two groups held a joint meeting in New York City. They officially merged to create the AFL–CIO. Meany was elected as its first president. Time magazine called this Meany's "greatest achievement." The new group had 15 million members. Only about two million U.S. workers were in unions that stayed outside the AFL–CIO.

Fighting Union Corruption

In 1953, the International Longshoremen's Association was accused of illegal activities. It was kicked out of the AFL. This was an early example of Meany's efforts against corruption in unions. After the union made changes, it was allowed back into the merged AFL–CIO in 1959.

Meany also fought corruption in the United Textile Workers of America starting in 1952. In 1957, he reported that the president of that union had stolen over $250,000. Meany also appointed an independent person to watch over the union's reforms.

Concerns about corruption in the International Brotherhood of Teamsters union grew. This union was led by Dave Beck. Meany began a campaign to reform the Teamsters in 1956. In 1957, Beck was called to testify before a special committee in the U.S. Senate. This committee was looking into improper activities in labor unions.

Televised hearings in 1957 showed bad behavior by both Beck and Jimmy Hoffa, who was fighting Beck for control of the Teamsters. Both Hoffa and Beck were charged with crimes. Hoffa eventually won control of the Teamsters. In response, the AFL–CIO made a new rule. It said that any union official who used the Fifth Amendment (to avoid self-incrimination) during a corruption investigation could not stay in a leadership role. Meany told the Teamsters they could stay in the AFL–CIO if Hoffa stepped down as president. Hoffa refused. So, the Teamsters were kicked out of the AFL–CIO on December 6, 1957. Meany supported the AFL–CIO's new code of ethics after this scandal.

Meany also organized campaigns against corruption in other unions. These included the International Jewelry Workers Union and the Laundry Workers International Union. He demanded that corrupt union officials be removed. He also pushed for unions to reorganize themselves. When some unions refused, he had them expelled from the AFL and later from the AFL–CIO. He even started new, rival unions. He created an AFL–CIO Committee on Ethical Practices. This committee investigated bad behavior. He insisted that unions being investigated cooperate with its inquiries. A professor named John Hutchinson said that "few American union leaders have such a public record of repeated and explicit opposition to corruption."

Views on the Vietnam War

George Meany always supported President Lyndon B. Johnson's policies during the Vietnam War. In 1966, Meany insisted that AFL–CIO unions give "unqualified support" to Johnson's war policy. Some AFL–CIO critics who opposed Meany and the war at that time included Ralph Helstein and George Burdon.

Charles Cogen, president of the American Federation of Teachers, disagreed with Meany in 1967. This was when the AFL–CIO convention voted to support the war in Vietnam. Meany gave a speech at the convention. He said that the AFL–CIO was not "hawk nor dove nor chicken." He meant they were not extreme for or against the war. Instead, they were supporting "brother trade unionists" who were fighting against communism.

Meany was against communism and identified with working-class people. He did not like the New Left movement. This group often criticized labor activists for being too traditional and anti-communist. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, some in the New Left supported communism. After the violence between antiwar protesters and police at the 1968 Democratic National Convention, Meany supported the police. He called the protesters a "dirtynecked and dirty-mouthed group of kooks."

Meany opposed U.S. Senator George McGovern's run for president in 1972. McGovern was against the war. Meany did not support McGovern, even though McGovern usually voted in favor of labor. However, Meany also refused to support the current president, Richard Nixon. In September 1972, Meany appeared on a TV show called Face the Nation. He criticized McGovern for saying the U.S. should respect other people's right to choose communism. Meany said that no country had ever freely voted for communism. He accused McGovern of being "an apologist for the Communist world."

After Nixon won the election by a lot, Meany said that Americans had "overwhelmingly repudiated neo-isolationism" in foreign policy. This meant voters did not want the U.S. to stay out of world affairs. Meany also said that American voters had split their votes. They supported Democrats in Congress but voted for Nixon for president.

Meany continued to support the war effort until the very end. This was just before Saigon was captured by the North Vietnamese in April 1975. He asked President Gerald Ford to send a US Navy "flotilla." This was to help hundreds of thousands of "friends of the United States" escape. He wanted them to get out before a communist government took over.

He also asked for as many Vietnamese refugees as possible to be allowed into the United States. Meany blamed Congress for "washing its hands" of the war. He said they weakened South Vietnam's military. This hurt its "will to fight." In particular, Meany accused Congress of not giving enough money for U.S. troops to leave in an orderly way.

Differences with Walter Reuther

Even though they worked together for the AFL–CIO merger, Meany and Reuther often disagreed. In 1963, they had different opinions about the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. This was a very important event in the civil rights movement in the United States. Meany was against the AFL–CIO officially supporting the march. At an AFL–CIO meeting on August 12, Reuther suggested a strong endorsement of the march. Only A. Philip Randolph, a leader of the march, supported Reuther's idea. The AFL–CIO did support a civil rights law. It also allowed individual unions to support the march. When Meany heard Randolph's speech after the march, he was clearly touched. After that, he supported creating the A. Philip Randolph Institute. This group aimed to make labor unions stronger among African Americans. It also worked to improve ties with the African American community. Randolph said he was sure that Meany was morally against racism.

At the 1967 AFL–CIO convention, Reuther demanded that Meany make the AFL–CIO more democratic.

After years of disagreements with Meany, Reuther left the AFL–CIO executive council in February 1967. In 1968, Reuther's UAW union left the AFL–CIO. The UAW did not rejoin the AFL–CIO until 1981. This was long after Reuther died in a plane crash in 1970.

Political Goals and Later Years

In 1965, during President Johnson's Great Society reforms, Meany and the AFL–CIO supported a plan. This plan called for things like government hearings on company prices. It also wanted a national planning agency. A socialist writer named Michael Harrington said that the AFL–CIO's plan was similar to older socialist ideas. This was different from the ideas of Samuel Gompers, who founded the AFL. Gompers had been against socialism for many years. The 1965 plan was part of the AFL–CIO's support for "industrial democracy." This means giving workers more say in how businesses are run. Even though Meany supported some policies that sounded "socialist," he also said he believed in the "free market system." He said that people who own homes and property tend to become more traditional in their views.

As AFL–CIO president, Meany supported raising the minimum wage. He also wanted more government spending on public projects. He worked to protect the rights of unions to organize. He also supported universal health care for everyone. While he was president, the AFL–CIO worked hard to achieve its goals. He believed in supporting political parties that helped unions and opposing those that did not.

By the mid-1970s, Meany was over 80 years old. More and more people thought he should retire. They wanted a younger person to lead the AFL–CIO. In his final years, Meany enjoyed photography and painting as hobbies.

In June 1975, Meany, as president of the AFL–CIO, hosted Alexander Solzhenitsyn. Solzhenitsyn was a famous Russian writer visiting the USA. Meany held a dinner in his honor. Solzhenitsyn gave one of his most famous speeches there. Meany introduced Solzhenitsyn with a powerful speech.

Meany's wife, Eugenia, passed away in March 1979. They had been married for 59 years. He became very sad after losing her. A few months before he died, he hurt his knee while golfing. He had to use a wheelchair. In November 1979, he retired from the AFL–CIO. He had worked in organized labor for 57 years. Lane Kirkland took over as AFL–CIO president. He served for the next 16 years.

George Meany died on January 10, 1980, at George Washington University Hospital. He passed away from a cardiac arrest (heart attack). The AFL–CIO had 14 million members when he died. President Jimmy Carter called him "an American institution" and "a patriot." He was buried at Gate of Heaven Cemetery in Silver Spring, Maryland.

Awards and Legacy

President John F. Kennedy created the Presidential Medal of Freedom on February 22, 1963. But he died before he could give it out. Two weeks after Kennedy's death, President Lyndon Johnson gave the medal to Meany and thirty other people. This was on December 6, 1963. Johnson said the award was for Meany's service to unions and for helping freedom around the world.

On November 6, 1974, Meany dedicated the George Meany Center for Labor Studies. This center was founded in 1969. It was later renamed the National Labor College in 1997. From 1993 to 2013, the college kept the George Meany Memorial Archives. In 2013, these historical documents were moved to the University of Maryland libraries. This university is now the official place for these records. The collection includes records from the start of the AFL in 1881. It has almost complete records from when the AFL–CIO was founded in 1955. There are about 40 million documents. These include records from different AFL–CIO departments and international unions. There are also personal papers of union leaders. The collection also has many photos of union activities from the 1940s until now. Plus, there are graphic images, over 10,000 audio tapes, hundreds of movies and videos, and more than 2,000 historical items. All of these are available for public research.

The George Meany Award was created by the Boy Scouts of America in 1974.

Books written about Meany include Meany: The Unchallenged Strong Man of American Labor (1972) and George Meany and His Times: A Biography (1981). His entry in the biographical encyclopedia American National Biography was published in 2000. It was written by historian David Brody.

Meany was known for smoking cigars. Pictures of him often appeared in newspapers and magazines with a cigar.

In 1994, on the 100th anniversary of his birth, George Meany was featured on a United States commemorative postage stamp.

See also

- American Federation of Labor

- Argo features a scene about his death

- "Bart of Darkness", with a fictionalized cameo