Alpha Suffrage Club facts for kids

The Alpha Suffrage Club was a very important group for Black women in Chicago. It was the first club of its kind there and one of the most important in Illinois. Ida B. Wells started it on January 30, 1913. She had help from her white friends, Belle Squire and Virginia Brooks.

The club wanted to give a voice to African American women. These women were often left out of big groups like the National American Women Suffrage Association (NAWSA). The Alpha Suffrage Club wanted to teach Black women about their right to vote. They also helped them choose leaders who would support African Americans in Chicago.

Women in Chicago got the right to vote in 1910. The club then worked to make sure Black people could vote. They also wanted to help Black leaders get elected. Ida B. Wells said that women could use their votes to help themselves and their community. She also said the club wanted to help elect a good Black leader for the city council. Wells also encouraged women to make sure their husbands voted too.

At the club's first birthday, Bettiola Heloise Fortson read her poem "Brothers." She was the club's vice-president. The poem was about two men who were unfairly killed while trying to save their sister.

In October 2021, a special sign was put up for the Alpha Suffrage Club. It is part of the National Votes for Women Trail. The sign is at the club's old spot in Chicago.

Contents

Why the Club Was Needed

In 1913, when the club started, there were many unfair rules called Jim Crow laws. These laws treated Black people differently. Black women often faced unfair treatment and had fewer chances for education or good jobs. They were expected to stay home or work on farms. They also had little protection from unfair actions. This unfairness made Ida B. Wells-Barnett want to start the club.

Wells said that many Black women did not focus on voting at first. This was because men and churches in their communities did not always support it. Once women could vote, many did not know how. The Alpha Suffrage Club helped by going door-to-door. They also helped Black women sign up to vote.

African American women had a tough choice. Black men who could already vote wanted them to focus on race issues. White women who wanted to vote wanted them to focus only on women's voting rights. But Black women knew their lives were affected by both their race and their gender.

Working with White Suffragists

Early on, many people who wanted women to vote also wanted to end slavery. They worked together after the Civil War. Frederick Douglass, a famous leader, even used his newspaper to tell people about a meeting for women's voting rights in 1848. A group called the American Equal Rights Association started in 1866. It wanted voting rights for everyone.

But things changed after the 14th and 15th Amendments. These amendments gave Black men the right to vote. Then, the groups split. Racism became a problem in some women's voting rights groups.

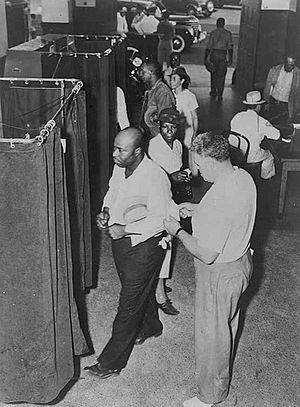

As time went on, getting the right to vote became the main goal. Some groups used the issue of Black voting rights to gain support. Women in the South especially did not want Black women to vote. Ida B. Wells was told she could only march in a separate section for Black women at a big parade. But Wells still joined the white women marching that day.

About a year later, Wells started the Alpha Suffrage Club. This club supported voting rights for all women, no matter their race or social class. Other popular women's groups did not always do this. The movement became divided. Some supported voting rights for all women, and others only for white women. Ida B. Wells believed that not giving everyone the right to vote would hurt the whole cause. So, the Alpha Suffrage Club supported voting rights for all people.

The 19th Amendment was passed in 1920. It gave all women the right to vote, no matter their race or background. So, even with the racism early on, the final law was fair.

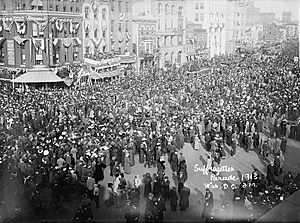

The 1913 Women's Voting Rights Parade

The Woman Suffrage Procession happened in Washington, D.C., on March 3, 1913. This was the day before Woodrow Wilson became president. The parade wanted to show support for all women getting the right to vote. One of Ida B. Wells' first actions as the club's president was to go to Washington. She marched in the parade with 65 Black women from Illinois. The way they were treated showed the unfairness Black women faced in the voting rights movement.

The National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) organized the parade. They worried about upsetting white women from the South. So, they told Wells to march at the very end, in a separate section for African American women. Wells refused. Grace Wilbur Trout, who led the Illinois group, warned Wells that her actions could get the whole Illinois group kicked out. But Wells said she would not move to the back. She said, "I shall not march at all unless I can march under the Illinois banner." Wells wanted to show everyone that Illinois was fair enough to let women of all races march together.

Only Belle Squire and Virginia Brooks, two white friends, supported Wells. They offered to march with her at the back. But Wells decided to wait in the crowd. When the Chicago group marched by, she stepped out and joined them. A picture of this was in the Chicago Daily Tribune newspaper. A reporter saw Wells join the parade. However, only Wells-Barnett marched with the Illinois group. The other Black women from the Alpha Suffrage Club marched at the back with other Black groups. The club paid for Wells' trip so she could march.

What the Club Believed In

The Alpha Suffrage Club had many strong beliefs that other groups did not. The club believed that all women, no matter their race, should get the right to vote, just like men. Other groups wanted women to vote, but many did not support voting rights for women of color.

The club believed that to truly use their voting rights, people needed to be involved in politics. Their group in Chicago worked on laws about voting, fairness, and other civil rights. They also helped their community to make Black people stronger in Chicago. They were early supporters of fairness for Black people in many ways. Ida B. Wells taught that men were not always using their votes well. Now that both men and women could vote, their goal was to use the vote as much as possible. They wanted fairness and power for women of color.

Besides voting rights for all, the club also fought for racial fairness in other areas. They questioned why brave soldiers were judged by their race instead of their actions.

Illinois Equal Suffrage Act

Wells-Barnett started the Alpha Suffrage Club because she saw white women working hard to pass a law in Illinois. This law would give women limited voting rights in the state. Soon after the Washington parade, Wells-Barnett led hundreds of Black women to the Capitol building in Springfield. They wanted to support the Illinois Equal Suffrage Act. They also spoke out against unfair Jim Crow bills.

The Illinois Equal Suffrage Act became law on June 26, 1913. This made Illinois the first state in many years to give women voting rights. This big step for voting rights in Illinois helped the national effort for a voting rights amendment.

A car parade in Chicago celebrated the new law. On July 1, Wells-Barnett was a parade leader. She rode with her daughter down Michigan Avenue. But only the Chicago Defender newspaper mentioned her important role. Other Chicago papers did not.

The Illinois Equal Suffrage Act happened because many voting rights groups worked together. Social clubs at that time were often separated by race. Historians have noted that women's clubs in Chicago created the most and largest women-only voting rights clubs in the country. Because Black women were often left out, Wells and Squire started the Alpha Suffrage Club. It was in a part of the city with many African Americans. The club even held a meeting at a prison to get prisoners interested in voting rights. This also gave club members practice in activism. By 1916, the club had almost 200 members. Famous women like Mary E. Jackson, Viola Hill, Vera Wesley Green, and Sadie L. Adams were members. Jane Addams often spoke at the club.

Because of this new law, women in Illinois could vote for president, mayor, city council members, and most other local leaders. But they could not vote for members of Congress or the Governor. To vote for those, the state constitution needed to be changed.

Helping Elect Oscar De Priest

The Alpha Suffrage Club played a big part in Chicago politics. This was especially true in the 1915 election for city council in the 2nd Ward. The club created a system to go block by block. They helped Black women in the area sign up to vote. In 1914, the club helped 7,290 women register to vote. This was in a ward where 16,237 men were registered.

In an early election, the club supported William R. Cowen, a Black candidate. He was not supported by the main Republican Party. Even with the women's hard work, he lost by only 352 votes. But the press quickly saw the club's power. The Chicago Defender said that "the women’s vote was a revelation to everyone." The Republican Party also noticed the club. They sent people to the club's meeting the day after the election. They told the women to keep working. They also promised to support a Black candidate next year.

After that election, the club members kept working. They focused on areas with many African Americans. They also held weekly meetings to talk about being good citizens. They showed women how to use voting machines. They also trained women to work at voting places. They gave out lists of voting locations all over the city.

The women's efforts faced criticism. Men made fun of them. They told them they should be home with their babies. Others said they were trying to take men's places. Local newspapers worried about women going door-to-door. They were concerned about what women might see.

After the club's success in 1914, the Republican Party chose Oscar De Priest as their candidate. He ran for city council in the 2nd Ward. He ran against two white candidates and won. He was the first Black city council member in Chicago. He served from 1915 to 1917. The club's work was clearly important. One-third of the votes he received were from women. De Priest and the club knew each other well. He often went to their meetings during the elections. After he won, De Priest thanked the women in the 2nd Ward for their help. News of the club's success spread. A Black newspaper in Indianapolis proudly reported that a Black man was elected to the city council. They said it was "in no small part" due to the 1,093 votes from Black women.

De Priest served only one term because of accusations. But his career continued. He later became the first African American elected to the U.S. Congress after the Reconstruction era. The Alpha Suffrage Club's influence in the Second Ward stayed strong. Another Black city council member, Louis B. Anderson, took De Priest's place. This showed a lasting change in Chicago's Second Ward.

Alpha Suffrage Record

The Alpha Suffrage Club published a newsletter called the Alpha Suffrage Record. It announced the club's start and described its activities. It also helped the club reach more African Americans in the city. It focused on the people in the 2nd Ward. This newsletter gave the club women a public voice in politics.

How the Alpha Suffrage Club Made a Difference

The women's voting rights parade of 1913 made the whole movement stronger. The Alpha Suffrage Club's protest against being forced to march at the back showed that racism was a problem even within a united movement. NAWSA wanted white women to get the right to vote first. But the Alpha Suffrage Club and other groups pushed back. Because of their efforts, the 19th Amendment gave voting rights to all women, no matter their race.

The club's power was clear after the 1914 elections. Republican leaders went to a club meeting. They promised to choose a Black candidate if the women supported them. The club played a key role in electing Oscar DePriest. He then supported women's voting rights. This helped the club's causes in the years that followed. It helped them use their social reforms to gain political power.

Locally, the Alpha Suffrage Club started a system to go door-to-door in neighborhoods. They held weekly meetings to teach people about their rights as citizens. They also helped women sign up to vote by going block by block. The club's protests and actions also helped push the U.S. Congress to approve the 19th Amendment on June 10, 1919. It became law on August 18, 1920.

Important Members

- Ida B. Wells-Barnett, co-founder and president

- Belle Squire, co-founder who supported Wells-Barnett during the 1913 parade

- Virginia Brooks, co-founder who supported Wells-Barnett during the 1913 parade

- Mary E. Jackson, the first vice president of the club

- Sadie L. Williams, who handled letters

- Viola Hill, second vice president

- Vera Wesley Green, who kept records

- Laura Beasley, treasurer

- Kizziah J. Bills (also known as Mrs. K. J. Bills), editor

- E.D. Wyatt

- W.N. Mills

- J.E. Hughes

- Bettiola Heloise Fortson, vice president

See also

In Spanish: Club Sufragista Alpha para niños

In Spanish: Club Sufragista Alpha para niños

- African-American Women's Voting Rights Movement

- Timeline of women's suffrage in the United States

- Woman's club movement

- Women's suffrage in the United States

| Bessie Coleman |

| Spann Watson |

| Jill E. Brown |

| Sherman W. White |