Grace Wilbur Trout facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Grace Belden Wilbur Trout

|

|

|---|---|

Suffragist

|

|

| Born | March 18, 1864 |

| Died | October 21, 1955 (aged 91) |

| Resting place | Evergreen Cemetery Jacksonville, Florida |

| Occupation | Women's rights activist |

| Spouse(s) | George William Trout |

| Children | Thomas Wilbur Trout Philip Wilbur Trout Ralph Belden Trout John Vernon Trout |

Grace Belden Wilbur Trout (born March 18, 1864 – died October 21, 1955) was an important American leader for women's voting rights. She was a suffragist, which means she worked to get women the right to vote. Grace Trout led two major groups in Illinois that fought for suffrage: the Chicago Political Equality League and the Illinois Equal Suffrage Association (IESA).

She played a key role in getting a law passed in Illinois that allowed women to vote in some local and national elections. This law was a big step forward for women's rights. Even though she was new to working with lawmakers, she created a smart plan to convince them. She also organized public events and got good news coverage to help people support women's voting rights.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Grace Trout was born on March 18, 1864, in Maquoketa, Iowa. She went to public schools in Iowa. She also had private lessons to learn how to speak well in public.

In 1886, she married George William Trout. They had four sons together. Sadly, one of their sons passed away in 1912 when he was 21 years old. The family moved to Chicago in 1884. Later, they moved to Oak Park, a suburb near Chicago. Grace Trout also wrote a novel called A Mormon Wife, which was published in 1896.

Leading the Fight for Women's Vote

Grace Trout was known as a strong leader in the women's suffrage movement. People described her as charming, hardworking, and talented. She was a brave speaker and good at raising money for the cause.

Becoming a Leader

Grace Trout was involved in many women's clubs in her community. Her work for women's voting rights really took off in 1910. That year, she became the president of the Chicago Political Equality League. This group was started in 1894 by the Chicago Women's Club.

During her two years as president, she helped the league grow. More people joined, and they held meetings more often. The group also printed pamphlets and collected signatures on petitions. These were used to ask the state lawmakers to give women the right to vote. Grace Trout and other activists, like Catharine Waugh McCulloch, traveled around Illinois. They gave speeches and organized events, such as the Suffrage Automobile Tour, to spread their message.

In 1912, Grace Trout was chosen to be the president of the Illinois Equal Suffrage Association (IESA). This group was connected to the National Woman Suffrage Association. She led the IESA almost every year until 1920. As president, she changed how the group worked. She wanted to create more local groups and talk directly to individual lawmakers. Her new, more careful approach helped women's suffrage make big progress.

A Surprising Victory

For many years, bills to give women the right to vote had been introduced in the Illinois state legislature. But they often failed. Many people didn't expect a new bill to pass, especially with Grace Trout and her legislative chair, Elizabeth Knox Booth, being somewhat new to this kind of work.

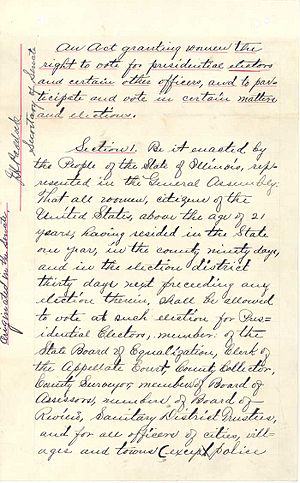

However, these new leaders worked with supporters in the legislature. They introduced a bill in 1913 that would allow women to vote for president and for local offices. This bill did not include voting for state or national representatives, or for governor. Grace Trout organized public support and ran a very smart lobbying effort. Lobbying means trying to convince lawmakers to vote a certain way.

The bill passed on June 11, 1913. Then, on June 26, 1913, the governor of Illinois, Edward Dunne, signed the Illinois Suffrage Act. This law gave women in Illinois limited voting rights.

Building Public Support

Grace Trout had a modern plan to get people to support women's suffrage.

- She made sure a local suffrage club was started in every area. This way, members could talk to their local lawmakers.

- She planned public events across the state, like car tours and speaking events. These events showed how much local support there was.

- She worked with newspapers in Springfield and Chicago. She wanted them to print good stories about the IESA's work.

- She would meet with newspaper managers. She explained the challenges they faced and asked them to write helpful articles.

- She even had newspapers with pro-suffrage articles placed on lawmakers' desks. This made it seem like support for suffrage was everywhere.

Working with Lawmakers

Under Grace Trout, the IESA's work in the state capital, Springfield, became quieter and more subtle. At first, it was just Trout and Elizabeth Booth. Later, two more women joined them: Antoinette Leland Funk and Ruth Hanna McCormick. Reporters called these four women "the Big Four."

In the past, suffrage leaders like Catharine McCulloch had used big, public actions. These included bringing many women by train to Springfield and holding special hearings. Her style was more direct and "militant."

But Trout's team worked differently. They kept their lobbying efforts mostly private. This was to avoid making opponents, especially the powerful alcohol industry, too upset. It also left room to convince lawmakers who were against suffrage.

Grace Trout was very good at talking to people. She was diplomatic and used "extreme tact." She could even be "ingratiating," meaning she was good at winning people over. Historians said her methods might have seemed simple, but she was excellent at working with people. One lawmaker described the "Big Four's" tactics as "noiseless."

Elizabeth Booth used a special card system. She had a picture of every lawmaker and wrote down things about them. This included how they voted, if they might support suffrage, and even how their wives felt about it. Trout and Booth used this system to understand lawmakers and build support from different political parties.

To influence the Speaker of the House, William B. McKinley, members of the Chicago Political Equality League organized a "telephone brigade." They called McKinley every fifteen minutes to show him how much support there was for suffrage. This led to McKinley bringing the bill up for a vote, which had not happened before. On the day of the vote, Trout hired a taxi to bring any missing supporters to the state capitol. She also stood at the door to make sure supporters didn't leave and that opponents didn't illegally enter the voting area.

Other Reasons for Success

Several other things helped the suffrage bill pass.

- More people, especially educated, middle-class women, started to accept suffrage. Events like the car tours helped make suffrage seem "more respectable."

- The movement grew to include women from all social classes, not just the middle class.

- Wealthier women held many leadership roles later in the suffrage movement. This led to a more careful approach. Trout's bill for partial suffrage was less demanding than the full voting rights some others wanted.

- The actions of suffragettes in England also helped. They were sometimes violent, which made the American suffragists seem calmer in comparison.

- Trout and her team were willing to talk and negotiate, even with those who opposed them.

- Finally, events in Washington, D.C., also increased support. A large Woman Suffrage Procession was held on March 3, 1913. Women marching in this parade were treated very badly by bystanders. This unfair treatment made many people feel sympathy for the suffragists and support their cause.

During this march, a challenge arose regarding African-American suffragist Ida B. Wells. Some leaders wanted black suffragists to march in a separate group to avoid upsetting Southern marchers. Grace Trout was personally against this separation, but she worried about losing support for the event. However, Ida B. Wells bravely ignored these requests and marched proudly alongside her Illinois group.

Impact of the Illinois Law

The Illinois Suffrage Act was a huge moment for women's voting rights. It allowed women in Illinois to vote for local officials and for presidential electors. This increased the number of presidential electors women could vote for from 37 to 54. Even though it was not full voting rights, it had a big impact.

This success in Illinois helped women in New York gain suffrage. That victory was a very important step toward women getting full voting rights across the country with the Nineteenth Amendment. A national suffrage leader, Carrie Chapman Catt, said that the Illinois victory was "astounding" and that "suffrage sentiment doubled over night."

Grace Trout's Later Suffrage Work

After the Illinois Law passed, people who opposed it tried many times to say it was against the law. As the leader of the IESA, Grace Trout fought against these efforts. Thanks in part to the IESA's work, attempts to cancel or weaken the law failed.

Trout also encouraged women to vote and use their new rights. She was one of the leaders of a "rainy day suffrage parade" in 1916. In this parade, protesters successfully convinced the Republican Party to include support for suffrage in their political plan.

Trout also led the IESA's efforts to create a new state constitution. She believed this would be the fastest way to get full voting rights for women. She also helped in the national fight for a federal suffrage amendment. She gave many speeches and even met with President Woodrow Wilson. In 1920, Grace Trout ended her suffrage career when the IESA changed into the League of Women Voters of Illinois.

Personal Life

Grace Trout wrote that she first agreed to be president of the IESA because her 21-year-old son encouraged her. He had seen women in California fight for suffrage. Sadly, he passed away shortly after she accepted her first IESA presidency.

Sometimes, more radical suffragists criticized Grace Trout for news stories that focused on her fancy clothes and large hats. But she was widely admired as a speaker and a leader. People noted that she was very successful at giving speeches without notes. She studied her topics deeply, prepared carefully, and her speeches were full of wit and humor.

In 1921, Grace Trout moved to Jacksonville, Florida. There, she became the first president of the Planning and Advisory Board and president of the Jacksonville Garden Club. She lived at a large home called Marabanong. Grace Trout passed away on October 21, 1955, in Jacksonville. She was buried in Evergreen Cemetery.

Published Works

- "Why Illinois Needs a New Constitution." Springfield, Ill. 1918.

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |