Mary McLeod Bethune facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Mary McLeod Bethune

|

|

|---|---|

Bethune photographed by Carl Van Vechten on April 6, 1949

|

|

| Born |

Mary Jane McLeod

July 10, 1875 |

| Died | May 18, 1955 (aged 79) Daytona Beach, Florida, U.S.

|

| Occupation |

|

| Spouse(s) |

Albertus Bethune

(m. 1898; sep 1907) |

| Children | 1 |

Mary Jane McLeod Bethune (née McLeod; July 10, 1875 – May 18, 1955) was an amazing American leader. She was an educator, someone who helped others (a philanthropist and humanitarian), and a civil rights activist. This means she worked hard to make sure all people, especially African Americans, had equal rights and opportunities.

Mary McLeod Bethune started the National Council of Negro Women in 1935. This group helped African American women and their communities. She also advised President Franklin D. Roosevelt and helped create the "Black Cabinet." This was a group of African American leaders who advised the president.

She is also famous for starting a private school for African-American students in Daytona Beach, Florida. This school later grew into Bethune-Cookman University. Mary McLeod Bethune was the only African American woman officially part of the U.S. team that created the United Nations charter. This important document set up the United Nations, an organization that works for world peace.

Because of her lifelong work, she was called "acknowledged First Lady of Negro America" by Ebony magazine. She was also known as "The First Lady of The Struggle" because she was so dedicated to improving lives for African Americans.

Mary McLeod Bethune was born in Mayesville, South Carolina. Her parents had been slaves. She started working in fields with her family when she was just five years old. She really wanted to get an education. With help from people who supported her, Bethune went to college. She hoped to become a missionary in Africa.

Instead, she started a school for African American girls in Daytona Beach, Florida. This school later joined with a school for boys and became the Bethune-Cookman School. She made sure the school had high standards. She also promoted the school to tourists and donors to show what educated African Americans could achieve. She was the president of the college for many years, from 1923 to 1942, and again from 1946 to 1947. She was one of the few women in the world to be a college president at that time!

Bethune was also very active in women's clubs. These groups helped their communities. She became a national leader in these clubs. She wrote many articles for different newspapers and journals. After helping Franklin D. Roosevelt's presidential campaign in 1932, she became part of his "Black Cabinet." She told him about the concerns of African Americans. She also helped share Roosevelt's messages with black voters, especially in the North where they could vote.

After she passed away, a writer named Louis E. Martin said, "She gave out faith and hope as if they were pills and she some sort of doctor."

Mary McLeod Bethune has received many honors. Her home in Daytona Beach is a National Historic Landmark. Her house in Washington, D.C. is a National Historic Site. A large statue of her was placed in Lincoln Park in Washington, D.C. in 1974. This 17-foot bronze statue was the first monument to honor an African American and a woman in a public park in Washington, D.C. In 2018, Florida chose her as one of its two statues in the National Statuary Hall Collection in the U.S. Capitol.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Mary Jane McLeod was born in 1875 in a small log cabin. This was near Mayesville, South Carolina, on a farm. She was the fifteenth of seventeen children born to Sam and Patsy McLeod. Both of her parents had been slaves. Her parents worked hard to buy a farm for their family so they could be independent.

As a child, Mary went with her mother to deliver laundry for white families. One day, she saw a book in a white child's nursery. When she tried to pick it up, the white child quickly took it away, saying Mary couldn't read. This made Mary realize that being able to read and write was a big difference between white and black people. She decided right then that she wanted to learn.

Mary went to the Trinity Mission School in Mayesville. It was a one-room school for black children. She was the only child in her family who went to school. Every day, she walked five miles to and from school. She would then teach her family what she had learned. Her teacher, Emma Jane Wilson, became a very important person in her life.

Emma Jane Wilson helped Mary get a scholarship to Scotia Seminary (now Barber-Scotia College). Mary attended from 1888 to 1893. The next year, she went to the Institute for Home and Foreign Missions in Chicago (now the Moody Bible Institute). She hoped to become a missionary in Africa. But she was told that black missionaries were not needed. So, she decided to become a teacher, because education was very important for African Americans.

Marriage and Family Life

Mary McLeod married Albertus Bethune in 1898. They moved to Savannah, Georgia, where she did social work. Later, the Bethunes moved to Florida. They had a son named Albert. A minister convinced them to move to Palatka, Florida, to run a mission school. The Bethunes moved in 1899. Mary ran the school and started helping prisoners. Albertus left the family in 1907. He never divorced Mary and moved to South Carolina. He passed away in 1918.

Teaching and School Building

Learning from Lucy Craft Laney

Mary Bethune worked as a teacher for a short time at her old elementary school. In 1896, she started teaching at Haines Normal and Industrial Institute in Augusta, Georgia. This school was founded and run by Lucy Craft Laney. Lucy Laney was also the daughter of former slaves. She ran her school with a strong Christian focus, teaching good character and practical skills to girls. She also welcomed boys who wanted to learn.

Bethune was very impressed by Lucy Laney. She said Laney was fearless and had amazing energy. Bethune learned a lot from Laney's way of teaching. She believed that educating girls and women was the best way to improve life for black people. After one year at Laney's school, Bethune moved to the Kindell Institute in Sumter, South Carolina.

Starting a School in Daytona

After she got married and moved to Florida, Bethune was determined to start a school for girls. She moved to Daytona because it had more opportunities. It was a popular place for tourists, and businesses were doing well. In October 1904, she rented a small house. She made benches and desks from old crates and got other items through donations.

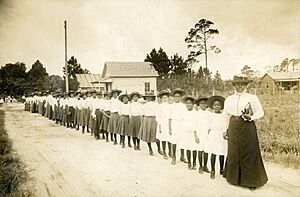

Bethune started the Educational and Industrial Training School for Negro Girls with just $1.50. She began with six students: five girls aged six to twelve, and her own son, Albert. The school was next to Daytona's dump. Bethune, the students' parents, and church members raised money by selling sweet potato pies, ice cream, and fried fish to workers at the dump.

In the beginning, students made ink from elderberry juice and pencils from burned wood. They asked local businesses for furniture. Bethune later wrote, "I considered cash money as the smallest part of my resources. I had faith in a loving God, faith in myself, and a desire to serve." The school received donations of money, equipment, and help from local black churches. Within a year, Bethune was teaching over 30 girls.

Bethune also reached out to wealthy white groups, like the Palmetto Club. She invited important white men to join her school's board of trustees. This included James Gamble (from Procter & Gamble) and Ransom Eli Olds (who started Oldsmobile cars). When Booker T. Washington visited in 1912, he told her how important it was to get support from white people who could donate money.

The school had a strict schedule. Girls woke up at 5:30 a.m. for Bible study. Classes taught home economics and practical skills like sewing, cooking, and other crafts. This helped the girls learn to be self-sufficient. Their day ended at 9 p.m. Soon, Bethune added science and business courses, and then high school subjects like math, English, and foreign languages.

Bethune was always looking for donations to keep her school running. She traveled to raise money. A donation of $62,000 from John D. Rockefeller helped a lot. Her friendship with Franklin D. Roosevelt and his wife also helped her connect with many supportive people.

In 1931, the Methodist Church helped her school merge with the Cookman Institute for boys. This created the Bethune-Cookman College, which taught both boys and girls. Bethune became its president. Even during the Great Depression, the Bethune-Cookman School continued to operate and met Florida's education standards.

From 1936 to 1942, Bethune had to spend less time as president because of her work in Washington, D.C.. Funding for the school went down during this time. But by 1941, the college had a four-year program and became a full college. By 1942, Bethune stepped down as president because her many responsibilities affected her health.

She also made the school's library open to everyone. It became Florida's first free library that black Floridians could use.

Helping the Daytona Beach Community

McLeod Hospital

In the early 1900s, there was no hospital in Daytona Beach, Florida, that would treat black people. Bethune decided to start a hospital after one of her students became very sick with appendicitis. The student needed immediate medical help, but no local hospital would take her because she was black. Bethune demanded that a white doctor at the local hospital help the girl. When Bethune visited her student, she was told to use the back door. She found her student neglected and placed on an outdoor porch.

Because of this experience, Bethune knew the black community in Daytona needed its own hospital. She found a cabin near the school. With help from sponsors who raised money, she bought it for five thousand dollars. In 1911, Bethune opened the first black hospital in Daytona, Florida. It started with two beds and grew to twenty beds within a few years. Both white and black doctors worked at the hospital, along with Bethune's student nurses. This hospital saved many black lives during the twenty years it was open.

During that time, both black and white people in the community relied on McLeod Hospital. After an explosion at a nearby construction site, the hospital treated injured black workers. The hospital and its nurses were also praised for their work during the 1918 influenza outbreak. The hospital was so full during this time that patients overflowed into the school's auditorium. In 1931, Daytona's public hospital, Halifax, agreed to open a separate hospital for people of color. Black people were not fully integrated into the main public hospital until the 1960s.

A Leader for Change

Working for Voting Rights

After the Nineteenth Amendment was passed, giving women the right to vote, Bethune continued to help black people gain access to voting. She collected donations to help black voters pay poll taxes. These taxes were used to stop black people from voting. She also offered tutoring for the literacy tests that people had to pass to register to vote. She organized large events to help people register to vote.

National Association of Colored Women

In 1896, the National Association of Colored Women (NACW) was created to support black women. Bethune was the president of the Florida chapter of the NACW from 1917 to 1925. She worked to register black voters, which was very difficult because of laws and practices in Florida that tried to stop them. She even faced threats from the Ku Klux Klan during these years. Bethune also led the Southeastern Federation of Colored Women's Clubs from 1920 to 1925. This group worked to create more opportunities for black women.

She was elected as the national president of the NACW in 1924. Bethune wanted the organization to have its own headquarters and a full-time secretary. She made this happen when the NACW bought a building in Washington, D.C. This made it the first black-led organization to have its headquarters in the nation's capital.

Bethune became well-known across the country. In 1928, she was invited to a conference by President Calvin Coolidge. In 1930, President Herbert Hoover appointed her to another important conference about child health.

National Council of Negro Women

In 1935, Bethune founded the National Council of Negro Women (NCNW) in New York City. She brought together leaders from 28 different organizations. Their goal was to improve the lives of black women and their communities. Bethune said the council wanted to help America become a true and free democracy by including all people, no matter their race or background.

In 1938, the NCNW hosted a conference at the White House about black women and children. This showed how important black women were in American society. During World War II, the NCNW helped black women become officers in the Women's Army Corps. Bethune also served as a special assistant to the Secretary of War during the war.

Today, the NCNW headquarters is on Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, D.C. The building where Bethune once lived and where the NCNW used to be located is now a National Historic Site.

National Youth Administration

The National Youth Administration (NYA) was a government agency created by President Roosevelt. It helped young people find jobs and get training. It focused on unemployed people aged sixteen to twenty-five who were not in school. Bethune worked very hard to get the NYA to include minorities. Her efforts were so successful that she got a full-time job as an assistant in 1936.

Within two years, Bethune was made Director of the Division of Negro Affairs. She was the first African-American woman to lead a division like this. She managed NYA funds to help black students through school programs. She was the only black person in the NYA who managed money. She also made sure black colleges were part of the Civilian Pilot Training Program, which trained some of the first black pilots. The director of the NYA said in 1939, "No one can do what Mrs. Bethune can do."

Bethune's strong will helped national leaders see the need to create more jobs for black youth. The NYA's final report in 1943 stated that over 300,000 black young people got jobs and training through NYA projects. These projects helped them qualify for jobs they couldn't get before.

Bethune also pushed for black NYA officials to get important political positions. Her assistants helped connect the national office with state and local NYA agencies. This large team helped create better job and salary opportunities for black people across the country. The NYA ended in 1943.

The Black Cabinet

- Further information: Black Cabinet

Bethune became a close friend of Eleanor and Franklin Roosevelt. At a conference in 1938, Eleanor Roosevelt chose to sit next to Bethune, even though state laws at the time required segregation. Eleanor Roosevelt often called Bethune "her closest friend in her age group." Bethune told black voters about the good things the Roosevelt Administration was doing for them. She also shared their concerns with the Roosevelts. She had special access to the White House because of her friendship with the First Lady.

She used this access to create a group of black leaders called the Federal Council of Negro Affairs. This group advised the Roosevelt administration on issues facing black people in America. It was made up of many talented black individuals, mostly men, who had been appointed to jobs in federal agencies. This was the first time so many black people worked in high government positions together.

The Black Cabinet showed voters that the Roosevelt administration cared about black concerns. The group met informally and influenced political appointments and how money was given to organizations that helped black people.

Civil Rights Work

In 1931, the Methodist Church supported the merger of the Daytona Normal and Industrial School and the Cookman College for Men. This created Bethune-Cookman College. Bethune was a member of the Methodist Church, but it was segregated in the South. She worked to integrate the mostly white Methodist Episcopal Church.

Bethune worked to teach both white and black people about the achievements and needs of black people. In 1938, she wrote, "If our people are to fight their way up out of bondage we must arm them with the sword and the shield and buckler of pride – belief in themselves and their possibilities, based upon a sure knowledge of the achievements of the past."

A year later, she wrote that not only black children, but children of all races, should learn about the achievements of black people. She believed that understanding all cultures helps create world peace and brotherhood.

On Sundays, she opened her school to tourists in Daytona Beach. She showed off her students' accomplishments and hosted national speakers on black issues. She made sure these Community Meetings were integrated. A black teenager from Daytona at the time remembered that many tourists attended and sat wherever there were empty seats, with no special section for white people.

When the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education (1954) that segregation in public schools was against the law, Bethune supported the decision. She wrote that there could be no "divided democracy" or "class government." She believed there should be no discrimination or segregation. She said, "We are on our way. But these are frontiers which we must conquer. ... We must gain full equality in education ... in the franchise ... in economic opportunity, and full equality in the abundance of life."

Bethune also organized the first officer candidate schools for black women. She spoke to federal officials, including Roosevelt, to help African-American women who wanted to join the military.

United Negro College Fund

She helped start the United Negro College Fund (UNCF) on April 25, 1944. She worked with William J. Trent and Frederick D. Patterson. The UNCF provides scholarships, mentorships, and job opportunities to African American and other minority students. These students attend historically black colleges and universities. By 1964, the UNCF had raised over $50 million.

Personal Life and Legacy

Mary McLeod Bethune had a dark complexion. She often carried a cane, not because she needed it to walk, but because she said it gave her "swank." Bethune often said that her school and students in Daytona were her first family. Her students often called her "Mama Bethune."

She was known for achieving her goals. Dr. Robert C. Weaver, who also worked in Roosevelt's Black Cabinet, said she had a way of seeming helpless to get what she wanted, but she was actually very determined. When a white resident in Daytona threatened Bethune's students with a rifle, Bethune worked to make him an ally. He ended up protecting the children and even said he would protect "old Mary" with his life.

She believed in being self-sufficient throughout her life. Bethune invested in several businesses, including the Pittsburgh Courier, a black newspaper, and life insurance companies. She also started Central Life Insurance of Florida. Because of segregation laws, black people were not allowed to visit the beach. Bethune and other business owners bought a two-mile stretch of beach called Paradise Beach. They sold properties there to black families and also allowed white families to visit. Later, Paradise Beach was renamed Bethune-Volusia Beach in her honor.

Honors and Recognition

In 1930, a journalist named Ida Tarbell listed Bethune as one of America's greatest women. Bethune received the Spingarn Medal in 1935 from the NAACP.

In the 1940s, Bethune used her influence and friendship with Eleanor Roosevelt to help Eddie Durham's All-Star Girl Orchestra, an all-women's swing band, travel in luxury buses.

Bethune was the only black woman present at the founding of the United Nations in San Francisco in 1945. She represented the NAACP. In 1949, she became the first woman to receive Haiti's highest award, the National Order of Honour and Merit. She also served as the U.S. representative for the induction of President William V.S. Tubman of Liberia in 1949.

She also advised five U.S. presidents. Calvin Coolidge and Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed her to several government positions. She was an honorary member of the Delta Sigma Theta sorority.

In 1973, Bethune was added to the National Women's Hall of Fame. On July 10, 1974, a large statue of her was put up in Lincoln Park (Washington, D.C.). It was the first monument in a public park in Washington, D.C., to honor an African American or a woman. Thousands of people attended the unveiling ceremony. The money for the monument was raised by the National Council of Negro Women.

The statue has an inscription that says, "let her works praise her." On the side, there is a passage from her "Last Will and Testament," which shares her hopes for the future:

I leave you to love. I leave you to hope. I leave you the challenge of developing confidence in one another. I leave you a thirst for education. I leave you a respect for the use of power. I leave your faith. I leave you racial dignity. I leave you a desire to live harmoniously with your fellow men. I leave you a responsibility to our young people.

In 1985, the U.S. Postal Service issued a stamp in Bethune's honor. In 1989, Ebony magazine listed her as one of "50 Most Important Figures in Black American History." In 1999, Ebony included her as one of the "100 Most Fascinating Black Women of the 20th century." In 1991, a crater on the planet Venus was named in her honor by the International Astronomical Union.

In 1994, the National Park Service bought Bethune's last home, which was also the NACW Council House. It was named the Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site.

Many schools across the United States have been named in her honor.

In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante listed Bethune on his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.

In 2004, Bethune-Cookman University celebrated its 100th anniversary. A street next to the university was renamed Mary McLeod Bethune Boulevard. The university's website says that her vision continues to guide them. A vice president of the university recalled her legacy: "During Mrs. Bethune's time, this was the only place in the city of Daytona Beach where Whites and Blacks could sit in the same room and enjoy what she called 'gems from students'—their recitations and songs. This is a person who was able to bring Black people and White together."

A historical marker in Mayesville, Sumter County, South Carolina, marks her birthplace.

In 2018, the Florida Legislature chose her as the subject of one of Florida's two statues in the National Statuary Hall Collection in the U.S. Capitol.

The Mary McLeod Bethune Scholarship Program helps Floridian students attend historically black colleges and universities in the state.

A statue of Bethune in Jersey City, New Jersey, was dedicated in 2021.

A statue of Mary McLeod Bethune was unveiled on July 13, 2022, in the United States Capitol. This made her the first black American represented in the National Statuary Hall Collection.

See also

In Spanish: Mary McLeod Bethune para niños

In Spanish: Mary McLeod Bethune para niños

- African-American history

- African-American literature

- List of African-American writers

- List of people on stamps of the United States

| Tommie Smith |

| Simone Manuel |

| Shani Davis |

| Simone Biles |

| Alice Coachman |