Women's suffrage in Alabama facts for kids

In Alabama, women worked for many years to gain the right to vote. This movement is called women's suffrage. It started in the 1860s. A woman named Priscilla Holmes Drake was very important in these early efforts.

Over time, different groups formed to support women's voting rights. One major group was the Alabama Woman Suffrage Organization (AWSO). In 1901, Alabama held a meeting to write a new state constitution. Women who supported suffrage spoke up, hoping to include women's rights. But the new constitution still did not allow women to vote.

The suffrage movement slowed down for a few years. Then, in the 1910s, new groups started up. Women in Alabama first tried to change their state's laws. When that didn't work, they supported a national change. This was the push for the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. This amendment would give women across the country the right to vote. Alabama did not officially approve this amendment until 1953.

For many years, both white and African American women faced challenges voting. They had to pay poll taxes. Black women also faced literacy tests and threats. African American women could not fully use their right to vote until the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was passed.

Contents

Early Steps for Women's Voting Rights

For a long time, the fight for women's voting rights in Alabama was mostly led by Priscilla Holmes Drake. She and her husband moved to Huntsville, Alabama in 1861. Priscilla Drake was Alabama's only representative to the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) in the 1860s. Many women in Alabama in the late 1800s were also involved in the temperance movement. This movement worked to reduce alcohol use. Women soon realized they needed the right to vote to help solve social problems in their state.

In 1890, a newspaper called the New Decatur Advertiser started printing articles about women's suffrage. The first women's suffrage group in Alabama began in New Decatur in 1892. It was led by Ellen Stephens Hildreth. Another group formed in Verbena, Alabama that same year, led by Emera Frances Griffin. The next year, Hildreth and Griffin started a statewide group. It was called the Alabama Woman Suffrage Organization (AWSO).

Sisters Frances John Hobbs and Mary Amelia John Watson in Selma also worked for women's voting rights. They created the Selma Suffragette Association. Their work inspired other women in Selma, like Carrie McCord Parke. In 1894, the Huntsville League for Woman Suffrage was formed. Famous suffrage leaders Susan B. Anthony and Carrie Chapman Catt visited Alabama in 1895. They spoke to different women's suffrage groups. Their visit helped the new Huntsville group grow. However, a financial problem in the state in 1896 slowed down the suffrage work. Still, by 1897, cities like Calera, Gadsden, and Jasper had women's suffrage groups.

In 1901, Emera Frances Griffin spoke at the Alabama state meeting to create a new constitution. She spent a lot of time in Montgomery, Alabama. She tried to convince the leaders to include women's rights in the new constitution. She was known as a great speaker with a good sense of humor. Some people at the meeting thought giving women the right to vote would help control the votes of Black men. But despite Griffin's efforts, the Alabama Constitution was approved without giving women any new rights. After 1901, the women's suffrage movement in Alabama paused for several years.

New Efforts for Women's Suffrage

The fight for women's voting rights in Alabama became active again in the 1910s. In 1910, Mary Partridge started the Selma Suffrage League. In 1911, Jane Addams and Jean Gordon spoke in Birmingham. Their speeches inspired Pattie Ruffner Jacobs and other women. They formed the Birmingham Equal Suffrage League on October 22, 1911. These two groups were the strongest voices for suffrage at the time.

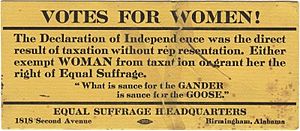

In 1912, Alabama suffragists decided to create a statewide group. On October 9, the Alabama Equal Suffrage Association (AESA) was formed. AESA joined with the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). Pattie Ruffner Jacobs was the first president. Mary Partridge was elected vice-president. AESA set up its main office in Birmingham. The group worked to promote women's suffrage. They also created helpful resources. AESA had a traveling library of suffrage materials. Their office was a place for women to meet in the city. The Huntsville Equal Suffrage Association was created in 1912. This happened after Jacobs asked for more local groups to form.

AESA held its first big meeting in Selma in January 1913. They knew that Joseph Green, a state representative, wanted to introduce a bill for women's suffrage in 1915. Women in Alabama hoped their state could be the first Southern state to give women the right to vote. In 1914, more women's suffrage groups formed in Alabama. Representatives from all over the state attended the second state suffrage meeting in Huntsville on February 5. In 1914, Bossie O'Brien Hundley started working to convince state lawmakers to support women's suffrage.

In January 1915, a bill for a women's suffrage amendment was introduced. It was sent to a committee and stayed there until July. Suffragists worked hard to get the committee to vote on the bill. Green and Senator Sam Will John brought the bill to a vote on August 25. Two days before the vote, a group against suffrage published a pamphlet. It was given to all lawmakers. Green, who introduced the bill, even changed his mind and stopped supporting it. The suffrage bill did not get enough votes to pass.

The 1917 state suffrage meeting was held on February 12 and 13. About 81 women's suffrage clubs were reported at the meeting. After the meeting, a suffrage school was held. Members of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) taught 200 Alabama women. In 1917, when the United States entered World War I, AESA helped with the war effort. Many suffrage groups did this.

The Fight to Approve the Amendment

Women fighting for suffrage in Alabama started to believe their best chance was to support a national amendment. In 1917, Pattie Ruffner Jacobs publicly supported a national amendment for women's voting rights. At the 1918 state meeting in Selma, AESA officially decided to support the national amendment.

In June 1919, AESA began a campaign to support the Nineteenth Amendment. AESA created a special committee. They found volunteers to organize, campaign, and talk to lawmakers. AESA also got help from NAWSA. NAWSA sent suffrage materials and organizers to Alabama.

The state legislature considered the Nineteenth Amendment in July 1919. Suffragists from all over Alabama traveled to Montgomery. They wanted to convince lawmakers to vote for women's suffrage. The Women's Anti-Ratification League strongly opposed the amendment. Marie Bankhead Owen was a leader of this group. Senators Oscar W. Underwood and John H. Bankhead also spoke against the amendment. On July 17, the state senate voted no. In August, the state house also voted no.

At the last state suffrage meeting in April 1920, the AESA was closed. The League of Women Voters (LWV) of Alabama was then formed. After the Nineteenth Amendment was approved nationwide, suffragists in Alabama held a victory parade in Birmingham. Women from all over Jefferson County were invited to march on September 4. About 1,500 suffragists marched with 36 cars and a band. Alabama did not officially approve the Nineteenth Amendment until September 8, 1953.

Continued Efforts for Voting Rights

Even after women in Alabama gained the right to vote with the Nineteenth Amendment, many white women still couldn't vote. This was because of Alabama's poll tax. The poll tax was a fee people had to pay to vote. It was hard for some women to pay this tax. Many voters also owed "back taxes" from previous years. Some people thought white women didn't vote much because they weren't interested in politics. However, Minnie Steckel studied Alabama women voters in 1937. She found that the poll tax affected white women more than men. Black women were also affected by the poll tax.

The Women's Division of the Democratic National Committee learned about this problem. Mary Dewson and Eleanor Roosevelt led this division. They started to find local women to fight the poll tax. On October 26, 1938, May Thompson Evans spoke to Alabama women Democrats. She urged them to fight the poll tax. Evans said that women were losing their right to vote. She also suggested that if white women couldn't vote, it would threaten white supremacy in Alabama. Women in professional groups in Alabama worked to change local poll tax laws during the 1930s.

Virginia Foster Durr and the Women's Division gathered more information on the poll tax. Durr also helped start the National Committee to Abolish the Poll Tax (NCAPT). Another study in 1942 showed that white women were unfairly prevented from voting because of the poll tax. Attempts to pass national laws banning poll taxes failed between 1942 and 1949. At the local level, white Alabama women continued to fight the poll tax. They talked to lawmakers. A bill passed in 1944 that excused service members and Veterans from the poll tax. This showed that the tax affected women more than men. By the late 1940s, white women in Alabama realized they also had to deal with the issue of racial unfairness and the poll tax.

In 1953, a bill was passed to reduce how many years of back taxes people had to pay. Voters approved this bill. This allowed many more white women to register to vote. The fight over the poll tax continued into the 1960s. Finally, the Twenty-Fourth Amendment was approved in 1964. This ended the poll tax in Alabama.

African American Women and Voting Rights

White women who supported suffrage in Alabama often argued that giving women the right to vote would not help African-American women. Instead, they claimed that white women's votes would "cancel out" the votes of Black men. White women in Alabama used this idea to try to convince politicians that women's suffrage was a good thing.

Much of the work for African American voting rights happened through Black women's clubs. In 1910, the Alabama Federation of Colored Women's Clubs (AFCWC) supported women's suffrage. In Tuskegee, Alabama, Black women worked on many issues to improve their community. Margaret Murray Washington led the Tuskegee Women's Club. This club was connected to the Tuskegee Institute. The club helped provide education that many African Americans could not otherwise get.

Adella Hunt Logan was a Black woman who could sometimes be seen as white. This allowed her to attend suffrage meetings across Alabama. Logan also led the suffrage department of the National Association of Colored Women's Clubs (NACWC). She was also the only lifetime member of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) from Alabama. Logan wrote a lot about women's suffrage. She owned a very large library of suffrage materials.

After the Nineteenth Amendment passed, Black women still faced challenges voting. Voters had to fill out a long application form. They had to swear an oath, pass a literacy test, and pay a poll tax. Indiana Little led a protest march of about 1,000 Black men and women. They marched to Birmingham's voting office because Black people were given unfair intelligence tests. She was arrested. Some counties in Alabama had a "voucher system." This meant another registered voter had to "vouch for" new voters. Black voters also knew that if they registered publicly, the KKK would know. This process was meant to scare Black voters. Black women also faced segregation. The Montgomery League of Women Voters (LWV) refused to allow Black members in the 1940s. In response, Black leaders created the Women's Political Council (WPC).

The Twenty-fourth Amendment ended poll taxes across the United States. It was fully approved on January 23, 1964. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 gave African American women much better access to the right to vote. By 1967, the number of registered Black voters greatly increased.

People Against Women's Suffrage

Many men in the South believed it was wrong for women to vote or be involved in politics. Women's suffrage was also seen as a "radical" or extreme idea by many women in the South.

When the Nineteenth Amendment was sent to the states for approval, people in Alabama who were against suffrage became very active. In 1919, the Alabama Woman's Anti-Ratification League (AWARL) was formed. AWARL argued that allowing women to vote would weaken the Alabama Constitution. They were also worried that women's suffrage would threaten white supremacy in Alabama.

|