Frances Wright facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Frances Wright

|

|

|---|---|

1824 portrait of Wright by Henry Inman

|

|

| Born | September 6, 1795 |

| Died | December 13, 1852 (aged 57) |

| Nationality | American, Scottish |

| Occupation | Writer, lecturer, abolitionist, social reformer |

| Known for | Feminism, free thinking, utopian community founder |

| Spouse(s) | Guillaume Phiquepal D'Arusmont |

| Children | Francès-Silva D'Arusmont Phiquepal |

Frances Wright (born September 6, 1795 – died December 13, 1852), often called Fanny Wright, was a Scottish-born writer, speaker, and social reformer. She was a freethinker, meaning she believed in forming opinions based on reason, not just tradition or religion. She was also a feminist, working for equal rights for women.

In 1825, she became a U.S. citizen. That same year, she started a special community called the Nashoba Commune in Tennessee. It was a utopian community, meaning it aimed to be a perfect society. Her goal was to show how enslaved people could be prepared for freedom. However, the project only lasted five years.

In the late 1820s, Frances Wright was one of the first women in America to speak publicly about politics and social changes. She spoke to groups of both men and women. She believed everyone should have a good education. She also fought for the freedom of enslaved people, equal rights for all, and fair laws for married women and divorce.

Wright also spoke out against organized religion and the death penalty. Many people, especially religious leaders and newspapers, strongly criticized her ideas. Her public talks in the United States led to groups called "Fanny Wright societies." She also worked closely with the Working Men's Party in New York City. Her influence was so strong that opponents called their candidates the "Fanny Wright ticket."

Frances Wright was also a talented writer. Her book, Views of Society and Manners in America (1821), was a popular travel book about the United States. She also wrote A Plan for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery in the United States (1825). She helped edit newspapers like The New Harmony and Nashoba Gazette.

Contents

Early Life and Learning

Frances "Fanny" Wright was born in Dundee, Scotland, on September 6, 1795. Her parents were Camilla Campbell and James Wright. Her father was a wealthy linen maker and a political radical. This meant he supported big changes in government and society. He even knew famous thinkers like Adam Smith.

Frances was the second of three children. Her older brother died young, and her mother also passed away early. Her father died in 1798 when Frances was only two years old. Frances and her sister, Camilla, became orphans. They were raised in England by their mother's relatives, the Campbell family. They had enough money from their inheritance to live comfortably.

A maternal aunt became Frances's guardian. She taught Frances ideas based on the philosophy of the French materialists. In 1813, at age sixteen, Frances moved back to Scotland. She lived with her great-uncle, James Mylne, a philosophy professor. Frances spent winters studying and writing. In the summers, she explored the Scottish Highlands. She loved the works of Greek philosophers, especially Epicurus. Her first book, A Few Days in Athens (1822), was about Epicurus. She wrote it when she was just eighteen. Frances also studied history and became very interested in the United States' democratic government.

First Trips to America and France

In 1818, twenty-three-year-old Frances Wright and her younger sister Camilla visited the United States for the first time. They traveled around the country for two years before returning to England. While Frances was in New York City, her play Altorf was performed. It was about Switzerland's fight for independence. The play opened in February 1819.

Soon after returning to England in 1820, Wright published Views of Society and Manners in America (1821). This book was a big moment in her life. It led to an invitation from Jeremy Bentham to join his group of friends. This group included important thinkers who were against religious leaders. This influenced Wright's own ideas.

In 1821, Wright went to France after being invited by the Marquis de Lafayette. They met in Paris and became good friends, even though he was much older. At one point, Wright asked him to adopt her and her sister. This caused some tension with Lafayette's family, and the adoption did not happen. However, their friendship continued. She even returned to Lafayette's home in France in 1827 to work on his biography.

Second Visit to the United States

In 1824, Wright and her sister came back to the United States. They followed the Marquis de Lafayette during his farewell tour of the country. Wright stayed with Lafayette for two weeks at Monticello, Thomas Jefferson's home in Virginia. Through Lafayette, Wright met other important figures like Presidents James Madison and John Quincy Adams, and General Andrew Jackson.

In February 1825, Wright traveled to Harmonie, a utopian community in Pennsylvania. She also visited another community in Indiana called Harmonie. This Indiana community had just been sold to Robert Owen, who renamed it New Harmony. Wright's visits to these communities inspired her to create her own experimental community in Tennessee. After leaving Indiana, she traveled down the Mississippi River to meet Lafayette in New Orleans in April 1825. When Lafayette went back to France, Wright decided to stay in the United States. She continued her work as a social reformer and became a U.S. citizen in 1825.

Frances Wright's Beliefs

Frances Wright strongly believed in equal opportunities for everyone, especially in education. She was a strong supporter of feminism, which means equal rights for women. She did not agree with organized religion, traditional marriage, or capitalism.

Education was very important to her. Along with Robert Owen, she pushed for the government to offer free public education for all children. She also believed in equal rights for all people. She wanted married women to have more legal rights and for divorce laws to be fair. She was a strong advocate for freeing enslaved people. She even supported the idea of interracial marriages, which was very controversial at the time.

Wright tried to show her ideas through her community project in Tennessee. She believed that the progress of society depended on the progress of women. Her opposition to slavery was different from many other politicians of her time, especially those in the South. Her work for working-class men also set her apart from other abolitionists.

Frances Wright's Career

Early Writing

Frances Wright's early writing included her book, Few Days in Athens (1822). This book defended the ideas of the philosopher Epicurus. She wrote it before she was eighteen. Her book Views of Society and Manners in America (1821) was a memoir of her first visit to the United States. In it, she enthusiastically supported America's democratic system. This book gave early descriptions of American life. It was translated into several languages and read by many reformers in Great Britain, the United States, and Europe.

The Nashoba Experiment

In early 1825, after visiting Thomas Jefferson's home and Robert Owen's New Harmony community, Wright began planning her own experimental farming community. By the summer of 1825, she was seeking advice from Lafayette and Jefferson. Owen and Lafayette later joined her project's board, but Jefferson chose not to participate. Wright also published A Plan for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery in the United States (1825). She hoped this would convince the U.S. Congress to set aside federal land to help end slavery.

To show how enslaved people could be freed without their owners losing money, Wright started a model farming community in Tennessee. Enslaved people would work to earn money to buy their freedom and receive an education.

In the fall of 1825, Wright traveled to Tennessee and bought about 320 acres of land near Memphis. She founded a community there called Nashoba. To prove her idea could work, she bought about thirty enslaved people, nearly half of them children. Her plan was for them to gradually gain their freedom through their work on the property. Wright also planned to help the newly freed people move to areas outside the United States.

Wright planned to build cabins, farm buildings, and a school for Black students. Many abolitionists, however, criticized her idea of gradual freedom and training for former enslaved people. Wright helped clear land and build log cabins for everyone living there, both Black and white.

However, Nashoba faced problems from the start. It was built on land with many mosquitoes, which caused malaria. The farm also struggled to produce good harvests. Wright herself got malaria in the summer of 1826 and had to leave to recover. While she was away, the community declined. The temporary managers began treating the Black workers more harshly.

Wright returned to Nashoba in 1828 with her friend, Frances Trollope. Trollope spent ten days there and found the community in disarray and close to financial ruin. Trollope later wrote about the poor weather, lack of beauty, and how remote Nashoba was.

In 1828, as Nashoba was failing, Wright published an explanation and defense of the community in the New-Harmony Gazette. In January 1830, Wright hired a ship and took the community's thirty enslaved people to Haiti. Haiti had become independent in 1804, and they could live there as free men and women. The failed experiment cost Wright about US$16,000. Today, Germantown, a suburb of Memphis, stands on the land where Nashoba once was.

Newspaper Editor

After the Nashoba experiment failed in the late 1820s, Frances Wright returned to New Harmony, Indiana. There, she became the co-editor of The New Harmony and Nashoba Gazette. This newspaper was later renamed the Free Enquirer. She worked with Robert Dale Owen, the eldest son of Robert Owen, who founded the New Harmony community. In 1829, Wright and Robert Dale Owen moved to New York City. They continued to edit and publish the Free Enquirer there. Wright also edited The Sentinel, which later became New York Sentinel and Working Man's Advocate.

Political and Social Activist

Starting in the late 1820s and early 1830s, Frances Wright began speaking publicly. She supported ending slavery and giving women the right to vote. She also campaigned for changes to marriage and property laws. In New York City, she bought a former church and turned it into a "Hall of Science" for lectures.

From 1833 to 1836, her talks on slavery and other social issues drew large, excited crowds of men and women. These talks happened in the eastern United States and the Midwest. This led to the creation of "Fanny Wright societies." Even though her lectures were popular, her strong views were often met with opposition. She published a collection of her speeches in her book, Course of Popular Lectures (1829 and 1836).

Newspapers and religious leaders often criticized Wright and her opinions. For example, the New York American called her "a female monster" because of her controversial views. But she was not discouraged. As her ideas became even more radical, she left the Democratic Party. She joined the Working Men's Party, which was formed in New York City in 1829. Her influence on this party was so strong that opponents called their candidates the "Fanny Wright ticket." Wright also supported the American Popular Health Movement in the 1830s. She believed women should be involved in health and medicine.

Personal Life

Frances Wright married a French doctor named Guillaume D'Arusmont in Paris, France, on July 22, 1831. She had first met him at New Harmony, Indiana, where he was a teacher. D'Arusmont also went with her to Haiti in 1830, helping her with business. Their daughter, Francès-Sylva Phiquepal D'Arusmont, was born on April 14, 1832.

Later Years

Wright, her husband, and their daughter traveled to the United States in 1835. They made several trips between the United States and Europe. Wright eventually settled in Cincinnati, Ohio. She bought a home there in 1844 and tried to restart her career as a lecturer. She continued to travel and give talks, but her appearances and views were not always welcomed. She also became a supporter of President Andrew Jackson. After a political campaign in 1838, Wright began to suffer from various health problems. She published her final book, England, the Civilizer, in 1848.

Wright divorced D'Arusmont in 1850. She also had a long legal fight to keep custody of their daughter and control her own money. The legal issues were still not settled when Wright died. Frances Wright spent her last years quietly in Cincinnati, separated from her daughter, Francès-Sylva D'Arusmont.

Death and Legacy

Frances Wright died on December 13, 1852, in Cincinnati, Ohio. She passed away from problems after breaking her hip in a fall on ice outside her home. She is buried at the Spring Grove Cemetery in Cincinnati. Her daughter, Francès-Sylva D'Arusmont, inherited most of Wright's money and property.

Frances Wright was an early supporter of women's rights and a social reformer. She was the first woman to give public lectures to both men and women on political and social issues in the United States in the late 1820s. Her ideas about slavery, religion, and women's rights were considered very radical for her time. They brought her harsh criticism from newspapers and religious leaders.

Honors and Memorials

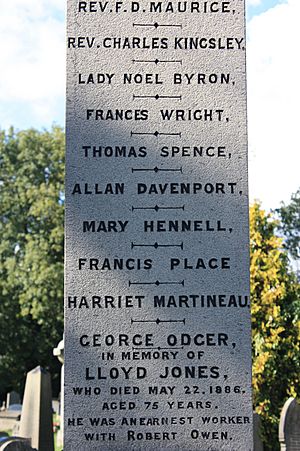

- Frances Wright's name is on the Reformers Memorial in Kensal Green Cemetery in London.

- A plaque was placed on the wall of her birthplace at 136 Nethergate in Dundee, Scotland.

- Wright was added to the National Women's Hall of Fame in 1994.

Selected Published Works

- Altorf: A Tragedy (Philadelphia, 1819)

- Views on Society and Manners in America (London, 1821)

- A Few Days in Athens (London, 1822)

- A Plan for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery in the United States (1825)

- Lectures on Free Inquiry (New York, 1829; 6th ed., 1836)

- Address on the State of the Public Mind and the Measures Which it Calls For (New York, 1829)

- Course of Popular Lectures (New York, 1829 and 1836)

- Explanatory Notes Respecting the Nature and Objects of the Institution of Nashoba (1830)

- What is the Matter? A Political Address as Delivered in Masonic Hall (1838)

- Fables (London, 1842)

- Political Letters, or, Observations on Religion and Civilization (1844)

- England the Civilizer: Her History Developed in Its Principles (1848)

- Biography, Notes, and Political Letters of Frances Wright D'Arusmont (1849)

See also

In Spanish: Frances Wright para niños

In Spanish: Frances Wright para niños

- Robert Owen

- Robert Dale Owen

- New Harmony, Indiana

- Popular Health Movement

- Working Men's Party

- Fanny Trollope

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |