Women's suffrage in states of the United States facts for kids

Women's suffrage means women having the right to vote. In the United States, women started getting this right in different towns, counties, states, and territories during the late 1800s and early 1900s. As women gained the right to vote in some places, they also began to run for public office. They became school board members, county clerks, state lawmakers, judges, and even members of Congress, like Jeannette Rankin.

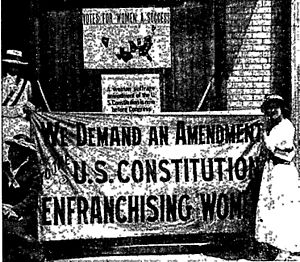

At the same time, there was a big effort to add an amendment to the U.S. Constitution. This amendment would give all women across the country the right to vote. This effort was successful when the Nineteenth Amendment was approved in 1920.

Contents

- How the Fight for Voting Rights Began

- Voting Rights Across the United States

- Western States Lead the Way

- Northeast: A Hard-Fought Battle

- Midwest: Progress and Setbacks

- Southern States: A Different Approach

- Alabama's Long Road to Ratification

- Arkansas's Primary Election Victory

- Delaware's Close Call

- Florida's City-Level Progress

- Georgia's Delayed Voting Rights

- Kentucky's Early School Suffrage

- Maryland's Delayed Ratification

- South Carolina's Late Start

- Tennessee's Decisive Vote

- Texas's Primary Election Success

- Virginia's Fight for Equality

- West Virginia's Tie-Breaking Vote

- Former Territories Gain Voting Rights

How the Fight for Voting Rights Began

The demand for women's right to vote grew stronger in the 1840s. It was part of a larger movement for women's rights. The Seneca Falls Convention in 1848 was the first meeting about women's rights. At this meeting, people debated and supported the idea of women voting. By the time of the National Women's Rights Convention in 1851, the right to vote had become a main goal of the movement.

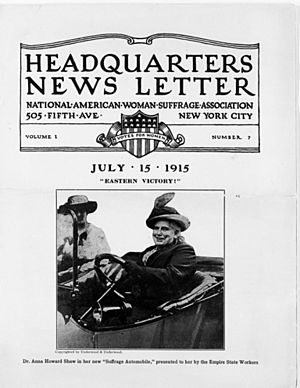

The first national groups for women's suffrage started in 1869. Two different groups were formed, and both worked to get voting rights at state and national levels. The National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) was led by Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. They especially wanted a national amendment for suffrage. The American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA), led by Lucy Stone, focused more on getting voting rights at the state level. In 1890, these two groups joined together to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA).

At the start of the 1900s, it seemed unlikely that a national amendment would pass, and progress in states had slowed down. However, in the 1910s, the push for a national amendment became strong again. The movement also had many successes in different states. A new group called the National Woman's Party (NWP), led by Alice Paul, focused almost entirely on the national amendment. The larger NAWSA, led by Carrie Chapman Catt, also made the suffrage amendment its main goal. In September 1918, President Wilson spoke to the Senate, asking them to approve the suffrage amendment. Congress approved the amendment in 1919, and enough states approved it a year later.

Voting Rights Across the United States

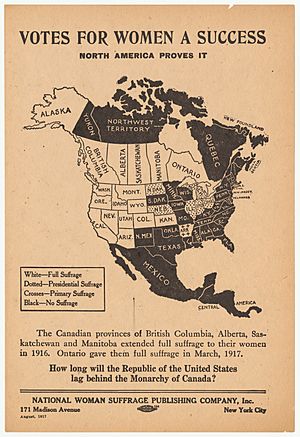

Western States Lead the Way

Generally, states and territories in the western U.S. were more open to women's voting rights than eastern states. Some people think that western areas, which had fewer women, offered voting rights to encourage more women to move there. Others thought it was a reward for the women already living there. Susan B. Anthony believed western men were more polite. In 1871, Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton visited several western states, especially Wyoming and Utah, where women already had equal voting rights. Their speeches were often made fun of or criticized by politicians, ministers, and newspaper editors. Anthony returned to the West several times, and by her last trip in 1896, her ideas were more popular and respected. Activists focused on just the voting issue and talked directly to leaders to educate and convince them.

By 1920, when women across the country gained the right to vote, women in Wyoming had already been voting for 50 years.

Arizona's Path to Voting

Early supporters of women's rights in Arizona were part of the WCTU (Woman's Christian Temperance Union). Leaders like Josephine Brawley Hughes and Frances Willard visited Arizona in the 1880s to get more members. The WCTU helped pass several women's rights laws. In 1891, women's suffrage almost became part of Arizona's new constitution, but it failed by three votes. After this, Hughes and Mrs. E. D. Garlick started the Arizona Suffrage Association. In 1897, a law passed that allowed women to vote in school board elections. Other women's suffrage bills in 1899 and 1901 did not pass. The movement slowed down after 1905.

When Arizona was likely to become a state, NAWSA started campaigning there in 1909. They sent Laura Clay and Frances Munds to talk to the state legislature, but suffrage bills still failed. Laura Gregg came in 1910 and organized suffrage groups, including Mormon women. Activists formed the Arizona Equal Suffrage Association (AESA) with Munds as president. They started a campaign to win the vote. During the 1910 constitutional convention, suffragists filled the audience, and Gregg brought a petition with 3,000 signatures. Their efforts failed because people worried that if women's suffrage was in the constitution, Arizona wouldn't become a state.

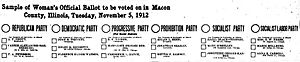

When Arizona became a state in February 1912, suffragists immediately worked to get a women's suffrage vote on the ballot. Activists traveled across the state and got enough signatures. They even translated their materials into Spanish. AESA got support from other groups and political leaders. NAWSA also sent speakers and money. AESA spoke to both Republican and Democratic state conventions to ask for their support. These actions worked, and men voted for women's suffrage in the election on November 5, 1912.

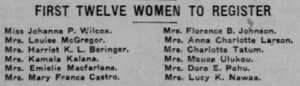

Women first registered to vote in 1913 and voted in the state primary elections in 1914. Arizona approved the Nineteenth Amendment on February 12, 1920.

California's Voting Milestone

California voters gave women the right to vote in 1911 by approving Proposition 4. Many women and men were part of this campaign. Clara Elizabeth Chan Lee was the first Chinese American woman to vote in the United States. She registered in California on November 8, 1911.

Colorado's Early Success

Former governor John Evans supported women's suffrage in Colorado's legislature in 1868. Governor Edward M. McCook proposed it again in 1870. A women's suffrage group formed in 1876 and spoke at the state's constitutional convention. Women didn't get full voting rights then, but they could vote in school board elections. A vote for full suffrage was held on October 2, 1877, but it was defeated. Activists kept fighting, forming new groups and writing about suffrage.

The Colorado General Assembly passed another vote for women's suffrage in 1893. Suffrage groups in the state started with only $25 for their campaigns. NAWSA sent money and organizers. Journalist Minnie Reynolds convinced about 75% of newspapers in the state to support the effort. When the vote passed on November 7, 1893, Colorado became the second state to give women suffrage. It was the first state where men voted to give women the right to vote. After women gained equal suffrage, they ran for office and supported reforms. Colorado approved the 19th Amendment on December 15, 1919.

Idaho's Quick Approval

Idaho approved a change to its constitution in 1896, giving women the right to vote statewide. Idaho was one of the first states to do this.

Montana's First Woman in Congress

In Montana, men voted to end voting discrimination against women in 1914. After that, they elected the first woman to the United States Congress in 1916, Jeannette Rankin.

Oregon's Initiative for Suffrage

One after another, western states gave their women citizens the right to vote. The main opposition came from groups that sold alcohol and political machines. In Oregon, Abigail Scott Duniway (1834–1915) was a long-time leader. She supported the cause through speeches and her weekly newspaper The New Northwest. Women won the right to vote in 1912 using new ways to get laws passed directly by voters.

Utah's Unique Voting History

Mormonism in Utah made the fight for women's suffrage there special. In 1869, the Utah Territory, controlled by members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), gave women the right to vote. Seraph Young was the first woman to vote under a women's equal suffrage law in the U.S. (in a local election on February 14, 1869). However, in 1887, Congress took away Utah women's voting rights with the Edmunds–Tucker Act. This law was meant to weaken the Mormons politically. At the same time, some activists supported women's suffrage in Utah as a way to change certain practices. The LDS Church officially stopped supporting polygamy in 1890. In 1895, Utah adopted a constitution that gave women back the right to vote. Congress then allowed Utah to become a state with that constitution in 1896.

Washington's Long Struggle

In 1854, Washington was one of the first territories to try giving voting rights to women. The law was defeated by just one vote. In 1871, the Washington Women's Suffrage Association was formed, thanks to a campaign by Susan B. Anthony and Abigail Scott Duniway. In the late 1800s, laws passed by the Territorial Legislature were often overturned by the Territorial Supreme Court. This was because the suffrage movement and the alcohol industry (which was hurt by women's votes) fought over the issue. The first successful law passed in 1883 (overturned in 1887), and another in 1888 (overturned the same year). The movement then tried to get the right to vote through voter referendums in 1889 and 1898, but both failed. Finally, a change to the constitution gave women the right to vote in 1910.

Wyoming: The First State for Women's Votes

On December 10, 1869, Territorial Governor John Allen Campbell signed a law giving women the right to vote. This made Wyoming the first U.S. state or territory to grant suffrage to women. On September 6, 1870, Louisa Ann Swain of Laramie, Wyoming became the first woman to vote in a general election. In 1890, when Wyoming wanted to become a state, the U.S. Congress demanded that Wyoming take away women's voting rights. Wyoming's legislature famously replied, “We will remain out of the Union one hundred years rather than come in without the women.” Congress gave in. So, Wyoming became the 44th state and the first U.S. state where women could vote.

Northeast: A Hard-Fought Battle

Connecticut's Suffrage Journey

The women's suffrage movement in Connecticut began with Frances Ellen Burr, a writer who led a petition drive in the 1860s. She had attended the National Women's Rights Convention in Cleveland in 1853. Because of her efforts, a women's suffrage bill was introduced in the state House of Representatives in 1867, but it was defeated.

The Connecticut Woman Suffrage Association (CWSA) was formed in 1869. This meeting included important figures like Burr, Isabella Beecher Hooker, Catharine Beecher, and Harriet Beecher Stowe. Many famous activists spoke there, including Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony. Unlike other places, the local newspapers reported on the convention respectfully.

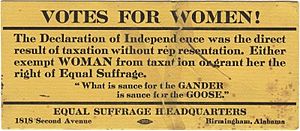

In the 1870s, sisters Julia and Abby Smith protested "no taxation without representation." They refused to pay local taxes because women couldn't vote on tax issues. The town took their property to pay the taxes.

The movement had some small wins. Married women gained the right to control their own property in 1877. Women could vote for school officials in 1893 and on library issues in 1909. However, progress was slow, and by 1906, the CWSA had only 50 members.

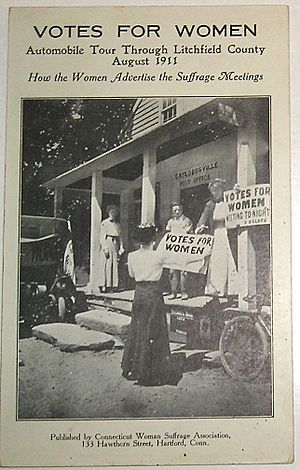

In 1909, as the women's suffrage movement grew nationwide, Katharine Martha Houghton Hepburn (mother of actress Katharine Hepburn) co-founded the Hartford Equal Suffrage League. In 1910, this group merged with the CWSA, and Hepburn became its president. With new energy, the CWSA organized an automobile tour in 1911, starting many new local groups. In 1914, they held the state's first suffrage parade with 2,000 people. By 1917, the organization had 32,000 members.

With Hepburn's support, a branch of the Congressional Union (later the National Woman's Party or NWP) formed in Connecticut in 1915. The NWP used more direct tactics. Fourteen Connecticut suffragists were arrested between 1917 and 1919 in Washington, D.C., for protesting outside the White House.

Connecticut's politicians resisted supporting the proposed Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. The state legislature finally met in a special session to consider the amendment. They approved it in September 1920, a month after it had already become law because enough other states had approved it. The CWSA then closed down in 1921.

Maine's Fight for the Vote

Women's suffrage work in Maine started in the mid-1850s. Important suffragists spoke in Maine, and in 1857, a women's rights lecture series began in Ellsworth. These lectures led to activism, with women sending petitions to the state legislature. By the late 1860s, the Snow sisters in Rockland started a women's suffrage club. In the 1870s, Margaret W. Campbell traveled Maine, speaking about women's suffrage. A convention was held in Augusta in 1873, forming the Maine Women's Suffrage Association (MWSA).

During the next few decades, MWSA continued to work for women's suffrage and partnered with NAWSA. Groups like the Maine Federation of Labor supported women's suffrage in 1906. In 1913, the Maine chapter of the College Equal Suffrage League formed, and the next year, the Men's Equal Rights League of Maine was organized. In 1915, Florence Brooks Whitehouse brought the Congressional Union to Maine.

By 1916, suffragists in Maine felt it was time to campaign strongly for a women's suffrage amendment. They held a suffrage school in January 1917. When the bill went to the state legislature, over 1,000 women watched. The bill passed and would go to a public vote in September 1917. Campaign offices were set up in Bangor. Suffragist Deborah Knox Livingston traveled over 200,000 miles campaigning. Despite all the hard work, voters rejected the amendment.

In February 1919, a law allowing women to vote for presidential electors passed the state. In November 1919, a special legislative session was called, and Maine approved the Nineteenth Amendment on November 5.

New Jersey's Early Voting Rights

New Jersey had a unique history. After the Revolutionary War, New Jersey's law allowed anyone with enough property to vote, including women. In 1790, the law specifically included women, and in 1797, election laws used "he or she" for voters. However, politicians later decided they didn't like women voting. In 1807, the law was changed to exclude women. When New Jersey wrote a new constitution in 1844, it limited voting rights to men. By 1947, all state rules against women voting were made useless by the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution in 1920. The 1947 constitution then included women as eligible voters again.

New York's Big Win

Suffragists knew that women's voting rights needed wide support. They hoped for universal suffrage, meaning everyone could vote. From April to November 1867, women campaigned hard in New York, giving out thousands of flyers and speaking in many places.

During the New York Constitutional Convention in 1867, Horace Greeley, who had supported women's suffrage for 20 years, surprisingly went against it. He supported voting rights for free Black men but not for women. New York lawmakers agreed with him.

Harriot Stanton Blatch, daughter of Elizabeth Cady Stanton, focused on New York. She got many working-class women involved and also worked with important society women. She organized street protests and worked behind the scenes to get support. New York finally approved women's suffrage in 1917.

Pennsylvania's Activist Roots

Pennsylvania was a hub for women's rights, home to activists like Lucretia Mott and the Grimké sisters. In 1854, the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society held one of the nation's first women's rights conventions. In 1869, Philadelphia hosted the state's first organized meeting of suffragists.

In 1871, Carrie S. Burnham tried to vote in a local election. When her ballot was rejected, she took her case to court, all the way to the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania, but she lost. She argued she had the right to vote because she was a "freeman" and a U.S. citizen.

To change the state constitution to include women's suffrage, a resolution had to pass two sessions of the state legislature and then be approved by voters. Groups started pushing for this in 1911, and it passed the legislature in 1913. The state's first suffrage march was held in Erie in 1913.

In 1915, as the state-level women's suffrage measure was on the ballot, Katharine Wentworth Ruschenberger and the Pennsylvania Woman Suffrage Association funded the creation of the Justice Bell. This bell was a copy of the Liberty Bell, but its clapper was tied so it couldn't ring until women won the right to vote. Jennie Bradley Roessing and Hannah J. Patterson drove the Justice Bell to campaign events in all 67 counties, but the vote was defeated in 1915.

Pennsylvania women did not get the right to vote until the federal amendment passed. The Pennsylvania legislature approved it on June 24, 1919, making Pennsylvania the 7th state to approve it.

Midwest: Progress and Setbacks

Illinois's Landmark Achievement

An early Illinois women's suffrage group was started by Susan Hoxie Richardson in 1855. Women in Illinois helped during the Civil War. Through her war work, Mary Livermore became convinced women needed to vote to make political changes. Livermore organized the first suffrage convention in the state in Chicago in 1869. In the 1870s, suffragists pushed for laws to allow women to vote. In 1891, a school suffrage bill passed. That same year, Ellen A. Martin found a loophole in the city charter of Lombard, Illinois, allowing her and other women to legally vote.

In the 1900s, Illinois suffragists continued to teach, raise awareness, and reach out across the state. By the 1910s, women had become very skilled in politics. Grace Wilbur Trout, a leader, organized car rallies and other public events. She made sure a local group was started in every Senate district.

The first Black suffrage group in the state, the Alpha Suffrage Club, was founded in 1913. Trout, other Illinois suffragists, and Ida B. Wells from the Alpha Suffrage Club, went to the Woman Suffrage Procession in March. Wells insisted on marching with the other suffragists, despite some trying to stop her.

In May 1913, a women's suffrage bill passed the state Senate. It then went to a vote in the House on June 11, 1913. The bill passed with six votes to spare. On June 26, 1913, Illinois Governor Edward F. Dunne signed the bill.

Women in Illinois could now vote for presidential electors and for all local offices not specifically named in the Illinois Constitution. Illinois became the first state east of the Mississippi River to give women the right to vote for president. It was important to show that women truly wanted to vote. Women's clubs, including the Alpha Suffrage Club, worked together to get women to vote. Over 200,000 women registered to vote in Chicago alone.

When the Nineteenth Amendment was being sent to states for approval, some states wanted to be the first to approve it. On June 10, 1919, Illinois became the first state east of the Mississippi to approve the amendment. It was the seventh state overall to approve it.

Kansas's Referendum Victories

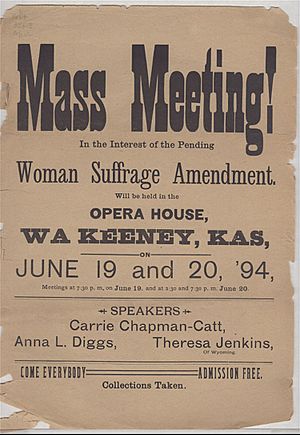

In March 1867, the Kansas legislature decided to include two public votes (referendums) in that year's November election. One would give voting rights to African Americans, and the other to women. The idea for the women's suffrage vote, the first in the U.S., came from state senator Sam Wood.

The American Equal Rights Association (AERA) strongly supported both votes. AERA, formed in 1866 by abolitionists and women's rights activists, wanted voting rights for both women and Black people. Lucy Stone and her husband Henry Blackwell started the AERA campaign in Kansas.

The AERA had hoped for help from the Kansas Republican Party. Instead, the Republicans decided to support voting rights only for Black men and formed a committee against women's suffrage. By the end of summer, the AERA campaign almost failed due to this opposition.

Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton caused controversy by accepting help from George Francis Train during the last two weeks of the campaign. Train was a wealthy businessman and speaker who supported women's rights, but he also spoke badly about African Americans. This upset many AERA members.

Women's suffrage was defeated in the November election. Voting rights for Black people were also defeated. The problems from this campaign in Kansas contributed to a growing split in the women's suffrage movement.

In 1887, women gained the right to vote in city elections. That year, in Argonia, Susanna Salter became the first woman mayor elected in the United States.

A vote for full suffrage was defeated in 1894. A third campaign in 1911-1912 gained even more support. Kansas had already banned saloons since 1880, which weakened the opposition to women's suffrage. The pro-suffrage side finally secured a women's suffrage amendment, and Kansas became the eighth state to allow full voting rights for women.

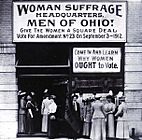

Ohio's Early Women's Rights Conventions

Women's suffrage work in Ohio began after the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention. Elizabeth Bisbee from Columbus was inspired to start a women's suffrage newspaper that year. The first Ohio Women's Rights Convention took place in Salem, Ohio in April 1850. It was the first women's rights conference outside of New York, and only women were allowed to speak or vote. One attendee, John Allen Campbell, later gave women equal voting rights in Wyoming.

At the 1851 convention in Akron, Ohio, thousands of signatures were collected for women's suffrage and delivered to the 1850 Ohio Constitutional Convention. However, both women and African-Americans continued to be denied voting rights. In 1869, the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA) was formed in Cleveland.

By 1894, women gained the right to vote in school board elections. Harriet Taylor Upton became president of the Ohio Woman Suffrage Association (OWSA) in 1899. She organized women across Ohio and doubled the number of activists. In 1903, NAWSA moved its national headquarters to Warren, Ohio.

In 1912, Ohio held another constitutional convention. A women's suffrage vote was passed during the convention. Activists campaigned heavily for and against it. Despite the hard work, the vote failed. After the loss, Ohio suffragists reorganized. Several new groups formed, and in 1914, they worked to get another women's suffrage vote on the ballot. Again, it failed.

After the 1914 defeat, Ohio suffragists focused on getting women the right to vote in city elections. On June 6, 1916, women in East Cleveland, Ohio won the right to vote in city elections. This was the first time women earned this right east of the Mississippi. In 1917, women in Lakewood, Ohio and Columbus, Ohio also won city voting rights. Ohio briefly gave women the right to vote for presidential electors in 1917, but it was later overturned. On June 16, 1919, Ohio approved the Nineteenth Amendment, becoming the fifth state to do so.

South Dakota's Path to Full Suffrage

Women in South Dakota shared a history with North Dakota until 1889. They gained the right to vote in school elections starting in 1887. Activists worked steadily over the years to build support for women's suffrage. However, they did not pass a full equal suffrage amendment until 1918. South Dakota approved the Nineteenth Amendment on December 4, 1919.

Wisconsin's School Voting Rights

Women's suffrage was discussed during the first state constitutional convention in Wisconsin in 1846. Early newspapers in Wisconsin supported women's suffrage. The first women's suffrage conference in Wisconsin was held in Janesville in 1867. Later, the Woman Suffrage Association of Wisconsin (WSAW) formed to lobby the state legislature, but their bills were unsuccessful. A new group, the Wisconsin Woman Suffrage Association (WWSA), was organized in 1869.

In 1884, a women's suffrage bill passed, allowing women to vote on school-related issues. This bill had to pass a second time in 1885 and then go to a public vote (referendum) in 1886, which it passed. However, the law was unclear, and there were problems when women first voted in 1887. Olympia Brown took the issue to court, and it went all the way to the Supreme Court of the United States. The court decided that women in Wisconsin could only vote on school-related issues if separate ballots and ballot boxes were created for them. This eventually happened, and women could vote for school-related issues again starting on April 1, 1902.

The Wisconsin legislature passed another women's suffrage vote in 1911. Multiple suffrage groups campaigned heavily for the vote on November 4, 1912. The efforts did not succeed, and the vote was defeated. Suffragists continued to educate and organize after the defeat. As the federal amendment was about to pass, Wisconsin tried to be the first state to approve it. Wisconsin approved the Nineteenth Amendment one hour after Illinois. However, Wisconsin was the first to deliver its approval paperwork to the State Department.

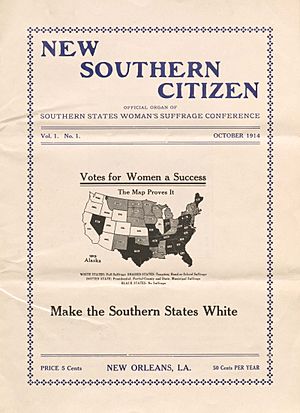

Southern States: A Different Approach

The story of suffragists in the South is often less known. Their work was shaped by the culture of their time. Many white and Black suffragists in the South were often educated women from wealthy families. Black women suffragists worked within their local clubs and later with the National Association of Colored Women's Clubs. Some also joined suffrage groups individually when their clubs were not allowed to join. Many Black women educators spoke out for voting rights for Black men and sometimes for Black women too. White middle-class women in the South who fought for voting rights were good at organizing.

In 1906, twelve representatives from Southern states met in Memphis to form the Southern Woman Suffrage Conference. Laura Clay was elected president. This group separated from NAWSA, choosing to focus on winning suffrage at the state and local levels rather than through a federal amendment.

Alabama's Long Road to Ratification

Early women's suffrage work in Alabama began in the 1860s with Priscilla Holmes Drake. Many women involved in the temperance movement also became involved with women's suffrage. In the 1890s, several women's suffrage groups formed, including the Alabama Woman Suffrage Organization (AWSO) in 1893. Emera Frances Griffin was a suffrage leader who spoke at the state constitutional convention in 1901. However, after 1901, there was a long break in suffrage efforts.

In the 1910s, several women's suffrage groups formed again, starting in Selma, Alabama with Mary Partridge. A Birmingham, Alabama suffrage league was started by Pattie Ruffner Jacobs in 1911. Another state group, the Alabama Equal Suffrage Association (AESA), formed and joined NAWSA. AESA held state conventions starting in 1913 and influenced some bills in the state legislature. In 1915, a women's suffrage bill was introduced but did not pass.

By 1917, suffragists in Alabama felt their best chance was to support the federal suffrage amendment. In June 1919, AESA started a campaign to support the Nineteenth Amendment. Suffragists from across the state came to Montgomery, Alabama to talk to lawmakers. However, the state legislature rejected the amendment in July and August. Alabama finally approved the Nineteenth Amendment on September 8, 1953.

Arkansas's Primary Election Victory

Early women's suffrage activism in Arkansas came from men. Miles Ledford Langley supported women's suffrage at the 1869 state constitutional convention. In 1881, Lizzie Dorman Fyler started a state women's suffrage club. The Woman's Chronicle, a newspaper edited by and for women, also started in 1888. Several women's suffrage laws were considered by the Arkansas General Assembly over the next few decades but did not pass.

In the 1910s, women's suffrage efforts gained speed. Socialist women like Freda Ameringer were involved. Several women's suffrage groups were created, including the Political Equality League (PEL) and the Arkansas Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). Suffragist Florence Brown Cotnam became the first woman to speak on the floor of the General Assembly in 1915. While that bill did not pass, Cotnam convinced the Governor to call a special legislative session in 1917. During this session, a bill passed that allowed women to vote in primary elections. Arkansas became the first state without full suffrage to pass a primary election law for women.

After this law passed, women worked to register voters and educate them. The first time women could vote was in May 1918 during the primary elections, and between 40,000 and 50,000 white women voted. African-American women were not allowed to vote in these primaries. Arkansas approved the Nineteenth Amendment on July 28, 1919, becoming the twelfth state to do so.

Delaware's Close Call

At a women's rights convention in 1869, the Delaware Suffrage Association was formed. Mary Ann Sorden Stuart spoke in both the U.S. Congress and the Delaware General Assembly in the 1870s and 1880s. In 1888, the Delaware WCTU started a "franchise department" to support women's suffrage. In 1895, the Delaware Equal Suffrage Association (DESA) formed. DESA educated people and talked to lawmakers. In 1897, the state held a constitutional convention, and activists from NAWSA came to help. While it was suggested that the word "male" not be added to the description of a legal voter, it did not pass. In 1900, Delaware did allow some women who paid property taxes to vote for school officials.

In 1913, one of the first suffrage parades in the state was held in Arden, Delaware. That year, Mabel Vernon of Wilmington, Delaware opened Congressional Union (later the National Woman's Party) headquarters in the state. Vernon helped create new ways to support women's suffrage in Delaware. Vernon and Florence Bayard Hilles were also more active protesters, part of the Silent Sentinels. One Sentinel, Annie Arniel from Delaware, spent 103 days in jail for protesting outside the White House.

A petition drive for a federal women's suffrage amendment started in Wilmington in May 1918. Suffrage headquarters were set up in Dover, Delaware in January 1919. Activists saw signs that the federal amendment would pass Congress. The General Assembly called a special session on March 22, 1920, to consider the federal amendment. Delaware could have been the 36th and last state needed to approve the Nineteenth Amendment. The whole country watched Delaware. Both suffragists and anti-suffragists campaigned heavily. However, a personal disagreement between a state representative and the governor turned the vote into a big fight. The General Assembly could not approve the amendment before the session ended on June 2. Delaware finally approved the Nineteenth Amendment on March 6, 1923.

Florida's City-Level Progress

Ella C. Chamberlain was a major force for women's suffrage in Florida between 1892 and 1897. She was in charge of a suffrage section in a Tampa, Florida newspaper and was president of the Florida Woman Suffrage Association. After Chamberlain left Florida in 1897, the suffrage movement slowed down until around 1912. That year, Jacksonville, Florida started the Equal Franchise League of Florida. In 1913, two women tried to vote in an election in Orlando, Florida, but were denied. In 1915, the city of Fellsmere, Florida allowed women to vote because of a technicality in its city rules. In 1918, several other cities also passed laws for women's voting rights in city elections. Florida did not approve the Nineteenth Amendment until May 13, 1969.

Georgia's Delayed Voting Rights

The first women's suffrage group in Georgia was organized by Helen Augusta Howard in the early 1890s. The group, the Georgia Woman Suffrage Association (GWSA), was against being taxed without having a say in government. Howard convinced NAWSA to hold their yearly meeting in Atlanta in 1895, the first time it was held outside of Washington, D.C. GWSA continued to fight for equal suffrage and other women's rights. Membership in GWSA grew in the 1910s. A Men's League for Woman Suffrage and a youth suffrage group formed in 1913.

In the following years, activists worked to pass women's suffrage laws in the state legislature, but they were unsuccessful. However, the city of Waycross, Georgia, passed a limited suffrage bill in 1917, allowing women to vote in city primary elections. In Atlanta, women won the right to vote in city elections in 1919. In July 1919, the Georgia Legislature considered the Nineteenth Amendment. On July 24, Georgia became the first state to reject the amendment. Even after the Nineteenth Amendment became law across the country, Georgia did not allow women to vote right away. Because of voter registration rules, women could not vote in the 1920 presidential election. The first time women voted statewide was in 1922. African-American and Native American women were still excluded from voting.

Kentucky's Early School Suffrage

In 1838, Kentucky passed the first statewide woman suffrage law (since New Jersey had removed theirs). This law allowed female heads of households to vote in elections about taxes and local school boards. Kentucky was important as a path to the South for women's rights activists. Lucy Stone visited Louisville in 1853, giving speeches to thousands.

After the Civil War, in 1867, the first suffrage association in the South was formed in Kentucky. Also, the first two suffrage associations in Madison County and Fayette County were started in the 1870s by Mary Barr Clay. In October 1881, the AWSA held its national meeting in Louisville, Kentucky, the first such meeting south of the Mason-Dixon line. At this meeting, the first statewide suffrage association in Kentucky was founded, and Laura Clay was elected president. In July 1887, Mary E. Britton spoke for woman suffrage at the Colored Teachers Association meeting in Danville, Kentucky.

When NAWSA formed in 1890, Laura Clay became a main voice for Southern white clubwomen. She led many campaigns across the South and West for NAWSA. In March 1894, the Kentucky General Assembly gave school voting rights to women in the cities of Lexington, Covington, and Newport. Also, Josephine Henry successfully lobbied for a state law about married women's property rights. In 1902, because of worries about Black women voting in Lexington, the Kentucky legislature took away this partial suffrage. The Kentucky Association of Colored Women's Clubs formed in 1903, and suffrage was part of their work. The Kentucky Federation of Women's Clubs (for white women only) also formed and worked to get school suffrage back, finally winning it in 1912 with a "literacy" test for women.

In 1912, Laura Clay stepped down as president of KERA. In 1913, Clay was elected to lead a new group, the Southern States Woman Suffrage Conference, which aimed to win the vote through state laws. Presidential voting rights for women in Kentucky were signed into law on March 29, 1920.

In January 1920, National Woman's Party members Dora Lewis and Mabel Vernon traveled to Kentucky. On January 6, Kentucky became the 23rd state to approve the 19th Amendment. On December 15, 1920, the Kentucky Equal Rights Association officially became the Kentucky League of Women Voters.

Maryland's Delayed Ratification

The 19th Amendment, which gives women the right to vote, was approved on August 18, 1920. However, Maryland did not approve the Amendment until March 29, 1941. Both the Maryland Senate and House of Delegates voted against women's suffrage in 1920. In the time between the U.S. and Maryland approving the amendment, women fought very hard for their rights.

Edith Houghton Hooker, born in New York in 1879, was a suffragist in Maryland. She was one of the first women accepted into the Johns Hopkins University Medical School. Hooker was an active member of the suffrage movement. She started the Just Government League of Maryland, which brought the question of women's suffrage to the people of Maryland. Hooker also founded the Maryland Suffrage News. This newspaper aimed to unite suffrage groups across the state and inform women about suffrage, since mainstream newspapers often ignored the movement.

Henrietta ("Etta") Haynie Maddox was the first woman to graduate from Baltimore Law School in 1901 and later become a lawyer in Maryland. At first, she wasn't allowed to take the exam because Maryland's law only permitted male citizens to practice law. So, Maddox and other female lawyers lobbied Maryland's General Assembly. In 1902, a bill passed, allowing women to practice law in Maryland. Maddox passed her exam and became the first licensed woman lawyer in Maryland in September 1902.

South Carolina's Late Start

Women's suffrage in South Carolina began as a movement in 1898, nearly 50 years after the women's suffrage movement started in Seneca Falls, New York. The state's women's suffrage movement was small, with little support from the state's legislature.

Virginia Durant Young was a key figure in South Carolina's women's suffrage movement. She was a temperance campaigner who also pushed for women's votes. She argued against claims that voting would take women into unpleasant situations, as polling places were often in bars. South Carolina's first women's suffrage movement was closely linked to the temperance movement led by the Women's Christian Temperance Union. Young and other suffragists formed the South Carolina Equal Rights Association (SCERA) in 1890.

In 1892, a state lawmaker, General Robert R. Hemphill, introduced an amendment for women's suffrage, but it was voted down. Over the 1890s, some laws were changed to give women more property rights. Virginia Durant Young died in 1906, and with her death, SCERA and other efforts for women's suffrage in the state ended.

Women's suffrage finally came to South Carolina through the Nineteenth Amendment after it passed Congress in 1919. South Carolina accepted the Nineteenth Amendment but also passed a law excluding women from jury duty. South Carolina finally approved the Nineteenth Amendment in 1969.

Tennessee's Decisive Vote

Woman suffrage entered public discussion in Tennessee in 1876 when Mrs. Napoleon Cromwell spoke to male delegates at the state Democratic convention in Nashville. She asked them to support women's suffrage, arguing that white women should vote since former male slaves could vote. The delegates applauded but also laughed. No resolution passed.

After the Women's Christian Temperance Union national convention in Nashville in 1887, a group of women in Memphis started the first woman suffrage league in the state in 1889. Lide Meriwether was elected president and became active in NAWSA. In 1895, Meriwether convinced Susan B. Anthony and Carrie Chapman Catt to come to Memphis. By 1897, there were ten new clubs in Tennessee. A state convention formed the Tennessee Equal Rights Association.

Due to the work by suffragists, in 1919, the Tennessee legislature passed an amendment to the state constitution granting women the right to vote only for presidential electors and in city elections. When the Susan B. Anthony amendment came to the Tennessee legislature, 35 other states had already approved it. There was some debate about whether the state could vote on a federal amendment if its legislature was in place before the amendment was submitted. The U.S. Supreme Court had to make a decision. Governor Roberts was also pressured by President Woodrow Wilson to call a special legislative session.

Finally, the legislature was called on August 7, 1920. Both pro- and anti-suffrage groups came to lobby. After several days of hearings, the Tennessee State Senate voted for approval on August 13. On August 17, the House committee urged approval. The House eventually approved it by a vote of 50 to 46. With Tennessee as the 36th state to approve it, the fight for the Nineteenth Amendment was over.

Texas's Primary Election Success

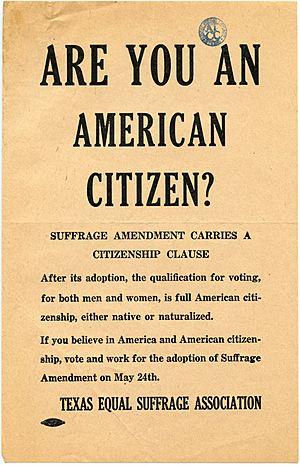

Women in Texas had no voting rights when Texas was a republic (1836-1846) or after it became a state in 1846. The idea of suffrage for Texas women was first brought up at the Constitutional Convention of 1868-1869, but it was rejected. The first suffrage group in Texas was the Texas Equal Rights Association (TERA), organized in Dallas in 1893.

Suffragists in Texas formed the Texas Woman Suffrage Association (TWSA) in 1903, later renamed the Texas Equal Suffrage Association (TESA) in 1916. Annette Finnigan was the first president. During her time, TWSA tried to organize women's suffrage groups in other Texas cities but found little support.

In April 1913, 100 Texas suffragists met in San Antonio and reorganized TWSA. Mary Eleanor Brackenridge became president, followed by Annette Finnigan in 1914, and Minnie Fisher Cunningham in 1915. By 1917, TESA had 98 local groups. In January 1916, 100 suffragists started the state branch of the National Woman's Party (NWP) in Houston.

Texas suffragists promoted their cause through lectures, pamphlets, newspapers, parades, and petitions to lawmakers. Many Texas suffragists used arguments about being native-born citizens to support women's suffrage. After the U.S. entered World War I, Texas suffragists also argued for the vote based on their war work and patriotism.

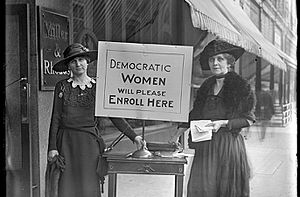

In 1915, Texas suffragists came within two votes in the Texas legislature of getting an amendment for women's voting rights in the state constitution. In March 1918, suffragists led the effort to get women the right to vote in state primary elections. In 17 days, TESA and other groups registered about 386,000 Texas women to vote in the Democratic primary election in July 1918. This was the first time women in Texas could vote. Texas suffragists then focused on getting their federal representatives to support the Susan B. Anthony amendment to the federal constitution. Both Texas senators and ten of eighteen U.S. representatives from Texas voted for the federal amendment on June 4, 1919. Later that month, Texas became the first state in the South and the ninth state in the United States to approve the 19th amendment.

Virginia's Fight for Equality

Women's suffrage in Virginia began in 1870 with the Virginia State Woman Suffrage Association, founded by Anna Whitehead Bodeker. Bodeker tried to get public support by writing newspaper articles and inviting famous suffragists to speak. However, after the Civil War, society emphasized traditional roles for women, and the association closed down in less than ten years. In 1893, Orra Gray Langhorne founded the Virginia Suffrage Society, but it also closed due to low membership.

In November 1909, about 20 activists from Richmond—including Lila Meade Valentine, Kate Waller Barrett, Adele Goodman Clark, Nora Houston, Kate Langley Bosher, Ellen Glasgow, and Mary Johnston—founded the Equal Suffrage League of Virginia. A few months later, it joined NAWSA. The league had about 100 members in its first year. By 1917, it had over 15,000 members, and by 1919, it had 32,000, making it the largest political group in Virginia.

The Equal Suffrage League of Virginia educated citizens and lawmakers by going door-to-door, giving out pamphlets, and sending members on speaking tours. The league also regularly asked Virginia's General Assembly to add a women's voting rights amendment to the state constitution in 1912, 1914, and 1916, but they were defeated each time. Virginia suffragists faced strong opposition from an anti-suffrage movement that used fears about race and traditional beliefs about women's roles.

When the United States Congress passed the Nineteenth Amendment in June 1919, Virginia suffragists lobbied for its approval, but Virginia's politicians refused. However, women of Virginia gained the right to vote in August 1920 when the Nineteenth Amendment became law after 36 states approved it.

Virginia did not officially approve the Nineteenth Amendment until 1952.

West Virginia's Tie-Breaking Vote

West Virginia shares many cultural norms with the rural South, including views on women's roles. As early as 1867, a state senator proposed a resolution for women's voting rights. But when the Southern Committee for NAWSA sought support in West Virginia, they found no women interested. Two NAWSA organizers came to the state in 1895 and helped organize local clubs and a state convention. The West Virginia Equal Suffrage Association (WVSEA) formed in Grafton, West Virginia in November 1895. In 1898, the Charleston Woman's Improvement League formed as part of the National Association of Colored Women, and suffrage was an important part of their work. The West Virginia WCTU did not officially support women's suffrage until 1900.

Several attempts in the legislature failed. In 1915, the legislature called for a statewide public vote (referendum) for woman suffrage. It was strongly defeated in almost all counties. When pro-suffrage Governor John J. Cornwell added the federal amendment to a special session of the legislature in February 1920, it was approved. Lenna Lowe Yost of Basnettville, West Virginia, president of WVSEA, organized petitions and a "living petition" of suffragists who greeted and lobbied lawmakers. On March 3, the House of Delegates voted for the amendment. However, the state Senate was tied. Senator Jesse Bloch returned from vacation just in time to break the tie. With a 15 to 14 vote in the Senate on March 10, the legislature sent the approval bill to the Governor. West Virginia became the 34th of the 36 states needed to approve the federal amendment for woman suffrage.

Former Territories Gain Voting Rights

Alaska's Path to Inclusion

White women in Alaska could vote in school board elections in 1904. Many white women's rights activists were involved with the WCTU. Cornelia Templeton Hatcher and Lena Morrow Lewis also campaigned for women's suffrage. Alaska's newspapers supported women's suffrage. Lawmakers in both the U.S. Congress and the Territorial legislature supported equal suffrage. On March 21, 1913, a law passed allowing white and Black women to vote, but it mostly excluded Alaska Natives. Because Alaska Natives were not generally considered U.S. citizens, they were not allowed to vote. In 1915, the Territorial Legislature passed a law allowing Alaska Natives to vote if they gave up their "tribal customs and traditions." Tillie Paul (Tlingit), who was arrested for helping Charlie Jones (Tlingit) vote, set a precedent that Alaska Natives could vote. In 1924, the Indian Citizenship Act made all Native Americans U.S. citizens. However, there was disagreement about whether Alaska Natives could now vote. In 1928, the Arizona Supreme Court ruled that Native Americans living on reservations could not vote. In 1948, the court changed that decision. Still, literacy tests continued to prevent Native Americans from voting. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 helped more Native Americans gain voting rights.

Hawaii's Fight for Self-Determination

During the rule of the Hawaiian Kingdom, women had different levels of political power, and some could vote. By 1850, voting was limited to male citizens. Before the Hawaiian Kingdom ended, efforts to support women's suffrage almost made Hawaii the first nation to give women the right to vote. The provisional government of Hawaii prevented women from voting. A suffrage committee of the WCTU tried to convince the Hawaii constitutional convention to allow women to vote. However, this was rejected because it would increase the number of Native Hawaiians eligible to vote.

Hawaii was taken over by the United States in July 1898. In 1899, members of NAWSA wrote the "Hawaiian Appeal" to the U.S. Congress, asking for women to have the same rights as men in the territory. Susan B. Anthony, one of the writers, partly wanted to ensure women could vote before Native Hawaiian men. In the end, voting rights were given to men who could read and write in English or Hawaiian. The territorial legislature was prevented from making laws about suffrage.

Emma Kaili Metcalf Beckley Nakuina and Wilhelmine Kekelaokalaninui Widemann Dowsett began to organize for women's suffrage. In 1912, Dowsett founded the National Women's Equal Suffrage Association of Hawai'i (WESAH). In 1915, Prince Jonah Kūhiō Kalanianaʻole, a delegate from the Territory, brought a bill to the U.S. Congress about women's suffrage. Hawaiian suffragists believed Congress would consider their bill, but it was ignored. He brought the bill again in 1916. Almira Hollander Pitman used her influence to speed up Congress's action. When Prince Kūhiō brought another bill to Congress in 1917, Pitman successfully pushed for its passage. This bill would allow the territorial legislature to make its own laws about women's suffrage. The bill passed and was signed in June 1918. In May 1919, suffragists pushed the territorial legislature to consider women's voting rights. They held rallies and were present during the votes, but efforts to pass a bill failed. After the Nineteenth Amendment was approved, the Secretary of State ruled that it applied to women in U.S. territories.

|

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |