Lila Meade Valentine facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Lila Meade Valentine

|

|

|---|---|

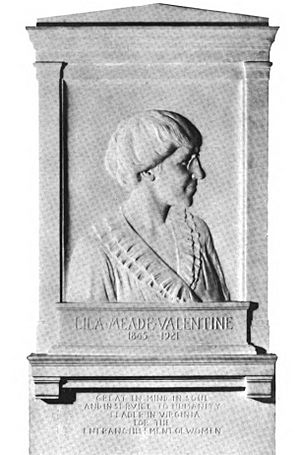

Portrait of Lila Meade Valentine, circa 1910

|

|

| Born | February 4, 1865 Richmond, Virginia, U.S.

|

| Died | July 14, 1921 (aged 56) Richmond, Virginia, U.S.

|

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | Education and health care reformer, suffragist |

| Spouse(s) | Benjamin Batchelder Valentine |

| Parent(s) | Richard Hardaway Meade and Jane Catherine "Kate" (Fontaine) Meade |

Lila Meade Valentine (born Lila Hardaway Meade; February 4, 1865 – July 14, 1921) was an important leader in Virginia. She worked to make schools better and to improve health care for everyone. She was also a key figure in the movement to get women the right to vote in the United States.

Lila helped start the Richmond Education Association to improve public schools. She also created the Instructive Visiting Nurses Association. Through this group, she helped get rid of a serious illness called tuberculosis in the Richmond area.

Valentine also co-founded the Equal Suffrage League of Virginia. She was its first president. Under her leadership, the league taught people and lawmakers about women's voting rights. They brought the issue to the state government three times between 1912 and 1916. Within 10 years, her group became the biggest political organization in Virginia.

When state efforts didn't work, Lila focused on a national change. She worked hard for the Nineteenth Amendment, which gave women the right to vote across the country. It became law shortly before she passed away.

Contents

Lila's Early Life and Marriage

Lila May Hardaway Meade was born in Richmond, Virginia, on February 4, 1865. She was the second of five children. Her father, Richard Hardaway Meade, co-founded a large pharmacy in Richmond.

Lila loved to read and spent many hours in her father's library. Her family was wealthy, so she received a good education for her time. However, she wanted to go to college, but most universities in Virginia did not accept women back then. She never earned a college degree.

On October 25, 1886, when she was 21, Lila married Benjamin Batchelder Valentine. He was a banker and writer from a well-known family. Benjamin, often called B.B., strongly supported Lila's work. He even hired tutors from the University of Virginia and the University of Richmond to help her learn more.

Lila was a bit rebellious for her time. She didn't use her husband's name, "Mrs. B.B. Valentine," when she wrote letters. This was unusual for women then.

Lila and B.B. had a child who was stillborn in 1888. They never had any other children. After the birth and a surgery, Lila's health was never fully strong again. She often had stomach problems and headaches for the rest of her life.

Working for Change

Improving Education

In 1892, the Valentines traveled to England. B.B. had business there, and they hoped the trip would help Lila's health. While in England, Lila was inspired by how women were helping to improve society. She returned to Richmond ready to fight for better education for everyone.

Richmond Education Association

Lila saw that Virginia's schools were not fair for everyone. So, in 1900, she worked with other activists like Mary-Cooke Branch Munford to start the Richmond Education Association (REA). They founded the group in Lila's home. The REA wanted to make public schools better. They also aimed to help poor children, African American children, and girls get a good education.

Lila was the REA president from 1900 to 1904. During this time, the group worked to:

- Improve training for teachers.

- Increase how much teachers were paid.

- Bring kindergarten and job training into city schools.

- Build public playgrounds.

In 1901, the REA started a Kindergarten Training School. They then asked Richmond's city council to create a kindergarten program in city schools. When the first kindergarten opened in 1903, it was named the Valentine Kindergarten in Lila's honor.

While leading the REA, Lila also helped replace Richmond's only high school. It was old, dirty, and full of rats. Lila spoke out about the bad conditions and invited reporters to see for themselves. Her efforts helped get $600,000 to build a new school, John Marshall High School, which opened in 1909.

Southern Education Board

In 1902, Lila went to a conference in Georgia for the Southern Education Board. This group worked to get more money and better standards for schools in the South. Lila was very excited by the conference. She convinced the Board to hold its next meeting in Richmond in 1903.

Lila wanted the 1903 meeting to talk about the education problems faced by poor white and African American students. She knew this topic might upset some Southerners. She held meetings to explain how the Southern Education Board could help Richmond.

Her hard work paid off. On April 22, 1903, the Southern Education Board met in Richmond. It was one of the first meetings in the city since the Civil War where white and Black people sat together. A newspaper article from that time said it was "a notable fact."

Cooperative Education Association

Lila's work made education reform more popular across Virginia. In 1904, she was asked to join a special committee. This committee, called the Cooperative Education Association of Virginia, worked to improve education standards across the state. Lila was the only woman on this important committee.

Continuing Her Education Advocacy

After joining the Cooperative Education Association, Lila spoke to many groups. She wanted to bring more attention to Virginia's education challenges. In her speeches, she asked for public money to improve school buildings, playgrounds, and job training for children.

In a 1904 speech, Lila said that everyone should help convince their neighbors that "it pays to educate the children of every class." She believed that Richmond could only become a great city if its schools trained children to be "efficient, productive, law-abiding, beauty-loving citizens."

Lila and Mary-Cooke Branch Munford also took part in the "May Campaign" of 1905. During this campaign, speakers traveled across the state. They gave over 300 speeches and helped start more than 50 local education groups, mostly led by women.

Health Care Reform

Lila's work in schools showed her that many children needed better health care. In 1902, she heard Sadie Heath Cabiness speak about her work with nurses. Sadie talked about teaching patients about hygiene and home care to help them get better.

Instructive Visiting Nurses Association

Inspired by Sadie, Lila gathered a group of women in her home. These meetings led to the founding of the Instructive Visiting Nurses Association (IVNA).

The IVNA helped people in Richmond with lower incomes get health care. In its first year, Lila convinced Richmond's city council to pay for a nurse at the City Home, a place for the poor. Before this, residents had to care for each other. In 1903, the IVNA also started sending nurses into Richmond's schools.

Fighting Tuberculosis

By 1904, Richmond faced a serious outbreak of tuberculosis. Lila was elected president of the IVNA to lead the fight against this disease. She worked with the Board of Health to open two tuberculosis clinics, one for white people and one for Black people. These clinics greatly reduced new cases of the disease.

Lila and Sadie Heath Cabiness then focused on people with tuberculosis who couldn't get into hospitals. They started the Anti-Tuberculosis Auxiliary, which led to the opening of Pine Camp Tuberculosis Hospital in 1910. At Pine Camp, patients received special treatment.

The IVNA's efforts to fight tuberculosis became a model for other health groups in Virginia. Lila encouraged the IVNA to offer its nurses to any town in Virginia that wanted to start its own branch.

Women's Right to Vote

Lila's busy schedule affected her health. She stepped down from her leadership roles with the REA and IVNA in 1904. In 1905, she and her husband moved to England. There, she learned about the movement for women's suffrage, or women's right to vote.

Being abroad helped Lila see problems in America more clearly. She saw that laws were not changing fast enough to fix issues like education, public health, and child labor. Lila realized that giving women the right to vote would help solve these problems.

Equal Suffrage League of Virginia

Early Days and Growing Numbers

In November 1909, Lila co-founded the Equal Suffrage League of Virginia. She was elected its first president. Other co-founders included artists Adele Goodman Clark and Nora Houston, doctor Kate Waller Barrett, and writers Ellen Glasgow, Kate Langley Bosher, and Mary Johnston. A few months later, the league joined forces with the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA).

At first, the Virginia suffragists faced public indifference. So, they changed their plan. They believed that teaching people about suffrage was the best way to make it a real political issue. The league began to educate citizens and lawmakers by:

- Going door-to-door.

- Giving out flyers.

- Setting up booths at fairs.

- Giving speeches.

- Holding street meetings in Richmond's Capitol Square.

In 1912, Lila met with important Richmond businessmen. She convinced them to start the Men's Equal Suffrage League of Virginia.

The Equal Suffrage League of Virginia grew quickly. It had nearly 120 members in its first year. By 1911, the league opened an office in Richmond, which became its state headquarters. By 1914, there were 45 local chapters. By 1915, there were 115. By 1919, the Equal Suffrage League of Virginia was the largest political organization in the state.

Virginia Suffrage News

In October 1914, the Equal Suffrage League of Virginia started its own monthly newspaper, Virginia Suffrage News. It helped members and supporters communicate across the state. As president, Lila wrote the first foreword. She wanted everyone in the suffrage movement to work together.

She wrote that the movement needed "good teamwork" and that everyone must "pull together with a right good will." She believed the newspaper would "bind us together in one harmonious whole."

Dealing with Race

Lila and the Equal Suffrage League privately believed that all women, regardless of race, should have the right to vote. However, in public, they did not openly support Black women's suffrage. They knew that most Virginians were against giving African American women the vote. They feared this would hurt their chances of getting any women the right to vote.

In 1916, the league even put out a flyer. It argued that giving white women the right to vote would help keep white people in power. It also said that literacy tests and poll taxes would stop Black people from voting.

Lila explained that not supporting African American women's suffrage publicly was a practical choice. She wrote to a friend: "I believe that all women, white or black, who meet the qualifications for suffrage in any State should have that right, but in working to secure that right, we should exercise common sense, and not complicate our efforts and add difficulties of the task by injecting elements of discord."

Lila as a Public Speaker

Lila preferred a "quiet, educational" way to gain support for suffrage. She didn't like extreme or aggressive methods. Public speaking was not easy for her at first. But she knew it was important. She developed a style that combined drama with clear language and facts. She won many people over with her charm.

Lila quickly became known as an engaging speaker. She spoke about women's suffrage whenever she could, often without a prepared speech. From 1912 to 1913, she gave over a hundred speeches across the state, including one to the Virginia House of Delegates. The National Woman Suffrage Association soon asked her to speak in other states too.

While many praised Lila, she also faced criticism. Some people who were once her friends would ignore her. When she spoke publicly, people sometimes yelled at her. During one speech, the crowd was even sprayed with pepper.

Changing Strategies for the Nineteenth Amendment

When Lila first joined the suffrage movement, she thought women would get the vote through changes to state laws. She even preferred a change to Virginia's constitution. In 1909, the Equal Suffrage League decided to ask the General Assembly to pass a state amendment in 1912.

On January 19, 1912, Lila and other Virginia suffragists spoke to Virginia's House of Delegates. The meeting lasted for hours. Even though people were impressed by Lila's speaking skills, the state legislature did not pass the amendment.

Virginia suffragists brought the issue of women's voting rights to the General Assembly in 1912, 1914, and 1916. But a women's suffrage amendment never passed in Virginia. After the failure in 1916, Lila and others decided to focus on a national change. By 1918, Lila supported the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. This new focus brought her more criticism from those who believed states should decide such matters.

After the United States Congress passed the Nineteenth Amendment, Lila and the Equal Suffrage League of Virginia fought for states to approve it. But the Virginia General Assembly refused to approve the Nineteenth Amendment. Virginia was one of nine southern states that would not give women the right to vote. Virginia's General Assembly did not approve the amendment until 1952. However, the Nineteenth Amendment became law in August 1920 after 36 states approved it.

Later Life, Death, and Legacy

On June 10, 1919, Lila's husband, B.B., passed away. He had suffered several heart attacks. Lila went to Maine with her sisters for a while. She found comfort in her suffrage work and a new interest in teaching women about how government works. She suggested a three-day conference on government for newly enfranchised women at the University of Virginia. It took place in April 1920. After that, she began working on a civics curriculum for Virginia's public schools.

Around this time, Lila's health, which was always delicate, got worse. By the time women gained the right to vote, she was very ill. Lila registered to vote from her bed, but she was too sick to go to the polls.

Lila Valentine died on July 14, 1921, at St. Luke's hospital. She was 56 years old and never got to cast a ballot.

Her memorial service was held at Monumental Episcopal Church, where she had been married 25 years earlier. The church was full. Women served as honorary pallbearers at her funeral. This was a first in Richmond's history.

Lila Valentine was buried at Hollywood Cemetery next to her husband, B.B.

In 1927, Adele Goodman Clark, a co-founder of the Equal Suffrage League, led a foundation to honor Lila. In 1936, a marble portrait of Lila by Harriet Whitney Frishmuth was placed in the Virginia State Capitol. Lila was the first woman to be honored there.

In 2000, the Library of Virginia honored Lila as part of the first group of Virginia Women in History.

Lila Valentine's name is also on the Wall of Honor at the Virginia Women's Monument in Capitol Square in Richmond.

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |